Abstract

Study design

Qualitative studies.

Objective

To develop clear and specific administration and scoring procedures for the Spinal Cord Independence Measure Version 3.0 as a performance-based and interview assessment.

Setting

Research lab.

Methods

Modified Delphi Technique survey methods were used in this study. Previously developed SCIM-III administration and scoring procedures for performance-based and interview versions were presented to clinicians experienced in SCI and SCIM-III using the Qualtrix (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) online survey platform. Summary and descriptive statistics were used to assess the percent agreement survey responses.

Results

Three survey rounds were necessary to achieve 80% agreement or above for the performance-based version. Two survey rounds were necessary to achieve 80% agreement or above on the interview version.

Conclusions

This study describes the development of standardized administration and scoring procedures for the self-care and mobility sub-scales of the SCIM-III as a performance-based and interview version.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM-III) evaluates the level of independence and ability of individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) to perform routine daily tasks [1, 2]. It is comprised of 19 items in three domains: self-care (6 items), respiration and sphincter management (4 items), and mobility (9 items) [3]. Each domain is scored on an ordinal scale based on the clinical relevance and importance for individuals with SCI [3, 4]. Scoring accounts for the amount of assistance provided by another person and use of adaptive equipment by assigning higher scores for less assistance or aids [5].

Since its introduction in 1997, the SCIM-III has been frequently used in SCI clinical trials. Three large-scale adult studies [6,7,8] evaluated the validity and reliability of the SCIM-III as a functional recovery instrument and established moderate-to-strong reliability and validity. Additional work examined clinically important differences in SCIM-III scores [9], established target values for SCIM-III for neurological levels in complete SCI [10], and developed and validated a self-report version [11]. Most recently, scores from the ISNCSCI motor examination [12] and SCIM-III scores from select items have been used to develop the Spinal Cord Ability Ruler (SCAR) to enable longitudinal assessment of volitional performance on a linear metric from the time of injury [12].

Despite its widespread use, standardized guidelines for administering and scoring the SCIM-III were never developed, which has led to variability in interpretation of scores [13] and feedback that administration and scoring descriptions are incomplete and unclear [14]. Variability in administering and scoring standardized clinical outcome assessments, such as the SCIM-III [14], has implications for clinical practice and clinical trials. Reimbursement, length of stay, and potential for over-estimating or under-estimating function are at risk. For clinical trials, variability in administration and scoring poses a threat to reliability within a single trial and limits the opportunity for comparison of outcomes and pooling of data across several trials. Lack of standardization can also impact test results and measurement properties [14]. For performance-based measures, such as the SCIM-III, reliance on human raters to translate human motor performance into a metric underscores the importance for clear administration and scoring procedures.

Performance-based assessments involve having the participant perform certain movements or tasks, which allow for a direct assessment of the participant’s abilities. Although performance-based assessments may be more objective and potentially less biased than self-report and interview-based assessments, they are time-consuming and may not be feasible within all practice environments and clinical trial settings due to limited time and resources, such as equipment and appropriate environments for observation [15, 16], and transportation challenges associated with returning to the clinical setting. Reliability of SCIM-III scores when obtained through self-report and interview are acceptable, and these modes of administration require less time (10–15 min for interview compared to 30–45 min by observation), allow for rapid data collection, and can be utilized across multiple settings [16, 17]. Similarly, administration of the SCIM-III by interview may mitigate the amount of missing data in longitudinal studies.

When administrating the SCIM-III as a performance-based measure and as an interview, it is important to have guidelines that standardize administration and scoring of each item. Standardized guidelines would provide a safeguard for variability in item set-up, execution, scoring (performance-based administration), and in the structure and content of questions for each item (interview administration). Previous studies have recognized the need for better training in and standardization of administration and scoring of the SCIM-III [8, 15].

