Abstract

Even during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic health professionals were facing mental health challenges. The aim of this study was to examine the mental health of doctors, nurses and other professional groups in Europe and to identify differences between the professional groups. We conducted a cross-sectional online survey in 8 European countries. We asked for demographic data, whether the participants were exposed to COVID-19 at work, for main information sources about the pandemic, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21), and major stressors. A MANCOVA was carried out to find predictors of mental health among health care professionals. The sample (N = 1398) consisted of 237 physicians, 459 nurses, and 351 other healthcare professionals and 351 non-medical professionals with no direct involvement in patient care. The mean mental health of all groups was affected to a mild degree. Major predictors for depression and anxiety were the profession group with higher scores especially in the group of the nurses and working directly with COVID-patients. In the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the psychological burden on health professionals has remained high, with being nurse and working directly with COVID19 patients being particular risk factors for mental distress. We found as a main result that nurses scored significantly higher on depression and anxiety than practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Background

After more than 3 years, the burden of disease in the general population due to the COVID-19 pandemic remains very high, with a total of over half a billion confirmed cases and more than 6 million deaths concerning COVID-191. Calculations of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) with a loss of 305,641 life years in Germany2 and 30,181 life years in Denmark3 even more emphasize the severe consequences of COVID-19 in the European population. Various protective measures such as lockdowns, social distancing regulations, or vaccinations were imposed to contain the medical consequences4, however an end of the Covid-19 impact is not in sight. This high burden of disease also places a particularly high burden on the health systems and, in association, on the mental health of health care professionals5,6. Although there is no compelling evidence that the impact of the pandemic on mental health was more pronounced in health care professionals than in the general population7,8, there is considerable heterogeneity in this matter and much remains to be studied with regards to the identification of specific risk factors in this population.

Much research so far has been done on the people who work in the health system and their mental distress. For example, in April 2020 numerous professionals in the health system in Spain showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders, and depression, with women and younger people showing an increased risk9. A Portuguese study among physicians in 2020 showed that working directly with patients with COVID-19 also led to more symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety, with female physicians being particularly affected10. A follow-up study over a year showed a significant decrease in stress and depression values, but the authors found a prospective connection between depression, stress, and symptoms of a post-traumatic stress disorder. Moreover, the female gender, but also the fear of being infected or infecting people close to them, and the reported insufficient access to protective material were identified as risk factors11. A higher burden on nurses in comparison to the physicians could be demonstrated in multiple studies9,12,13,14,15.

In addition to the professional group affiliation, direct contact with patients with COVID-19 and the respective medical ward also seem to play a role16. The workload in intensive care units in particular has been observed to directly increase mental health symptoms of the employees. This was particularly the case in England, where the number of ICU staff with mental health symptoms was high in younger nurses and fluctuated depending on the severity of the second wave17. In a study in Switzerland working in intensive care units was described with increased symptoms of anxiety and depression18.

Investigating factors causing distress during the pandemic, the role of information and media consumption needs special consideration. Even before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic social media consumption played a major role in mental well-being. A study showed that the emotions expressed by others on social media have an impact on the emotions of the user19. Current studies about the impact of social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic have also shown an elevated mental burden on people who increasingly obtain their information in social networks20,21 and even chronic stress and panic have been observed due to the so called “infodemic” that comprises the fact that misinformation have been spread as a kind of “digital epidemic”22. However, little is known about the potential role of social media exposure on psychological distress among healthcare professionals.

Objectives of the study

This study aims at understanding the mental health and its conditions of physicians, nurses, other medical staff and non-medical professionals in the health care system of 8 European countries during the third wave of COVID-19 with increased sanitary measures in Europe.

We aimed to focus on risk factors either specific to health-care professionals (e.g., working in ICU) or non-specific but overlooked so far in this specific population (e.g., exposure to social media).

A key focus was put on the professional groups of physicians and nurses with regard to the severity of symptoms in their respective ward, stressors, working hours, and sources of COVID-related information.

