Abstract

Democratic backsliding in Central and Eastern European countries is on the rise. Independent judiciaries, other institutions of liberal democracy, as well as civil liberties and media freedom are being undermined, coupled with the human rights and dignity of certain groups being curtailed or even violated. In these difficult political and legal circumstances, non-state actors, such as interest groups, face many challenges. The goal of this research is to explore how interest groups in Poland perceive their position, what tactics they use in order to influence public policies and decision-makers, and whether they search for networking strategies in order to strengthen their position vis-à-vis the government. By placing our research in the Polish context, we fill the gap in the current literature on the situation of interest groups that face democratic backsliding. We base our analyses on new survey data collected from Polish interest groups in 2017–2018, conducted within the Comparative Interest Group Survey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scholars and practitioners are alarmed that democracy in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), especially in Hungary and Poland, is deteriorating (Bozoki 2015; Cianetti et al. 2018; Müller 2014; Herman 2016; Kelemen and Orenstein 2016; Sedelmeier 2014), despite being considered a democratic success story in the late 1990s (Linz and Stepan 1996; Ekiert and Kubik 1998). The wider context for our case study research is the process of democratic backslidingFootnote 1 that has been taking place in Poland since 2015 (Kotwas and Kubik 2019). It has been believed that democratic backsliding in CEE democracies weakens the role of civil society actors and their ability to influence the governing elites. One example of such vulnerable actors can be interest groups since they represent their constituents before government, afford people the opportunity to participate in the political process, lobby, educate the public about political issues, and some even monitor the activities taken by the decision-makers. Given these various tasks that interest groups undertake, we aim to answer the following question: Is there a difference between interest groups type in terms of the changes they face, organizational capacity and political activities in the context of democratic backsliding?

We believe that in order to understand the possible impact of democratic backsliding process on social actors, we need to explore more thoroughly not only political context, but also interest group representation systems, which includes the legal context, but also characteristics of various types of interest groups. Their condition serves as a litmus test for the quality of democratic processes, as they contribute to the quality, sustainability, and greater responsiveness of the democratic system (Lijphart 1984), but their condition also allows them to evaluate whether they are strong or have the capacity to mobilize if they have to face democratic breakdown in the future. Specifically, we explore how interest groups in Poland perceive their position and challenges, and what tactics they use in order to influence public policies and decision-makers. Following the findings in the literature on interest groups (Austen-Smith 1993; Baumgartner et al. 2009; Berry and Wilcox 2009; Binderkrantz 2008; Bouwen 2002; Dür and Mateo 2013; Hanegraaff et al. 2016; Klüver 2012; Mahoney 2007; Maloney et al. 1994), we believe that democratic backsliding might affect various types of interest groups differently. Therefore, we distinguish between sectional and cause groups, and we analyze their issues areas, funding and types of activities, as well as whether they use direct or indirect strategies to influence public policies, what type of institutions they approach at the national levels, as well as types of policy-relevant information they possess. Finally, we explore whether they coalesce with other organizations assuming that networking might strengthen them and allow them to survive democratic backsliding (Hanegraaff and Pritoni 2019).

We base our analysis on new survey data collected from Polish interest groups in 2017 conducted within the Comparative Interest Group (CIG) Survey initiative (Beyers et al. 2020; Kamiński and Rozbicka 2017). By giving a voice to the representatives of interest groups in Poland, which has not been done so far by researchers, we also hope to contribute to the still small number of studies of interest groups in Poland (Cianciara 2013; Jasiecki 2011; Kurczewska 2018; Kurczewska and Jasiecki 2017). Recognition of their peculiarities as well as understanding interest groups’ preferences and strategies in the public sphere in Poland may constitute an important point of reference for further and more extensive comparative analysis of interest groups in Central and Eastern European countries. However, because there are few studies on interest groups facing democratic backsliding, we hope to fill this gap with our study.

We find that the neocorporatist interest representation model in Poland, which governs political engagement of interest groups despite the existence of some pluralist elements, strengthens sectional groups. In 2017 we did not know the position of sectional groups, shaped by the neocorporatist system, was still, or maybe again, in a stronger position than cause groups regarding the influences on policymakers. However, the neocorporatist model is institutionalized and formalized and might be more difficult to destroy during the backsliding than the pluralist model, based on more loose and informal arrangements. The results from the survey show that sectional groups admit closer relations with the government, enjoy better direct contact with policymakers (i.e., politicians, such as ministers, deputies, or civil servants), whereas cause groups resort to more indirect strategies to influence government. Although it might be too early to capture the impact of democratic backsliding, in light of changing political and legislative standards in Poland, it might be expected that the developments might negatively affect cause groups since they rely on public funding, and do not closely cooperate with each other, which we assumed to be an important indicator of their survival.

We proceed as follows. First, we refer to the literature on democratic backsliding and demonstrate political and legal aspects regarding the functioning of interest groups in Poland, as well as to literature on interest groups to explain differences between sectional and cause groups, their characteristics and strategies used in their political activity, which we believe is crucial to distinguish in light of democratic backsliding. Next, we present data and methods, and in the empirical part, we analyze groups’ activities, priorities, and strategies in the public sphere and look for differences to see how prepared they are to face democratic backsliding challenges. In the concluding section, we suggest that future research should explore closely the ability of interest groups to survive in democratic backsliding conditions, as well as investigate how various cause groups might be constrained or embraced because of norms and ideology promoted by government during the democratic backsliding in Poland and elsewhere in the region.

