Abstract

The concept of dry ports has gained significant interest among practitioners and researchers in the last decade. Consequently, publications on this topic have followed this development, and today there are more than 100 papers available in the Scopus and Science Direct databases, compared with only two papers in 2007. The purpose of this paper is to summarize current scientific knowledge on the phenomenon and to identify research outcomes, trends, and future research implications by conducting a systematic literature review (SLR). SLR is an explicit and reproducible method that ensures the reliability and traceability of the results. The selection of relevant papers was performed independently by each author using Rayyan QCRI software; the coding and analysis were conducted with the help of NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Findings show that the research area is largely represented by qualitative cases and optimization studies covering various aspects of dry ports. Dry port examples around the world differ based on location, functions, services, ownership, and maturity level. Although the research area is young and discrete, five main thematic areas are identified: debate on the concept, environmental impact, economic impact, performance impact, and dry ports from a network perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The maritime leg of the intermodal transport chain uses larger ships to cope with the demand for increased containerized transport and to fully utilize economies of scale (Haralambides 2019). Consequently, seaports face challenges related to terminal capacity, fairway drafts, equipment to handle those vessels, and, in particular, challenges related to inland access. Despite heavy investments in container terminal capacity and equipment, larger ships and larger flows of containers exert a severe strain on seaports, and progress in seaport and hinterland operations must therefore match this growth. Efficient handling and distribution of cargo to and from the hinterland is crucial for the overall performance of seaports and for the whole supply chain. Research addressing the effect of hinterland distribution on seaport performance has gained importance in recent years (see, e.g., Haralambides 2017; Lättilä et al. 2013; Monios 2011). Efficiency in the hinterland part of transport chains has generally not mirrored the progress at sea. Hence, environmental problems related to the transport sector and the role that logistics systems can play in reducing environmental effects are garnering increasing attention. However, until recently, logistics concepts have not been extensively researched regarding their role in mitigating environmental impacts. One of the concepts with the potential to reduce environmental impacts related to the seaport transport system is the dry port.

The most widely used definition of a dry port is the one suggested by Roso et al. (2009): “A dry port is an inland intermodal terminal directly connected to seaport(s) with high capacity transport mean(s), where customers can leave/pick up their standardised units as if directly to a seaport.” However, as noted by Rodrigue et al. (2010), “no two dry ports are the same.” Dry ports exist in very different forms and arrangements under different terms around the world, and they differ in location, functionality, maturity level, ownership, and initiation processes. Consequently, the research has branched out into different fields, resulting in a diversity of dry port publications using different research designs and focusing on different aspects of the same phenomenon. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to summarize current scientific knowledge on the phenomenon and to identify research outcomes, trends, and future research implications by conducting a systematic literature review (SLR).

2 Methodology

2.1 Research design

A literature review serves as a tool for assessing and evaluating scientific knowledge in a particular research area and identifying potential gaps (Tranfield et al. 2003). Seuring et al. (2012) strongly recommend following a systematic method in conducting a review; otherwise the review may lack replicability and traceability. Compared with a classical (narrative) literature review, a systematic literature review (SLR) follows more rigorously predefined steps. Durach et al. (2017) reviewed core papers on SLR and proposed a guideline for conducting an SLR (Table 1). In addition, SLRs are often complemented with demographic data about the research community (Seuring et al. 2012). The current review follows the steps synthesized by Durach et al. (2017) and suggestions made by Seuring et al. (2012), Table 1.

2.2 Retrieving relevant literature/search strategy

The search was conducted in Scopus and Science Direct databases in July 2019, and the filtering process was performed independently by each author using Rayyan QCRI software, as suggested by Ouzzani et al. (2016). The search string “dry port” OR “dry ports” OR “dryport*” OR “dry-port*” AND “transport*” was used for abstracts, keywords, and titles. The initial list (354 papers) was checked for duplicates; after the duplicates (35 papers) were eliminated/merged, the remaining research items (319 papers) were analyzed for relevance, first by screening the abstracts and then in some cases by screening the full text. At the same time, the research items not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded. The detailed results of this screening process are presented in Table 2.

Most of the excluded items were those that did not correspond to the focus of our review; the remaining were excluded because they were considered to be background articles (relating to dry ports or mentioning the term “dry port” but not focusing on the phenomenon), they were of the wrong publication type (report, conference, or other than peer-reviewed type of publication) or written in a language other than English, or the full text of the item was not available.

2.3 Analytical approach

The first step, bibliometric analysis, is related to general data regarding the research field and employs a quantitative approach to the research structure and development of the research field based on analysis of related publications. The second part of the analysis is content-based: the framework for this analysis evolves during the survey of the papers by identifying themes and coding them, and this review process is of an iterative nature. Already in the exclusion/inclusion process, Rayyan QCRI software facilitated the grouping of the selected papers according to thematic areas. As suggested by Agamez-Arias and Moyano-Fuentes (2017), we grouped the selected papers into subcategories (sub-lines) based on similar focus, and those subcategories were subsequently grouped into main categories (themes or main lines) of research based on their interrelationships. However, many papers had multiple areas of focus, and in those cases it was not possible to draw a sharp distinction; consequently, a paper could end up in a few categories. The content analysis of the selected papers was conducted with the aid of NVivo 11.4.3 qualitative research analysis software, which allowed us to create a database of all reviewed papers that facilitated the review process by providing easy access to the coded data.

3 Bibliometric aspects

The research on dry ports is new and emerging. It has grown from two journal publications in 2007 to over 100 a decade later. A search of the databases revealed the earliest item, dated 1984, referring to a similar phenomenon under the same term:

A proposal to establish the Port of Memphis as a dry port for New Orleans is presented. Export cargo in container would be assembled from all over the country at Memphis and then be carried to New Orleans by contract trains for shipment; the imported goods would be transported to Memphis for distribution. (“Memphis ‘dry port’ link to N.O. urged,” 1984).

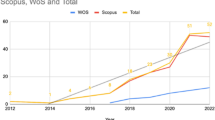

The item itself was not available for review, and thus it is not included in this paper. However, the concept of a dry port was described in detail in an academic journal in 2009 (Roso et al. 2009), with several earlier publications referring to the term “dry port” but without explicitly defining it. Since then, interest in the topic has been evident within academia; the number of publications has grown every year (Fig. 1). The fall in the number of journal publications in 2014 may have resulted from the publication of two special issues in previous years. In addition, a book published in 2013 titled Dry ports—a global perspective contained 12 articles, all focused on dry ports and their application in different regions (Bergqvist et al. 2013). The book was not available in the reviewed databases and therefore was not included here, but the publishing of special issues and books in itself demonstrates the increasing interest in the subject.

Fifty-two journals published the reviewed articles, with the Journal of Transport Geography and Transportation Research Part E having the greatest share (Fig. 2). The former consists chiefly of papers using a qualitative approach and those dealing with the development of the concept and its application in different regions, while the latter covers mostly quantitative approaches on modeling and optimization of environmental and economic issues related to dry ports.

