Abstract

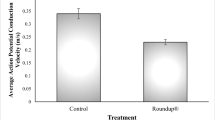

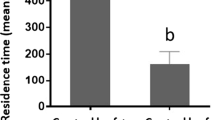

Larvae of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), often transect leaves with a narrow trench before eating the distal section. The trench reduces larval exposure to exudates, such as latex, during feeding. Plant species that do not emit exudate, such as Plantago lanceolata, are not trenched. However, if exudate is applied to a looper's mouth during feeding on P. lanceolata, the larva will often stop and cut a trench. Dissolved chemicals can be similarly applied and tested for effectiveness at triggering trenching. With this assay, I have documented that lactucin from lettuce latex (Lactuca sativa), myristicin from parsley oil (Petroselinum crispum), and lobeline from cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis) elicit trenching. These compounds are the first trenching stimulants reported. Several other constituents of lettuce and parsley, including some phenylpropanoids, monoterpenes, and furanocoumarins had little or no activity. Cucurbitacin E glycoside found in cucurbits, another plant family trenched by cabbage loopers, also was inactive. Lactucin, myristicin, and lobeline all affect the nervous system of mammals, with lobeline acting specifically as an antagonist of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. To determine if cabbage loopers respond selectively to compounds active at acetylcholine synapses, I tested several neurotransmitters, insecticides, and drugs with known neurological activity, many of which triggered trenching. Active compounds included dopamine, serotonin, the insecticide imidacloprid, and various drugs such as ipratropium, apomorphine, buspirone, and metoclopramide. These results document that noxious plant chemicals trigger trenching, that loopers respond to different trenching stimulants in different plants, that diverse neuroactive chemicals elicit the behavior, and that feeding deterrents are not all trenching stimulants. The trenching assay offers a novel approach for identifying defensive plant compounds with potential uses in agriculture or medicine. Cabbage loopers in the lab and field routinely trench and feed on plants in the Asteraceae and Apiaceae. However, first and third instar larvae enclosed on Lobelia cardinalis (Campanulaceae) failed to develop, even though the third instar larvae attempted to trench. Trenching ability does not guarantee effective feeding on plants with canal-borne exudates. Cabbage loopers must not only recognize and respond to trenching stimulants, they must also tolerate exudates during the trenching procedure to disable canalicular defenses.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 1998. An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants. Ann. MO. Bot. Gard. 85:531–553.

Anonymous 1989. Crop Protection Chemicals Reference. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Press, Paris.

Arena, J. M. 1970. Poisoning: Toxicology, Symptoms, Treatments. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois.

Aydar, E. and Beadle, D. J. 1999. The pharmacological profile of GABA receptors on cultured insect neurones. J. Insect Physiol. 45:213–219.

Basset, Y. and Novotny, V. 1999. Species richness of insect herbivore communities on Ficus in Papua New Guinea. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 67:477–499.

Becerra, J. X. 1994. Squirt-gun defense in Bursera and the chrysomelid counterploy. Ecology 75:1991–1996.

Becerra, J. X., Venable, D. L., Evans, P. H., and Bowers, W. S. 2001. Interactions between chemical and mechanical defenses in the plant genus Bursera and their implications for herbivores. Am. Zool. 41:865–876.

Benson, J. A. 1993. The electrophysiological pharmacology of neurotransmitter receptors on locust neuronal somata, pp. 390–413, in Y. Pichon (ed.). Comparative Molecular Neurobiology. Birkhäuser, Basel, Switzerland.

Berenbaum, M. R. 1990. Evolution of specialization in insect-umbellifer associations. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 35:319–343.

Berenbaum, M. and Neal, J. J. 1985. Synergism between myristicin and xanthotoxin, a naturally cooccurring plant toxicant. J. Chem. Ecol. 11:1349–1358.

Bernath, J. (Ed.)1998. Poppy: The Genus Papaver. Harwood Academic, Amsterdam.