Strength of interest groups and democracy backsliding

We theorize here how democratic backsliding might affect the political activities of interest groups and their strength in Poland by merging debates in the literature on political context, particularly “shrinking civic space” in Central and Eastern Europe, and in the literature on interest groups, especially on the institutional framework and differences in political activities between certain types of interest groups.

The important role of interest groups as advocates can be particularly significant when the future of democratic society, liberal institutions, and the rights and space that particular groups enjoy are at stake. Advocacy is considered as “the passionate plea for a particular position” (Zombetti 2006, 175) and the “the key mechanism by which citizens’ interests are expressed to the government” (Carothers 1997, 114). Serving as intermediaries between society and the state, interest groups can provide a voice for citizens’ views and make claims on governments and therefore can increase governments’ accountability and contribute to democratic quality.

The literature on interest groups suggests that associations and groups are potential prime mechanisms to ensure responsiveness of the political system to citizens’ demands (Berry and Wilcox 2009; Baumgartner et al. 2009). Their types vary from economic and trade associations to different kinds of identity and cause groups, such as groups representing particular social interests, (i.e. women or the elderly), or diffuse interests, (i.e. environment or ecology, leisure or religious groups). The most popular distinction is between economic and non-economic interest groups, as their area of focus, funding, as well as strategies and opportunities to influence decision-makers vary. Depending on the type of group, their role in political processes and scope of engagement in the public sphere differs. Overall, we can identify three functions of interest groups in the political system. The first one is to control the policymakers in terms of maintaining standards of legislative processes and democracy, such as transparency, consultation, and accountability (watchdog organizations). The second one is to support policymakers by providing them with specific expertise in a given area. The third function is to represent values, interests, and needs of certain social groups and advocate in this respect.

These functions mentioned above can be easily performed in democracies. Through legitimate and lawful institutions, democracy gives its citizens opportunities to control public policies recognizing that interest groups can contribute to the quality of democratic procedures and greater democratic accountability through civic participation, and more generally freedom of association and assembly (Diamond and Morlino 2004). Democratic backsliding, however, which takes place in old democracies as well as in new ones in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), is about curtailing certain civil liberties and freedoms of citizens. In CEE democratic backsliding is associated with illiberal forces pitching themselves against liberal forces and when incumbents legally access power and then gradually weaken democratic norms without abolishing key democratic institutions (Bustikova and Guasti 2017; Greskovits 2015; Guasti and Bustikova 2020; Foa and Mounk 2016; Kotwas and Kubik 2019). An important indicator of democratic backsliding, however, is a phenomenon that until recently dominated in authoritarian states: shrinking civic space. Shrinking civic space takes the following forms: control of resources, ideological regulations, legal restrictions, prosecution, and criminal law (Toepler et al. 2020; van der Borgh and Terwindt 2012; Buyse 2018).

Taking into consideration the above features of democratic backsliding, advocacy work in such countries can be either constrained or embraced by government attitudes and practices, and interest groups might be differently affected. Group type is an important determinant of organizations’ behavior and status (Binderkrantz 2008; Dür and Mateo 2013; Hanegraaff et al. 2016; Maloney et al. 1994). Given the characteristics of the cause groups, which are considered to be more like public interest groups campaigning for a specific cause or objective and often promoting approaches or issues that may not be of direct benefit to a specific group member, it might be anticipated that they would be more affected by democratic backsliding and subject to restrictions or manipulations from the illiberal governmental elites, who might be opposed to their advocacy. Sectional groups, however, aim to promote and protect interests of a specific section of society, with specific expertise in a given area, which is highly valued by policymakers (Bouwen 2002; Dür and Mateo 2013), and thus, their strength might be less affected by democratic backsliding.

Moreover, it has been pointed out that cause groups often struggle with financial sustainability, whereas sectional groups usually rely on their membership base and secure more stable funding. Finally, cause groups representing diffuse interests of the wider population often choose to refer to the broader public with the aim of changing public opinion, whereas sectional groups influence in a more direct way enjoying direct contacts with decision-makers (Baumgartner et al. 2009; Berry and Wilcox 2009). During backsliding, cause groups might be more likely to engage in indirect strategies especially if they advocate for a cause that might harm the governing illiberal elites. However, we might also expect that sectional groups tend to be in a better position to influence the decision-making process because of their expertise (Austen-Smith 1993; Mahoney 2007); they might resort not only to direct but also indirect strategies.

The strength of various interest groups and their opportunity for political activity depends also on the interest group regime (neocorporatist or pluralist) that dominates in a country once it starts to democratically backslide (Beyers et al. 2020). It is an important consideration because interest group representation is about the existence of the formal and informal mechanisms of inclusion of intermediary bodies, and the opportunity of interest groups to express and transmit citizens’ preferences and thus influence democratic decision-making. The neocorporatist model favors peak associations representing the interests of society and it offers some agreements and institutional arrangements between sectional groups and the government. In this model only major groups are involved in this special relationship with government, often enjoying direct contact. In the pluralist model of interest representation, which derives from a pluralistic model of democracy according to which many voices are expressed, listened to, and supported (Dahl 1998), there is no dominance of major groups but rather many groups exist and they compete with each other.

Often countries have elements of both pluralist and neocorporatist interest group representation, and it might be expected that in a country facing democratic backsliding the first one would be easier to dismantle and the second one has a greater chance to dominate. Since pluralism allows cause groups to flourish, the neocorporatist approach favors sectional groups. We use the example of Poland to demonstrate how democratic backsliding has already affected the regimes of interest groups and what we might expect in the future once liberal democracy erodes further.

