Abstract

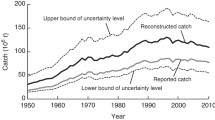

Catches of whales show a historically cyclical pattern, with catches declining as stocks of the financially most attractive species fell, but expanding as substitute species were caught. Total combined catch peaked in the early 1960s and fell thereafter to the current regulated levels. While it is widely thought that international whaling agreements account for the current stable stock levels, economic analysis reveals that market forces leading to reduced catch were already in place well before the agreements took hold. To some extent, therefore, catches were destined to decline as whale products ceased to be commercially attractive on a large scale. Using econometric analysis, the paper shows the various forces at work: declining stocks, the rise of substitute products, internationally increasing environmentalism, and rising incomes. Of these forces, stock decreases, which resulted in high unit catch costs, and income growth, which reduced rather than increased demand, were the most important factors, with regulation following, rather than leading, catch changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barrett S. 1994. Self-enforcing international environmental agreements. Oxford Economic Papers 46: 878–894.

Birnie P.W. 1989. International legal issues in the management and protection of the whale: a review of four decades of experience. Natural Resource Journal 29: 903–933.

Bockstoce J.R. and Botkin D.B. 1983. The historical status and reduction of theWestern Arctic Bowhead whale (Baleana mysticetus) population by the pelagic whaling industry, 1848-1914. In: Tillman M.F. and Donovan G.P. (eds), Reports of the International Whaling Commission: Special Issue 5 on Historical Whaling Records, Cambridge, pp. 107–142.

Chapman D.G. 1974. Estimation of population size and sustainable yield of sei whales. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 24: 82–90.

Clark C.W. 1973. Profit maximization and the extinction of animal species. Journal of Political Economy 81: 950–961.

Clark C.W. 1990. Mathematical Bioeconomics. 2nd edn. Wiley, New York.

DeLury D.B. 1947. On the estimation of biological populations. Biometrika 3: 467–480.

Duxbury A.C. and Duxbury A.B. 1991. An Introduction to the World's Oceans. Brown Publishers, Dubuque, Iowa.

Gulland J. 1988. The end of whaling? New Scientist 29th October: 1.

Leslie P.H and Davis D.H.S. 1939. An attempt to determine the absolute number of rats on a given area. Journal of Animal Ecology 8: 94–113.

Panayotou T. 1997. Demystifying the environmental Kuznets curve: turning a black box into a policy tool. Environment and Development Economics 2: 465–484.

The Committee for Whaling Statistics (Annual) International Whaling Statistics. Appointed by the Norwegian Government, Oslo, 1931-1984. Volumes I-XCII.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schneider, V., Pearce, D. What saved the whales? An economic analysis of 20th century whaling. Biodiversity and Conservation 13, 543–562 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BIOC.0000009489.08502.1a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BIOC.0000009489.08502.1a