In response to the need for standardization in administration and scoring of the SCIM-III, and in recognition of the serious limitations in SCI clinical outcome measures, we engaged experts in SCI practice and research to create standardized procedures for the SCIM-III when administered and scored as a performance-based measure and standardized procedures for the SCIM-III when administered and scored by interview.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to develop standardized administration and scoring procedures for the SCIM-III items when administered as a performance-based assessment and by interview. We sought to develop clearly written administration procedures that aligned with the intent of SCIM-III items and that were feasible to implement in practice environments and clinical trial settings. We also sought to develop procedures to aid in accurate scoring of SCIM-III items when administered as a performance-based measure and interview.

Methods

The Modified Delphi Technique is an iterative process that uses a systematic progression of repeated rounds of surveys to allow for feedback and revisions as a way to build consensus among experts in areas and for purposes where knowledge is complex, incomplete, or poorly understood [18, 19]. The defining feature of the Modified Delphi is that the collated responses from previous questionnaires are integrated into each new questionnaire, and the experts being questioned are able to reconsider their previous judgments, revising and responding as appropriate [20]. In health care, the Modified Delphi Method has been used for a variety of purposes including the development of clinical practice guidelines. In this study, we used the Modified Delphi to engage SCI clinicians and researchers for the purposes of developing standardized administration and scoring procedures for the SCIM-III.

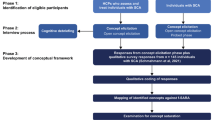

As shown in Fig. 1, a multi-stage iterative process [19, 21, 22] (Fig. 1) was used to create initial administration and scoring procedures for each SCIM-III item and to garner feedback on clarity of wording related to administration, scoring guidelines, and feasibility of administering SCIM-III performance-based items as specified. This iterative process was used until consensus was reached at 80% agreement among experts that the administration and scoring were clearly written, that the procedures aided in administration and scoring, and it was feasible to execute. Two independent Modified Delphi processes were implemented. The first Modified Delphi focused on developing guidelines for the SCIM-III for administration and scoring as a performance-based measure (March 2020–May 2020), and the second Modified Delphi process was undertaken to develop guidelines for the SCIM-III for administration by interview (February 2021–March 2021). The two-staged approach was used to mitigate confusion about mode of administration.

As shown in Fig. 1, an initial set of administration and scoring guidelines were established based on the SCIM-III literature and SCIM-III experience and were used as the basis for the first survey.

Survey Development

As a starting point, initial administration and scoring procedures for each SCIM-III mobility and self-care item were developed for performance-based standardization. These procedures were slightly revised for SCIM-III mobility and self-care items for interview, and initial procedures for respiration and sphincter were created (we did not include respiration or sphincter in the performance-based guidelines) (Fig. 1).

Specifically, for each SCIM-III mobility and self-care item, an explicit administration and scoring procedure was provided followed by four “yes/no” questions: 1. Are the (administration) instructions clear? 2. Could you replicate this in your clinic? 3. Are the scoring instructions clear? 4. Would you be able to determine a SCIM-III score? This resulted in a total of 60 questions for the first survey for the Modified Delphi Process for performance-based standardization (15 SCIM-III mobility\self-care items X 4 “yes/no questions per item). Only two “yes/no” questions were asked for each SCIM-III item for interview standardization: 1. Are the interview prompts clear? 2. Could you replicate this in your clinic? Thus, for the first survey for the Modified Delphi process for interview standardization, there were 38 questions (19 SCIM-III items X 2 “yes/no” questions per item). Survey respondents were asked to answer each yes/no question, provide a rationale for a response of “no”, and suggest alternatives to the content or wording to improve clarity, consistency, and standardization.

Consistent with Modified Delphi Methodology, subsequent surveys contained revised procedure guidelines based on expert input and the same “yes/no” questions. Surveys were completed anonymously and remained open for 2 weeks for each iterative round, with an e-mail reminder after one week to boost response rate. A statement of consent was provided in the email invitation.

