Abstract

In less developed countries such as Kenya, trade is increasingly occurring through, and employment is found within, global and local value chains. Yet, although innovation is widely recognised as crucial for development, the endogenous relationship between small-scale innovations and participation in global value chains (GVCs) has yet to be explored sufficiently. This endogeneity is highlighted using the 3L’s of labels, linkages and learnings as key overlapping factors that affect both the processes of innovation as well as GVC participation. Drawing on a survey of 320 fresh fruit farmers and 55 interviews in Kenya, we develop a novel method to quantify small-scale agricultural innovations, which are categorised into two overarching types. The first, formal, emanate from meeting standard requirements; the second, informal, evolve from local contexts and are less codified. We find that GVC farmers perform more formal innovations, while local farmers perform similar levels of informal innovation to GVC farmers.

Dans les pays moins développés tels que le Kenya, le commerce se passe de plus en plus de la même façon que l’on trouve un emploi, c’est-à-dire par le biais des chaînes de valeur mondiales et locales. Dans le même temps, l’importance de l’innovation à petite échelle est de plus en plus reconnue. Cependant, la relation endogène entre les innovations à petite échelle et les chaînes de valeur mondiales (CVM) n’a pas encore été suffisamment explorée. Empiriquement, en se basant sur un sondage auprès de 320 cultivateurs de fruits frais et sur 55 entretiens au Kenya, nous quantifions systématiquement l’innovation agricole à petite échelle: il y a celles qui émanent de pressions extérieures formelles liées à la chaîne de valuer mondiale; et celles qui évoluent à partir de contextes locaux informels qui sont plus difficiles à codifier. Nous constatons que les agriculteurs de la chaîne de valeur mondiale réalisent des innovations plus formelles, alors que les agriculteurs locaux ainsi que ceux de de la chaîne de valeur mondiale ont des niveaux d’innovation informelle presque similaires. Nous soulignons également que les 3 “L”, c’est-à-dire les labels, liens et leçons apprises, sont des facteurs clés qui se cumulent et impactent à la fois les processus d’innovation ainsi que la participation à la chaîne de valeur mondiale.

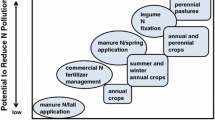

Source: Authors’ construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abrol, D. and Gupta, A. (2014) Understanding the diffusion modes of grassroots innovations in India: A study of honey bee network supported innovators. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 6(6): 541–552.

Ancori, B., Bureth, A. and Cohendet, P. (2000). The economics of knowledge: The debate about codification and tacit knowledge. Industrial and Corporate Change 9(2): 255–287.

Bell, M. (2006) Time and technological learning in industrialising countries: How long does it take? How fast is it moving (if at all)? International Journal of Technology Management 36(1–3): 25–39.

Berdegué, J.A., Biénabe, E. and Peppelenbos, L. (2008) Keys to inclusion of small-scale producers in dynamic markets-Innovative practice in connecting small-scale producers with dynamic markets. In: IIED.

Carter, M.R. and Barrett, C.B. (2006) The economics of poverty traps and persistent poverty: An asset-based approach. The Journal of Development Studies 42(2): 178–199.

Cozzens, S. and Sutz, J. (2012) Innovation in informal settings: A research agenda. In: IDRC, Ottawa, Canada, pp. 1–53.

Dannenberg, P. and Lakes, T. (2013) The use of mobile phones by Kenyan export-orientated small-scale farmers: Insights from fruit and vegetable farming in the Mt. Kenya region. Economia agro-alimentare 21: 55–75.

Deaton, A. (1997) The Analysis of Household Surveys: A Microeconometric Approach to Development Policy. World Bank Publications.

Ernst, D. and Kim, L. (2002) Global production networks, knowledge diffusion, and local capability formation. Research Policy 31(8): 1417–1429.

Evers, B.J., Amoding, F. and Krishnan, A. (2014) Social and economic upgrading in floriculture global value chains: Flowers and cuttings GVCs in Uganda. Capturing the Gains working paper: 39.

Foster, C. and Heeks, R. (2013) Conceptualising inclusive innovation: Modifying systems of innovation frameworks to understand diffusion of new technology to low-income consumers. The European Journal of Development Research 25(3): 333–355.