Polish interest group representation system and new political context

Poland’s autocratic attempt to disable important defensive mechanisms, which is the separation of branches of power and the weakening to some extent of the autonomy of civil society, resulted in it being regarded as being halfway between a democracy and an authoritarian state (Magyar and Madlovics 2020).Footnote 2 The shrinking of civic space characterized by financial regulations, greater control, less government funding for liberal organizations (Bernhard 2020), negative campaigns against certain NGOs in local media (and then national media) further damaged their public image and might have affected their ability to implement the public advocacy activities of these groups. As a result, some civil society organizations in Poland were affected more than others after 2015, and these are organizations campaigning for minority and women’s rights, reproductive freedom, human rights, especially equal rights for LGBTQ + citizens (Grudzińska-Gross 2014; Grzebalska and Pető 2018; O’Dwyer 2018). At the same time there was greater support for organizations upholding conservative values (Ekiert 2019; Fomina and Kucharczyk 2016; Kotwas and Kubik 2019, 442; Płatek and Płucienniczak 2016).

Although the autonomy of civil society (media, entrepreneurs, NGOs, citizens) is not yet fully undermined, democratic backsliding can have a negative impact on interest groups in a more indirect way by weakening their representation system. The interest representation model is crucial to understanding interest groups’ engagement in the public sphere, as the institutional preconditions significantly impact the groups’ role in democracies and policymaking processes, as well as the strategies used. Because of the country’s past and influences during the transformation period combines elements of neocorporatism and pluralism. Some of these elements might be disrupted during democratic backsliding, yet others may be strengthened, constrained, or embraced.

The Polish interest representation model stems from corporatism, since under the communist regime interest groups, trade unions, and social organizations were subject to administrative restrictions and control by the Communist Party (Jasiecki 2002). When Poland began its transformation toward democracy and the market economy in the 1990s, approaches to civil society engagement had been influenced by history and the peculiarities of communism and the transition periods, defined by the underdevelopment of democratic institutions, the domination of trade unions and sectoral or industrial pressure groups, and the weakening of groups representing diffuse interests and watchdogs, as well as the politicization of lobbying (Jasiecki 2002, 124–126). The neocorporatist system led to the development of a strong institutionalized mechanism with certain types of interest groups (Jasiecki 2015), namely that regulations concerning “social dialogue” have been adopted, in other words the dialogue between the government and interest groups representing employers and employees (Act on the Social Dialogue Council, Ust. RDS 2015), and separate regulations governing the dialogue with public benefit organizationsFootnote 3 (Ust. d.o.p.p. 2003). Interest groups may in specific cases participate in the political and legislative processes within the formal social or civic dialogueFootnote 4 and may also participate in public consultations or public hearings in parallel. As the result of such developments, cause groups might perceive themselves as less integrated into the political process than sectional interest groups.

Simultaneously, the democracy promotion efforts of the USA as well as its support of civil society, the impact of the European Union and various programs directed toward non-state actors in Poland (Petrova 2014; Pospieszna 2014, 2019), and public administration made Poland lean toward the adoption of a more pluralist interest groups regime. Specifically, these influences led to the growth of civil society organizations, including many advocacy cause groups (Klon/Jawor Association 2019), as well as to pluralistic civil society engagement mechanisms, which are weak and non-institutionalized. Today the major pluralist element of interest group representation is featured in the new procedures concerning public consultations inspired by the EU.Footnote 5 Although consultations with interested non-state actors can be viewed as an important step toward the pluralistic model of interest representation, Polish consultation standards are relatively undeveloped compared to European ones, and the stakeholder dialogue in its “pluralistic” dimension continues to demonstrate considerable weaknesses (such as a narrow set of consultation tools, short time frames, problems related to openness and visibility, see, e.g., Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego 2008; Kwiatkowski et al. 2016; Obywatelskie Forum Legislacji 2019). Also rules on lobbying established in 2005 (Ust. lobb. 2005) have been widely criticized. One of their main drawbacks, in the context of this research, is that they do not concern interest groups but only individual lobbyists, who are obliged to register. This law was supposed to be changed several times, the most recent attempt in 2017, but without success since the last proposal has been frozen at the preparatory phase.

The ability of interest groups to influence decision-makers is further jeopardized by the current political situation. After parliamentary elections in 2015, deficits in applying consultation procedures have been observed, which demonstrate two points. First, there is a tendency to limit the time for consultations or to omit consultations by applying a separate legislative regime without proper justification. Second, there is a tendency to overcome this obligation by issuing proposals by public organs other than the government (such as the Sejm or Senat) because in such cases there are no rules imposing duties in relation to conducting public consultations (Obywatelskie Forum Legislacji 2019). Moreover, there are attempts to take advantage of scandals to discredit civil society organizations, curtail their financial resources, and silence the civic sector by introducing legislation to limit the space available for its activities mentioned above. These all might turn interest groups’ behavior into “wild” lobbying, because of personal and professional connections that sectional groups have, as well as procedural and administrative weaknesses, or “ad hoc” lobbying, namely spontaneous, “one-case” actions.

The legal and political context regarding the interest representation model in Poland is not favorable. Given the fact that current democratic backsliding (disadvantages of legislative practice, deterioration of consultation standards and transparency) makes it difficult for all interest groups to operate, regardless of type, however, it can be expected that the impact will vary depending on the interest groups’ type of engagement in the public sphere. We anticipate that cause groups in Poland are more financially vulnerable, rely more on indirect lobbying, and also might search for cooperation with parallel organizations to strengthen their advocacy. On the contrary, sectional groups, are well-endowed with information linked to a particular policy area, enjoy more direct access to policymakers, rely more on direct strategies, but might also consider indirect strategy as a last resort, especially when facing democratic backsliding. Finally, given the weakness of cause groups, it might be expected they will be interested in building and joining networks as a strategy that might strengthen the mission of advocacy (Hanegraaff and Pritoni 2019).