Survey respondents

Purposeful [23] and snowball [24] sampling were used to recruit survey participants. Purposeful sampling was done by e-mailing an invitation to content experts known to the principal investigator with a description of the study purpose and a link to the survey. Content experts were asked to forward the e-mail invitation to their colleagues who work with the SCI population (snowball sampling).

Data analysis

Summary and descriptive statistics were used to assess percent agreement of survey responses. For yes-no questions that had at least 80% response rate of “yes”, procedures were considered clearly written and feasible to implement in usual practice and clinical trial environments. For yes-no questions that did not reach 80% response rate of “yes”, procedures were revised based on respondents’ feedback and exposed to subsequent survey rounds until 80% agreement was achieved. Once 80% agreement was obtained for each question for each SCIM-III item, administration and scoring guidelines for performance-based administration and for administration by interview were formatted and prepared for widespread dissemination.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the majority of respondents were physical and occupational therapists, had over 10 years of SCI experience, and used the SCIM-III, primarily in rehabilitation and research settings. The majority of respondents reported administering the SCIM-III using a combination of observing performance and interview.

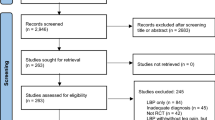

Three iterative rounds of the performance-based survey were required to reach 80% agreement for each of the four questions for each SCIM-III self-care and mobility items (Table 2). Two iterative rounds of the interview survey were required to reach 80% agreement for all items (Table 3).

Modified Delphi process for standardization of procedures for administration and scoring by performance-based measure

Table 2 shows the response rate of “Yes” to each of the four questions asked for the mobility and self-care items in the Modified Delphi process for standardization for the performance-based measure. As shown in the first survey, the response of “yes” for the administration procedures for 6 items and for the scoring procedures for 8 items was obtained in at least 80% of respondents. For the remaining questions (n = 36) that did not reach 80% response of “yes”, feedback from respondents (Table 4) was used to revise the administration and scoring procedures, and these items were exposed to expert opinion and feedback in survey. As shown in Table 2, with the exception of the two questions asked for scoring procedures for one item (Mobility in Bed and Action to Prevent Pressure Injuries), survey 2 obtained at least an 80% response rate of “yes” for every question for each item. Respondent feedback was used to revise the scoring procedures for the Mobility in Bed and Action to Prevent Pressure Injuries (Table 4), and the item was again exposed to expert opinion and feedback in a third survey.

Modified Delphi process for standardization of procedures for administration and scoring by interview

Table 3 shows the response rate of “Yes” for each of the two questions asked for each of the SCIM IIII items in the Modified Delphi process for standardization for interview. As shown in the first survey, the response rate of “yes” for the questions, “are the interview prompts clear?” and “could you replicate this in your clinic?”, were at least 80% for 13 items and for 16 items, respectively. For the items that did not reach 80% response rate for either question, feedback from survey 1 (Table 4) was used to revise the administration and scoring procedures, which were exposed to expert review in the second survey. Of note, although the 80% threshold was reached for two items (use of toilet; transfer from wheelchair to toilet/tub), administration and scoring were revised based on survey 1 feedback (Table 4) and included in the second survey. As shown in Table 3, an 80% or greater response rate of yes was obtained for each SCIM-III item.

Discussion

In this study, a Modified Delphi Technique was used to iteratively obtain feedback and establish consensus among experts on the standardization of administration and scoring procedures for the SCIM-III when administered as a performance-based measure and as an interview. Owing to the widespread use of the SCIM-III in practice and research and the concerns about the lack of available standardized procedures for administration and scoring, we established procedural guidelines that are clear, mitigate variability, accessible, and that are feasible to implement in practice and research settings.

The inherent lack of guidance of the existing SCIM-III leaves it open to interpretation and variability. Given the potential variability in performance-based outcome measures, it is important to establish fidelity in administration and scoring to assess whether or not an individual implements an evaluation as intended [25, 26]. In a clinical trial setting, when administering outcome measures with different administration and scoring procedures, fidelity is essential to prevent “rater drift and contamination” [27]. This is significant considering the reliability and validity of a measure are “dependent on the consistency with which it can be administered, scored, and interpreted” [28]. Moreover, because users of clinical outcome measures frequently do not read clinical outcome measures users’ manuals [29], we created scoring flow diagrams that are intuitive and allow for low burden and accurate scoring.