Burrows, M. 1996. The Neurobiology of an Insect Brain. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Camm, E. L., Wat, C., and Towers, G. H. N. 1976. An assessment of the roles of furanocoumarins in Heracleum lanatum. Can. J. Bot. 54:2562–2566.

Carroll, C. R. and Hoffman, C. A. 1980. Chemical feeding deterrent mobilized in response to insect herbivory and counteradaptation in Epilachna tredecimnotata. Science. 209:414–416.

Casida, J. E. and Quistad, G. B. 1998. Golden age of insecticide research: Past, present, or future? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 43:1–16.

Chapman, R. F. 1995. Chemosensory regulation of feeding, pp. 101–136 in R. F. Chapman and G. de Boer (Eds.). Regulatory Mechanisms in Insect Feeding. Chapman and Hall, New York.

Clarke, A. R. and Zalucki, M. P. 2000. Foraging and vein-cutting behaviour of Euploea core corinna (W. S. Macleay) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) caterpillars feeding on latex-bearing leaves. Aust. J. Entomol. 39:283–290.

Cohen, R. W., Mahoney, D. A., and Can, H. D. 2002. Possible regulation of feeding behavior in cockroach nymphs by the neurotransmitter octopamine. J. Insect Behav. 15:37–50.

Crellin, J. K. and Philpott, J. 1990. Herbal Medicine Past and Present. II: A Reference Guide to Medicinal Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.

Cremlyn, R. J. 1991. Agrochemicals: Preparation and Mode of Action. Wiley, New York.

Detzel, A. and Wink, M. 1993. Attraction, deterrence or intoxication of bees (Apis mellifera) by plant allelochemicals. Chemoecology 4:8–18.

Dollahite, J. W. and Allen, T. J. 1962. Poisoning of cattle, sheep, and goats with Lobezla and Centaurium species. Southwest. Vet. 15:126–130.

Duke, J. A. 1985. CRC Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida.

Dussourd, D. E. 1993. Foraging with finesse: Caterpillar adaptations for circumventing plant defenses, pp. 92–131, in N. E. Stamp and T. M. Casey (Eds.). Caterpillars: Ecological and Evolutionary Constraints on Foraging. Chapman and Hall, New York.

Dussourd, D. E. 1997. Plant exudates trigger leaf-trenching by cabbage loopers, Trichoplusia ni. Oecologia 112:362–369.

Dussourd, D. E. 1999. Behavioral sabotage of plant defense: Do vein cuts and trenches reduce insect exposure to exudate? J. Insect Behav. 12:501–515.

Dussourd, D. E. and Denno, R. F. 1991. Deactivation of plant defense: Correspondence between insect behavior and secretory canal architecture. Ecology 72:1383–1396.

Dussourd, D. E. and Denno, R. F. 1994. Host range of generalist caterpillars: Trenching permits feeding on plants with secretory canals. Ecology 75:69–78.

Dussourd, D. E. and Hoyle, A. M. 2000. Poisoned plusiines: Toxicity of milkweed latex and cardenolides to some generalist caterpillars. Chemoecology 10:11–16.

Dwoskin, L. P. and Crooks, P. A. 2001. Competitive neuronal nicotinic receptor antagonists: A new direction for drug discovery. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298:395–402.

Dwoskin, L. P. and Crooks, P. A. 2002. A novel mechanism of action and potential use for lobeline as a treatment for psychostimulant abuse. Biochem. Pharmacol. 63:89–98.

Eichlin, T. D. and Cunningham, H. B. 1978. The Plusiinae (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) of America north of Mexico, emphasizing genitalic and larval morphology. US Dept. Agric. Tech. Bull. 1567:1–122.

Fahn, A. 1979. Secretory Tissues in Plants. Academic Press, New York.

Farrell, B. D., Dussourd, D. E., and Mitter, C. 1991. Escalation of plant defense: Do latex and resin canals spur plant diversification? Am. Nat.. 138:881–900.