Methods

Study design and procedures

A cross-sectional survey was carried out by means of an online questionnaire that has been developed for the purpose of this and two former studies, that were carried out in 202023,24. The questionnaire was made available on SoSciSurvey25 and distributed within Europe in six languages (English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish). The link to the survey was distributed via email to personal and professional networks following a snowball sampling approach. Invitation emails were sent to colleagues at affiliations of all co-authors, i.e. clinical and research institutions in, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland. It was then further distributed to related institutions and to partner organizations, hospitals, and professional associations. Participants were also recruited via personal networks or public social networking groups, such as medical or nursing groups at Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook. The survey was launched on 25th November 2021 and closed on 28th February 2022.

The qualitative results of this survey that included answers in open text fields in this study period and those of the former study period were published elsewhere26.

We follow the reporting guidelines of the STROBE statements for observational studies27.

Ethical considerations

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Heidelberg University Medical Faculty (S-361/2020). Data collection was organized in compliance with the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The survey questionnaire was distributed in 8 European countries and all healthcare workers and associated staff at hospitals as well as non-medical staff were eligible to participate. Informed consent was obtained from the participants online prior to participation. No allowance was given for participating in the survey. All questionnaires were completed anonymously. Data security was granted by use of the SSL-encrypted platform SoSci Survey25.

Measures

The questionnaire has been described in detail in a former publication24. However, as some parts have been changed due to new requirements, the structure of the questionnaire will be repeated and the new sections described: in the first part, we asked for demographic data, exposure to people infected with COVID-19 in their daily life and at work, working hours per day, and the means by which people gain information about COVID-19 (multiple choice: Internet, social media, TV, communication with colleagues, other). Similar to the previous study24 we asked the mental health status using the short version of the Depression-Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21)24,28,29 and for stressors of nurses and physicians that has been derived from a previous study during SARS epidemic in 200329. The DASS questionnaire consists of 21 questions, seven each of which belong to the depression, anxiety, and stress subscale. Responses are given on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “did not apply to me at all” = 0, to “applied to me very much or most of the time” = 3.

Data analysis

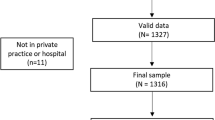

The data was analyzed with IBM SPSS statistics 2630. We collected data of 1439 participants and removed all datasets that were filled out outside the targeted countries (n = 41). The final analysis comprised data of 1398 participants. Missing values were omitted from the calculations without replacement.

We calculated descriptive statistics and reported frequencies, means, standard deviations, and percentages.

Following the manual of the DASS-2128, individual sum scores were calculated based on the depression, anxiety and stress subscales and multiplied by two. The depression subscale score was categorized as normal (0–9), mild (10–13), moderate (14–20), severe (21–27), and very severe depression (28+). The anxiety subscale score was categorized as normal (0–7), mild (8–9), moderate (10–14), severe (15–19), and extremely severe anxiety (20+). The total stress subscale score was categorized as normal (0–14), mild (15–18), moderate (19–25), severe (26–33), and extremely severe stress (34+)5. These subscales were then grouped as normal/mild; moderate; severe/very severe, following our previous approaches to ease the interpretation23,24, as mild symptoms of mental disorders show a high prevalence regardless of a pandemic like COVID-1931.

We created four groups: (1) physicians (including physicians and dentists), (2) nurses, (3) other health care professionals, which included “other job in healthcare system” and “volunteer in the context of medical pandemic aid”, and (4) non-medical staff consisting of professionals who usually do not work directly with the patients or their immediate environment.

A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was computed for each of the three DASS-21 scores as the dependent variable, with the two predictors being the profession group and contact with people infected by COVID at work, and working hours per week, own infection with COVID, country where the participant is actually living, age and gender as a covariate. We chose a robust test statistic of Pillai in case of violation of assumptions of normality and homogeneity of covariance matrices32.

We then focused on the groups of physicians and nurses only for whom we reported the three DASS-21 scores according to medical departments, as well as major stressors. A t-test was carried out for differences. Major ways of gaining information on COVID were calculated as frequencies and percentages. On the basis of this data, we carried out chi-square tests to find differences between the two groups. Finally, Eta-coefficients (η) were calculated to show associations between DASS-21 scores and the use of information sources.

