Abstract

This article aims to explain why, despite the fact that all national competition authorities (NCAs) in EU member states enforce the same law, relevant differences exist in the degree of independence that these agencies enjoy. The author advances an original theoretical framework according to which the decision on the independence of NCAs depends on the structure of the economic system of a country. In particular, it is hypothesized that the means by which firms operate in the national market affects the tendency of national legislators to delegate more or less independence to the NCA. The statistical analysis carried out shows that both countries with low and high levels of employer density tend to have less independent competition authorities than those of other countries. On the one hand, the findings support the argument, advanced by varieties-of-capitalism scholars, that liberal market economies and coordinated market economies achieve greater efficiency than mixed market economies. On the other, the expectation that all institutional choices should be coherent with the firms’ coordination method is not confirmed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

‘Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 of 21 December 1989 on the control of concentrations between undertakings’.

EC Regulation 1/2003 prescribes that all the European competition authorities have to implement Articles 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which prohibit agreements restricting competition and abuses of dominant position.

See, in particular, Article 3 of Regulation 1/2003.

If

and A=f(B), then:If ∀ Ai:A i =A i, then ∀ B j :B j= B j .

In this article, by the terms ‘legislators’, ‘lawmakers’ and ‘politicians’, I will refer to members both of the parliament and of the government. As a matter of fact, especially in the countries studied here, it is impossible to attribute political decisions either to one body or to the other: in all the EU member states (except Cyprus), the government must have the confidence of the parliament, and distinguishing between the two makes little sense.

As Koop (2011) has shown, regulatory agencies are more accountable (that is, less independent) in highly salient policy fields.

The survey, collected between September and December 2009, was mainly based on Gilardi’s (2002; 2005a) one, which was drawn from that of Cukierman et al (1992). Some adjustments were also suggested by Hanretty and Koop (2012).

The problems connected with the assumptions often made to construct these indices are discussed by Hanretty and Koop (2012). The factor analysis method, like all the others employed by other scholars, assumes that independence is unidimensional throughout the data. The index employed in the statistical analysis and another calculated with Gilardi’s method are correlated at 89 per cent.

Factor analysis has been performed on a data set including all the variables drawn from the survey, using the principal-component factor method. As there were some missing values (and factor analysis by default deletes all the observations with missing values), I needed to impute them using multiple imputation. The original data set contained 99 missing values out of 1053 values (9 per cent). However, it must be considered that eight authorities had nine missing values each because they do not have a board − therefore they could not answer the questions of the survey which regarded the board. If we exclude these 72 ‘inevitable’ missing values, the missing values due to a lack of answer were only 27 (2.5 per cent). The Multiple Imputation command (in PASW 18) has generated five imputed data sets. To obtain the matrix for factor analysis, I have calculated the mean across these five replications for every value in the data sets.

This database was used because it contains data on all the EU member states – a requirement for this analysis.

For some countries, yearly data are not available. However, there is very little variation across time (the average coefficient of variation is very low, 0.04) among all cases. Therefore, missing values are little likely to bias the calculated mean value.

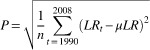

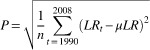

The polarization value for each country is the standard deviation of this distribution, calculated with the formula:

where LR t is the left–right value, in a scale going from 0 (maximum left) to 10 (maximum right), for each country in year t;μLR is the mean of this value across the period of interest.n is the number of years included in the calculation.The left–right position of each country’s government for each year has been calculated as:

where S x is the number of seats that party x holds in the parliament in year t;LR x is the left–right position of that party;n is the number of the parties supporting the government in year t.All the data for these indicators have been taken from the ParlGov database (http://www.parlgov.org) (Doering and Manow, 2010). The polarization index is a component of the ‘replacement risk’ indicator developed by Franzese (2002).

The studentized Breusch–Pagan test (Breusch and Pagan, 1979; Zeileis and Hothorn, 2002) reports a statistic of 5.10 with 5 degrees of freedom, which is significant at 0.32.

The Bonferroni outlier test (Fox and Weisberg, 2011) does not indicate the presence of any P-value lower than 0.05 (the smaller Bonferroni P-value is 0.75).