Challenges perceived and strategies used in political activity of Polish interest groups

Data and methods

In our study we give a voice to the representatives of interest groups in Poland to express their opinions and for the purpose of this study, we have used a survey conducted among Polish organizations within the CIG initiative (Beyers et al. 2016). The CIG initiative focused on groups at the national level. Thus, groups at regional and local levels were eliminated from the sample. The same went for law firms, consultancy firms, and all types of private companies. All in all, 1129 interest groups in Poland (Rozbicka et al. 2019) met the CIG criteria, and therefore have been considered for this study.

We achieved a survey response rate of 25–30%. This rate of responsiveness should not be considered as low due to the fact that lobbying and advocacy are still considered as highly sensitive topics in Poland and have strong negative connotations, often identified as unethical activities, gray areas, or political corruption. Despite our repeated invitations sent via regular post, email, and phone calls, a significant number of respondents presented a negative attitude in relation to their participation in the survey and were reluctant to reveal information concerning their organizations. For these reasons the number of replies should be considered as relevant and representative for the interest groups sector in Poland.

In order to conduct an analysis, we placed business and professional groups with economic interests into the category of “sectional groups,”Footnote 6 and identity groups, leisure groups, and groups representing diffuse interests (including human rights pressure groups and watchdogs) into a second category of “cause groups.” Our sample contains 175 cause groups and 119 sectional organizations.

Empirical analysis

Given the threats resulting from democratic backsliding in the future, first we analyze survey questions on interest groups’ perception regarding political challenges, then the profile of sectional and cause groups—their issue areas, funding and type of activities—as well as strategies they use to influence public policies, what type of institutions they approach at the national levels, the types of policy-relevant information they possess. Finally, we explore whether they coalesce and network with other organizations.

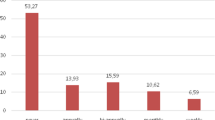

We found differences here between the two categories of group regarding their perception of political challenges (Fig. 1). Namely, sectional groups were more concerned by the euro currency crisis, the complexity of decision-making procedures, the impact of the 2008 financial crisis, EU citizens’ access to the labor market, and the competitiveness of companies, as compared to cause groups. In turn, cause groups considered moral and ethical issues discussed in the public sphere in Poland as a challenge, whereas the complexity of the decision-making procedures, and the distance between individual citizens and policymakers did not seem to be a major obstacle for them. Given these results, we may suggest that in 2017 interest groups did not perceive the decline of democratic standards as a major concern.

Source: Own calculations based on IGPOL data (Rozbicka, Kamiński, Pospieszna 2019). Survey question: How important are the following political challenges for your organization? The responses ranged from 1—“Not at all important” to 5—"Very important.” The figure contains percentage of respondents who answered 1 and 2 were coded as “Not important,” 4 and 5 as “Important”

Challenges for Polish Interest Groups, 2017–2018.

Generally speaking, both groups seem to be somewhat uninterested in direct engagement in political affairs. Nevertheless, we do observe differences between groups regarding the activities taken up by them. Sectional groups are more likely than cause ones to engage in advocacy or lobbying, whereas cause groups, rather than sectional ones, engage in fundraising, promoting volunteering, as well as in the monitoring of election campaigns (Table 1). We find that if cause groups choose to engage in advocacy or lobbying they do so mainly at local and subnational levels, whereas sectional groups are more often engaged in advocacy and lobbying at national, European, and international levels.

Interestingly, 74% of all interest groups in our sample take the form of associations, as they have a membership structure. This finding has strong implications in terms of their engagement in the public sphere due to the fact that membership fees, subscriptions, or fundraising contributions constitute a very important source of income for associations (60% of groups’ budgets). Business and professional associations usually enjoy steady financial support from their members, as they usually work on issues directly related to the wellbeing of their members. However, the membership subscriptions, regardless of the type of organization, do not seem to be the only source. Another important source of income comes from private donations and national and local government funding, which matters especially for cause groups. In fact, overreliance on state funding, and distribution via commune-level open calls, makes cause groups financially vulnerable and dependent, which confirms our assumption in this respect.

Next, we analyze the differences between two types of interest groups in terms of the organizational capacity and political activities they take in the context of democratic backsliding, using t test statistical procedure in order to determine difference between the means (Table 2). The survey asked about specific types of strategies used to affect or influence public policies and the frequency of undertaking such actions. In general, the most popular activities were those that included publication of reports and brochures as well as statements or position papers on the website. Second, organizations also tended to engage with media through debates, interviews, and correspondence with the aim of increasing media attention. The third (most popular) strategy concerned organizing conferences of experts and other stakeholders. These types of activities occurred at least once during a 12-month period (in some cases even more frequently such as monthly or quarterly). Interest groups seem to be less interested in participating in letter-writing campaigns, or signing petitions directed at public officials. The strategies that they avoid are those that involve strikes, boycotts, or demonstrations. (84% of respondents indicated that they did not do this during the last 12 months.) They also do not engage in electoral campaigns (90%).