In all analyses, p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

The sample size was 1398 people, of whom 237 were physicians, 459 were nurses, 351 comprised other healthcare professionals and 351 were non-medical professionals. The group of other health professionals consisted mainly of psychologists, educators, laboratory technicians, occupational therapists, dance and movement therapists, pharmacists, and medical-technical assistants. The group of non-medical professionals was very heterogeneous. This group consisted mainly of administrative employees, secretaries, researchers, educators, and computer scientists. The ages of the participants ranged from 19 to 78 (median: 42 years). A total of 369 (26.4%) males, 1024 (73.2%) females, and 5 non-binary people (0.4%) took part in the survey.

The distribution of people across countries is shown in Table 1. The distribution of the professional groups in the different countries are provided in the Supplementary File 1.

Vaccination status and working conditions during COVID-19 during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic

Results on the share of participants with infection, vaccination, contact to COVID at work, working hours and the respective medical unit are displayed in Table 2.

Opportunity to work from home (“home office”)

In Table 3 professional groups are presented who had the opportunity to work remotely.

Mental Health (DASS-21)

Across all professions and countries, a share of 23.3% (n = 326) report levels of depression that can be categorized as a severe/very severe degree. A share of 18.2% (n = 255) express severe/very severe levels of anxiety and 25.4% (n = 355) voice severe/very severe levels of stress. Nurses and non-medical staff show the highest degree of burden in all three symptom profiles. More details are presented in Table 4. Details of DASS-21 scores in the different countries are provided in the Supplementary File 2.

Comparison of the mental health of physicians, nurses, other healthcare professionals and non-medical professionals and the professionals having contact with COVID patients versus having no contact

A statistical analysis with a MANCOVA with the working hours per week, possibility to work from home (“home office”), own infection with COVID, country where the participant is actually living, age and gender showed a significant effect for profession (Pillai trace = 0.016, F3000 = 2479, P = 0.008) and also for the fact of being in contact with COVID-19 patients or not (Pillai trace = 0.007, F3000 = 3432, P = 0.016). The covariates showed also significant results (Working hours (Pillai trace = 0.030, F3000 = 14,163, P < 0.001); own infection with COVID-19 (Pillai trace = 0.009, F3000 = 4361, P = 0.005); country (Pillai trace = 0.013, F3000 = 5916, P < 0.001); age (Pillai trace = 0.017, F3000 = 7788, P < 0.001); gender (Pillai trace = 0.021, F3000 = 9843, P < 0.001).

In the between-subject analysis for profession in two of three DASS-scores showed significant results (DASS-D P < 0.023, DASS-A P < 0.001, DASS-S P = 0.308). Physicians showed in all three DASS-scores the lowest scores (Table 4). For the people having contact at work with COVID-patients all three DASS-scores showed a significant difference (DASS-D P = 0.001, DASS-A = 0.032, DASS-S P = 0.016).

Mental health in the medical units and workload of physicians and nurses

Depending on the workplace, the highest values on all three scales were found among staff in the intensive care units, ahead of staff in the general medical units and the emergency units (Table 5).

Job-related stressors of physicians and nurses

Among the medical staff, “uncertainty about when the epidemic will be under control” was rated highest, followed by “worry about inflicting COVID-19 on family”, “worry about lack of manpower”, “frequent modification of infection control procedures”, and “coworkers being emotionally unstable”. Participants were less concerned about to get blamed by their commanding officers. An overview of all stressors in the order of reported severity can be found in Table 6. Overall, all stressors were rated to a higher level by nurses than by physicians.

Information on COVID-19

In Table 7, we see the different sources of information. Both television and social media were less frequently reported by physicians as being a main source of information about COVID-19 (P < 0.001).

A further analysis revealed a weak positive association in the depression, stress, and anxiety scales with the use of social media as a main source of information about COVID-19 (DASS-D η = 0.05; DASS-A η = 0.11; DASS-S η = 0.88). More associations could be shown for television and internet, but only in the case of anxiety (DASS-A η = 0.05 and η = 0.06 respectively).

