Abstract

One of the explanations for global imbalances is the self-financing behavior of credit-constrained firms in rapidly growing emerging markets. The paper uses an extensive firm-level data set from several Asian countries during 2002–11, and tests the micro foundation of this theory by estimating the effect of an exogenous change in credit constraints, resulting from financial reforms, on firms’ saving behavior. As predicted, after financial reforms, firms who were credit constrained previously decreased their savings more (or increased their savings less) relative to unconstrained firms. However, this firm-level effect did not lead to a decrease in aggregate corporate savings as conjectured by the theory. The sector-level regressions show that corporate savings increased after financial reforms, and more so for sectors more dependent on external finance. The current account surpluses also did not register a significant deterioration after financial reforms, consistent with the paper’s findings on sectoral and aggregate corporate savings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Relatedly, Sandri (2014) shows that the precautionary motive of entrepreneurs can explain capital outflow during the growth acceleration period; Bacchetta and Benhima (2015) show that, in a model with liquidity constraint, the demand for liquid foreign bond is complement to domestic investment, and this complementarity could explain capital outflows from fast-growing emerging economies.

See Kalemli-Özcan and others (2015) for details on the data including coverage and representation.

The other set of countries where we can do a similar decomposition in the ownership structure is Latin America, but most of the financial reforms are much earlier than 2000s and hence we cannot measure the change in credit constraints during our sample period for firm-level data in a comparable way to the Asian countries.

The data are originally constructed by Abiad and Mody (2005) and extended by Abiad, Detragiache, and Tressel (2010) to cover more countries and longer periods.

All our countries undertook several financial reforms during 2002–05, and the specific years are as follows: China, 2002 and 2004; India, 2004; Indonesia, 2003; Malaysia, 2003, 2004; Philippines, 2005; Taiwan, 2002, 2003; and Thailand, 2003. Reforms in this database are direct measures to reduce financial frictions such as removal of interest rate control and security market reform.

Thailand’s reform is a reversal, so it caused an increase in credit constraints; Taiwan reversed its private ownership reform in 2002 one year later.

Song, Storesletten, and Zilibotti (2011), using data from China National Bureau of Statistics Flow of Funds, show that profits, return to capital, and employment are higher and rising in private firms compared with SOEs since 1998. Dollar and Wei (2007), using detailed survey data on 12,400 firms, though for a single year of 2005, also show average return to capital to be twice as high in private firms as in fully state-owned enterprises. SOEs have also been documented to have easier access to bank loans, even many years after the market-oriented reforms (see, for example, Cull and Xu, 2003; Song, Storesletten, and Zilibotti, 2011; Dollar and Wei, 2007, among many others).

In this paper, we do not attempt to look into what are the distortions that help SOEs sustain their low productivity or better access to external finance, but rather provide empirically sound estimates of an exogenous removal of certain distortions, that is, credit constraints, on the differences between savings of firms that were credit-constrained and savings of firms that were not before the reform.

See, for example, Li (1997) and reference thereto.

The differences between Columns 4 and 5 might be due to statistical discrepancies or small differences in time horizon.

See Kalemli-Özcan and others (2015) on how to get good coverage and representation out of the ORBIS data in general.

During this period, Japan, Hong Kong, Korea, and Singapore, all of which are in our sample, experienced no financial reforms, and they will act as control groups in the differences-in-differences estimation.

Formally, Dependence=(Capital Expenditures−Cash Flow From Operations)/(Capital Expenditures).

However, we verify when including lagged investment rate as control, the result is qualitatively similar.

Using sales growth, another imperfect but commonly used measure, gives us identical results.

Specifically, we aggregate total assets and “Other Shareholders’ Fund” over firms in each two-digit industry, and then construct a measure of savings rate analogous to Savings1. In this aggregation, to keep the composition of sector fixed we focus on the sample of continuing firms. We winsorize the sample at top and bottom 2 percent to rule out the influence of outliers; the results are robust to trimming and winsorization choices.

Figure 2 simply plots the aggregate OSHF for all firms classified as SOE and non-SOEs, with their values for the first year normalized to 1. To rule out composition change we focus on the sample of continuing firms, but the same pattern exists for the full sample.

The correlation between the two measures is 0.45. The standard deviation for the two measures are 1.28 (U.S.-based measure) and 0.51 (our sample).

References

Abiad, Abdul and Ashoka Mody, 2005, “Financial Reform: What Shakes It? What Shapes It?,” American Economic Review, Vol. 95, No. 1, pp. 66–88.

Abiad, Abdul G., Enrica Detragiache, and Thierry Tressel, 2010, “A New Database of Financial Reforms,” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 57, No. 2, pp. 281–302.

Aguiar, Mark and Manuel Amador, 2011, “Growth in the Shadow of Expropriation,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 126, No. 2, pp. 651–97.

