Abstract

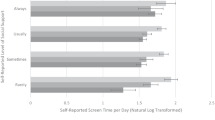

Quality of life (QOL) among Americans with diabetes was compared to Americans without diabetes using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System for 1996 through 2000. QOL was measured in terms of days in the last month of limited activity, poor physical health, poor mental health, pain, depression, stress, poor sleep, and high energy and perceived general health. Each of 42,154 diabetics was matched with one non-diabetic (control) respondent on age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Additional statistical adjustments were made for socio-economic status, marital status, and access to health care. Respondents with diabetes averaged more statistically adjusted impaired days than controls: 3.11 days (SE = 0.07) for physical health, 0.92 (SE = 0.06) for mental health, 1.69 (SE = 0.06) for limited activity, 1.86 (SE = 0.16) for pain, 1.14 (SE = 0.14) for depression, 1.11 (SE = 0.16) for stress, 1.47 (SE = 0.18) for inadequate rest or sleep, and 3.54 (SE = 0.21) fewer for high energy. General health was also lower. Diabetes compromised QOL a substantial proportion of time on every dimension tested. Across the board, lower education, being unable to work, unemployed, or retired and lacking funds to pay for needed medical care were associated with greater impairments among persons with diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andrews FM. Research on the Quality of Life. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research,University of Michigan, 1986.

Tarlov AR, Ware JE Jr, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perrin E, Zubko M. The Medical Outcomes Study. An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA 1989; 262(7): 925–930.

Ware JE Jr. The assessment of health status. In: Aiken LH, Mechanic D (eds), Applications of Social Science to Clinical Medicine and Health Policy, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press,1996: 204–228.

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD,et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: Results from the medical outcomes studyz.JAMA 1989; 262(7):907–913.(Erratum in JAMA 1989;262(18):2542).

Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of Life: Assessment, Analysis,and Interpretation. New York: John Wiley, 2000.

Staquet MJ, Hays RD, Fayers PM. Quality of Life Assessment in Clinical Trials:Methods and Practice. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000a.

The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL):Position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med 1995; 41(10): 1403–1409.

The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med 1998; 28(3): 551–558.

Skevington SM, Tucker C. Designing response scales for cross-cultural use in health care:Data from the development of the UK WHOQOL. Br J Med Psychol 1999; 72(Pt 1): 51–61.

Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 1999; 15: 205–218.

Wändell PE, Brorsson B, Åberg, H. Quality of life among diabetic patients in Swedish primary health care and in the general population:Comparison between 1992 and 1995. Qual Life Res 1998; 7: 751–760.

Valdmanis V, Smith DW, Page MR. Productivity and economic burden associated with diabetes in Oklahoma. The Am J Public Health 2001; 91(1): 129–130.

Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson, K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25(3): 464–470.

Parkerson GR Jr, Connis RT, Broadhead WE, Patrick DL, Taylor TR, Tse CK. Disease-specific versus generic measurement of health-related quality of life in insulin-dependent diabetic patients. Med Care 1993; 31(7): 629–639.

Gavard JA, Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Prevalence of depression in adults with diabetes. An epidemiological investigation. Diabetes Care 1993; 16(8): 1167–1178.

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001; 24(6): 1069–1078.

Talbot F, Nouwen A. A review of the relationship between depression and diabetes in adults:Is there a link? Diabetes Care 2000; 23(10): 1556–1562.

Sridhar GR, Madhu K. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Practice 1994; 23(3): 183–186.

Westaway MS, Rheeder P, Gumede T. The effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Curationis 2001; 24(1): 74–78.

McFall SM, Solomon TGA, Smith DW. Health related quality of life of older American Indian primary care patients. Res Aging 2000; 22(6): 692–714.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2000.

Hennessy CH, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Scherr PA, Brackbill R. Measuring health-related quality of life for public health surveillance. Public Health Rep 1994; 109(5): 665–672.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.2000 BRFSS Summary Quality Control Report. October 24,2001.

Woolson RF, Lachenbruch PA. Regression analysis of matched case–control data. Am J Epidemiol 1982; 115: 444–452.

Centers for Disease Control. Racial and ethnic approaches to community health (REACH)2010.From CDC web site: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/aag/aag_reach.htm.Obtained on August 20,2003.

Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Fact Sheet: Diabetes disparities among racial and ethnic minorities. AHRQ Publication No.02-P007, November, 2001.

Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes,impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,1988–1994. Diabetes Care 1998; 21(4): 518–524.

Reed JS. Needles in Haystacks: Studying "Rare" Populations by Secondary Analysis of National Sample Surveys. Public Opin Quart 39(Winter 1975–76): 514–522.

Greenland S, Watson E, Neutra RR. The case–control method in medical care evaluation. Med Care 1981; 19(8): 872–878.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, D.W. The Population Perspective on Quality of Life among Americans with Diabetes. Qual Life Res 13, 1391–1400 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QURE.0000040785.59444.7c

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QURE.0000040785.59444.7c