Discussion

Principal findings

One of our main findings in this European wide study is that nurses and other medical and non-medical health workers had higher scores in depression and anxiety scores as measured by the DASS-21 in comparison to physicians. The study was carried out to ask for symptoms and predictors of the mental health of physicians, nurses, and other professions in and outside of direct patient care during the third wave of the pandemic in winter 2021/2022. In the analysis, we considered frequently described risk factors such as age, gender, workload and country of residence of the participants. In total, the proportion of nurses with moderate and severe depression was higher than that of physicians. For anxiety, too, the proportion of nurses in the moderate and severe categories was higher. Similar findings were also reported in different studies and reviews12,15,33,34. In a Belgian sample, there was no direct influence of whether someone works directly with COVID patients, but rather an influence of the professional group on burnout and anxiety symptoms as well as on insomnia13. A study of Italian health professionals showed that nurses suffered more from overall psychological distress than physicians14. This difference was also demonstrated in a Belgian study35. An Italian study36 revealed a significantly higher risk for nurses and explained this, among other causes, by the fact that nurses were less involved in the decision-making processes and also spent significantly more time directly exposed to the infectious patients during their work.

Another main finding of our study was the correlation between the stress and depression scores and the working hours. This association can be supported by previous studies37. A Dutch investigation was able to show a connection between an increase in the prevalence of burnout, the occurrence of COVID-19, direct contact with COVID-19 patients, and the hours worked by professionals in ICUs38.

Physicians and nurses who worked directly with COVID-19 patients also had higher values in all DASS scores in our study. This correlation is also described in other studies10,39. A similar association was found in an Australian sample, for example, where caregivers with direct contact with COVID-19 patients had the most pronounced emotional exhaustion, while non-medical professionals with no contact had the lowest scores34. A meta-analysis showed higher values for anxiety and depression in the group of professionals with contact to COVID-19 patients40. In this meta-analysis, women, married individuals, individuals with children, and nurses had relatively high scores in both depression and anxiety. In summary, in addition to one's own exposure, fear for family members seems to play an important role through the fear of infecting them through one’s own exposure. Other fears referred to staff shortage as well as the often-increased contact with seriously ill patients or the concern about the deterioration of their condition. Compared to the previous first-wave study by Hummel et al.24 who used a comparable design, similar overall values were shown in the individual DASS scores, although it must of course be added that this is not a follow-up study.

The most frequently mentioned stressors were “Uncertainty about when the epidemic will be under control” and “Worry about inflicting COVID-19 on family”, which were the same as in the previous study24. Especially the worry about infecting the family which was also described before41. For the stressors, the nurses consistently showed higher mean values than did the physicians, which basically fits with the mental burden of the nurses described above. This might be explained by the longer duration they have to work directly with the patients. In addition to the other stressors, deficits in the acquisition of knowledge are weighted significantly higher by the nurses than by the practitioners. Other results of our survey that included as well coping strategies, have been published elsewhere26. There, the acquisition of knowledge was also a successful coping strategy. There still seems to be a stressor in the third wave of the pandemic, although this problem was already recognized at the beginning of the pandemic42. This result is also comparable to former findings that describe even a worsening of mental distress but in non-comparable time periods43,44,45.

Another important result of our study was the correlation of the use of social media with higher values in all DASS scales, although this connection could not be seen for other sources of information. A possible explanation might argue that increased social media use and the associated increased exposure to corresponding content were associated with increased anxiety20,21. Interestingly, this connection has already been revealed by an experimental study before the pandemic19, where the reduction of positive expressions led to fewer positive and more negative posts, and the reduction of negative posts led to opposite findings. On the other hand, loneliness, isolation, workload and fears might increase the use of social media as a means of compensation especially in the case of nurses who were burdened to a certain extent46. We found a weak positive correlation of social media use and DASS-scores. In line with the literature this should be interpreted as an indication why increased use of social media is associated with more stress and the associated increased values in the DASS scores in our study. Whether more stress leads to increased use of social media or a higher frequency of social media use evokes higher stress levels cannot be derived from our study. Future investigations are necessary to come to a causal conclusion regarding mental health and social media use in specific professional groups.

