Abstract

Over the past decade, several glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists have been developed and tested clinically as adjuncts to coronary intervention and/or treatment of acute coronary syndromes. Thrombocytopenia associated with this class of compounds has been described in most large studies to date and when it occurs in combination with bleeding represents a major safety concern. Cases of thrombocytopenia caused by GP IIb/IIIa antagonists vary in their clinical presentation according to time of onset (following the first dose or delayed), severity (profound, i.e., <20,000 cells/mm3, or mild), and may or may not be associated with clinically important bleeding. More than one etiology appears responsible for thrombocytopenia associated with GP IIb/IIIa antagonists, including acute, idiosyncratic, as well as delayed immune-mediated mechanisms. Comparison of the incidence of thrombocytopenia across the different agents currently being studied and the one agent commercially available is complicated by varying definitions of thrombocytopenia used to date; different clinical settings in which GP IIb/IIIa antagonists have been studied; use of concomitant medications such as heparin, which itself may cause thrombocytopenia; relatively infrequent occurrence of thrombocytopenia; and the limited number of patients exposed to these agents. Review of the large studies presented and published to date suggests that thrombocytopenia due specifically to GP IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists occurs in less than 5% of treated patients and may vary depending on the type of agent, concomitant therapy, and clinical scenario. Current standard management includes immediate cessation of the GP IIb/IIIa antagonist and, in severe cases, platelet transfusions. In cases with associated hemorrhage, other anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents should be discontinued and possibly reversed. There may be a role for IV IgG and steroids, especially for cases of thrombocytopenia that are immune-mediated; however, further investigations are necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Graves EJ, Gillum BS. 1994 Summary: National Hospital Discharge Survey. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics: no. 278. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 1996.

Harrington RA, Sane DC, Califf RM, et al. for the Thrombolysis and Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Clinical importance of thrombocytopenia occurring in the hospital phase after administration of thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994:23:891–898.

Selling L. A preliminary report of some cases of purpura hemorrhagica due to benzol poisoning. Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull 1910:21:33.

Ackroyd JF. The pathogenesis of thrombocytopenic purpura due to hypersensitivity to sedermoid. Clin Sci 1949:7: 249–248.

Miescher P, Cooper N. The fixation of soluble antigen-antibody complexes upon thrombocytes. Vox Sang 1960: 5138–5142.

Schulman NR. Immunoreactions involving platelets. IV. Studies on the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia in drug purpura using test doses of quinidine in sensitized individuals: Their implications in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Exp Med 1958:17:711–729.

Denning H. Thrombopenische purpura nach iodeinnahme. Munch Med Wsch 1933:80:562.

Trimble MS, Warkentin TE, Kelton JG. Thrombocytopenia due to platelet destruction and hypersplenism. In: Hoffman R, ed. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1991:1501–1513.

Gruel Y, Lang M, Darnige L, et al. Fatal effect of re-exposure to heparin after previous heparin-associated thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. Lancet 1990:336:1077–108.

Chong BH. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood Rev 1988:2:108–114.

Chong BH. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol 1995:89:431–439.

Warkentin TE, Kelton JG. Heparin and platelets. Hema Oncol Clin North Am 1990:4:243–264.

Hirsh J, Raschke R, Warkentin TE, Dalen J, Deykin D, Poller L. Heparin: Mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing considerations, monitoring, efficacy and safety. Chest 1995:108(Suppl.):258S–275S.

Babcock RB, Dumper CW, Scharfman WB. Heparin-induced immune thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 1976:295:237.

Cimo PL, Moake JL, Weinger RS, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: Association with a platelet-aggregating factor and arterial thromboses. Am J Metabol 1979:6:125.

Turpie AGG. The pharmacology of low-molecular weight heparin. The International Cardiology Forum Presents — Revisiting the standard of care: The emerging role of low-molecular-weight heparin in cardiology practice. Presented at American College of Cardiology 46th Annual Scientific Sessions, Anaheim, CA, March 15, 1997.

Aburahma AF, Boland JP, Witsberger T. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies of white clot syndrome. Am J Surg 1991:162:175–179.

Hirsh J. Heparin. N Engl J Med 1991:320:1565–1574.

Stanton PE, Evans JR, Lefemine AA, et al. White clot syndrome. Southern Med J 1988:81:616–620.

Scheinberg IH. Thrombocytopenic reaction to aspirin and acetaminophen. N Engl J Med 1979:300:678.

Garg SK, Sarker CR. Aspirin-induced thrombocytopenia on an immune basis. Am J Med Sci 1974:267:129–32.

Nieweg HO, Bouma HGD, Vries KD, et al. Hematological side effects of some antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 1963:22:440–443.

D'Eshouges JR, Griguer P, Smadja A, et al. Purpura thrombocytopenique aigu apr sensibilisation a l'aspirine. Nouv Rev Franc Hematol 1961:1:609–611.

Class FHJ, de Fraiture WH, Meyboom RHB. Thrombopénie causée par des anticorps induits par la ticlopidine. Nouv Rev Franc Hematol 1984:26:323–324.

Takeshita S, Kawazie N, Yoshida T, Fukiuama K. Ticlopidine and thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 1990:323:1487.

Kleiman NS, Ohman EM, Califf RM, et al. Profound inhibition of platelet aggregation with monoclonal antibody 7E3 Fab after thrombolytic therapy: Results of the Thrombolysis And Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (TAMI) 8 pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993:22:381–389.

Lincoff AM, Tcheng JE, Bass TA, et al. for the PROLOG Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995:00(Suppl.):80A–81A.

