Abstract

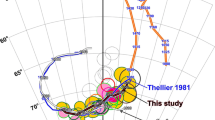

THE traditional view that Christopher Columbus discovered magnetic declination on his first voyage to the West Indies in 1492 was put forward with great force by Bertelli1 towards the end of the last century and has been repeated by many since. On the other hand, Crichton Mitchell2, after having examined the evidence on which this claim was based, concluded that not only did Columbus not discover magnetic declination but that the existence of declination was known in Europe as early as 1450. In the past few decades, however, .the Columbus controversy has become irrelevant with the researches of Wang Chen-To3 and Needham4, who have shown that the credit for the discovery of declination must go to the Chinese. Needham, in particular, has tabulated eighteen recorded Chinese compass observations of declination covering the period about 720–1829. These are of interest not only to historians but also to geophysicists, for they represent the earliest recorded direct observations of the Earth's magnetic field. The question of their validity is therefore of great importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bertelli, T., Proc. Intern. Meteorol. Congr., Chicago (1893).

Crichton Mitchell, A., Terr. Magnet Atmos. Elec., 42, 241 (1937).

Wang Chen-To, Chin. J. Arch., 4, 185 (1950).

Needham, J., Science and Civilization in China, 4, Pt. 1, 301 (Cambridge University Press, London, 1962).

Wylie, A., North China Herald (March 15, 1859); reprinted in Chinese Researches, Sci. Sect. 156 (Shanghai 1897, Peiping 1936).

Vestine, E. H., LaPorte, L., Cooper, C., Lange, I., and Hendrix, W. C., Carnegie Inst. Washington, Publ. 578 (1947).

Jenny, W. P., Terr. Magnet Atmos. Elec., 38, 97 (1933).

Watanabe, N., Nature, 182, 383 (1958); Kagaku, 28, 24 (1958); J. Fac. Sci., Univ. Tokyo (Sect. V), 2, 1 (1959).

Bullard, E. C., Freedman, C., Gellman, H., and Nixon, J., Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc., A, 243, 67 (1950).

Yukutake, T., Bull. Earthquake Res. Inst., 40, 1 (1962).

Orlov, V. P., in Physics of the Solid Earth (Akad. Nauk SSSR Izv) (edit. by Burlatskaya, S. P., Nechaeva, T. B., and Petrova, G. N.), 6, 383 (1965).

Burlatskaya, S. P., Nechaeva, T. B., and Petrova, G. N., Physics of the Solid Earth (Akad. Nauk SSSR Izv), 6, 380 (1965).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

SMITH, P., NEEDHAM, J. Magnetic Declination in Mediaeval China. Nature 214, 1213–1214 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1038/2141213b0

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/2141213b0

- Springer Nature Limited