Sectional groups generally demonstrate greater activity and are more likely than cause groups to use both direct and indirect strategies to achieve their goals. However, when asked about the time they need to devote when using specific tactics, sectional groups require more time to engage in indirect than in direct activities, as compared to cause groups. This finding may imply that cause groups in Poland are more experienced in conducting indirect strategies and thus need less time to engage in tactics of this type than sectional groups. It might also imply that indirect lobbying plays a crucial role for those groups to achieve their goals, on the one hand, and also to be noticed by the public and obtain scarce resources from potential new supporters, on the other.

The health of the pluralist interest representation system shows the engagement of interest groups in consultations. When asked whether and how often an organization responded to open consultations run by the government during the last 12 months, 32% participated in consultations at least once every 12 months, and another 18% at least once every 3 months. Undeniably, cause groups respond less often to open consultations by the government and serve less time on advisory commissions or boards. The elements of the neocorporatist interest representation system in Poland seem to make sectional groups bolder in direct contacts with policymakers, which is in line with our assumption. Such an interaction between sectional actors and policymakers is even more likely to be initiated by the groups rather than policymakers.

Our findings further indicate that cause groups in Poland seem to be less integrated into the political process than sectional ones, since integration of sectional groups seems to be institutionalized in the partnership and frequent direct contacts with decision-makers (Table 3). Sectional groups indicated that they actively sought access (at least once every 3 months, or even once a month during the last 12 months) to ministers, including their assistants/cabinets/political appointees (political level), as well as to civil servants working in departmental ministries, such as agriculture, environment, transport and health. The least contacted institutions at the national level by both type of groups were the courts (77% of respondents indicated no contact), national civil servants working for the coordination of EU affairs (67% respondents indicated no contact), and national civil servants working in the Prime Minister’s Office (65%) (see Table 3). Respondents were also asked about contacts with political parties. In general, both types of organizations did not seek access to members or officials affiliated with certain political parties. If there was a contact, it was on average only once during the past 12 months, and only with the two dominating parties in the political arena in Poland in 2017 (Law and Justice and Civic Platform). Being less integrated into the political process, the cause groups need to rely on indirect lobbying strategies.

Our data confirmed that sectional groups, in general, are well-endowed with technical, scientific, legal, and/or economic knowledge of their sector (see, e.g., Bouwen 2002; Dür and Mateo 2013). Information possessed by sectional groups that is linked to particular policy areas is a resource that might be highly valued by policymakers. Cause groups, however, do not present research or technical information to policymakers. This finding proves that cause groups are, in a way, in a weaker position as compared to sectional ones, as they often deal with general issues that are not necessarily anchored to any sector or branch. It also explains that sectional organizations are more interested in direct contacts, as it serves to transfer specific expertise to policymakers at the national level. Owing to the fact that cause groups often lack direct access to policymakers (which sectional groups enjoy) and also have less specific expertise, they are more likely reach for indirect tactics to put pressure on policymakers (Table 4).

We also analyzed data on coalition formation and networking abroad, which might be a strategy helping them to strengthen their position and to survive. In this respect, we found that the majority of Polish interest groups (60%) do not belong to any European or international umbrella organization or network. However, among those that form coalitions, sectional groups are more often members of European or international organizations than cause ones. Polish sectional groups support umbrella organizations mainly by paying the membership subscription and providing policy information or expertise, and in this respect 50% of respondents consider their role as “somewhat influential” and “very influential.” Also, Polish groups do not need membership or coalitions with foreign organizations to enhance their position in Poland and put pressure on domestic institutions. However, the representatives of sectional groups are of the opinion that foreign organizations inform them about key European and international political developments, provide expertise and information, as well as help to connect with other like-minded interests outside Poland, but are less helpful in providing judicial advice or access to government agencies (Table 5).

Both groups do not consider long-term cooperation in Poland as well as ad hoc coalition formation with like-minded domestic organizations as a vital strategy (overall 28% of all indicated activities) but differ in regards to specific areas of cooperation (Table 6). The most frequent forms of cooperation for sectional groups are joint statements (such as joint press statements or position papers) and to represent other stakeholders in committees, advisory bodies, or meetings with representatives of the government. Cause groups, however, were more likely to cooperate in the area of fundraising and sharing staff and personnel. This means that building and joining networks pays off as it provides access to some resources; however, despite cooperation there is still a lot of competition between cause groups.

Whereas competition is a challenge for both types of groups, cause groups consider it as a greater obstacle to their survival, as compared to sectional groups, which can even network with groups that have conflicting interests. Strong competition for cause groups may be a result of the plethora of similar like-minded groups with which they have to compete for members, donations, and subsidies. This can be confirmed by responses to another question in the survey—about challenges for the maintenance of the organization—cause groups indeed recognize competition as a more challenging factor than sectional groups (47% of respondents from the cause groups found it important and very important) and consider competition with similar organizations as an impediment.

Conclusion and discussion

Whereas interest groups play a significant role in the public sphere—from the viewpoint of the accountability and transparency of political processes, as well as of revealing legitimacy of political institutions being representatives of citizens’ interests—the situation of democratic backsliding makes discussion about their role in democracy even more important. Polish interest groups, already well-established since the transition process, currently face new challenges because of democratic backsliding. The data compiled within the CIG initiative allowed us to focus on Polish interest groups operating in difficult times of backsliding that began with the new populist right-wing government taking power in 2015.

In relation to the specificities of Polish interest groups operating at the national level, we found that most of them have a membership structure. However, their source of finance differs. For instance, cause groups’ source of funding is more likely to come from contributions from charities, corporate sponsors, and especially from the national government, than business groups. The dependence on government funding, makes these groups more vulnerable than sectional ones, which confirms our assumption. Next, we have found that business groups are in a stronger position than cause groups in the sense that they do enjoy direct contact with decision-makers and perceive themselves to possess the expertise that is desired by the decision-makers. Although Poland has elements of pluralism and neocorporatism, our findings show that neocorporatism dominates, and we do not know if 2 years of democratic backsliding could have moved Poland in this direction.