As the research focus of the studied papers varies, so do the methods applied. Most of the papers (≈ 50%) used a case study and multiple cases as a research strategy, followed by modeling of either existing systems/cases or theoretical ones. With regard to data collection, most of the methods used were interviews and a mixture of secondary evidence such as trade journals, reports, previous studies, archives, and websites. Very few studies were based on observations, these usually in connection with interviews or site visits, and only about 10% were based on surveys. Overall, most of the papers do not provide a solid description of their methodology.

4 Research outcomes

Although the field of research is heterogeneous, the reviewed papers could be divided into broad thematic areas and further into subcategories; thematic analysis was therefore conducted. Identified thematic areas further analyzed include concept issues, environmental, economic, and performance impacts and network perspectives. Their subcategories are presented below.

4.1 Concept

4.1.1 Definition and taxonomy

Although the concept gained attention in academia about a decade ago, the setup of an intermodal terminal directly connected to a seaport existed long before. Nevertheless, in 2009, Roso et al. (2009) coined a dry port definition that was very specific in meaning: “A dry port is an inland intermodal terminal directly connected to seaport(s) with high capacity transport mean(s), where customers can leave/pick up their transhipment units as if directly to a seaport.” To meet the criteria of a dry port, an intermodal inland terminal facility should satisfy two parameters:

- 1.

an inland extension of a seaport, i.e., serving as a seaport’s interface inland, offering services that are usually available at the seaport;

- 2.

connection to a seaport by a “high-capacity transportation means,” which often implies rail and less frequently barge/inland waterway transportation.

However, there is still no definitive consensus about which term or definition to use for the facilities fitting the above description (Rodrigue et al. 2010). Nevertheless, the term “dry port” has been advocated by many researchers, as it captures the broad understanding scholars have regarding the concept (Witte et al. 2019). The review papers have suggested a number of dry port classifications, i.e., different taxonomies (Table 3).

Functions of dry ports vary depending on the type of facility, ranging from basic logistics services (e.g., transhipment, storage) to a variety of customer-oriented services including cargo consolidation and deconsolidation, maintenance and repair, track and trace, custom clearance, information processing and forwarding (Ng and Gujar 2009a, b; Beresford et al. 2012; Jeevan et al. 2015b). Dry port functions depend largely on the stakeholders involved, regulations, and relationships with seaports and the hinterland.

4.1.2 Development of the concept

Attempts to further develop the concept have been substantial. Veenstra et al. (2012) conceptualized the ability of a seaport to influence hinterland container flows and introduced the extended gate concept, where an “extended gate is an inland intermodal terminal directly connected to seaport terminal(s) with high capacity transport means, where customers can leave or pick up their transhipment units as if directly with a seaport, and where the seaport terminal can choose to control the flow of containers to and from the inland terminal” (author’s italics). The idea fits with the “outside-in” types of dry ports introduced earlier by Wilmsmeier et al. (2011), that is, dry port “developed by port authorities, port terminal operators or ocean carriers.” Veenstra et al. (2012) conclude that “at a conceptual level, extended gates do not go beyond the dry port idea.” Dry ports differ from other terminals chiefly by enabling high-capacity access to and from seaports. Rodrigue et al. (2010) elaborate using the term “inland port,” which is widely used in the United States and better encompasses the relationship between seaport, inland terminals and logistics services. Further, Rodrigue and Notteboom (2012) discuss differences between dry ports in North America and Europe based on the features of transport/railway systems. A substantial portion of the reviewed publications deal with applications of the concept in different regions, including India (Haralambides and Gujar 2012), China (Beresford et al. 2012), South America, and Europe (Henttu and Hilmola 2011). Nguyen and Notteboom (2019) contributed to the generalization of knowledge on dry ports by identifying common patterns in a global selection of 107 dry ports. The authors established a correlation between seaport and dry port parameters, showing that dry port parameters are strongly related to the characteristics of the seaport served.

4.2 Environmental impact

Dry ports as elements of a hinterland distribution network stimulate a modal shift, which leads to less traffic and congestion at seaport gates and seaport cities, and reductions in emissions by as much as 32–45% (Lättilä et al. 2013). In seaport cities and regions, road congestion and associated costs of road accidents decrease. However, dry ports need to be integrated into seaport hinterland transportation systems, and transportation solutions should be favorable for stakeholders and supported by policies and regulations (Regmi and Hanaoka 2012).

Castagnetti (2012) discusses efforts to address environmental issues within the framework of European projects promoting the utilization of faster and heavier freight trains for hinterland distribution. Ng et al. (2013) touch upon the issue of how climate change may be considered in strategic plans of hinterland transportation nodes, i.e., seaports and dry ports. Environmental benefits are often discussed in the context of economic benefits. For example, a study conducted in Finland concludes that implementation of dry port networks would lead to a “reduction in both emissions and total transportation costs” (Henttu and Hilmola 2011). However, in cases of poor planning or failure to establish well-functioning transportation schedules between seaports and dry ports, emissions could increase rather than decrease (Hanaoka and Regmi 2011). Finally, attitudes towards environmental benefits vary much depending on the country: in India, where an oversupply of dry ports has been reported, public dry ports are focused on their own survival or, in other words, on maximizing profit, but not on reducing emissions. A similar situation is typical for publicly owned dry ports that “completely ignore CO2 emission impacts” (Haralambides and Gujar 2012).

4.3 Economic impact

4.3.1 Regional development

Since a dry port should act as the seaport’s inland interface, shifting port services to an inland region provides a stimulus for development and generates new employment (Ng and Tongzon 2010). Furthermore, regional development might positively influence competitiveness by maximizing the use of existing infrastructure and generating trade volumes. Ng and Tongzon (2010) went so far as to declare that dry ports were catalysts for regional development, at least in India. In the case of Iran, establishing a dry port in the province of Yazd could potentially increase freight transit in that country and influence development (Dorostkar et al. 2016).

4.3.2 Investments

Building new transport facilities requires significant financial investment and careful consideration of stakeholders’ interests, but it also has the potential to provide numerous benefits. A number of parameters should be satisfied in order to establish a dry port. Implementation of the extended gate concept is seen as a good solution for ports in East Africa, but it would require a joint effort by multiple stakeholders involving planning and funding institutions, both private and governmental. Developing a dry port is an investment-intensive project in which there could be various options for obtaining funds. Public–private partnership (PPP) investment appears to be a viable model for the provision of necessary funds. This was discussed by Panova and Hilmola (2015), who compared dry port investment strategies in European countries to examples from New Zealand, India, and Turkey. They suggested PPP as the most convenient investment mechanism for funding dry port development in Russia. Public investment alone, on the other hand, may at times cause economic insolvency or excess capacity, as has been observed in certain cases in India (Haralambides and Gujar 2011). The authors conclude that PPP investments should be supported by governmental pricing policies and guidelines.