Alfaro, Laura, Şebnem Kalemli-Özcan, and Vadym Volosovych, 2014, “Sovereigns, Upstream Capital Flows, and Global Imbalances,” Journal of European Economic Association, Vol. 12, No. 5, pp. 1240–84.

Bacchetta, Philippe and Kenza Benhima, 2015, “The Demand for Liquid Assets, Corporate Saving, and International Capital Flows,” Journal of the European Economic Association, advance online publication, May 8, 2015; doi: 10.1111/jeea.12132.

Bayoumi, Tamim, Hui Tong, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2012, “The Chinese Corporate Savings Puzzle: A Firm-level Cross-country Perspective,” in Capitalizing China, ed. by Joseph P.H. Fan, and Randall Morck (University of Chicago Press), pp. 283–308.

Benigno, Gianluca and Luca Fornaro, 2012, “Reserve Accumulation, Growth and Financial Crises,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 9224.

Buera, Francisco J. and Yongseok Shin, 2009, “Productivity Growth and Capital Flows: The Dynamics of Reforms,” NBER Working Paper No. 15268.

Caballero, Ricardo J., Emmanuel Farhi, and Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, 2008, “An Equilibrium Model of ‘Global Imbalances’ and Low Interest Rates,” American Economic Review, Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 358–93.

Chamon, Marcos D. and Eswar S. Prasad, 2010, “Why Are Saving Rates of Urban Households in China Rising?,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 93–130.

Chamon, Marcos, Kai Liu, and Eswar S Prasad, 2010, “Income Uncertainty and Household Savings in China,” NBER Working Paper No. 16565.

Choukhmane, Taha, Nicolas Coeurdacier, and Keyu Jin, 2013, “The One-Child Policy and Household Savings in China,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 9688.

Cull, Robert and Lixin Colin Xu, 2003, “Who Gets Credit? The Behavior of Bureaucrats and State Banks in Allocating Credit to Chinese State-Owned Enterprises,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 71, No. 2, pp. 533–59.

Dollar, David and Shang-Jin Wei, 2007, “Das (Wasted) Kapital: Firm Ownership and Investment Efficiency in China,” NBER Working Paper No. 13103.

Dooley, Michael P., David Folkerts-Landau, and Peter Garber, 2007, “Direct Investment, Rising Real Wages and the Absorption of Excess Labor in the Periphery,” in G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, ed. by Richard H. Clarida (University of Chicago Press), pp. 103–132.

Du, Qingyuan and Shang-Jin Wei, 2013, “A Theory of the Competitive Saving Motive,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 91, No. 2, pp. 275–89.

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier and Olivier Jeanne, 2013, “Capital Flows to Developing Countries: The Allocation Puzzle,” The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 80, No. 4, pp. 1484–515.

Kalemli-Özcan, Şebnem and others, 2015, “How to Construct Nationally Representative Firm Level Data from the ORBIS Global Database,” NBER Working Paper No. 21558.

Karabarbounis, Loukas and Brent Neiman, 2014, “The Global Decline of the Labor Share,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 129, No. 1, pp. 61–103.

Kuijs, Louis, 2006, “How Will China’s Saving-Investment Balance Evolve?,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3958.

Li, Wei, 1997, “The Impact of Economic Reform on the Performance of Chinese State Enterprises, 1980–1989,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 105, No. 5, pp. 1080–106.

Mendoza, Enrique G, Vincenzo Quadrini, and José-Víctor Ríos-Rull, 2009, “Financial Integration, Financial Development, and Global Imbalances,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 117, No. 3, pp. 371–416.

Rajan, Raghuram G. and Luigi Zingales, 1998, “Financial Dependence and Growth,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 88, No. 3, pp. 559–86.

Sandri, Damiano, 2014, “Growth and Capital Flows with Risky Entrepreneurship,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 102–23.

Song, Zheng and Dennis Tao Yang, 2010, “Life Cycle Earnings and Saving in a Fastgrowing Economy” (unpublished; Chinese University of Hong Kong).

Song, Zheng, Kjetil Storesletten, and Fabrizio Zilibotti, 2011, “Growing Like China,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 1, pp. 196–233.

Wei, Shang-Jin and Xiaobo Zhang, 2011, “The Competitive Saving Motive: Evidence from Rising Sex Ratios and Savings Rates in China,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 119, No. 3, pp. 511–64.

Yang, Dennis Tao, 2012, “Aggregate Savings and External Imbalances in China,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 125–46.

Yang, Dennis Tao, Junsen Zhang, and Shaojie Zhou, 2011, “Why Are Saving Rates so High in China?,” in Capitalizing China, ed. by Joseph P.H. Fan, and Randall Morck (University of Chicago Press), pp. 249–78.

Additional information

Supplementary information accompanies this article on the IMF Economic Review website (www.palgrave-journals.com/imfer).