The graph in Figure 2 has been obtained by simulating expected values and standard deviation for each permille of the employer density’s distribution (10 000 simulations for each permille). Simulations have been performed with the programme Zelig (Imai et al, 2009) in R (R Core Team, 2012). For a discussion of the logic and the advantages of simulation over other post-estimation methods, see King et al (2000).

The code for the graph in Figure 3 has been taken from one of the examples presented by Kastellec and Leoni (2007).

Bootstrapped simulations have been performed with the programme Zelig (Imai et al, 2009) in R (R Core Team, 2012).

For the employer density indicator, the three values have been set, respectively, to the 5th, the 50th and the 95th percentile (0.22, 0.6, 0.85). For polarization, the two values have been set at the 5th and 95th percentile (0.45, 2.01). For EU membership, the three values have been set at the minimum, the mean and the maximum (2, 23, 57).

References

Allen, M. (2004) The varieties of capitalism paradigm: Not enough variety? Socio-Economic Review 2 (1): 87–108.

Amato, G. (1997) Antitrust and the Bounds of Power: The Dilemma of Liberal Democracy in the History of the Market. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Barro, R.J. and Gordon, D.B. (1983) Rules, discretion and reputation in a model of monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics 12 (1): 101–121.

Bawn, K. (1995) Political control versus expertise: Congressional choices about administrative procedures. The American Political Science Review 89 (1): 62–73.

Börzel, T.A. and Risse, T. (2003) Conceptualizing the domestic impact of Europe. In: K. Featherstone and C.M. Radaelli (eds.) The Politics of Europeanization. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 57–82.

Breusch, T.S. and Pagan, A.R. (1979) A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica 47 (5): 1287–1294.

Brinegar, A., Jolly, S. and Kitschelt, H. (2004) Varieties of capitalism and political divides over European integration. In: G. Marks and M. Steenbergen (eds.) European Integration and Political Conflict. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 62–89.

Checkel, J.T. (2005) International institutions and socialization in Europe: Introduction and framework. International Organization 59 (4): 801–826.

Cini, M. and McGowan, L. (1998) Competition Policy in the European Union. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cukierman, A., Webb, S.B. and Neyapti, B. (1992) Measuring the independence of central banks and its effect on policy outcomes. The World Bank Economic Review 6 (3): 353–398.

Doering, H. and Manow, P. (2010) Parliament and government composition database (ParlGov): An infrastructure for empirical information on political institutions – Version 10/02.

Elgie, R. and McMenamin, I. (2005) Credible commitment, political uncertainty or policy complexity? Explaining variations in the independence of non-majoritarian institutions in France. British Journal of Political Science 35 (3): 531–548.

Estevez-Abe, M. (2005) Gender bias in skills and social policies: The varieties of capitalism perspective on sex segregation. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender: State & Society 12 (2): 180–215.

Fiorina, M.P. (1982) Legislative choice of regulatory forms: Legal process or administrative process? Public Choice 39 (1): 33–66.

Fox, J. and Weisberg, S. (2011) An R Companion to Applied Regression, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Franchino, F. (2002) Efficiency or credibility? Testing the two logics of delegation to the European commission. Journal of European Public Policy 9 (5): 677–694.

Franzese, R.J. (2002) Macroeconomic Policies of Developed Democracies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Frye, T. (2002) The perils of polarization: Economic performance in the postcommunist world. World Politics 54 (3): 308–337.

Frye, T. (2010) Building States and Markets after Communism: The Perils of Polarized Democracy. Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Gilardi, F. (2002) Policy credibility and delegation to independent regulatory agencies: A comparative empirical analysis. Journal of European Public Policy 9 (6): 873–893.

Gilardi, F. (2005a) The formal independence of regulators: A comparison of 17 countries and 7 sectors. Swiss Political Science Review 11 (4): 139–167.

Gilardi, F. (2005b) The institutional foundations of regulatory capitalism: The diffusion of independent regulatory agencies in Western Europe. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 598 (1): 84–101.

Guardiancich, I. and Orenstein, M. (2012) Patronage or policy stability in East European Welfare States. Paper prepared for the 2012 APSA Annual Meeting: Representation and Renewal; 30 August–2 September, New Orleans.