4.3.3 Feasibility of implementation

Lack of regulation, conflicting regulations, or regulations that have hindered the establishment of dry ports have often been cited in the literature. The feasibility of building dry ports in Iran was studied by Dorostkar et al. (2016), who showed that establishing rail shuttle services between potential dry ports and seaports was not realistic given the underdeveloped railway infrastructure. On the other hand, in the (former) Indochina area,Footnote 1 the implementation of dry ports is seen as a stimulus for the development of intermodal transportation. However, new challenges related to financing have arisen (Do et al. 2011). The major constraints on establishing dry ports in Russia are related to financing and investment risks (Panova and Korovyakovsky 2013).

4.3.4 Profitability

Implementation of dry ports can lead to an overall reduction in a country’s transportation costs if an optimal number of facilities are put into operation in strategic locations (Henttu and Hilmola 2011). For example, in Finland, it was shown that the most significant cost reduction could be achieved by implementing a strategic number (4–6) of dry ports (Henttu et al. 2011). In Russia, the introduction of new dry ports could decrease the overall transit time of cargo through the Trans-Siberian Railway System (Panova 2011). Bergqvist et al. (2010) studied factors that influence the pace and process of dry port establishment, and their conclusions, based on two case studies in Sweden, presented a list of factors including the overall profitability of the project, location, presence of a “political entrepreneur,” and the presence of large local shippers. These are examples of general advantage/profitability related to the existence of dry ports in a transport system. More specific examples, for example, the profitability of specific services related—or available—to dry ports, can be found in Qiu et al. (2015), among others.

4.4 Performance impact

4.4.1 Dry port operations optimization

Studies have been conducted on optimization of dry port operations from different perspectives. Crainic et al. (2015) focus on the tactical level of transportation planning with the involvement of dry ports. Their model addresses the problem of optimizing a shuttle schedule between dry ports and seaports. A study by Chang et al. (2015) focuses on cost optimization for the stakeholders involved, including installation, storage, and transportation costs. Underperforming dry ports and dry ports facing operational issues are studied mainly in Asia. Ng and Gujar (2009a, b) study dry ports in India with a focus on regional development around dry ports, which could attract users. Value-added services offered at dry ports can make a region more attractive to the actors in the immediate vicinity, as well as attract potential new users from more remote locations. Jeevan et al. (2017) study Malaysian dry ports, identifying primary factors that influence their performance, such as information sharing, availability of value-added services such as customs clearance, the capacity of the facility, and the location of dry ports. Alam (2016) identified factors such as issues with direct rail connection to the seaport that hinder efficient dry port operations in Pakistan and concluded that supportive polices are needed to overcome such issues and improve dry port performance.

4.4.2 Seaport performance

Improving railway infrastructure and establishing dry ports are important elements in a hinterland consolidation-distribution system, and the latter needs to be regulated and supported by policies and special institutions. Mirzabeiki et al. (2016) studied the effects of hinterland transportation between seaport and dry port with the inclusion of a collaborative tracking and tracing (CTT) system. The study concluded that CTT positively affects the speed of operations, resource utilization, reliability, safety, and data quality. Fanti et al. (2015) addressed the optimization of lead time in both dry ports and seaport areas: the results of their modeling supported suggestions for reorganizing workflow in order to better utilize human resources. Qiu et al. (2015) looked into the problem of storage pricing at dry ports and its dependency on seaport pricing. Xie et al. (2017) focused on the problem of repositioning and coordinating empty containers at dry ports and seaports. By establishing dry ports, seaports could increase capacity without expanding their seaport terminals, as in the case—among many others—of Russian ports (Korovyakovsky and Panova 2011). In this way, seaports free up space for sensitive goods such as alcohol and tobacco, and gain a competitive advantage as a result of better access to hinterland areas (Rathnayake et al. 2013).

4.5 Network perspective

4.5.1 Dry port as an element of the transport network/supply chain

Once established, a dry port becomes part of a competitive transportation system that has numerous stakeholders with diverse strategies and interests. The growth stage of dry port development, referred to as “bidirectional development—outside-and-inside,” implies a joint effort towards dry port development by different actors engaged in hinterland transportation, and coincides with the active operation and business improvement phase of the dry port (Bask et al. 2014). Ng et al. (2013) present evidence from Brazil, where governmental institutions act either in support of or as an impediment to dry port development. That is, coordination between dry ports and seaports can be impeded due to lack of regulations, or, on the contrary, various difficulties in seaport operations might enhance dry port utilization. According to Wilmsmeier et al. (2011), the direction of dry port development as inside-out or outside-in is determined by existing policies for both public and private sectors. This conclusion is drawn from studying cases in Sweden, the USA, and Scotland (ibid). However, in the case of China, lack of coordination between institutions at different levels and the inability to interpret policies issued at higher levels in a beneficial manner hinder dry port development (Beresford et al. 2012). The problems are associated with the planning, operation, and regulation of hinterland transportation networks that are shared between authorities. Uncertainty, combined with new regulations, can slow the development of dry ports, i.e., they can deter long-term planning and investment (Ng and Tongzon 2010). On the other hand, supportive policies might accelerate a growing business, as illustrated by Jeevan et al. (2015a) in the case of container transportation through ports to the Malaysian hinterland. Strategies oriented towards better connectivity with foreign markets encourage seaports to develop connectivity with hinterland areas based on rail transport and, where possible, inland waterway transport (Notteboom and Yang 2017). Dry ports are elements of a hinterland transportation system, and their development depends on the state of other infrastructure.

4.5.2 Location issues and optimization

Awad-Núñez et al. (2016) argued that important location criteria include accessibility to a rail network, high-capacity roads, and seaports, and that dry port location decisions tend “to cater more to political preferences rather than technical criteria”. Ng and Cetin (2012) studied examples from India, emphasizing the importance of dry ports for a developing economy. Dry ports in the studied area deviated from optimal locations due to the influence of production facilities on location decisions, informal relationships between stakeholders, and policy restrictions. Flämig and Hesse (2011) also adopted a long-term perspective and investigated the positioning of dry ports. The authors considered the consequences that might arise with the development of dry ports as elements of port regionalization strategies, i.e., changes in transportation flow management, land use, governance, and planning. An interesting perspective was taken by Wang et al. (2018), who suggested the closure of existing dry ports with low throughput, together with the opening of new dry ports in more strategic locations, similar to the case of India, where oversupply of dry ports had led to economic losses. However, as Wang et al. (2018) noted, it might be practically difficult to eliminate inefficient infrastructure in light of the issue of “project image,” often tied to the image of local officials. Another body of publications focuses on finding optimal dry port locations and selecting better optimization methods. Ambrosino and Sciomachen (2014) investigated opportunities for establishing dry port networks in proximity to the port of Genoa, Italy, considering geographical location, volumes, mono- and multimodal approaches, and options for multiple or single mid-range dry ports. Feng et al. (2013) proposed implementation of dry ports in the Fujian region of China, dedicated to a seaport, or shared among different seaports—something that could facilitate transportation cost reduction. Most importantly, success in facility placement depends greatly on infrastructure development, and, as noted by Rathnayake et al. (2013), “any place” within a proper transportation network is suitable for a dry port.

