Abstract

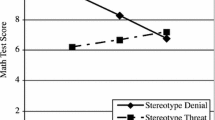

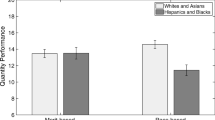

This study was designed to examine the different ways that stereotypes might become activated in testing situations and the effects this activation has on task performance. In Experiment 1, women undergraduates exposed to an explicitly activated stereotype (i.e., told men outperform women in mathematics) performed worse than women exposed to a nullified stereotype (i.e., told men and women perform at the same level in mathematics). The stereotype threat also was activated implicitly under “normal” conditions (i.e., just given the test with nothing else stated) such that performance in this condition was at the same (low) level as the explicitly activated threat. In Experiment 2, the results were replicated with White male undergraduates using the stereotype that “Asians are better than Whites” in mathematics. In addition, in a small field survey we found that this belief about ethnicity did occur spontaneously for White men in college calculus courses. Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that even under normal circumstances, math test situations may lead to nonoptimal performance for both stigmatized (women) and traditionally nonstigmatized (White men) group members. Implications for threat nullification techniques are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Allport, G. (1954/1979). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

American Association of University Women. (1992). How schools shortchange girls: The AAUW report: Astudy of major findings on girls in education. Washington, DC: American Association of University Women Educational Foundation.

Aronson, J., Lustina, M. J., Good, C., Keough, K., Steele, C. M., & Brown, J. (1999). When White men can't do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 29-46.

Aronson, J., Quinn, D. M., & Spencer, S. J. (1998). Stereotype threat and the academic underperformance of minorities and women. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target's perspective (pp. 83-103). New York: Academic Press.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Benbow, C. P., Lubinski, D., Shea, D. L., & Eftekhari-Sanjani, H. (2000). Sex differences in mathematical reasoning ability at age 13: Their status 20 years later. Psychological Science, 11, 474-480.

Benbow, C. P., & Stanley, J. C. (1980). Sex differences in mathematical ability: Fact or artifact? Science, 210, 1262-1264.

Benbow, C. P., & Stanley, J. C. (1983). Sex differences in mathematical reasoning ability: More facts. Science, 222, 1029-1031.

Betz, N. E., & Hackett, G. (1981). The relationship of career-related self-efficacy expectations to perceived career options in college women and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 28, 399-410.

Brandon, K. (1992, October 22). Barbie's banter just adds to math minuses for girls. Chicago Tribune, p. D16.

Brown, R. P., & Josephs, R. A. (1999). A burden of proof: Stereo-type relevance and gender differences in math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 246-257.

Bryan, T., & Bryan, J. (1991). Positive mood and math performance. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 24, 490-494.

Cacioppo, J. T., Gardner, W. L., & Berntson, G. G. (1997). Beyond bipolar conceptualizations and measures: The case of attitudes and evaluative space. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 1, 3-25.

Cacioppo, J. T., Harkins, S. G., & Petty, R. E. (1981). The nature of attitudes and cognitive responses and their relationships to behavior. In R. Petty, T. Ostrom, & T. Brock (Eds.), Cognitive responses in persuasion (pp. 31-54). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Crocker, J., Major, B., & Steele, C. (1998). Social stigma. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, 4th ed., pp. 504-553). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Croizet, J. C., & Claire, T. (1998). Extending the concept of stereo-type threat to social class: The intellectual underperformance of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 588-594.

Eccles, J. (1984). Sex differences in achievement patterns. In T. B. Sonderegger (Ed.), Psychology and gender: Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 32, pp. 97-132). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Eccles, J. S. (1994). Understanding women's educational and occupational choices: Applying the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 585-609.

Eccles, J. S., Adler, T., & Meece, J. L. (1984). Sex differences in achievement: A test of alternate theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 26-43.

Educational Testing Service. (1996). Practicing to take the general test: Big book. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Farmer, H. S. (1997). Women's motivation related to mastery, career salience, and career aspiration: A multivariate model focusing on the effects of sex role socialization. Journal of Career Assessment, 5, 355-381.

Gaertner, S., & Dovidio, J. (1986). The aversive form of racism. In S. Gaertner & J. Dovidio (Eds.), Prejudice, discrimination, and racism (pp. 61-89). New York: Academic Press.

Gilbert, D. T., & Hixon, J. G. (1991). The trouble of thinking: Activation and application of stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 509-517.

Glass, G. V., Peckham, P. D., & Sanders, J. R. (1972). Consequences of failure to meet assumptions underlying the fixed-effects analysis of variance and covariance. Review of Educational Research, 42, 237-288.