Hall, P.A. and Gingerich, D.W. (2009) Varieties of capitalism and institutional complementarities in the political economy: An empirical analysis. British Journal of Political Science 39 (3): 449–482.

Hall, P.A. and Soskice, D. (eds.) (2001a) An introduction to varieties of capitalism. In: Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford, England; New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–68.

Hall, P.A. and Soskice, D. (eds.) (2001b) Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford, England; New York: Oxford University Press.

Hancké, B., Rhodes, M. and Thatcher, M. (eds.) (2007a) Introduction: Beyond varieties of capitalism. In: Beyond Varieties of Capitalism: Conflict, Contradiction, and Complementarities in the European Economy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–38.

Hancké, B., Rhodes, M. and Thatcher, M. (eds.) (2007b) Beyond Varieties of Capitalism: Conflict, Contradiction, and Complementarities in the European Economy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hanretty, C. and Koop, C. (2012) Measuring the formal independence of regulatory agencies. Journal of European Public Policy 19 (2): 198–216.

Héritier, A. (1997) Market-making policy in Europe: Its impact on member state policies. The case of road haulage in Britain, the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. Journal of European Public Policy 4 (4): 539–555.

Howell, C. (2003) Varieties of capitalism: And then there was one? Comparative Politics 36 (1): 103–124.

Imai, K., King, G. and Lau, O. (2009) Zelig: Everyone’s Statistical Software, Version 3.5.4, [online] http://gking.harvard.edu/zelig.

Jordana, J. and Levi-Faur, D. (2005) The diffusion of regulatory capitalism in Latin America: Sectoral and national channels in the making of a new order. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 598: 102–124.

Karagiannis, Y. (2010) Collegiality and the politics of European competition policy. European Union Politics 11 (1): 143–164.

Kassim, H. (2003) Meeting the demands of EU membership: The Europeanization of national administrative systems. In: K. Featherstone and C. Radaelli (eds.) The Politics of Europeanization. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 83–111.

Kassim, H. and Wright, K. (2009) Bringing regulatory processes back in: The reform of EU antitrust and merger control. West European Politics 32 (4): 738–755.

Kastellec, J.P. and Leoni, E.L. (2007) Using graphs instead of tables in political science. Perspectives on Politics 5 (4): 755–771.

King, G., Tomz, M. and Wittenberg, J. (2000) Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science 44 (2): 347–361.

Koop, C. (2011) Explaining the accountability of independent agencies: The importance of political salience. Journal of Public Policy 31 (2): 209–234.

Kydland, F.E. and Prescott, E.C. (1977) Rules rather than discretion: The inconsistency of optimal plans. The Journal of Political Economy 85 (3): 473–491.

Lee, C.K. and Strang, D. (2006) The international diffusion of public-sector downsizing: Network emulation and theory-driven learning. International Organization 60 (4): 883–909.

Levi-Faur, D. (2004) On the ‘net impact’ of Europeanization: The EU’s telecoms and electricity regimes between the global and the national. Comparative Political Studies 37 (1): 3–29.

Levi-Faur, D. (2005) The global diffusion of regulatory capitalism. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 598 (1): 12–32.

Lewis, J. (2005) The Janus face of Brussels: Socialization and everyday decision making in the European Union. International Organization 59 (4): 937–971.

Majone, G. (1994) The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics 17 (3): 77–101.

Majone, G. (1996) Temporal Consistency and Policy Credibility: Why Democracies Need Non-Majoritarian Institutions. EUI Working Papers, RSCAS 1996/57, Florence: European University Institute.

McCubbins, M.D., Noll, R.G. and Weingast, B.R. (1987) Administrative procedures as instruments of political control. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 3 (2): 243–277.

McCubbins, M.D. and Schwartz, T. (1984) Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms. American Journal of Political Science 28 (1): 165–179.

McGowan, L. (2005) Europeanization unleashed and rebounding: Assessing the modernization of EU cartel policy. Journal of European Public Policy 12 (6): 986–1004.

McGowan, L. and Wilks, S. (1995) The first supranational policy in the European Union: Competition policy. European Journal of Political Research 28 (2): 141–169.