5 Trends

The research field has grown in different directions, but only a few trends have been observed. First, the dry port concept has gained significant recognition in the transportation research field, as can be seen in Fig. 1, with the number of publications growing every year. Figure 3 is more specific, showing the trend or popularity of different thematic areas within the field of dry ports. Although the discussion on terminology and taxonomy periodically reappears in the reviewed publications, overall, publications with a strong focus on further defining the concept do not prevail. From Fig. 3 it is obvious that network perspective and performance impact are the most popular themes. Also, the two themes are closely related: a network perspective takes into consideration different forms of location optimization and dry port feasibility in different regions which, through their consequences, relate to dry port performance. In both themes, a quantitative approach to the problem prevails.

Aspects related to dry port functions, strategies, and operations might be constructed and conceptualized from already published case studies and new empirical evidence. Research has taken a perspective on dry ports which investigates the phenomenon as an element of a hinterland transportation system, often as an element of a seaport–dry port dyad (viewing it as a port regionalization concept). The environmental perspective is more in focus in recent studies on dry ports, but very few publications consider the broader perspective of dry port sustainability. Finally, a significant portion of research has focused on models for the optimal location of dry ports within the hinterland of a seaport. The knowledge generated has great potential to assist in the implementation of dry ports that are currently under consideration, to minimize the risk of insufficient cargo flows or excess infrastructure.

6 Future implications

Dry ports are a part of hinterland transportation systems, and their implementation can be initiated by different actors in the transport system. Such stakeholders have different objectives that could be fulfilled by developing such a facility. Benefits resulting from the implementation/availability of dry ports are summarized in Table 4. They mainly fall into the categories of sustainable development, i.e., social, economic, and environmental benefits. Table 4 shows numerous benefits extracted from the reviewed papers. Most of the benefits identified in this review are of an economic nature, although the concept has gained its popularity due to a range of environmental benefits identified.

The body of knowledge studied here covers thematic areas such as the debate on the concept itself, i.e., definition and taxonomy; environmental and economic impacts, usually through investigation of dry port applications in different regions; performance impact through dry port optimization and impact on seaport performance; and dry ports from a network perspective, as an element of a transportation network by different location optimization studies. Studies addressing the most commonly represented thematic areas, i.e. a network perspective on dry ports or performance impacts, are based on quantitative approaches, but without taking into consideration, at least to a noticeable extent, the perspectives of the variety of actors involved. We therefore call for a more qualitative approach to the problem, which is in line with the recommendations of Gammelgaard (2004) in a study related to schools in logistics research: “[…]The actors’ approach is highly contextual and argues that it is impossible to make predictions based on external cause-effect-relations of social reality due to human beings’ intentionality. Therefore, an understanding of reality requires an investigation of intentions, primarily via qualitative studies.” (Gammelgaard 2004, p. 4).

Dry ports face challenges in their implementation and development phases. These relate to existing social, political, environmental, and financial regulations, or the lack thereof, and to technical and technological development, land and infrastructure use, location and optimization issues, development and availability of infrastructure, stakeholder interests, and investments and a competitive business environment. At the same time, our research shows that dry ports could bring significant benefits to the stakeholders involved in hinterland transport operations by improving distribution systems, reducing direct and indirect logistics costs, stimulating regional development, and lowering the level of transportation emissions.

7 Conclusion

One hundred and two publications related to dry ports were extracted from the Scopus and Science Direct databases and reviewed in order to identify the main research themes, assess the current state of scientific knowledge, and outline research trends and future implications. The dry port concept has gained significant attention among researchers all around the world, mainly due to its potential to improve hinterland intermodal transportation, generate economic benefits, and reduce environmental impacts. In addition to research related to the development of the dry port concept itself, studies on environmental, economic, and performance impacts of dry ports, as well as dry ports from a network perspective, have also been carried out. A variety of methods have been used, but the research is represented predominantly by qualitative cases and quantitative modeling and optimization studies, with very few publications based on surveys of shippers or transport operators. This attention among researchers corresponds to the transport industry’s interest in the phenomenon of dry ports that is represented in different forms around the world, fulfilling different purposes for various stakeholders. Consequently, the concept should be further studied by including multiple actors’ perspectives. The fact that the number of peer-reviewed journal publications grew from two to over 100 in slightly over a decade shows a clear trend of interest in dry ports and indicates that this is an important emerging area of research.

Notes

Today comprising Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

References

Agamez-Arias, A.-M., and J. Moyano-Fuentes. 2017. Intermodal transport in freight distribution: A literature review. Transport Reviews 37: 782–807.

Alam, J. 2016. Role of effective planning process in boosting dry port effectiveness: A case study of central Pakistan. International Journal of Supply Chain Management 5: 153–164.

Ambrosino, D., and A. Sciomachen. 2014. Location of mid-range dry ports in multimodal logistic networks. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences 108: 118–128.

Awad-Núñez, S., F. Soler-Flores, N. González-Cancelas, and A. Camarero-Orive. 2016. How should the sustainability of the location of dry ports be Measured? Transportation Research Procedia 14: 936–944.

Bask, A., V. Roso, D. Andersson, and E. Hämäläinen. 2014. Development of seaport-dry port dyads: Two cases from Northern Europe. Journal of Transport Geography 39: 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.06.014.

Beresford, A., S. Pettit, Q. Xu, and S. Williams. 2012. A study of dry port development in China. Maritime Economics & Logistics 14: 73–98.

Bergqvist, R., G. Falkemark, and J. Woxenius. 2010. Establishing Intermodal Terminals. World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research 3 (3): 285–302.

Bergqvist, R., G. Wilmsmeier, and K. Cullinane (eds.). 2013. Dry ports: A global perspective: challenges and developments in serving hinterlands, 2013. Surrey, England And Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Castagnetti, F. 2012. Facing up the congestion and environmental challenges of Europe. Procedia: Social And Behavioral Sciences 48: 12–20.

Chang, Z., T. Notteboom, and J. Lu. 2015. A two-phase model for dry port location with an application to the port of Dalian in China. Transportation Planning and Technology 38: 442–464.

Crainic, T.G., P. Dell’Olmo, N. Ricciardi, and A. Sgalambro. 2015. Modeling dry-port-based freight distribution planning. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, Engineering and Applied Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2015.03.026.

Do, N.-H., K.-C. Nam, and Q.-L.N. Le. 2011. A consideration for developing a dry port system in Indochina area. Maritime Policy and Management 38: 1–9.

Dorostkar, E., S. Shahbazi, and S.A. Naeini. 2016. The effect of forming dry port in spatial and regional planning system in Yazd Province. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 11: 145–152. https://doi.org/10.3923/jeasci.2016.145.152.

Durach, C.F., J. Kembro, and A. Wieland. 2017. A new paradigm for systematic literature reviews in supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management 53: 67–85.

Fanti, M.P., G. Iacobellis, W. Ukovich, V. Boschian, G. Georgoulas, and C. Stylios. 2015. A simulation based decision support system for logistics management. Journal of Computational Science 10: 86–96.

Fazi, S., and K.J. Roodbergen. 2018. Effects of demurrage and detention regimes on dry-port-based inland container transport. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 89: 1–18.