While we did not collect information on geographical location of the respondents, purposeful sampling included distribution of the email invitation to international experts. One possible limitation for not reaching the 80% threshold in the first surveys is due to regional variations in English lexicon. Certain terms such as “electric aide”, “durable medical equipment” and “tick” seemed to be relevant for some regions and not for others. Medical jargon and use of abbreviations also likely contributed to responses of “no” for some items. Specifically, the definitions for durable medical equipment, adaptive devices, specific setting, total partial assistance, and partial assistance were created, as respondents identified these terms as being too complex or “technical” for use in SCIM-III interview. As such, the procedure manuals include an abbreviation list and glossary of terms with definitions to decrease areas of potential confusion and to make the measure easier to use for those with limited experience with SCIM-III. Gender-specific pronouns were removed to be more inclusive of all gender identities.

Survey responses and feedback led to revision of administration and scoring procedures for the SCIM-III items, resulting in standardized and clearly written administration and scoring procedures for the SCIM-III. The methodology did not alter any established SCIM-III item or scoring criteria [1, 3, 5, 6]. Our intent was to maintain the SCIM-III as it was developed and make no changes to items or scoring. Several respondents reported concerns with the inconsistent scoring scale; meaning sometimes scoring is 0-2 while for other items it is 0-8. It was important to state that the scoring is directly from the original SCIM-III, and our team did not feel it within the scope of our work to revise the scoring structure. Our work focused entirely on providing clear and specific instructions for administering and scoring SCIM-III items via performance-based measure and individual interview, with the goal to provide the field with a resource to assess endpoints of usual care and clinical trials.

Performance-based version

An introduction and general instructions for the survey and SCIM-III performance-based procedures were necessary to provide background information and decrease administrator burden when completing the survey and administering this version of the SCIM-III. Respondents of the performance-based survey were instructed to review both the written instructions and scoring flowsheets prior to answering survey questions since these were developed to be used in conjunction with each other for each SCIM-III item. In both versions, the starting prompt of each flowsheet was moved towards the top-left corner and the final scores, which were made rectangular and blue to differentiate from the rest of the flowsheet, were organized in numerical order and placed on either the right or bottom of the flowsheet.

Administration and scoring procedures were not developed for the respiration and sphincter management subscale of the SCIM-III. This portion was excluded in the performance-based procedures because of the inability to adequately demonstrate and assess respiratory elements with a performance measure. Additionally, having participants demonstrate their bowel and bladder program would be an undue burden. In contrast, the self-care and mobility portions were included because clinical trials are more focused on mobility and upper extremity function, which are more directly related to those sections. Moreover, in the rehabilitation setting, it is frequently the occupational and physical therapists who use the SCIM-III; therefore, if transformed into a performance measure, the self-care and mobility portions would be assessed by an occupational or physical therapist.

Initial administration procedures gave examples of items that could be used or tasks to perform. However, survey respondents reported that the initial examples were not specific enough and the expectation was still unclear. For example, the administration procedures for the dressing item included “raise arms”. In round 2, it was revised to “touch the back of your head”. This created clear expectations for both the participant and administrator. We further needed to develop a list of recommended materials to be used for each item, adding to the standardization of our manual. This list included items such as an 8 oz sandwich container, 12 oz plastic cup, and a reusable metal knife and fork.

When standardizing administration procedures for dressing and bathing items, only a few specific tasks were selected to reduce time and participant and administrator burden. For example, for bathing, two body parts were selected to mimic upper body (non-dominant arm and low back) and lower body bathing (perineal area and dominant lower leg). The parts of the task that were selected were ones that incorporated most of the task or the more challenging aspects of the task. It was necessary to limit the task in this manner for the sake of time and clinical usability.