Limitations

Since the link to the online survey was distributed on the one hand through personal contacts and on the other hand via social networks, there was a very unequal distribution of the professional groups and of the gender of the participants in the different countries. In addition, non-occupational factors, such as the strictness of measures and the different dynamics of the pandemic in the individual countries over the survey period, certainly also played a role in mental health. We neither asked for details of institutional and governmental measures nor for the willingness of the participants to follow them. Overall, the participants cannot all be assigned to medical specialties or work areas, so that there could be an overrepresentation of employees in psychiatry. When asked about the sources of information, specific scientific journals were not asked about as a source of information for the participants. This can lead to a bias in the results, since a significant group of people and possibly a possible difference between the professional groups were not shown.

Conclusion

In summary, our study continued to provide numerous indications that the COVID-19 pandemic still is a significant stress factor for the healthcare system. When scores for stress were not statistically different, we found as a main result that nurses scored significantly higher on depression and anxiety than practitioners. These differences were also reflected in the different levels of stressors that we evaluated for nurses and physicians. In addition to the positive correlation of working hours with stress and depression and the positive connection between direct contact with COVID-19 patients and increased anxiety, depression, and stress, the highest psychological burden was shown in employees of intensive care units. As a secondary result we found a weak positive correlation between social media use and the DASS-scores. Further investigations are needed to clarify the role of social digital media as negative influencer on the mental health of healthcare professionals.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. 3 8 2022 (2022).

Rommel, A. et al. The COVID-19 disease burden in Germany in 2020. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0147 (2021).

Pires, S. M. et al. Disability adjusted life years associated with COVID-19 in Denmark in the first year of the pandemic. BMC Public Health 22, 1315. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13694-9 (2022).

Ge, Y. et al. Untangling the changing impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccination on European COVID-19 trajectories. Nat. Commun. 13, 3106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30897-1 (2022).

Wynter, K. et al. Hospital clinicians’ psychosocial well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal study. Occup. Med. 72, 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqac003 (2022).

Almalki, A. H. et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia: A year later into the pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 12, 797545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.797545 (2021).

Kunzler, A. M. et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Glob. Health 17, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00670-y (2021).

Phiri, P. et al. An evaluation of the mental health impact of SARS-CoV-2 on patients, general public and healthcare professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 34, 100806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100806 (2021).

Luceño-Moreno, L., Talavera-Velasco, B., García-Albuerne, Y. & Martín-García, J. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 5514. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155514 (2020).

Ferreira, S. et al. A wake-up call for burnout in Portuguese physicians during the COVID-19 outbreak: National survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 7, e24312. https://doi.org/10.2196/24312 (2021).

Mediavilla, R. et al. Sustained negative mental health outcomes among healthcare workers over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Public Health 67, 1604553. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604553 (2022).

Pappa, S. et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026 (2020).

Tiete, J. et al. Mental health outcomes in healthcare workers in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 care units: A cross-sectional survey in Belgium. Front. Psychol. 11, 612241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.612241 (2021).

Bonzini, M. et al. One Year Facing COVID. Systematic evaluation of risk factors associated with mental distress among hospital workers in Italy. Front. Psychiatry 13, 834753. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.834753 (2022).

de Kock, J. H. et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 21, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3 (2021).

Johnson, S. U., Ebrahimi, O. V. & Hoffart, A. PTSD symptoms among health workers and public service providers during the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 15, e0241032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241032 (2020).

Hall, C. E. et al. The mental health of staff working on intensive care units over the COVID-19 winter surge of 2020 in England: A cross sectional survey. Br. J. Anaesth. 128, 971–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2022.03.016 (2022).

Wozniak, H. et al. Mental health outcomes of ICU and non-ICU healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Intensive Care 11, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-021-00900-x (2021).