Feng, M., J. Mangan, and C. Lalwani. 2012. Comparing port performance: Western European versus eastern Asian ports. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 42: 490–512.

Feng, X., Y. Zhang, Y. Li, and W. Wang. 2013. A location-allocation model for seaport-dry port system optimization [WWW document]. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/309585.

Flämig, H., and M. Hesse. 2011. Placing dryports. Port regionalization as a planning challenge: The case of Hamburg, Germany, and the Süderelbe. Research in Transportation Economics, Intermodal Strategies for Integrating Ports and Hinterlands 33: 42–50.

Gammelgaard, B. 2004. Schools in logistics research? International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 34: 479–491.

Hanaoka, S., and M.B. Regmi. 2011. Promoting intermodal freight transport through the development of dry ports in Asia: An environmental perspective. IATSS Research 35: 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iatssr.2011.06.001.

Haralambides, H., and G. Gujar. 2012. On balancing supply chain efficiency and environmental impacts: An eco-DEA model applied to the dry port sector of India. Maritime Economics and Logistics 14: 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1057/mel.2011.19.

Haralambides, H., and G. Gujar. 2011. The Indian dry ports sector, pricing policies and opportunities for public-private partnerships. Research in Transportation Economics 33: 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2011.08.006.

Haralambides, H.E. 2017. Globalization, public sector reform, and the role of ports in international supply chains. Maritime Economics and Logistics 19 (1): 1–51.

Haralambides, H.E. 2019. Gigantism in container shipping, ports and global logistics: A time-lapse into the future. Maritime Economics and Logistics 21 (1): 1–60.

Henttu, V., and O.-P. Hilmola. 2011. Financial and environmental impacts of hypothetical Finnish dry port structure. Research in Transportation Economics, Intermodal Strategies for Integrating Ports and Hinterlands 33: 35–41.

Henttu, V., L. Lättilä, and O.-P. Hilmola. 2011. Optimization of relative transport costs of a hypothetical dry port structure. Transport and Telecommunication 12: 12–19.

Jeevan, J., S. Chen, and E. Lee. 2015a. The challenges of Malaysian dry ports development. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics 31: 109–134.

Jeevan, J., H. Ghaderi, Y.M. Bandara, A.H. Saharuddin, and M.R. Othman. 2015b. The implications of the growth of port throughput on the port capacity: The case of Malaysian major container seaports. International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy 3: 84–98.

Jeevan, J., N.H.M. Salleh, K.B. Loke, and A.H. Saharuddin. 2017. Preparation of dry ports for a competitive environment in the container seaport system: A process benchmarking approach. International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy 7: 19–33.

Khaslavskaya, A., and V. Roso. 2019. Outcome-driven supply chain perspectives on dry ports. Sustainability 11: 1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11051492.

Korovyakovsky, E., and Y. Panova. 2011. Dynamics of Russian dry ports. Research in Transportation Economics 33: 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2011.08.008.

Lättilä, L., V. Henttu, and O.-P. Hilmola. 2013. Hinterland operations of sea ports do matter: Dry port usage effects on transportation costs and CO2 emissions. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 55: 23–42.

Memphis “dry port” link to N.O. urged., 1984.. PORT RECORD 42, 21.

Mirzabeiki, V., V. Roso, and P. Sjöholm. 2016. Collaborative tracking and tracing applied on dry Ports. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management 25: 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLSM.2016.079834.

Monios, J. 2011. The role of inland terminal development in the hinterland access strategies of Spanish ports. Research in Transportation Economics, Intermodal Strategies for Integrating Ports and Hinterlands 33: 59–66.

Ng, A.Y., and G.C. Gujar. 2009a. Government policies, efficiency and competitiveness: The case of dry ports in India. Transport Policy 16: 232–239.

Ng, A.K., and J.L. Tongzon. 2010. The transportation sector of India’s economy: Dry ports as catalysts for regional development. Eurasian Geography and Economics 51: 669–682.

Ng, A.K.Y., and I.B. Cetin. 2012. Locational characteristics of dry ports in developing economies: Some lessons from northern India. Regional Studies 46: 757–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2010.532117.

Ng, A.K.Y., F. Padilha, and A.A. Pallis. 2013. Institutions, bureaucratic and logistical roles of dry ports: The Brazilian experiences. Journal of Transport Geography, Institutions and the Transformation of Transport Nodes 27: 46–55.

Ng, K.Y.A., and G.C. Gujar. 2009b. The spatial characteristics of inland transport hubs: Evidences from Southern India. Journal of Transport Geography 17: 346–356.

Nguyen, L.C., and T. Notteboom. 2019. The relations between dry port characteristics and regional port-hinterland settings: Findings for a global sample of dry ports. Maritime Policy and Management 46: 24–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2018.1448478.

Notteboom, T., and Z. Yang. 2017. Port governance in China since 2004: Institutional layering and the growing impact of broader policies. Research in Transportation Business & Management, Revisiting Port Governance and Port Reform: A Multi-country Examination 22: 184–200.

Othman, M.R., J. Jeevan, and S. Rizal. 2016. The Malaysian intermodal terminal system: The implication on the Malaysian Maritime Cluster. International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy 4: 46–61.

Ouzzani, M., H. Hammady, Z. Fedorowicz, and A. Elmagarmid. 2016. Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 5 (1): 20.

Panova, Y. 2011. Potential of connecting Eurasia through Trans-Siberian Railway. International Journal of Shipping and Transport Logistics 3: 227–244.

Panova, Y., and O.-P. Hilmola. 2015. Justification and evaluation of dry port investments in Russia. Research in Transportation Economics, Austerity and Sustainable Transportation 51: 61–70.

Panova, Y., and E. Korovyakovsky. 2013. Perspective reserves of Russian seaport container terminals. World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research 4: 175–193. https://doi.org/10.1504/WRITR.2013.058979.

Qiu, X., J.S.L. Lam, and G.Q. Huang. 2015. A bilevel storage pricing model for outbound containers in a dry port system. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 73: 65–83.

Rathnayake, J., L. Jing, and A.W. Wijeratne. 2013. Dry ports: A lacuna in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Process Management and Benchmarking 3: 441–466.

Regmi, M.B., and S. Hanaoka. 2012. Assessment of intermodal transport corridors: Cases from North-East and Central Asia. Research in Transportation Business & Management, Intermodal Freight Transport and Logistics 5: 27–37.

Rodrigue, J.-P., J. Debrie, A. Fremont, and E. Gouvernal. 2010. Functions and actors of inland ports: European and North American dynamics. Journal of Transport Geography, Special Issue on Comparative North American and European gateway logistics 18: 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.03.008.

Rodrigue, J.-P., and T. Notteboom. 2012. Dry ports in European and North American intermodal rail systems: Two of a kind? Research in Transportation Business and Management 5: 4–15.

Roso, V. 2013. Sustainable intermodal transport via dry ports: Importance of directional development. World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research 4: 140–156.