Lastly, modifications were made to all scoring procedures to increase flow and clarity. Although many of the scoring procedures obtained above 80% agreement in round 1, it was determined that it would be beneficial to apply the changes made to those with below 80% agreement to all flowsheets. The flowsheets were simplified and made as consistent as possible to ease administrator burden. They were then re-submitted in round 2 for review. After round 2, only 1 item required further revisions. This item was revised per the respondent’s comments and submitted into a third and final round.

Interview version

An introduction was provided at the start of the round 2 survey to address some of the feedback provided in round 1. Participants provided comments that aligned with many of the limitations of the original SCIM-III such as the vagueness of core tasks, use of medical jargon and abbreviations, and the overall lack of accessibility of the measure to the patient population.

The original SCIM-III is not inclusive of all scenarios that individuals with SCI may participate in. To clarify the intent to retain fidelity to the original SCIM-III in terms of content, a general statement was made that: “Not every case/scenario may be captured in these flowsheets… Despite being an appropriate consideration for persons with SCI, some conditions and situations were not represented in the interview flowsheets in order to adhere to the original SCIM-III guidelines.” One respondent emphasized that a person could perform a pressure relief in a wheelchair in more ways than just “doing push-ups in wheelchair,” which is the only consideration in the original SCIM-III scoring criteria. These comments were reasoned to be issues and limitations with the original SCIM-III form and not necessarily with the interview flowsheets.

In developing the interview version, participants in round 1 provided feedback that the flowsheets were not intuitively organized and therefore the decision was made to alter the formatting and change the colors and shapes shown on the flowsheets. The shape of the initial prompt was changed to a circle and moved to the top of each flowsheet, making it apparent for administrators where to begin the sequence of prompts. The shape change also set the initial prompt apart from the subsequent diamond-shaped prompts. A sample flowsheet with these changes was provided in the beginning of the round 2 survey with instructions on how to navigate the flowsheets.

Instead of focusing on the positioning of the individual during the bathing and dressing items, the prompts in the flowsheets were altered to be more consistent with the scoring guidelines which emphasize level of assistance provided, use of adaptive devices, and/or the use of specific settings to facilitate completion. In many cases, small modifications to prompts resulted in less prompts on the flowsheets overall, reducing the complexity of scoring and increasing ease of use of the interview format compared to the original SCIM-III. As indicated by 80% agreement on all the SCIM-III flowsheets in the round 2 survey, structural changes allowed for a conciseness of language in subsequent prompts and a clearer path through the flowsheets, decreasing the burden of administration and scoring. Standardizing the interview prompts while retaining fidelity to the original SCIM-III form makes the SCIM-III more accessible not only to those administering the assessment, but also to the individuals.

Limitations

A limitation in this study is our sampling methods. By utilizing purposeful and snowball sampling with health professionals and researchers known by the principal investigator, we may have limited the experience, practice settings, and familiarity with up-to-date practice recommendations of the participant pool. Moreover, the content experts selected are heavily involved in the SCI community, actively participate in SCI associations and their annual meetings, and engage in research and other educational opportunities. It is important to note that there are many health professionals and researchers who work with SCI populations but may not be included because they are not known to our PI. Moreover, because responses were not forced, not all survey participants responded to every question.

Dropout was evident in the interview survey between round 1 and round 2 where the response rate decreased by 15 total participants. Round 2 of the interview survey had fewer questions (N = 26) (9 SCIM-III items X 2 “yes/no” questions per item; 5 demographic questions; 3 SCIM-III-related questions) than round 1 (N = 38). There are a few factors that may have caused dropout. One possible reason is over-sampling. Despite the year gap between surveys, by using the same participant pool, individuals may have felt burdened by completing multiple surveys. Another reason may have been technical issues with accessing the survey link.