Foster, C. and Heeks, R. (2014) Nurturing user-producer interaction: Inclusive innovation flows in a low-income mobile phone market. Innovation and Development 4(2): 221–237.

Fromhold-Eisebith, M. (2007) Bridging scales in innovation policies: How to link regional, national and international innovation systems. European Planning Studies 15(2): 217–233.

Gault, F. (2010) Innovation strategies for a global economy: Development, implementation, measurement and management. In: IDRC.

George, G., McGahan, A.M. and Prabhu, J. (2012) Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. Journal of Management Studies 49(4): 661–683.

Gereffi, G. (1999) International trade and industrial upgrading in the apparel commodity chain. Journal of International Economics 48(1): 37–70.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J. and Sturgeon, T. (2005) The governance of global value chains. Review of International Political Economy 12(1): 78–104.

Gertler, M.S. (2003) Tacit knowledge and the economic geography of context, or the undefinable tacitness of being (there). Journal of Economic Geography 3(1): 75–99.

GlobalGAP. (2016). GlobalGAP Crops. Available at: http://www.globalgap.org/uk_en/for-producers/crops/, Accessed 23 February 2016.

Granovetter, M.S. (1973) The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78(6): 1360–1380.

Gulati, R. (1995) Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Academy of Management Journal 38(1): 85–112.

HCDA. (2016) Horticulture Validated Report 2015. Nairobi. http://www.agricultureauthority.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Horticulture-Validated-Report-2014-Final-copy.pdf.

Henderson, J., Dicken, P., Hess, M., Coe, N. and Yeung, H.W.C. (2002) Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Review of International Political Economy 9(3): 436–464.

Hernández, R., Reardon, T. and Berdegué, J. (2007) Supermarkets, wholesalers, and tomato growers in Guatemala. Agricultural Economics 36(3): 281–290.

Horner, R. (2016) A new economic geography of trade and development? Governing south–south trade, value chains and production networks. Territory, Politics, Governance 4(4): 400–420.

Horner, R. and Nadvi, K. (2017) Global value chains and the rise of the Global South: unpacking twenty-first century polycentric trade. Global Networks. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12180.

Kaplinsky, R. et al. (2009) Below the radar: What does innovation in emerging economies have to offer other low-income economies? International Journal of Technology Management & Sustainable Development. 8(3): 177–197.

Knickel, K. et al. (2009) Towards a better conceptual framework for innovation processes in agriculture and rural development: From linear models to systemic approaches. Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 15(2):131–146.

Knorringa, P. et al. (2016) Frugal innovation and development: Aides or adversaries? The European Journal of Development Research 28(2): 143–153.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992) Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the replication of technology. Organization Science 3(3): 383–397.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1993) Knowledge of the firm and the evolutionary theory of the multinationalcorporation. Journal of International Business Studies 24(4): 625–645.

Kolenikov, S. and Angeles, G. (2009) Socioeconomic status measurement with discrete proxy variables: Is principal component analysis a reliable answer? Review of Income and Wealth 55(1): 128–165.

Korzun, M., Adekunle, B. & Filson, G.C. (2014) Innovation and agricultural exports: The case of Sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 6(6), pp. 499–510.

Krauss, J. and Krishnan, A. (2016) Global decisions and local realities: Priorities and producers’ upgrading opportunities in agricultural global production networks. 7. Geneva. https://unfss.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/discussion-paper_unfss_krausskrishnan_dec2016.pdf.

Krishnan, A. (2017) The origin and expansion of regional value chains: The case of Kenyan horticulture global networks. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12162.

Lall, S. and Pietrobelli, C. (2002) Failing to compete: Technology Development and Technology Systems in Africa. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Lall, S. (1987) Learning to Industrialize: The Acquisition of Technological Capability by India. New York: Springer.

Lokshin, M. and Sajaia, Z. (2004) Maximum likelihood estimation of endogenous switching regression models. Stata Journal 4: 282–289.

Lundvall, B.-Å. (2010) National Systems of Innovation: Toward a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning. London: Anthem Press.