Grandy, J. (1994). Gender and ethnic differences among science and engineering majors: Experiences, achievements, and expectations (GRE board research report No 92-03R, ETS research report 94-30). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Herrnstein, R. J., & Murray, C. A. (1994). The bell curve: Intelligence and class structure in American life. New York: Free Press.

Hyde, J. S., Fennema, E., & Lamon, S. J. (1990). Gender differences in mathematics performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 139-155.

Ito, T. A., Larsen, J. T., Smith, N. K., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1998). Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: The negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 887-900.

Jacobs, J. E., & Eccles, J. S. (1992). The impact of mothers' gender-role stereotypic beliefs on mothers' and children's ability perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 932-944.

Jones, J. M. (1997). Prejudice and racism (2nd ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Kimball, M. M. (1998). Gender and math: What makes a difference? In D. L. Anselmi & A. L. Law (Eds.), Questions of gender: Perspectives and paradoxes (pp. 446-460). Boston: McGraw Hill.

Kunda, Z., & Oleson, K. (1995). Maintaining stereotypes in the face of disconfirmation: Constructing grounds for subtyping deviants. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 565-579.

LeFevre, J. A., Kulak, A. G., & Heymans, S. L. (1992). Factors influencing the selection of university majors varying in mathematical content. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 24, 276-289.

Leyens, J. P., Désert, M., Croizet, J. C., & Darcis, C. (2000). Stereo-type threat: Are lower status and history of stigmatization pre-conditions of stereotype threat? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1189-1199.

Maurer, K. L., Park, B., & Rothbart, M. (1995). Subtyping versus subgrouping processes in stereotype representation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 812-824.

Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard, T. J., Jr., Boykin, A. W., Brody, N., Ceci, S. J., et al. (1996). Intelligence: Knownsand unknowns. American Psychologist, 51, 77-101.

Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). Math = male, me = female, therefore math ≠ me. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 44-59.

Quinn, D. M., & Spencer, S. J. (2001). The interference of stereotype threat with women's generation of mathematical problem-solving strategies. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 55-71.

Renninger, K. A. (2000). How might the development of individual interest contribute to the conceptualization of intrinsic motivation? In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 375-407). New York: Academic Press.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1966). Teachers' expectancies: Determinants of pupils' IQ gains. Psychological Reports, 19, 115-118.

Seymour, E. (1995). The loss of women from science, mathematics, and engineering undergraduate majors: An explanatory account. Science Education, 79, 437-473.

Shih, M., Pittinsky, T. L., & Ambady, N. (1999). Stereotype susceptibility: Identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychological Science, 10, 80-83.

Smart, L., & Wegner, D. M. (2000). The hidden costs of hidden stigma. In T. F. Heatherton, R. E. Kleck, M. R. Hebl, & J. G. Hull (Eds.), The social psychology of stigma (pp. 220-242). New York: Guilford Press.

Smith, J. L., & White, P. H. (2001). Development of the domain identification measure: A tool for investigating stereotype threat effects. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61, 1040-1057.

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women's math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 4-28.

Stangor, C., Carr, C., & Kiang, L. (1998). Activating stereotypes undermines task performance expectations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1191-1197.

Stangor, C., & Sechrist, G. B. (1998). Conceptualizing the determinants of academic choice and task performance across social groups. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target's perspective (pp. 105-124). New York: Academic Press.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52, 613-629.

Steele, C. M. (1999, August). Thin ice: Stereotype threat and Black college students. Atlantic Monthly, pp. 44-54.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African-Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797-811.

Steen, L. A. (1987). Mathematics education: A predictor of scientific competitiveness. Science, 237, 251-253.

Stevenson, H. W., Chen, C., & Lee, S. Y. (1993). Mathematics achievement of Chinese, Japanese, and American children: Ten years later. Science, 259, 53-58.

Stone, J., Lynch, C. I., Sjomeling, M., & Darley, J. M. (1999). Stereo-type threat effects on Black and White athletic performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1213-1227.

Sue, S., & Okazaki, S. (1990). Asian American educational achievements. American Psychologist, 45, 913-920.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070.

Weber, R., & Cracker, J. (1983). Cognitive processes in the revision of stereotypic beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 961-977.

Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101, 34-52.

Word, C. O., Zanna, M., & Cooper, J. (1974). The nonverbal mediation of self-fulfilling prophecies in interracial interaction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 109-120.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, J.L., White, P.H. An Examination of Implicitly Activated, Explicitly Activated, and Nullified Stereotypes on Mathematical Performance: It's Not Just a Woman's Issue. Sex Roles 47, 179–191 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021051223441

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021051223441