Flint, M. L. 1987. Integrated Pest Management for Cole Crops and Lettuce. University of California, Publication No. 3307.

Florio, V., Fuentes, J. A., Ziegler, H., and Longo, V. G. 1972. EEG and behavioral effects in animals of some amphetamine derivatives with hallucinogenic properties. Behav. Biol. 7:401–414.

Fodor, G. B. and Colasanti, B. 1985. The pyridine and piperidine alkaloids: Chemistry and pharmacology, pp. 1–90, in S. W. Pelletier (ed.). Alkaloids: Chemical and Biological Perspectives, Vol. 3. Wiley, New York.

Foster, S. and Tyler, V. E. 1999. Tyler's Honest Herbal: A Sensible Guide to the Use of Herbs and Related Remedies. Haworth Herbal Press, New York.

Gershenzon, J. and Croteau, R. 1991. Terpenoids, pp. 165–219, in G. A. Rosenthal and M. R. Berenbaum (Eds.). Herbivores: Their Interactions with Secondary Plant Metabolites. Academic Press, New York.

Grimes, L. R. and Neunzig, H. H. 1986. Morphological survey of the maxillae in last-stage larvae of the suborder Ditrysia (Lepidoptera): Mesal lobes (Laciniogaleae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 79:510–526.

Gromek, D., Kisiel, W., Klodzinska, A., and Chojnacka-Wojcik, E. 1992. Biologically active preparations from Lactuca virosa L. Phytother. R. 6:285–287.

Guha, J. and Sen, S. P. 1975. The cucurbitacins—A review. Plant Biochem. J. 2:12–28.

Gupta, R. N. and Spenser, I. D. 1971. Biosynthesis of lobinaline. Can. J. Chem. 49:384–397.

Hallstrom, H. and Thuvander, A. 1997. Toxicological evaluation of myristicin. Nat. Toxins 5:186–192.

Harborne, J. B. and Baxter, H. 1993. Phytochemical Dictionary: A Handbook of Bioactive Compounds from Plants. Taylor and Francis, Washington, DC.

Hardman, J. G. and Limbird, L. E. (Eds.) 1996. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Harrod, S. B., Dwoskin, L. P., Crooks, P. A., Klebaur, J. E., and Bardo, M. T. 2001. Lobeline attenuates d-methamphetamine self-administration in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298:172–179.

Hartmann, T. 1991. Alkaloids, pp. 79–121, in G. A. Rosenthal and M. R. Berenbaum (Eds.). Herbivores: Their Interactions with Secondary Plant Metabolites. Vol. I: The Chemical Participants. Academic Press, New York.

Hegnauer, R. 1971. Chemical patterns and relationships of Umbelliferae, pp. 267–277, in V. H. Heywood (ed.). The Biology and Chemistry of the Umbelliferae. Academic Press, New York.

Huang, Z. J., Kinghorn, A. D., and Farnsworth, N. R. 1982. Studies on herbal remedies. I: Analysis of herbal smoking preparations alleged to contain lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) and other natural products. J. Pharm. Sci. 71:270–271.

Jolivet, P. 1998. Interrelationship Between Insects and Plants. CRC Press, New York.

Kindscher, K. 1992. Medicinal Wild Plants of the Prairie: An Ethnobotanical Guide. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansasy.

Kingsbury, J. M. 1964. Poisonous Plants of the United States and Canada. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Knogge, W., Kombrink, E., Schmelzer, E., and Hahlbrock, K. 1987. Occurrence of phytoalexins and other putative defense-related substances in uninfected parsley plants. Planta 171:279–287.

Krochmal, A., Wilken, L., and Chien, M. 1972. Lobeline content of four Appalachian Lobelias. Lloydia 35:303–304.

Kubeczka, K. H. and Stahl, E. 1977. On the essential oils from the Apiaceae (Umbelliferae). II: The essential oils from the above ground parts of Pastinaca sativa. Planta Med. 31:173–184.