Lundvall, B.-Å. and Lema, R. (2014) Growth and structural change in Africa: Development strategies for the learning economy. In: B.-Å. Lundvall (eds.) The Learning Economy and the Economics of Hope. London: Anthem press, p. 327.

Maertens, M. and Swinnen, J.F.M. (2009) Trade, standards, and poverty: Evidence from Senegal. World Development 37(1): 161–178.

Maddala, G.S. (1983) Limited Dependent and Qualitative Models in Econometrics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Maddala, G.S. (1986) Limited-Dependent and Qualitative Variables in Econometrics. Cambridge University Press.

Manyati, T. (2014) Agro-based technological innovation: A critical analysis of the determinants of innovation in the informal sector in Harare, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 6(6): 553–561.

Morrison, A., Pietrobelli, C. and Rabellotti, R. (2008) Global value chains and technological capabilities: A framework to study learning and innovation in developing countries. Oxford Development Studies 36(1): 39–58.

Nadvi, K. (2008) Global standards, global governance and the organization of global value chains. Journal of Economic Geography. 8(3): 323–343.

Neilson, J. and Pritchard, B. (2011) Value Chain Struggles: Institutions and Governance in the Plantation Districts of South India (Vol. 93). John Wiley & Sons.

Nelson, R. (2004) The challenge of building an effective innovation system for catch-up. Oxford Development Studies 32(3): 365–374.

Nelson, R.R. and Winter, S.G. (1982). The Schumpeterian tradeoff revisited. The American Economic Review 72(1): 114–132.

Okello, J. J., Kirui, O., Njiraini, G.W. and Gitonga, Z. (2011) Drivers of use of information and communication technologies by farm households: The case of smallholder farmers in Kenya. Journal of Agricultural Science 4(2): 111.

Parrilli, M.D., Nadvi, K. and Yeung, H.W. (2013) Local and regional development in global value chains, production networks and innovation networks: A comparative review and the challenges for future research. European Planning Studies 21(7): 967–988.

Pesa, I. (2015) Homegrown or Imported?: Frugal innovation and local economic development in Zambia. Southern African Journal of Policy and Development 2: 15–25.

Pickles, J., Barrientos, S. and Knorringa, P. (2016) New end markets, supermarket expansion and shifting social standards. Environment and Planning A 48(7): 1284–1301.

Pietrobelli, C. and Rabellotti, R. (2011) Global value chains meet innovation systems: Are there learning opportunities for developing countries? World Development 39(7): 1261–1269.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The logic of tacit inference. Philosophy 41(155): 1–18.

Ponte, S. and Ewert, J. (2009) Which way is “up” in upgrading? Trajectories of change in the value chain for South African wine. World Development 37(10): 1637–1650.

Ponte, S. and Sturgeon, T. (2014) Explaining governance in global value chains: A modular theory-building effort. Review of International Political Economy 21(1): 195–223.

Popper, K.R. (1972). Objective knowledge: An evolutionary approach. pp. 81–106.

Prabhu, J. and Jain, S. (2015) Innovation and entrepreneurship in India: Understanding jugaad. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 32(4): 843–868.

Radjou, N. and Prabhu, J. (2014) Frugal Innovation: How to do More with Less. London: Profile Books.

Raina, R.S. Joseph, K., Haribabu, E. and Kumar, R. (2009) Agricultural innovation systems and the coevolution of exclusion in India. In: Systems of Innovation for Inclusive Development Project.

Rivers, D. and Vuong, Q.H. (1988) Limited information estimators and exogeneity tests for simultaneous probit models. Journal of Econometrics 39(3): 347–366.

Rao, E.J.O. and Qaim, M. (2011) Supermarkets, farm household income, and poverty: Insights from Kenya. World Development 39(5): 784–796.

Spielman, D.J. (2005) Innovation Systems Perspectives on Developing-Country Agriculture: A Critical Review. Rome, Italy: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). International Service for National Agricultural Research (ISNAR) Division.

STEPS Centre. (2010) Innovation, Sustainability, Development: A New Manifesto. Brighton, UK: STEPS Centre.

Tallontire, A., Opondo, M., Nelson, V. and Martin, A. (2011) Beyond the vertical? Using value chains and governance as a framework to analyse private standards initiatives in agri-food chains. Agriculture and Human Values 28(3): 427–441.