Kramer, A. D. I., Guillory, J. E. & Hancock, J. T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 8788–8790. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320040111 (2014).

Gao, J. et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 15, e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924 (2020).

Ni, M. Y. et al. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in Wuhan, China: Cross-sectional survey. JMIR Ment Health 7, e19009. https://doi.org/10.2196/19009 (2020).

Banerjee, D. & Meena, K. S. COVID-19 as an “Infodemic” in public health: Critical role of the social media. Front. Public Health 9, 610623. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.610623 (2021).

Du, J. et al. Mental health burden in different professions during the final stage of the COVID-19 lockdown in China: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 22, e24240. https://doi.org/10.2196/24240 (2020).

Hummel, S. et al. Mental health among medical professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in eight European countries: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 23, e24983. https://doi.org/10.2196/24983 (2021).

Leiner, D. J. SoSci Survey. In vol. 2022, Version 3.1.06 edn (2019).

Hummel, S. et al. Unmet psychosocial needs of health care professionals in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mixed methods approach. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 9, e45664. https://doi.org/10.2196/45664 (2023).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 147, 573. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 (2007).

Lovibond, S. H. & Lovibond, P. F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Psychology Foundation of Australia, 1996).

Lee, S.-H. et al. Facing SARS: Psychological impacts on SARS team nurses and psychiatric services in a Taiwan General Hospital. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 27, 352–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.04.007 (2005).

IMB Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. In 26.0 edn (IBM Corp, 2019).

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3 (2019).

Olson, C. L. Comparative robustness of six tests in multivariate analysis of variance. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 69, 894–908. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1974.10480224 (1974).

Hao, Q. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 12, 567381. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.567381 (2021).

Maunder, R. G. et al. Trends in burnout and psychological distress in hospital staff over 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic: A prospective longitudinal survey. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 17, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-022-00352-4 (2022).

Franck, E. et al. Role of resilience in healthcare workers’ distress and somatization during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study across Flanders, Belgium. Nurs Open 9, 1181–1189. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1159 (2022).

Lasalvia, A. et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 30, e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020001158 (2021).

Fiabane, E. et al. Psychological and work-related factors associated with emotional exhaustion among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italian hospitals. Nurs. Health Sci. 23, 670–675. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12871 (2021).

Kok, N. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 immediately increases burnout symptoms in ICU professionals: A longitudinal cohort study. Crit. Care Med. 49, 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004865 (2021).

Hu, N. et al. The pooled prevalence of the mental problems of Chinese medical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 303, 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.045 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety and depression among frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 10, 984630. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.984630 (2022).

Walton, M., Murray, E. & Christian, M. D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 9, 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872620922795 (2020).

Frenkel, M. O. et al. Stressors faced by healthcare professionals and coping strategies during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. PLoS ONE 17, e0261502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261502 (2022).

Probst-Hensch, N., Jeong, A., Keidel, D., Imboden, M. & Lovison, G. Depression trajectories during the COVID-19 pandemic in the high-quality health care setting of Switzerland: The COVCO-Basel cohort. Public Health 217, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.01.010 (2023).

Holton, S. et al. Psychological wellbeing of Australian community health service staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 405. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09382-y (2023).

Th’ng, F. et al. Longitudinal study comparing mental health outcomes in frontline emergency department healthcare workers through the different waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 16878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192416878 (2022).

Häussl, A. et al. Psychological, physical, and social effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 68, 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12716 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants for sharing their experiences and taking part in our study. For the publication fee we acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the funding programme “Open Access Publikationskosten” as well as by Heidelberg University.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.D. and G.M. contributed equally, they analysed the data and wrote the main manuscript text, S.H. reviewed the statistics, S.M., C.B., R.A., R.L.D., O.R., V.F., I.T., S.F. and C.L. collected data, C.H., S.W. and J.H.S. conceptualized the study and supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dechent, F., Mayer, G., Hummel, S. et al. COVID-19 and mental distress among health professionals in eight European countries during the third wave: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep 14, 21333 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72396-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72396-x

- Springer Nature Limited