Neocorporatist tradition in Poland is strong enough to make sectional groups more integrated into political processes than cause ones. While cause groups, in order to fulfill goals, are more likely to go public with their activities, business groups are preoccupied with gaining access (to influence public policies and policymakers) through advocacy and lobbying as well as being more involved in the consultation processes. These findings also confirm this general tendency described in the literature (Dür and Mateo 2013). Given these findings, we can expect that democratic backsliding will further strengthen the neocorporatist model and weaken the pluralist one—sectional groups will continue enjoying direct contacts with policymaking; cause groups will have to continue relying on shaping and mobilizing public opinion in order to put pressure on policymakers (in fact, they might have no other option but to resort to indirect strategies in order to put pressure on policymakers). Moreover, cause groups, because they are more likely to rely on public finances might be more vulnerable and subject to manipulation. In turn, business and professional associations enjoying steady financial support from their members and working on issues directly related to the wellbeing of their members, might feel less vulnerable.

As the results of such developments, advocacy groups might not shrink in numbers but plurality might be further diminished. The decreasing transparency and standards of legislative processes might further weaken the efficacy of direct lobbying performed via institutional mechanisms (such as consultations). Therefore, it might hamper further mechanisms of the inclusion of intermediary bodies and their opportunity to express and transmit citizens’ preferences and thus influence democratic decision-making. In this respect the role of certain cause groups might be further undermined. For many cause groups the civic space will shrink, but for the others it will change as they will engage into the provision of services. Thus, further research should embark on investigating the ability of cause groups to survive and to investigate which groups were constrained (e.g., liberal cause groups) and which were embraced (e.g., conservative groups) by the changing political regime.

Finally, we included in our research an important indicator of the strength of interest groups in backsliding times, which is the ability to coalesce and search for networking strategies in order to strengthen their position vis-à-vis the government. Contrary to our expectations we found the willingness of cause groups to coalesce somewhat feeble. Although they do recognize building and joining networks as a strategy that pays off in order to get access to information, support, or joined projects, there is more group competition than cooperation. Similar organizations, in terms of their ideology or cause, may find competition a challenge for cooperation, as they need to compete for members, funding, and support. Therefore, in a crowded environment, organizations may avoid alliances with other groups in order to enhance their own reputations and to distinguish themselves from other organizations representing similar interests. However, we believe that it might be too early for them to see the merits of coalescing and networking as the research was conducted at the beginning of democratic backsliding; this can be the next step. To conclude, these and other findings open other avenues of research on interest groups in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in the comparative perspective and in the current situation of democratic backsliding and tumult which further weakened interest groups and made them vulnerable vis-à-vis the government.

Notes

The decline of democratic regime attributes among countries that underwent successful democratization and were engaged in democracy promotion can be observed. Scholars tend to term “democratic setbacks,” “democratic rollback,” “democratic recession” or “democratic erosion” to denote autocratization processes taking place within democracies (Lührmann and Lindberg 2019).

According to the Freedom House “Nations in Transit 2020” report, Poland is categorized as a semi-consolidated democracy. V-Dem Democracy Report 2020 report the erosion of democratic norms in 26 countries, Poland was among the illiberal countries where liberal democratic institutions and norms are weakening.

“Public benefit organizations” are non-governmental organizations (such as associations or foundations) as well as non-profit companies that have a special legal status as such decreed by a court.

According to these provisions, when new policy positions are proposed in particular sectors or issues, there should be a 30-day consultation period with respective interest groups.

The consultation procedures concern written public consultations that are run at the stage of legislative works undertaken at governmental level (by ministries). They were introduced into the Statue of the Work of the Council of Ministers in 2013 as a result of a governmental “Better Regulations Program 2015.” The program was initiated after the turmoil of the ACTA (Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement) (Dür and Mateo 2014; Meyer and Vetulani-Cęgiel 2017), where strong lobbying against this agreement resulted in mass demonstrations in Poland and all over the Europe and initiated a large public debate covering, among others, the issue of transparency of legislative processes. The program was inspired by European-level works on the EU Better Regulation Initiative (European Commission 2015), and the goal was, inter alia, to improve the consultation processes and to increase the opportunity for interest groups to be treated as an important voice in the policymaking process. According to these procedures, proposed legislation can be consulted publicly for a minimum of 21 days. (This term is shorter for proposed regulations, proposed assumptions to legal acts, or separate regimes in relation to legislation under the condition of special justification.)

It should be noted that trade unions are excluded from the category of sectional groups. Trade unions are sectional groups that are powerful advocates for policies that predominately benefit very narrowly defined members. If we choose to include them, the difference between sectional groups and cause groups will be inflated, which would not give us any explanatory power, because the results could have been driven by trade unions. We wanted to have a relatively equal size of both sectional and cause groups in order to compare them.

References

Austen-Smith, D. 1993. Information and Influence: Lobbying for Agendas and Votes. American Journal of Political Science 37(3): 799–833.

Baumgartner, F.R., J.M. Berry, M. Hojnacki, B.L. Leech, and D.C. Kimball. 2009. Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why. University of Chicago Press.

Bernhard, M. 2020. What Do We Know About Civil Society and Regime Change Thirty Years After 1989? East European Politics Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2020.1787160.

Berry, J.M., and C. Wilcox. 2009. The Interest Group Society, 5th ed. New York: Pearson.