Lafontaine, J. D. and Poole, R. W. 1991. Noctuoidea, noctuidae (part), in R. B. Dominick et al. (Eds.). The Moths of America North of Mexico, Fasc. 25.1. Wedge Entomological Research Foundation, Washington, DC.

Lavy, G. 1987. Nutmeg intoxication in pregnancy: A case report. J. Reprod. Med. 32:63–64.

Lewinsohn, T. M. 1991. The geographical distribution of plant latex. Chemoecology 2:64–68.

Lewis, A. C. 1984. Plant quality and grasshopper feeding: Effects of sunflower condition on preference and performance in Melanoplus differentialis. Ecology 65:836–843.

Lichtenstein, E. P. and Casida, J. E. 1963. Myristicin, an insecticide and synergist occurring naturally in the edible parts of parsnips. J. Agric. Food Chem. 11:410–415.

Lichtenstein, E. P., Liang, T. T., Schulz, K. R., Schnoes, H. K., and Carter, G. T. 1974. Insecticidal and synergistic components isolated from dill plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 22:658–664.

Long, T. F. and Murdock, L. L. 1983. Stimulation of blowfly feeding behavior by octopaminergic drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80:4159–4163.

Macleod, A. J., Snyder, C. H., and Subramanian, G. 1985. Volatile aroma constituents of parsley leaves. Phytochemistry 24:2623–2627.

Marston, A., Hostettmann, K., and Msonthi, J. D. 1995. Isolation of antifungal and larvicidal constituents of Diplolophium buchanani by centrifugal partition chromatography. J. Nat. Prod. 58:128–130.

Matsuda, K., Buckingham, S. D., Kleier, D., Rauh, J. J., Grauso, M., and Sattelle, D. B. 2001. Neonicotinoids: Insecticides acting on insect nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 22:573–580.

Mccloud, E. S., Tallamy, D. W., and Halaweish, F. T. 1995. Squash beetle trenching behaviour: Avoidance of cucurbitacin induction or mucilaginous plant sap? Ecol. Entomol. 20:51–59.

Metcalf, R. L., Metcalf, R. A., and Rhodes, A. M. 1980. Cucurbitacins as kairomones for diabroticite beetles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:3769–3772.

Metcalfe, C. R. and Chalk, L. 1983. Anatomy of the Dicotyledons, Vol. II. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Mullin, C. A., Alfatafta, A. A., Harman, J. L., Everett, S. L., and Serino, A. A. 1991. Feeding and toxic effects of floral sesquiterpene lactones, diterpenes, and phenolics from sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) on western corn rootworm. J. Agric. Food Chem. 39:2293–2299.

Mullin, C. A., Chyb, S., Eichenseer, H., Hollister, B., and Frazier, J. L. 1994. Neuroreceptor mechanisms in insect gustation: A pharmacological approach. J. Insect Physiol. 40:913–931.

Murdock, L. L., Brookhart, G., Edgecomb, R. S., Long, T. F., and Sudlow, L. 1985. Do plants “psychomanipulate” insects? pp. 337–351, in P. A. Hedin (ed.). Bioregulators for Pest Control. ACS Symposium Series 276. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC.

Nauen, R., Ebbinghaus-kintscher, U., Elbert, A., Jeschke, P., and Tietjen, K. 2001. Acetylcholine receptors as sites for developing neonicotinoid insecticides, pp. 77–105, in I. Ishaaya (ed.). Biochemical Sites of Insecticide Action and Resistance. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Neal, J. J. 1989. Myristicin, safrole, and fagaramide as phytosynergists of xanthotoxin. J. Chem. Ecol. 15:309–315.

Oliver, F., Amon, E. U., Breathnach, A., Francis, D. M., Sarathchandra, P., Kobza black, A., and Greaves, M. W. 1991. Contact urticaria due to the common stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)—Histological, ultrastructural and pharmacological studies. Clin. Exp. Derm. 16:1–7.