Future directions

In the performance-based survey, the questions regarding respondents’ level of experience with the SCIM-III revealed that while majority had experience with the SCIM-III (65–75%), about 6.5–14.7% used the SCIM-III as a performance measure alone. Most respondents reported using the SCIM-III as a combination of both the performance and interview/self-report (56–67%). In the interview survey, 58.3–75.0% of participants were familiar with the SCIM-III. Of those individuals, 11.1–25.0% reported they use the SCIM-III as interview in their practice and 22.2–41.7% used the SCIM-III as performance measure alone. Approximately 33.3–66.7% reported to using the SCIM-III as a combination of a performance measure and interview/self-report. Based on these findings, it may be beneficial to compare the two distinct measures developed here to the original SCIM-III for accuracy and reliability.

Conclusion

Standardized administration and scoring procedures for both the performance-based and interview formats of the SCIM-III have been developed, and consensus on their clarity and feasibility established, and may be a useful resource for clinical trial programs and practice environments. They are available for download at no cost from the Jefferson College of Rehabilitation Sciences Center for Outcomes and Measurement website (https://www.jefferson.edu/university/rehabilitation-sciences/departments/outcomes-measurement/measures-assessments/spinal-cord-independence-measure-version-iii-administration-and-scoring-guidelines.html).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files]. As stated in our conclusions, the completed guidelines resulting from this study are available on the Center for Outcomes and Measurement website, https://www.jefferson.edu/academics/colleges-schools-institutes/rehabilitation-sciences/departments/outcomes-measurement/measures-assessments/spinal-corde-independence-measure-v3.html.

References

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Steinberg F, Philo O, Ring H, Ronen J, et al. The Catz-Itzkovich SCIM: a revised version of the spinal cord independence measure. Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23:263–8.

De Almeida C, Coelho JN, Riberto M. Applicability, validation and reproducibility of the spinal cord independence measure version III (SCIM III) in patients with non-traumatic spinal cord lesions. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:2229–34.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A. SCIM-spinal cord independence measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:850–6.

Ackerman P, Morrison SA, McDowell S, Vazquez L. Using the spinal cord independence measure III to measure functional recovery in a post-acute spinal cord injury program. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:380–7.

Catz A, Itzkovich M, Tesio L, Biering-Sorenson F, Weeks C, Laramee MT, et al. A multi-center international study on the spinal cord independence measure, version III: Rasch psychometric validation. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:275–91.

Itzkovich M, Gelernter I, Biering-Sorenson F, Weeks C, Laramee MT, Craven BC, et al. The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) version III: reliability and validity in a multi-center international study. DisabilRehabil. 2007;29:1926–33.

Bluvshtein V, Front L, Itzkovich M, Aidinoff E, Gelernter I, Hart J, et al. SCIM III is reliable and valid in a separate analysis for traumatic spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:292–6.

Anderson KD, Acuff ME, Arp BG, Backus D, Chun S, Fisher K, et al. United States (US) multi-center study to assess the validity and reliability of the spinal cord independence measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord. 2011;49:88–885.

Scivolette G, Tamburella F, Laurenza L, Molinari M. The spinal cord independence measure: how much change is clinically significant for spinal cord injury subjects. DisabilRehabil. 2013;35:1808–13.

Aidinoff E, Front L, Itzkovich M, Bluvshtein V, Gelernter I, Hart J, et al. Expected spinal cord independence measure, third version, scores for various neurological levels after complete spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:893–6.

Fekete C, Eriks-Hoogland I, Baumberger M, Catz A, Itzkovich M, Luthi H, et al. Development and validation of a self-report version of the spinal independence measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord. 2013;51:40–47.

Reed R, Mehra M, Kirshblum S, Maier D, Lammertse D, Blight A, et al. Spinal cord ability ruler: an interval scale to measure volitional performance after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:730–38.

Anderson K, Aito S, Atkins M, Biering-Sorenson F, Charlifue S, Curt A, et al. Functional recovery measures for spinal cord injury: an evidence based review for clinical practice and research. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:133–44.