Roso, V. 2009. The emergence and significance of dry ports: The case of the Port of Goteborg. World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research 2: 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1504/WRITR.2009.026209.

Roso, V. 2008. Factors influencing implementation of a dry port. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 38: 782–798.

Roso, V. 2007. Evaluation of the dry port concept from an environmental perspective: A note. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 12: 523–527.

Roso, V., and K. Lumsden. 2010. A review of dry ports. Maritime Economics & Logistics 12: 196–213.

Roso, V., D. Russell, and D. Rhoades. 2019. Diffusion of innovation assessment of adoption of the dry port concept. Transactions on Maritime Science, ToMS 8: 26–36. https://doi.org/10.7225/toms.v08.n01.003.

Roso, V., J. Woxenius, and K. Lumsden. 2009. The dry port concept: connecting container seaports with the hinterland. Journal of Transport Geography 17: 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2008.10.008.

Seuring, S., R. Wilding, and S. Gold. 2012. Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 17: 544–555.

Talley, W.K., and M. Ng. 2018. Hinterland transport chains: A behavioral examination approach. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, Making connections: Supply chain innovation research collaboration 113: 94–98.

Talley, W.K., and M. Ng. 2017. Hinterland transport chains: Determinant effects on chain choice. International Journal of Production Economics 185: 175–179.

Tranfield, D., D. Denyer, and P. Smart. 2003. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management 14: 207–222.

Veenstra, A., R. Zuidwijk, and E. Van Asperen. 2012. The extended gate concept for container terminals: Expanding the notion of dry ports. Maritime Economics and Logistics 14: 14–32. https://doi.org/10.1057/mel.2011.15.

Wang, C., Q. Chen, and R. Huang. 2018. Locating dry ports on a network: A case study on Tianjin Port. Maritime Policy & Management 45: 71–88.

Wang, G.W.Y., Q. Zeng, K. Li, and J. Yang. 2016. Port connectivity in a logistic network: The case of Bohai Bay, China. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 95: 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2016.04.009.

Werikhe, G.W., and Z.H. Jin. 2015. Integration of the extended gateway concept in supply chain disruptions management in East Africa-conceptual paper. International Journal of Engineering Research In Africa 20: 235–247.

Wilmsmeier, G., J. Monios, and B. Lambert. 2011. The directional development of intermodal freight corridors in relation to inland terminals. Journal of Transport Geography 19: 1379–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.07.010.

Witte, P., B. Wiegmans, and A.K.Y. Ng. 2019. A critical review on the evolution and development of inland port research. Journal of Transport Geography 74: 53–61.

Xie, Y., X. Liang, L. Ma, and H. Yan. 2017. Empty container management and coordination in intermodal transport. European Journal of Operational Research 257: 223–232.

Zeng, Q., M.J. Maloni, J.A. Paul, and Z. Yang. 2013. Dry port development in China: Motivations, challenges, and opportunities. Transportation Journal 52: 234–263. https://doi.org/10.1353/tnp.2013.0013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge the time and effort devoted by the MEL reviewers to improving the quality of this work. This research was funded in part by the Interreg Valu2Sea project.

Appendix

Appendix

Reviewed papers in chronological order with Scopus citations; citations marked with * are from ScienceDirect since the same were not available in Scopus

Authors | Year | Cited by | Title | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pham, H.T., Lee, H. | 2019 | 1 | Developing a Green Route Model for Dry Port Selection in Vietnam | Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics |

Wei, H., Dong, M. | 2019 | 0 | Import–export freight organization and optimization in the dry-port-based cross-border logistics network under the Belt and Road Initiative | Computers & Industrial Engineering |

Laaziz, E.H., Sbihi, N. | 2019 | 0 | A service network design model for an intermodal rail-road freight forwarder | International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management |

Facchini, F., Digiesi, S., Mossa, G. | 2019 | 2 | Optimal dry port configuration for container terminals: A non-linear model for sustainable decision making | International Journal of Production Economics |

Witte, P., Wiegmans, B., Ng, A.K.Y. | 2019 | 5 | A critical review on the evolution and development of inland port research | Journal of Transport Geography |

Digiesi, S., Facchini, F., Mummolo, G. | 2019 | 0 | Dry port as a lean and green strategy in a container terminal hub: A mathematical programming model | Management and Production Engineering Review |

Jeevan, J., Chen, S.-L., Cahoon, S. | 2019 | 2 | The impact of dry port operations on container seaports competitiveness | Maritime Policy and Management |

Nguyen, L.C., Notteboom, T. | 2019 | 2 | The relations between dry port characteristics and regional port-hinterland settings: findings for a global sample of dry ports | Maritime Policy and Management |

Hervás-Peralta, M., Poveda-Reyes, S., Molero, G.D., Santarremigia, F.E., Pastor-Ferrando, J.-P. | 2019 | 3 | Improving the performance of dry and maritime ports by increasing knowledge about the most relevant functionalities of the Terminal Operating System (TOS) | Sustainability |

Hui, F.K.P., Aye, L., Duffield, C.F. | 2019 | 1 | Engaging employees with good sustainability: Key performance indicators for dry ports | Sustainability |

Khaslavskaya, A., Roso, V. | 2019 | 4 | Outcome-Driven Supply Chain Perspectives on Dry Ports | Sustainability |

Li, W., Hilmola, O.-P., Panova, Y. | 2019 | 0 | Container sea ports and dry ports: Future CO2 emission reduction potential in China | Sustainability |

Muravev, D., Rakhmangulov, A., Hu, H., Zhou, H. | 2019 | 1 | The introduction to system dynamics approach to operational efficiency and sustainability of dry port’s main parameters | Sustainability |

Roso, V., Russell, D., Rhoades, D. | 2019 | 0 | Diffusion of Innovation Assessment of Adoption of the Dry Port Concept | Transactions on Maritime Science |

Qiu, X., Lee, C.-Y. | 2019 | 4 | Quantity discount pricing for rail transport in a dry port system | Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

Tsao, Y.-C., Thanh, V.-V. | 2019 | 3 | A multi-objective mixed robust possibilistic flexible programming approach for sustainable seaport-dry port network design under an uncertain environment | Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

Kramberger, T., Monios, J., Strubelj, G., Rupnik, B. | 2018 | 5 | Using dry ports for port co-opetition: The case of Adriatic ports | International Journal of Shipping and Transport Logistics |

Tsao, Y.-C., Linh, V.T. | 2018 | 3 | Seaport- dry port network design considering multimodal transport and carbon emissions | Journal of Cleaner Production |

Sholihah, S.A., Samadhi, T.M.A.A., Cakravastia, A., Nur Bahagia, S. | 2018 | 1 | Coordination model in hinterland chain of hub-and-spoke export trade logistics | Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management |

Jeevan, J., Chen, S.-L., Cahoon, S. | 2018 | 2 | Determining the influential factors of dry port operations: worldwide experiences and empirical evidence from Malaysia | Maritime Economics & Logistics |

Wang, C., Chen, Q., Huang, R. | 2018 | 11 | Locating dry ports on a network: a case study on Tianjin Port | Maritime Policy & Management |