Trost, R.P. (1981) Interpretation of error covariances with nonrandom data: An empirical illustration of returns to college education. Atlantic Economic Journal 9(3): 85–90.

Uzzi, B. (1996) The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: The network effect. American Sociological Review 61: 674–698.

van Beers, C., Knorringa, P. and Leliveld, A. (2014) Frugal innovation in Africa: Towards a research agenda. In: Paper presented at 14th EADI General Conference, Bonn, Germany, 23 June.

Viotti, E.B. (2002) National learning systems: A new approach on technological change in late industrializing economies and evidences from the cases of Brazil and South Korea. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 69(7): 653–680.

Wooldridge, J.M. (2002) Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

World Bank. (2010) Innovation Policy: A Guide for Developing Countries. World bank: Washington.

Zanello, G. et al. (2016) The creation and diffusion of innovation in developing countries: A systematic literature review. Journal of Economic Surveys. 30(5): 884–912.

Zeschky, M., Widenmayer, B. and Gassmann, O. (2011) Frugal innovation in emerging markets. Research-Technology Management 54(4): 38–45.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from Peter Knorringa, Kunal Sen, Rory Horner, Kate Meagher, Stephanie Barrientos and Khalid Nadvi for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We also thank the reviews for their valuable insights.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Linkages – Breakdown of Relationships

Actors | Relationship of farmer with actors | GVC | LVC |

|---|---|---|---|

Seed suppliers | 0 = weak (% of each farmer category) | 2.68 | 0.41 |

1 = intermediate (% of each farmer category) | 63.6 | 50 | |

2 = strong (% of each farmer category) | 33.72 | 49.59 | |

Agro-vets | 0 = weak (% of each farmer category) | 4.6 | 7.41 |

1 = intermediate (% of each farmer category) | 51.72 | 62.3 | |

2 = strong (% of each farmer category) | 43.68 | 29.59 | |

Local credit givers | 0 = weak (% of each farmer category) | 3.45 | 0.00 |

1 = intermediate (% of each farmer category) | 90.42 | 88.21 | |

2 = strong (% of each farmer category) | 6.13 | 11.79 | |

Extension officers | 0 = weak (% of each farmer category) | 12.2 | 44.83 |

1 = intermediate (% of each farmer category) | 47.56 | 36.78 | |

2 = strong (% of each farmer category) | 40.24 | 18.39 | |

Main buyers (exporters for GVC farmers and local buyers for LVC) | 0 = weak (% of each farmer category) | 19.51 | 54.39 |

1 = intermediate (% of each farmer category) | 44.31 | 24.72 | |

2 = strong (% of each farmer category) | 33.74 | 20.88 | |

Brokers | 0 = weak (% of each farmer category) | 31.42 | 19.51 |

1 = intermediate (% of each farmer category) | 50.57 | 36.99 | |

2 = strong (% of each farmer category) | 14.56 | 8.54 |

Appendix B: Summary of variables used in regression

Variables | Variable explanation | Stage 1 regression | Stage 2 regression |

|---|---|---|---|

Labels | Having a local code of conduct or international certification dummy; values in % | Yes | Yes |

Tacit learning × linkages | Interaction of total share of tacit learning with index of backward/forward linkages | Yes | Yes |

Explicit learning × linkages | Interaction of total share of explicit learning with index of backward/forward linkages | Yes | Yes |

Asset Index | Index of assets possessed before participation in current chain | Yes | Yes |

Alternate livelihoods | Other livelihoods possessed dummy; values in % | Yes | Yes |

Sex | male dummy; values in % | Yes | Yes |

Part of farmer group | Membership if farmer group dummy; values in % | Yes | Yes |

Rejection levels | Dummy for if they have rejections; values in % | Yes | Yes |

Duration | Number of years in specific chain | Yes | No |

Contract | Dummy if they have a contract with main buyer | Yes | No |

Dependent variables | Binary variable GVC farmer or not | Index of formal innovations; Index of informal innovations |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krishnan, A., Foster, C. A Quantitative Approach to Innovation in Agricultural Value Chains: Evidence from Kenyan Horticulture. Eur J Dev Res 30, 108–135 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0117-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-017-0117-0