Osborne, R. H. 1996. Insect neurotransmission: Neurotransmitters and their receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 69:117–142.

Palumbo, J., Mullis, C., Jr., Reyes, F., and Amaya, A. 1997. Evaluation of foliar insecticide approaches for aphid management in head lettuce, pp. 171–177, in N. F. Oebker (ed.). 1997 Vegetable Report. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona.

Picman, A. K. 1986. Biological activities of sesquiterpene lactones. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 14:255–281.

Porter, N. G. 1989. Composition and yield of commercial essential oils from parsley. 1: Herb oil and crop development. Flav. Frag. J. 4:207–219.

Price, K. R., Dupont, M. S., Shepherd, R., Chan, H. W., and Fenwick, G. R. 1990. Relationship between the chemical and sensory properties of exotic salad crops—Coloured lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and chicory (Cichorium intybus). J. Sci. Food Agric. 53:185–192.

Pytte, M. and Rygnestad, T. 1998. Nutmeg intoxication—A case report. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 118:4346–4347.

Rees, S. B. and Harborne, J. B. 1985. The role of sesquiterpene lactones and phenolics in the chemical defense of the chicory plant. Phytochemistry 24:2225–2231.

Rehm, S., Enslin, P. R., Meeuse, A. D. J., and Wessels, J. H. 1957. Bitter principles of the Cucurbitaceae. VII: The distribution of bitter principles in this plant family. J. Sci. Food Agric. 8:679–691.

Reinold, S. and Hahlbrock, K. 1997. In situ localization of phenylpropanoid biosynthetic mRNAs and proteins in parsley (Petroselinum crispum). Bot. Acta 110:431–443.

Reitz, S. R. and Trumble, J. T. 1996. Tritrophic interactions among linear furanocoumarins, the herbivore Trichoplusia ni (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), and the polyembryonic parasitoid Copidosoma floridanum (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae). Environ. Entomol. 25:1391–1397.

Roberts, M. F., Mccarthy, D., Kutchan, T. M., and Coscia, C. J. 1983. Localization of enzymes and alkaloidal metabolites in Papaver latex. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 222:599–609.

Roeder, T. 1994. Biogenic amines and their receptors in insects. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 107C:1–12.

Roshchina, V. V. 2001. Neurotransmitters in Plant Life. Science Publishers, Enfield, New Hampshire.

Sattelle, D. B. 1985. Acetylcholine receptors, pp. 395–434, in G. A. Kerkut and L. I. Gilbert (Eds.). Comprehensive Insect Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology. Vol. 11: Pharmacology. Pergamon Press, New York.

Schenck, G. 1966. Pharmacology of nitrogen-free bitter principles of Lactuca virosa: Destruction of these substances during extraction and drying, pp. 112–117, in G. S. Sidhu, I. K. Kacker, P. B. Sattur, G. Thyagarajan, and V. R. K. Paramahamsa (Eds.). CNS Drugs: A Symposium Held at the Regional Research Laboratory Hyderabad, India, January 24–30, 1966. Sree Saraswaty Press, Calcutta, India.

Sessa, R. A., Bennett, M. H., Lewis, M. J., Mansfield, J. W., and Beale, M. H. 2000. Metabolite profiling of sesquiterpene lactones from Lactuca species. J. Biol. Chem. 275:26877–26884.

Simon, J. E. and Quinn, J. 1988. Characterization of essential oil of parsley. J. Agric. Food Chem. 36:467–472.

Srivastava, S., Gupta, M. M., Prajapati, V., Tripathi, A. K., and Kumar, S. 2001. Insecticidal activity of myristicin from Piper mullesua. Pharm. Biol. 39:226–229.

Stahl-biskup, E. and Wichtmann, E. M. 1991. Composition of the essential oils from roots of some Apiaceae in relation to the development of their oil duct systems. Flav. Frag. J. 6:249–255.