Beyers, J., D. Fink-Hafner, W. A. Maloney, M.Novak, and F. Heylen. 2020. The Comparative Interest Group-survey Project: Design, Practical Lessons, and Data Sets. Interest Groups & Advocacy 9: 272–289.

Binderkrantz, A. 2008. Different Groups, Different Strategies: How Interest Groups Pursue Their Political Ambitions. Scandinavian Political Studies 31(2): 173–200.

Bouwen, P. 2002. Corporate Lobbying in the European Union: The Logic of Access. Journal of European Public Policy 9(3): 365–390.

Bozoki, A. 2015. Broken Democracy, Predatory State, and Nationalist Populism. In The Hungarian Patient: Social Opposition to an Illiberal Democracy, ed. Péter, Krasztev, and Jon Van Til. Budapest: CEU Press.

Bustikova, L., and P. Guasti. 2017. The Illiberal Turn or Swerve in Central Europe? Politics and Governance 5(4): 166–176.

Buyse, A. 2018. Squeezing Civic Space: Restrictions on Civil Society Organizations and the Linkages with Human Rights. The International Journal of Human Rights 22(8): 966–988.

Carothers, T. 1997. Democracy Assistance: The Question of Strategy. Democratization 4(3): 109–132.

Cianciara, A.K. 2013. Polish Business Lobbying in the EU 2004–2009: Examining the Patterns of Influence. Perspectives on European Politics and Society 14(1): 63–79.

Cianetti, L., J. Dawson, and S. Hanley. 2018. Rethinking “Democratic Backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe—Looking Beyond Hungary and Poland. East European Politics 34(3): 243–256.

Dahl, R.A. 1998. On Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Diamond, L., and L. Morlino. 2004. The Quality of Democracy: An Overview. Journal of Democracy 15(4): 20–31.

Dür, A., and G. Mateo. 2013. Gaining Access or Going Public? Interest Group Strategies in Five European Countries. European Journal of Political Research 52(5): 660–686.

Dür, A., and G. Mateo. 2014. Public Opinion and Interest Group Influence: How Citizen Groups Derailed the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement. Journal of European Public Policy 21(8): 1199–1217.

Ekiert, G. 2019. The Dark Side of Civil Society. Concilium Civitas. www.conciliumcivitas.pl/en/almanac/item/97-the-dark-side-of-civil-society. Accessed 30 Aug 30 2019.

Ekiert, G., and J. Kubik. 1998. Contentious Politics in New Democracies: East Germany, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, 1989–93. World Politics 50(4): 547–581.

Foa, R.S., and Y. Mounk. 2016. The Danger of Deconsolidation: The Democratic Disconnect. Journal of Democracy 27(3): 5–17.

Fomina, J., and J. Kucharczyk. 2016. The Specter Haunting Europe: Populism and Protest in Poland. Journal of Democracy 27(4): 58–68.

Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego. 2008. Przejrzystość procesu stanowienia prawa. Raport z realizacji projektu “Społeczny monitoring procesu stanowienia prawa.” Warsaw: Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego.

Greskovits, B. 2015. The Hollowing and Backsliding of Democracy in East Central Europe. Global Policy 6: 28–37.

Grudzińska-Gross, I. 2014. The Backsliding. East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 28(4): 664–668.

Grzebalska, W., and A. Pető. 2018. The Gendered Modus Operandi of the Illiberal Transformation in Hungary and Poland. Women’s Studies International Forum 8: 164–172.

Guasti, P., and L. Bustikova. 2020. In Europe’s Closet: The Rights of Sexual Minorities in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. East European Politics 36(2): 226–246.

European Commission. 2015. Better Regulation Guidelines, Commission Staff Working Document, Strasbourg, 19.5.2015, SWD(2015) 111 final, COM(2015) 215 final SWD(2015) 110 final.

Hanegraaff, M., and A. Pritoni. 2019. United in Fear: Interest Group Coalition Formation as a Weapon of the Weak?”. European Union Politics 20(2): 198–218.

Hanegraaff, M., J. Beyers, and I. De Bruycker. 2016. Balancing Inside and Outside Lobbying: The Political Strategies of Lobbyists at Global Diplomatic Conferences. European Journal of Political Research 55(3): 568–588.

Herman, L.E. 2016. Re-evaluating the Post-Communist Success Story: Party Elite Loyalty, Citizen Mobilization and the Erosion of Hungarian Democracy. European Political Science Review 8(2): 251–284.

Jasiecki, K. 2002. Lobbing w USA, Europie Zachodniej i Polsce: Podobieństwa i różnice. Studia Europejskie 4: 117–134.

Jasiecki, K., ed. 2011. Grupy interesu i lobbing: Polskie doświadczenia w unijnym kontekście. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Filozofii i Socjologii PAN.

Jasiecki, K. 2015. Problemy partycypacji społecznej w Polsce i ich wpływ na politykę publiczną. Studia z Polityki Publicznej 3(7): 101–119.

Kamiński, P., and P. Rozbicka. 2017. Ogólnopolska ankieta odnośnie organizacji pozarządowych i grup biznesu. Birmingham and Krakow: Aston University i Uniwersytet Jagielloński.

Kelemen, R.D. and Orenstein, M.A. 2016. Europe’s Autocracy Problem: Polish Democracy's Final Days. Foreign Affairs, January 7. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/poland/2016-01-07/europes-autocracy-problem

Klon/Jawor Association. 2019. The Capacity of NGOs in Poland 2018—Key Facts. Warsaw: Klon/Jawor Association. Retrieved from https://api.ngo.pl/media/get/110579

Klüver, H. 2012. Biasing Politics? Interest Group Participation in EU Policy-Making. West European Politics 35(5): 1114–1133.