McNamara, K.R. (2002) Rational fictions: Central bank independence and the social logic of delegation. West European Politics 25 (1): 47–76.

Miller, G.J. (2005) The political evolution of principal-agent models. Annual Review of Political Science 8 (1): 203–225.

Moe, T.M. (1990) Political institutions: The neglected side of the story. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 6 (Special Issue): 213–253.

Molina, O. and Rhodes, M. (2007) The political economy of adjustment in mixed market economies: A study of Spain and Italy. In: B. Hancké, M. Rhodes and M. Thatcher (eds.) Beyond Varieties of Capitalism: Conflict, Contradictions and Complementarities in the European Economy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 223–252.

Mykhnenko, V. (2007) Strengths and weaknesses of weak coordination: Economic institutions, revealed comparative advantages, and socio-economic performance of mixed market economies in Poland and Ukraine. In: B. Hancké, M. Rhodes and M. Thatcher (eds.) Beyond Varieties of Capitalism: Conflict, Contradiction, and Complementarities in the European Economy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 351–378.

OECD. (2002) Regulatory policies in OECD countries, [online] http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/regulatory-policies-in-oecd-countries_9789264177437-en, accessed 20 January 2012.

Peritz, R.J.R. (1990) Foreword: Antitrust as public interest law. New York Law School Law Review 35 (4): 767–790.

R Core Team. (2012) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Radaelli, C. (2008) Europeanization, policy learning, and new modes of governance. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 10 (3): 239–254.

Rogoff, K. (1985) The optimal degree of commitment to an intermediate monetary target. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 100 (4): 1169–1189.

Ross, S.A. (1973) The economic theory of agency: The principal’s problem. The American Economic Review 63 (2): 134–139.

Schmidt, V.A. (2001) Europeanization and the mechanics of economic policy adjustment. Journal of European Public Policy 9 (6): 894–912.

Schmidt, V.A. (2009) Putting the political back into political economy by bringing the state back in yet again. World Politics 61 (3): 516–546.

Thatcher, M. (2007) Reforming national regulatory institutions: The EU and cross-national variety in European network industries. In: B. Hancké, M. Rhodes and M. Thatcher (eds.) Beyond Varieties of Capitalism: Conflict, Contradiction, and Complementarities in the European Economy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 147–172.

Thatcher, M. and Stone Sweet, A. (2002) Theory and practice of delegation to non-majoritarian institutions. West European Politics 25 (1): 1–22.

Visser, J. (2011) ICTWSS: Database on Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention and Social Pacts in 34 countries between 1960 and 2007, Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies. http://www.uva-aias.net/208, accessed 30 October 2012.

Vogel, S.K. (1996) Freer Markets, More Rules: Regulatory Reform in Advanced Industrial Countries. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Watson, M. (2003) Ricardian political economy and the ‘varieties of capitalism’ approach: Specialization, trade and comparative institutional advantage. Comparative European Politics 1 (2): 227–240.

Weingast, B.R. and Moran, M.J. (1983) Bureaucratic discretion or congressional control? Regulatory policymaking by the federal trade commission. The Journal of Political Economy 91 (5): 765–800.

Wilks, S. and Bartle, I. (2002) The unanticipated consequences of creating independent competition agencies. West European Politics 25 (1): 148–172.

Wilks, S. and McGowan, L. (1995) Disarming the commission: The debate over a European cartel office. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 33 (2): 259–273.

Wilks, S. and McGowan, L. (1996) Competition policy in the European union: Creating a federal agency? In: G.B. Doern and S. Wilks (eds.) Comparative Competition Policy: National Institutions in a Global Market. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 225–267.

Wonka, A. and Rittberger, B. (2010) Credibility, complexity and uncertainty: Explaining the institutional independence of 29 EU agencies. West European Politics 33 (4): 730–752.

Zeileis, A. and Hothorn, T. (2002) Diagnostic checking in regression relationships. R News 2 (3): 7–10.

Acknowledgements

The author wants to thank Adrienne Héritier, Yannis Karagiannis, Igor Guardiancich and three anonymous CEP reviewers for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guidi, M. Delegation and varieties of capitalism: Explaining the independence of national competition agencies in the European Union. Comp Eur Polit 12, 343–365 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2013.6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2013.6