Steelink, C., Yeung, M., and Caldwell, R. L. 1967. Phenolic constituents of healthy and wound tissues in the giant cactus (Carnegiea gigantea). Phytochemistry 6:1435–1440.

Stephens, H. A. 1980. Poisonous Plants of the Central United States. Regents Press of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

Stevens, W. C. 1948. Kansas Wild Flowers. University of Kansas Press, Lawrence.

Sutherland, D. W. S. and Greene, G. L. 1984. Cultivated and wild host plants. US Dept. Agric. Tech. Bull. 1684:1–13.

Tallamy, D. W. 1985. Squash beetle feeding behavior: An adaptation against induced cucurbit defenses. Ecology 66:1574–1579.

Tallamy, D. W., Stull, J., Ehresman, N. P., Gorski, P. M., and Mason, C. E. 1997. Cucurbitacins as feeding and oviposition deterrents to insects. Environ. Entomol. 26:678–683.

Tamaki, H., Robinson, R. W., Anderson, J. L., and Stoewsand, G. S. 1995. Sesquiterpene lactones in virus-resistant lettuce. J. Agric. Food Chem. 43:6–8.

Thomson, W. T. 1998. Agricultural Chemicals Book. I: Insecticides, Acaricides and Ovicides. Thomson, Fresno, California.

Tibbitts, T. W. and Read, M. 1976. Rate of metabolite accumulation into latex of lettuce and proposed association with tipburn injury. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 101:406–409.

Trimmer, B. A. 1995. Current excitement from insect muscarinic receptors. TINS 18:104–111.

Truitt, E. B., Jr. 1979. The pharmacology of myristicin and nutmeg, pp. 215–222, in D. H. Efron, B. Holmstedt, and N. S. Kline (Eds.). Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs. Raven Press, New York.

Truitt, E. B., Jr., Callaway, E., Braude, M. C., and Krantz, J. C., Jr. 1961. The pharmacology of myristicin: A contribution to the psychopharmacology of nutmeg. J. Neuropsychiatry 2:205–210.

Tune, R. and Dussourd, D. E. 2000. Specialized generalists: Constraints on host range in some plusiine caterpillars. Oecologia 123:543–549.

Watling, K. J. 1998. The RBI Handbook of Receptor Classification and Signal Transduction. RBI, Natick, Massachusetts.

Wink, M. 1998. Modes of action of alkaloids, pp. 301–326, in M. F. Roberts and M. Wink (Eds.). Alkaloids: Biochemistry, Ecology, and Medicinal Applications. Plenum, New York.

Wink, M. and Schneider, D. 1990. Fate of plant-derived secondary metabolites in three moth species (Syntomis mogadorensis, Syntomeida epilais, and Creatonotos transiens). J. Comp. Physiol. B 160:389–400.

Wu, S. and Hahlbrock, K. 1992. In situ localization of phenylpropanoid-related gene expression in different tissues of light-and dark-grown parsley seedlings. Z. Naturforsch.. 47c:591–600.

Zalucki, M. P., Clarke, A. R., and Malcolm, S. B. 2002. Ecology and behavior of first instar larval Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47:361–393.

Zangerl, A. R. 1990. Furanocoumarin induction in wild parsnip: Evidence for an induced defense against herbivores. Ecology 71:1926–1932.

Zangerl, A. R. and Bazzaz, F. A. 1992. Theory and pattern in plant defense allocation, pp. 363–391, in R. S. Fritz and E. L. Simms (Eds.). Plant Resistance to Herbivores and Pathogens: Ecology, Evolution and Genetics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dussourd, D.E. Chemical Stimulants of Leaf-Trenching by Cabbage Loopers: Natural Products, Neurotransmitters, Insecticides, and Drugs. J Chem Ecol 29, 2023–2047 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025630301162

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025630301162