Black, J., Roso, V., Marušić, E., Brnjac, N. | 2018 | 2 | Issues in dry port location and implementation in metropolitan areas: The case of Sydney, Australia | Transactions on Maritime Science |

Chang, Z., Yang, D., Wan, Y., Han, T. | 2018 | 2 | Analysis on the features of Chinese dry ports: Ownership, customs service, rail service and regional competition | Transport Policy |

Fazi, S., Roodbergen, K.J. | 2018 | 8 | Effects of demurrage and detention regimes on dry-port-based inland container transport | Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies |

Talley, W.K., Ng, M. | 2018 | 6 | Hinterland transport chains: A behavioral examination approach | Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

Zhang, Q., Wang, W., Peng, Y., Zhang, J., Guo, Z. | 2018 | 7 | A game-theoretical model of port competition on intermodal network and pricing strategy | Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

Qiu, X., Lam, J.S.L. | 2018 | 2 | The value of sharing inland transportation services in a dry port system | Transportation Science |

Komchornrit, K. | 2017 | 5 | The Selection of Dry Port Location by a Hybrid CFA-MACBETH-PROMETHEE Method: A Case Study of Southern Thailand | Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics |

Jeevan, J., Salleh, NHM., Loke, K.B., Saharuddin, A.H. | 2017 | 1* | Preparation of dry ports for a competitive environment in the container seaport system: A process benchmarking approach | International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy |

Nguyen, L.C., Notteboom, T. | 2017 | 4 | Public–private partnership model selection for dry port development: An application to Vietnam | World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research |

Oey, E., Setiawan, V. | 2017 | 2 | Evaluating import cargo performance through Tanjung Priok sea port vs. Cikarang dry port-a case study in a FMCG company in Indonesia | International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management |

Talley, W.K., Ng, M. | 2017 | 6 | Hinterland transport chains: Determinant effects on chain choice | International Journal of Production Economics |

Santos, T.A., Guedes Soares, C. | 2017 | 8 | Development dynamics of the Portuguese range as a multi-port gateway system | Journal of Transport Geography |

Wei, H., Sheng, Z. | 2017 | 4 | Dry Ports-Seaports Sustainable Logistics Network Optimization: Considering the Environment Constraints and the Concession Cooperation Relationships | Polish Maritime Research |

Notteboom, T., Yang, Z. | 2017 | 31 | Port governance in China since 2004: Institutional layering and the growing impact of broader policies | Research in Transportation Business & Management |

Roso, V., Andersson, D. | 2017 | 3 | Dry Ports and Logistics Platforms | Encyclopedia of Maritime and Offshore Engineering |

Chen, S.-L., Jeevan, J., Cahoon, S. | 2016 | 2 | Malaysian Container Seaport-Hinterland Connectivity: Status, Challenges and Strategies | Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics |

Othman, M.R., Jeevan, J., Rizal, S. | 2016 | 2* | The Malaysian Intermodal Terminal System: The Implication on the Malaysian Maritime Cluster | International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy |

Wanzala, W.G., Zhihong, J. | 2016 | 5 | Integration of the extended gateway concept in Supply Chain disruptions Management in East Africa-Conceptual paper | International Journal of Engineering Research in Africa |

Mirzabeiki, V., Roso, V., Sjöholm, P. | 2016 | 4 | Collaborative tracking and tracing applied on dry Ports | International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management |

Alam, J. | 2016 | 0 | Role of effective planning process in boosting dry port effectiveness: A case study of central Pakistan | International Journal of Supply Chain Management |

Dorostkar, E., Shahbazi, S., Naeini, S.A. | 2016 | 0 | The effect of forming dry port in spatial and regional planning system in Yazd Province | Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences |

El Hassan, L. | 2016 | 0 | Modeling framework for intermodal dry port based hinterland logistics system | Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology |

Muravev, D., Rakhmangulov, A. | 2016 | 3 | Environmental Factors’ Consideration at Industrial Transportation Organization in the « seaport-Dry port » System | Open Engineering |

Rožić, T., Rogić, K., Bajor, I. | 2016 | 4 | Research trends of inland terminals: A literature review | Promet - Traffic |

Nguyen, L.C., Notteboom, T. | 2016 | 25 | Multi-Criteria Approach to Dry Port Location in Developing Economies with Application to Vietnam | The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics |

Wang, G.W.Y., Zeng, Q., Li, K., Yang, J. | 2016 | 19 | Port connectivity in a logistic network: The case of Bohai Bay, China | Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

Awad-Núñez, S., Soler-Flores, F., González-Cancelas, N., Camarero-Orive, A. | 2016 | 1 | How should the Sustainability of the Location of Dry Ports be Measured? | Transportation Research Procedia, Transport Research Arena |

Jeevan, J., Ghaderi, H., Bandara, Y.M., Saharuddin, A.H., Othman, M.R. | 2015 | 2* | The implications of the growth of port throughput on the port capacity: the case of Malaysian major container seaports | International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy |

Li, Y., Dong, Q., Sun, S. | 2015 | 10 | Dry port development in china: Current status and future strategic directions | Journal of Coastal Research |

Fanti, M.P., Iacobellis, G., Ukovich, W., Boschian, V., Georgoulas, G., Stylios, C. | 2015 | 16 | A simulation based Decision Support System for logistics management | Journal of Computational Science |

Clott, C., Hartman, B.C., Ogard, E., Gatto, A. | 2015 | 8 | Container repositioning and agricultural commodities: Shipping soybeans by container from US hinterland to overseas markets | Research in Transportation Business & Management |

Panova, Y., Hilmola, O.-P. | 2015 | 9 | Justification and evaluation of dry port investments in Russia | Research in Transportation Economics, Austerity and Sustainable Transportation |

Bentaleb, F., Mabrouki, C., Semma, A. | 2015 | 7 | A Multi-Criteria Approach for Risk Assessment of Dry Port-Seaport System | Supply Chain Forum |

Jeevan, Jagan, Chen, S., Lee, E. | 2015 | 14 | The Challenges of Malaysian Dry Ports Development | The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics |

Chang, Z., Notteboom, T., Lu, J. | 2015 | 10 | A two-phase model for dry port location with an application to the port of Dalian in China | Transportation Planning and Technology |

Crainic, T.G., Dell’Olmo, P., Ricciardi, N., Sgalambro, A. | 2015 | 33 | Modeling dry-port-based freight distribution planning | Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, Engineering and Applied Sciences Optimization |

Qiu, X., Lam, J.S.L., Huang, G.Q. | 2015 | 14 | A bilevel storage pricing model for outbound containers in a dry port system | Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

Li, J., Jiang, B. | 2014 | 4* | Cooperation Performance Evaluation between Seaport and Dry Port; Case of Qingdao Port and Xi’an Port | International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy |

Bask, A., Roso, V., Andersson, D., Hämäläinen, E. | 2014 | 29 | Development of seaport-dry port dyads: Two cases from Northern Europe | Journal of Transport Geography |