Kotwas, M., and J. Kubik. 2019. Symbolic Thickening of Public Culture and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism in Poland. East European Politics and Societies: and Cultures 33(2): 435–471.

Kurczewska, U., and K. Jasiecki, eds. 2017. Reprezentacja interesów gospodarczych i społecznych w Unii Europejskiej. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Kurczewska, U. 2018. Aktorzy i interesy w politykach publicznych w Unii Europejskiej. Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza Szkoła Główna Handlowa.

Kwiatkowski, B., R. Deščíková, and P. Bouda. 2016. Lobbying—A Risk or Opportunity. Lobbying Regulation in the Polish, Slovak, and Czech Perspective. Krakow: Frank Bold.

Lijphart, A. 1984. Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-One Countries. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Linz, J.J., and A.C. Stepan. 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lührmann, A., and S.I. Lindberg. 2019. A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What is New About It?’. Democratization 26(7): 1095–1113.

Magyar, B., and B. Madlovics. 2020. The Anatomy of Post-Communist Regimes: A Conceptual Framework. Central European University Press.

Mahoney, C. 2007. Lobbying Success in the United States and the European Union. Journal of Public Policy 27(1): 35–56.

Maloney, W.A., G. Jordan, and A.M. McLaughlin. 1994. Interest Groups and Public Policy: The Insider/Outsider Model Revisited. Journal of Public Policy 14(1): 17–38.

Meyer, T., and A. Vetulani-Cęgiel. 2017. From ACTA to TTIP: Lessons Learned on Democratic Process and Balancing of Rights. In Trans-Atlantic Data Privacy Relations as a Challenge for Democracy, vol. 4, ed. D.J.B. Svantesson and D. Kloza. Cambridge: Intersentia.

Müller, J.W. 2014. Eastern Europe Goes South. Foreign Affairs 93(2): 14–19.

O’Dwyer, C. 2018. The Benefits of Backlash: EU Accession and the Organization of LGBT Activism in Postcommunist Poland and the Czech Republic. East European Politics and Societies 32(4): 892–923.

Petrova, T. 2014. From Solidarity to Geopolitics: Support for Democracy among Postcommunist States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Płatek, D., and P. Płucienniczak. 2016. Civil Society and Extreme-Right Collective Action in Poland 1990–2013. Revue d’études comparatives Est-Ouest 47(4): 117–146.

Pospieszna, P. 2014. Democracy Assistance from the Third Wave: Polish Engagement in Belarus and Ukraine. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Pospieszna, P. 2019. Democracy Assistance Bypassing Governments in Recipient Countries Supporting the “Next Generation.” Abingdon: Routledge.

Rozbicka, P., Kamiński, P., and Pospieszna, P. 2019, January. IGPOL Project: Polish Survey Data Report. Birmingham: Aston Centre for Europe, Aston University, Cracow: Institute of Political Science and International Relations, Jagiellonian University, Poznan: Adam Mickiewicz University, Department of Political Culture. Retrieved from www.cigsurvey.eu/data/

Sedelmeier, U. 2014. Anchoring Democracy from Above? The European Union and Democratic Backsliding in Hungary and Romania after Accession. Journal of Common Market Studies 52(1): 105–121.

Obywatelskie Forum Legislacji. 2019. Skrywane projekty ustaw, XII Komunikat Obywatelskiego Forum Legislacji o jakości procesu legislacyjnego na podstawie obserwacji prowadzonej w okresie od 16 maja do 15 listopada 2018 roku oraz podsumowujący aktywność legislacyjną rządu i parlamentu w trzecim roku ich działalności. Warszawa: Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego. Retrieved from www.batory.org.pl/upload/files/Programy%20operacyjne/Forum%20Idei/XII_Komunikat_OFL.pdf

Toepler, S., A. Zimmer, C. Fröhlich, et al. 2020. The Changing Space for NGOs: Civil Society in Authoritarian and Hybrid Regimes. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 31: 649–662.

Ust. d.o.p.p. 2003. Ustawa z dnia 24 kwietnia 2003 r. o działalności pożytku publicznego i o wolontariacie, Dz. U. nr 96 poz. 873.

Ust. lobb. 2005. Ustawa z dnia 7 lipca 2005 r. o działalności lobbingowej w procesie stanowienia prawa, Dz. U. nr 169, poz. 1414.

Ust. RDS. 2015. Ustawa z dnia 24 lipca 2015 r. o Radzie Dialogu Społecznego i innych instytucjach dialogu społecznego, Dz. U. nr 2015, poz. 1240, ze zm.

Van der Borgh, C., and C. Terwindt. 2012. Shrinking Operational Space of NGOs—a Framework of Analysis. Development in Practice 22(8): 1065–1081.

Zombetti. J.P. 2006. The Role of Advocacy in Civil Society. Argumentation 20: 167–183.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a part of the research collaboration with Comparative Interest Group (CIG), and the Polish team IGPOL. Moreover, the authors would like to thank the National Science Centre in Poland for a financial support provided within grants Harmonia (2018/30/M/HS5/00437) and Fuga (Decision No DEC-2014/12/S/HS5/00006). The earlier version of the article was presented at the 2019 ECPR General Conference in Wrocław, Poland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pospieszna, P., Vetulani-Cęgiel, A. Polish interest groups facing democratic backsliding. Int Groups Adv 10, 158–180 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-021-00119-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-021-00119-y