EPIC Investigators. Use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor in highrisk coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med 1994:330:956–961.

CAPTURE Investigators. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of abciximab before and during coronary intervention in refractory unstable angina: The CAPTURE study. Lancet 1997:349:1429–1435.

EPILOG Investigators. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade and low-dose heparin during percutaneous coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 1997:336: 1689–1696.

Berkowitz SD, Sane DC, Shavender JH, Sigmon KN, Toopol EJ, Califf RM, for the Evaluation of 7E3 for the Prevention of Ischemic Complications (EPIC) study group. Analysis of the occurrence and clinical significance of thrombocytopenia with c7E3 (abciximab) in the EPIC trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996:00(Suppl: A):82A.

Boehrer JD Kereiakes DJ, Navetta FI, Califf RM, Topol EJ for the EPIC Investigators. Effects of profound platelet inhibition with c7E3 before coronary angioplasty on complications of coronary bypass surgery. Am J Cardiol 1994:74: 1166–1170.

Keriekas DJ, Essell J, Abbottsmith CE Broderick TM, Runyon JP. Abciximab-associated profound thrombocytopenia: Therapy with immunoglobulin and platelet transfusion. Am J Cardiol 1996:78:1161–1163.

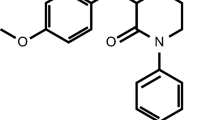

Egbertson MS, Chang CT, Duggan ME, et al. Non-peptide fibrinogen receptor antagonists 2. Optimization of a tyrosine template as a mimic for Arg-Gly-Asp. J Med Chem 1994:37: 2537–2551.

Keriekas DJ Kleiman NS, Ambrose J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled dose-ranging study of tirofiban (MK-383) platelet IIb/IIIa blockage in high risk patients undergoing coronary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996:27:536–542.

Anderson HV, Betrand ME, Whitworth HB, Sax FL, Willerson JT, for the RESTORE Investigators. Bleeding risk with platelet inhibition using tirofiban: The RESTORE trial. Circulation 1996:94(Suppl.):I553.

White HD for the PRISM Investigators. Platelet receptor inhibition for ischemic syndrome management (PRISM). Presented at American College of Cardiology 46th Annual Scientific Sessions, Anaheim, CA, March 17, 1997.

Theroux P for the PRISM-PLUS Investigators. GP IIb/IIIa antagonism with tirofiban in high risk unstable angina trial (PRISM-PLUS). Presented at American College of Cardiology 46th Annual Scientific Sessions, Anaheim, CA, March 17, 1997.

Ohman EM, Kleiman NS, Gacioch G, et al. for the IMPACTAMI Investigators. Combined accelerated tissue-plasminogen activator and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa integrin receptor blockage with integrilin in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1997:95:846–854.

Tcheng JE, Harrington RA, Kottke-Marchant K for the IMPACT Investigators. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the platelet integrin glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blocker integrelin in elective coronary intervention. Circulation 1995:91:2151–2157.

IMPACT-II Investigators. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of effect of eptifibatide on complications of percutaneous coronary intervention: IMPACT-II. Lancet 1997:349: 1422–1428.

Theroux P, Kouz S, Roy L et al. on behalf of the Investigators. Platelet membrane receptor glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonism in unstable angina: The Canadian lamifiban study. Circulation 1996:94:899–905.

Harrington RA, Newby LK, Moliterno DJ, et al. for the PARAGON Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997:29(Suppl. A):410A.

Cannon CP, Novotny WF, McCabe CH et al. for the TIMI 12 Investigators. Randomized trial of an oral glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist sibrafiban in patients after an acute coronary syndrome: Results of the TIMI 12 trial. Circulation 1998:97:340–349.

Theroux P, Kouz S, Knutdson ML et al. A randomized double-blind controlled trial with the non-peptidic platelet GP IIb/IIIa antagonist RO 44-9883 in unstable angina. Circulation 1994:90(Suppl. I):I232.

Simpfendorfer C, Kottke-Marchant K, Topol EJ. First experience with chronic platelet GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockage: A pilot study of xemilofiban an orally active antagonist in unstable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996:27:242A.

Kereiakes DJ, Runyon JP, Kleiman NS, et al. Differential dose-response to oral xemilofiban after antecedent intravenous abciximab. Circulation 1996:94:906–910.

White HD, Charbonnier B, Van deWerf F, et al. An aspirin-controlled study of MK-852 in patients with unstable angina. Circulation 1993:88(Suppl I.):I201.

Theroux P, Kleiman N, Shah PK, et al. A double-blind, heparin-controlled study of MK-852 in unstable angina. Circulation 1993:88(Suppl I.):I201.

Deedwania PC, Ferguson JJ, Kereiakes DJ, et al. Sustained platelet GP IIb/IIIa blockade with oral orbofiban: Interim safety and tolerability results of the SOAR study. J AmColl Cardio 1998:31(Suppl A):94A.

Giugliano RP, McCabe CH, Segueira RF, et al. Dose Ranging Study of Intravenous RPR 109891 in patients with acute coronary syndromes—results of TIMI 15A. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998:31(Suppl A):93A.

American Society of Hematology ITP Practice Guideline Panel. Diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: Recommendations of the American Society of Hematology. Ann Intern Med 1997:126:319–326.

Goebel RA. Thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Emerg 1993:11:445–464.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giugliano, R.P. Drug-Induced Thrombocytopenia: Is it a Serious Concern for Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Receptor Inhibitors?. J Thromb Thrombolysis 5, 191–202 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008887708104

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008887708104