Macdermid JC, Law M, Michlovitz SL. Outcome measurement in evidence based rehabilitation. In: Law M, Macdermid J, editors. Evidence based rehabilitation: a guide to practice (3rd edition). Slack Incorporated; 2014. p. 65–104.

Saberi H, Vosoughi F, Derakhshanrad N, Yekaninejad M, Khan ZH, Kohan AH, et al. Development of Persian version of the spinal cord independence measure III assessed by interview: a psychometric study. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:980–6.

Itzkovich M, Shefler H, Front L, Gur-Pollack R, Elkayam K, Bluvshtein V, et al. SCIM III (Spinal Cord Independence Measure version III): reliability of assessment by interview and comparison with assessment by observation. Spinal Cord. 2017;56:46–51.

Itzkovich M, Tamir A, Philo O, Steinberg F, Ronen J, Spasser R, et al. Reliability of the Catz-Itzkovich spinal cord independence measure assessment by interview and comparison with observation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82:267–72.

Hasson F, Keeney S, Mckenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–15.

Meshkat B, Cowman S, Gethin G, Ryan K, Wiley M, Brick A, et al. Using an e-Delphi technique in achieving consensus across disciplines for developing best practice in a day surgery in Ireland. J Hosp Adm. 2014;3:1–8.

Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi technique in health sciences: a map. Front Public Health. 2020; https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:1–88.

Green B, Jones M, Hughes D, Willimas A. Applying the Delphi technique in a study of GP’s information requirements. Health Soc Care Community. 1999;7:198–205.

Emmel, N. Purposeful sampling. In: Sampling and choosing cases in qualitative research: a realist approach. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2013. p. 33–44.

Morgan, D. Snowball sampling. In: Given L, editor. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc.; 2008. p. 816–7.

Mowbray CT, Holter MC, Teague GB, Bybee D. Fidelity criteria: development, measurement, and validation. Am J Eval. 2003;24:315–40.

Walton H, Spector A, Williamson M, Tombar I, Michie S. Developing quality fidelity and engagement measures for complex health interventions. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25:39–60.

Spell LA, Richardson JD, Basilakos A, Stark BC, Teklehaimanot A, Hillis AE, et al. Developing, implementing, and improving assessment and treatment fidelity in clinical aphasia research. Am J Speech-Lang Pathol. 2020;29:286–98.

Reed DK, Sturges KM. An examination of assessment fidelity in the administration and interpretation of reading tests. Remedial Spec Educ. 2012;34:259–68.

Novick DG, Ward K. Why don’t people read the manual. Departmental Papers. 2006;15.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Isa A. McClure, MAPT, Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation and Rebecca Martin, OTD, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for their contributions in the development of the standardized administration and scoring procedures. We further acknowledge our study respondents who participated in the surveys unnamed. Their expertise greatly informed the development of the SCIM-III standardized administration and scoring procedures.

Funding

This study was funded by departmental funds from the Department of Occupational Therapist in the Jefferson College of Rehabilitation Sciences in Thomas Jefferson University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RYK was responsible for leading data collection and analysis of Delphi for SCIM performance-based assessment, developing Delphi surveys for interview assessment, and leading the writing of the manuscript. CCT contributed by assisting in developing Delphi surveys for performance-based and interview assessment, collecting and analyzing data, and writing the manuscript. GH led the data collection and analysis of Delphi for SCIM interview assessment and assisted with writing the interview assessment portions of the manuscript. MJM was responsible for the conceptual design of the study, leading the development of the Delphi surveys, assisting in data analysis, and an equal in writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB), “Spinal Cord Independence Measure, Version III (SCIM-III) Procedure Development: A Modified Delphi Survey” (Departmental) Control #20E.150. We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers/animals were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, R.Y., Thielen, C.C., Heydeman, G. et al. Standardized administration and scoring guidelines for the Spinal Cord Independence Measure Version 3.0 (SCIM-III). Spinal Cord 61, 296–306 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-023-00891-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-023-00891-5

- Springer Nature Limited