This paper was prepared for the IMF Economic Review-Bank of Korea Conference 2013.

*Jingting Fan is a graduate student in economics at the University of Maryland. Şebnem Kalemli-Özcan is Neil Moskowitz Endowed Professor of Economics at University of Maryland, College Park. She is a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and a Research Fellow at the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). The authors thank the editor Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, two anonymous referees, their discussant Markus Bruckner, and the conference participants for their comments. Thanks are due to Alberto Martin for helpful discussions.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix

Appendix

Data Appendix

Firm-Level Data

Data Preparations

Our firm-level financial information is obtained in the “Global Detailed Form” (for listed companies), and the “Global Standard Form” (for private companies), from the ORBIS database. For listed companies, the financial information include all detailed items on the balance sheet and the profit/loss accounts. For private companies, the information is coarser.

For the majority of companies in our sample, the financial information is from December of each year. Some companies, however, report their financial information in other months. For the companies whose financial information are from months before June, we change the year of information to the year before the time of report. For example, if a company reports a profit of 1 million in May, 2013, we count this as its profit for the year of 2012.

There is enormous heterogeneity in the firm-level variables. To prevent outliers from affecting our analysis, in all our firm-level regression analysis, we trim our dependent variables at 2 percent from both the top and the bottom. A 2 percent trimming makes the distributions of dependent variables look approximately normal. Although not reported here, for robustness, we also try winsorizing the outliers, and the results are robust. The descriptive statistics in Table 5 is based on the sample after trimming and dropping the observations for which we do not have ownership information. We also further exclude public administrations, finance, and other service industries in both computing descriptive statistics and performing regression analysis.

Constructing the State Ownership Status

We proceed as follows to classify the ownership status of the firms in our sample.

First, we find companies whose global ultimate owner is recorded in the BvD Ownership Database. In extracting the information, we require a minimum of 25 percent shares along each link. We generate SOE1 based on the type of this ultimate owner: if a company’s ultimate owner is recorded as “public authority, government,” we assign a value of 1 to this variable; otherwise we assign a value of 0 to it. In the case where a company’s ultimate owner is missing, or the type of the ultimate owner is unclear, we leave SOE1 with missing value.

Second, we use the information from Step 1 to update the type of each company’s shareholders. Therefore, if Company B—a shareholder of Company A—has an ultimate owner being “Public Authority,” we change the type of Company B to “Public Authority” as well, even though B itself might be an “Industry Company” or “Financial Company.” This procedure serves to capture to the maximum extent the possibility that government authorities may hold companies indirectly through either industry company, financial companies or other type of entities. In this case, the ownership goes as Government-B-A, and B is the intermediary through which the government control A, so we update B’s type to “Public Authority.”

Third, we also create SOE2, and set this variable to 1, if firm’s biggest direct shareholder in a given year is recorded as “Public Authority.” The difference here is that this dummy is based on direct shareholder, whereas the previous SOE1 is based on ultimate ownership. The shareholder data are in principle by firm-year, but there is limited over-time variation in ownership status. We use shareholder information from the last year of the sample and fix the ownership status for each firm for the entire sample period. This also prevents endogenous change in ownership as a response to financial reforms.

Finally, we determine firms’ type based on SOE1 and SOE2. As we are more confident in SOE1, when the two dummies differ, we use SOE1. In a robustness check we run regression with SOE2 only, and our results do not change.

Measure for External Finance Dependence

We construct the Rajan-Zingales measure for industry-level external finance dependence using two different samples.

The first measure is generated using a sample of U.S. listed companies. We focus on Compustat North America database, and extract all observations between 1990 and 1999. We aggregate firm-level capital expenditures and cash flows from operations over the 10 years to flush out yearly fluctuations, and use that to generate firm-level dependence on external finance, following the formula:

We take the median of this value for each industry, dropping industries with only one firm, and use this median value as our first measure of industry external finance dependence.

The second measure is generated using our own sample of firms. To capture the technological frontier in our sample of countries, we focus on the listed companies, as those are with best access to finance in any given industry. To rule out sectoral difference in representativeness from firms’ entry into and exit from the database, which not necessarily reflect firms’ entry and exit decisions, and the influence of the global financial crisis, we restrict to the sample of continuing firms for the before-crisis period. We then use the resulting sample to first aggregate over time for each firm to construct firm-level dependence, and then take median value for each industry to arrive at the industry-level measure for external finance dependence. An industry is defined as an SIC two-digit sector in constructing both measures, consistent with industry classifications in our regression analysis.

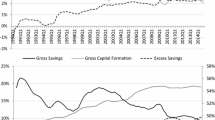

National Accounts Data

Our aggregate data on national accounts (Figure 1 and Table 1) are extracted from the World Economic Outlook Database from the IMF. The savings and investment data by sector (Table 3) are collected from flows-of-funds table of the sample countries. A detailed description is provided in the supplementary material.