Ambrosino, D., Sciomachen, A. | 2014 | 13* | Location of Mid-range Dry Ports in Multimodal Logistic Networks | Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences |

Awad-Núñez, S., González-Cancelas, N., Camarero-Orive, A. | 2014 | 4* | Application of a Model based on the Use of DELPHI Methodology and Multicriteria Analysis for the Assessment of the Quality of the Spanish Dry Ports Location | Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences |

Feng, X., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Wang, W. | 2013 | 9 | A Location-Allocation Model for Seaport-Dry Port System Optimization | Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society |

Rathnayake, J., Jing, L., Wijeratne, A.W. | 2013 | 2 | Dry ports: a lacuna in Sri Lanka | International Journal of Process Management and Benchmarking |

Onyemechi, C. | 2013 | 0 | Logistics Centres Assessed as a Port City Decongesting Strategy: Case Study of a Nigerian Port City | Journal of Maritime Research |

Ng, A.K.Y., Padilha, F., Pallis, A.A. | 2013 | 40 | Institutions, bureaucratic and logistical roles of dry ports: the Brazilian experiences | Journal of Transport Geography |

Onyemechi, C. | 2013 | 0 | Port efficiency modelling in the post concessioning era: The role of logistics drivers, agile ports and other perspectives | Pomorstvo |

Zeng, Q., Maloni, M.J., Paul, J.A., Yang, Z. | 2013 | 11 | Dry port development in China: Motivations, challenges, and opportunities | Transportation Journal |

Lättilä, L., Henttu, V., Hilmola, O.-P. | 2013 | 55 | Hinterland operations of sea ports do matter: Dry port usage effects on transportation costs and CO2 emissions | Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review |

Panova, Y., Korovyakovsky, E. | 2013 | 3 | Perspective reserves of Russian seaport container terminals | World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research |

Roso, V. | 2013 | 24 | Sustainable intermodal transport via dry ports–importance of directional development | World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research |

Beresford, A., Pettit, S., Xu, Q., Williams, S. | 2012 | 55 | A study of dry port development in China | Maritime Economics & Logistics |

Padilha, F., Ng, A.K. | 2012 | 31 | The spatial evolution of dry ports in developing economies: The Brazilian experience | Maritime Economics & Logistics |

Haralambides, H., Gujar, G. | 2012 | 34 | On balancing supply chain efficiency and environmental impacts: An eco-DEA model applied to the dry port sector of India | Maritime Economics and Logistics |

Veenstra, A., Zuidwijk, R., Van Asperen, E. | 2012 | 83 | The extended gate concept for container terminals: Expanding the notion of dry ports | Maritime Economics and Logistics |

Monios, J., Wilmsmeier, G. | 2012 | 53 | Port-centric logistics, dry ports and offshore logistics hubs: strategies to overcome double peripherality? | Maritime Policy and Management |

Ng, A.K.Y., Cetin, I.B. | 2012 | 36 | Locational Characteristics of Dry Ports in Developing Economies: Some Lessons from Northern India | Regional Studies |

Regmi, M.B., Hanaoka, S. | 2012 | 21 | Assessment of intermodal transport corridors: Cases from North-East and Central Asia | Research in Transportation Business & Management |

Rodrigue, J.-P., Notteboom, T. | 2012 | 43 | Dry ports in European and North American intermodal rail systems: Two of a kind? | Research in Transportation Business and Management |

Ambrosino, D., Sciomachen, A. | 2012 | 3 | How to reduce the impact of container flows generated by a maritime terminal on urban transport | WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment |

Hanaoka, S., Regmi, M.B. | 2011 | 50 | Promoting intermodal freight transport through the development of dry ports in Asia: An environmental perspective | IATSS Research |

Ka, B. | 2011 | 42 | Application of fuzzy AHP and ELECTRE to China dry port location selection | Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics |

Panova, Y. | 2011 | 9 | Potential of connecting Eurasia through Trans-Siberian Railway | International Journal of Shipping and Transport Logistics |

Wilmsmeier, G., Monios, J., Lambert, B. | 2011 | 73 | The directional development of intermodal freight corridors in relation to inland terminals | Journal of Transport Geography |

Dadvar, E., Ganji, S.R.S., Tanzifi, M. | 2011 | 4 | Feasibility of establishment of “Dry Ports” in the developing countries-the case of Iran | Journal of Transportation Security |

Do, N.-H., Nam, K.-C., Le, Q.-L.N. | 2011 | 12 | A consideration for developing a dry port system in Indochina area | Maritime Policy and Management |

Haralambides, H., Gujar, G. | 2011 | 20 | The Indian dry ports sector, pricing policies and opportunities for public–private partnerships | Research in Transportation Economics |

Korovyakovsky, E., Panova, Y. | 2011 | 16 | Dynamics of Russian dry ports | Research in Transportation Economics |

Flämig, H., Hesse, M. | 2011 | 28 | Placing dryports. Port regionalization as a planning challenge – The case of Hamburg, Germany, and the Süderelbe | Research in Transportation Economics |

Henttu, V., Hilmola, O.-P. | 2011 | 28 | Financial and environmental impacts of hypothetical Finnish dry port structure | Research in Transportation Economics |

Monios, J. | 2011 | 40 | The role of inland terminal development in the hinterland access strategies of Spanish ports | Research in Transportation Economics |

Henttu, V., Lättilä, L., Hilmola, O.-P. | 2011 | 7 | Optimization of relative transport costs of a hypothetical dry port structure | Transport and Telecommunication |

Rodrigue, J.-P., Debrie, J., Fremont, A., Gouvernal, E. | 2010 | 125 | Functions and actors of inland ports: European and North American dynamics | Journal of Transport Geography, Special Issue |

Ng, A.K., Tongzon, J.L. | 2010 | 22 | The transportation sector of India’s economy: dry ports as catalysts for regional development | Eurasian Geography and Economics |

Roso, V., Lumsden, K. | 2010 | 63 | A review of dry ports | Maritime Economics & Logistics |

Ng, K.Y.A., Gujar, G.C. | 2009 | 63 | The spatial characteristics of inland transport hubs: evidences from Southern India | Journal of Transport Geography |

Roso, V., Woxenius, J., Lumsden, K. | 2009 | 221 | The dry port concept: connecting container seaports with the hinterland | Journal of Transport Geography |

Ng, AdolfK.Y., Gujar, G.C. | 2009 | 47 | Government policies, efficiency and competitiveness: The case of dry ports in India | Transport Policy |

Roso, V. | 2009 | 15 | The emergence and significance of dry ports: The case of the Port of Goteborg | World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research |

Roso, V. | 2008 | 62 | Factors influencing implementation of a dry port | International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management |

Jaržemskis, A., Vasiliauskas, A.V. | 2007 | 51 | Research on dry port concept as intermodal node | Transport |

Roso, V. | 2007 | 81 | Evaluation of the dry port concept from an environmental perspective: A note | Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khaslavskaya, A., Roso, V. Dry ports: research outcomes, trends, and future implications. Marit Econ Logist 22, 265–292 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-020-00152-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41278-020-00152-9