Abstract

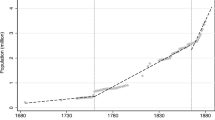

During the first three decades of the People's Republic of China, income differences across social classes were compressed. Formal education was not an important determinant of personal income. In this study, there was no difference in income between white-collar and blue-collar families, although white-collar parents had more education than blue-collar parents. In urban China, where population density was high, couples of different occupational status appeared to make different trade-offs between quantity and quality of children. Urban white-collar couples had fewer, but better-educated, children than their blue-collar counterparts. In rural areas, white-collar couples still had better educated children than blue-collar couples, but no difference was found in lifetime reproductive success. High population density and an occupational structure that incidentally helped reinforce unequal distribution of cultural capital in the population encouraged urban couples with different levels of resources (i.e., cultural capital rather than income in this case) to adopt different reproductive strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Anderson, K. G., Kaplan, H., & Lancaster, J. B. (1999). Parental care by genetic fathers and stepfathers I: Reports from Albuquerque man. Evolution and Human Behavior 20, 405–431.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). Interaction between quantity and quality of children. In T. W. Schultz (Ed.), Economics of the Family: Marriage, Children, and Human Capital (pp. 81–90). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bian, Y. (1996). Chinese occupational prestige: A comparative analysis. International Sociology 11, 161–186.

Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2000). Optimizing offspring: The quantity-quality tradeoff in agropastoral Kipsigis. Evolution and Human Behavior 21, 391–410.

Charnov, E. L. (1982). The Theory of Sex Allocation. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Clutton-Brock, T., & Godfray, C. (1991). Parental investment. In J. R. Krebs, & N. B. Davis (Eds.), Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach (pp. 32-68). London: Blackwell.

Dankert, G., & van Ginneken, J. (1991). Birth weight and other determinants of infant and child mortality in three provinces of China. Journal of Biosocial Science 23, 477–489.

Deng, Z., & Treiman, D. J. (1997). The impact of the Cultural Revolution on the trends in educational attainment in the People's Republic of China. American Journal of Sociology 103, 391–428.

Goody, J. (1983). The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Hannum, E., Xie, Y. (1994). Trends in educational gender inequality in China: 1949-1985. Social Stratification and Mobility 13, 73–98.

Kaplan, H. (1994). Evolutionary and wealth flows theories of fertility: Empirical tests and new models. Population and Development Review 20, 753–791.

Kaplan, H. (1996).A theory of fertility and parental investment in traditional and modern human societies. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 39, 91–135.

Kaplan, H., & Lancaster, J. B. (2000). The evolutionary economics and psychology of the demographic transition to low fertility. In L. Cronk, N. Chagnon, & W. Irons (Eds.), Adaptation and Human Behavior: An Anthropological Perspective (pp. 283–322). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Lam, D. (2003). Evolutionary biology and rational choice in models of fertility. In K. W. Wachter, & R. A. Bulatao (Eds.), Offspring: Human Fertility Behavior in Biodemographic Perspective(pp. 322-338). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Lancaster, J. B. (1997). The evolutionary history of human parental investment in relation to population growth and social stratification. In P. A. Gowaty (Ed.), Feminism and Evolutionary Biology (pp. 466-488). New York: Chapman Hall.

Lavely, W., Xiao, Z., Li, B., & Freedman, R. (1990). The rise in female education in China: National and regional patterns. China Quarterly 121, 61–93.

Lessells, C. M. (1991). The evolution of life history. In J. R. Krebs & N. B. Davis (Eds.), Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach (pp. 32–68). London: Blackwell.

Lin, N., & Xie, W. (1988). Occupational prestige in urban China. American Journal of Sociology 93, 793–832.

Low, B. S. (2000a). Why Sex Matters: A Darwinian Look at Human Behavior. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Low, B. S. (2000b). Sex, wealth, and fertility: Old rules, new environments. In L. Cronk, N. Chagnon, & W. Irons (Eds.), Adaptation and Human Behavior: An Anthropological Perspective (pp. 323-344). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Low, B. S., Clarke, A. L., and Lockridge, K. A. (1992). Toward an ecological demography. Population and Development Review 18, 1–31.

MacArthur, R. H., and Wilson, E. O. (1967). The Theory of Island Biogeography. NJ: Princeton University Press.

Meisner, M. (1999). Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic. 3rd ed. New York: The Free Press.

Parish, W. (1984). Destratification in China. In J. Watson (Ed.), Class and Social Stratification in Post-Revolution China (pp. 84–120). MA: Cambridge University Press.

Peng, X. (1991). Demographic Transition in China: Fertility Trends since the 1950s. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Roff, D. A. (1992). The Evolution of Life Histories: Theory and Analysis. New York: Chapman and Hall.

Scharping, T. (2003). Birth Control in China 1949-2000. London: Routeledge Curzon.

Schoppa, R. K. (2002). Revolution and its Past: Identities and Change in Modern Chinese History. NJ: Prentice Hall.

State Statistical Bureau (1986). China In-Depth Fertility Survey. Principal Report, Vols 1 & 2. Department of Population Statistics of the State Statistical Bureau, Beijing.

Stearns, S. C. (1992). The Evolution of Life History. Oxford University Press.

Stockman, N. (2000). Understanding Chinese Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ting, T.-F. 2003. Human reproductive ecology in revolutionary China. PhD Dissertation. University of Michigan.

Wang, G. (2000). The distribution of China's population and its changes. In X. Peng & Z. Guo (Eds.), The Changing Population of China (pp. 11–19). London: Blackwell.

Willis, R. J. (1973). A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy (March-April), S14–S64.

Zhou, X., Moen, P., & Tuma, N. B. (1998). Educational stratification in urban China: 1949-94. Sociology of Education 71, 199–222.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ting, TF. Resources, Fertility, and Parental Investment in Mao's China. Population and Environment 25, 281–297 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POEN.0000036481.07682.7e

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POEN.0000036481.07682.7e