Abstract

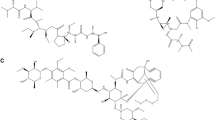

The review places podophyllotoxin, a powerful anti-cancer material used in clinical treatment of small cell cancers, in focus. The economical synthesis of podophyllotoxin is not feasible and demand for this material outstrips supply. At present, Podophyllum hexandrum (Indian May apple) is the commercial source but it grows in an inhospitable region (the Himalayas) where it is collected from wild stands. Furthermore, the plant is now an endangered species. Alternative sources of podophyllotoxin are considered, e.g., the supply of podophyllotoxin and related lignans by establishing plant cell cultures that can be grown in fermentation vessels. Increase of product yields, by variation of medium and culture conditions or by varying the channelling of precursors into side-branches of the biosynthetic pathway by molecular approaches, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andrews RC, Teague S J & Meyers AI (1988) Asymmetric total synthesis of (?)-podophyllotoxin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110: 7854–7858.

Arroo RRJ, Jacobs JJMR, de Koning AH, de Waard M, van de Westerloo E, et al. (1995) Thiophene interconversions in Tagetes patula hairy-root cultures. Phytochemistry 38: 1193–1197.

Arumugam N & Bhojwani SS (1990) Somatic embryogenesis in tissue cultures of Podophyllum hexandrum. Can. J. Bot. 68: 487–489.

Ayres DC & Loike JD (1990) Chemistry & Pharmacology of Natural Products. Lignans: Chemical, Biological and Clinical Properties. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Bastos JK, Burandt CL, Nanayakkara NPD, Bryant L & McChesney JD (1996) Quantitation of aryltetralin lignans in plant parts and among different populations of Podophyllum peltatum by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography. J. Nat. Prod. 59: 406–408.

Berkowitz D, Choi S & Maeng J (2000) Enzyme-assisted asymmetric total synthesis of (?)-podophyllotoxin and (?)-picropodophyllin. J. Org. Chem. 65: 847–860.

Bolwell GP, Bozak K & Zimmerlin A (1994) Plant cytochrome P450. Phytochemistry 37: 1491–1506.

Botta B, Delle Monache G, Misiti D, Vitali A & Zappia G (2001) Aryltetralin lignans: Chemistry, pharmacology and biotransformations. Curr. Med. Chem. 8: 1363–1381.

Broomhead AJ & Dewick PM (1990) Aryltetralin lignans from Linum flavum and Linum capitatum. Phytochemistry 29: 3839–3844.

Broomhead AJ, Rahman MMA, Dewick PM, Jackson DE & Lucas JA (1991) Biosynthesis of podophyllum lignans 5: Matairesinol as precursor of podophyllum lignans. Phytochemistry 30: 1489–1492.

Bush EJ & Jones DW (1995) Asymmetric total synthesis of (?)-podophyllotoxin. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1: 151–155.

Canel C, Moraes RM, Dayan FE & Ferreira D (2000) Molecules of interest: Podophyllotoxin. Phytochemistry 54: 115–120.

Chu A, Dinkova A, Davin LB, Bedgar DL & Lewis NG (1993) Stereospecificity of (+)-pinoresinol and (+)-lariciresinol reductases from Forsythia intermedia. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 27026–27033.

Cole JR & Wiedhopf RM 1978. Distribution. In: Rao CBS (ed) Chemistry of lignans (pp. 39–64). Andhra University Press, Andhra Pradesh.

Cragg GM & Newman DJ (2000) Antineoplastic agents from natural sources: Achievements and future directions. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 9: 2783–2797.

Cragg GM, Newman DJ & Snader KM (1997) Natural products in drug discovery and development. J. Nat. Prod. 60: 52–60.

Davin LB, Bedgar DL, Katayama T & Lewis NG (1992) On the stereoselective synthesis of (+)-pinoresinol in Forsythia suspensa from its achiral precursor, coniferyl alcohol. Phytochemistry 31: 3869–3874.

Davin LB & Lewis NG (2000) Dirigent proteins and dirigent sites explain the mystery of radical precursor coupling in lignan and lignin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 123: 453–461.

Dräger B, Portsteffen A, Schaal A, McCabe PH, Peerless ACJ & Robins RJ (1992) Levels of tropinone-reductase activities influence the spectrum of tropane esters found in transformed root cultures of Datura stramonium L. Planta 188: 581–586.

Fay DA & Ziegler HW (1985) Botanical source differentiation of podophyllum resin by HPLC. J. Liq. Chromatogr. 8: 1501–1505.

Fujita Y (1988) Industrial production of shikonin and berberine. CIBA Found. Symp. 137: 228–235.

Gupta R & Sethi KL (1983) Conservation of medicinal plant resources in the Himalayan region. In: Jain SK & Mehra KL (eds) Conservation of Tropical Plant Resources (pp. 101–107). Botanical Survey of India, Howrah.

Howarth RD (1936) Natural resins. Ann. Rep. Progr. Chem. 33: 266–279.

Jackson DE & Dewick PM (1984a) Biosynthesis of Podophyllum lignans 1: Cinnamic acid precursors of podophyllotoxin in Podophyllum hexandrum. Phytochemistry 23: 1029–1035.

Jackson DE & Dewick PM (1984b) Biosynthesis of Podophyllum lignans 2: Interconversions of aryltetralin lignans in Podophyllum hexandrum. Phytochemistry 23: 1037–1042.

Kamil WM & Dewick PM (1986a). Biosynthesis of Podophyllum lignans 3: Biosynthesis of the lignans ?-peltatin and ?-peltatin. Phytochemistry 25: 2089–2092.

Kamil WM & Dewick PM (1986b) Biosynthesis of Podophyllum lignans 4: Biosynthetic relationship of aryltetralin lactone lignans to dibenzylbutyrolactone lignans. Phytochemistry 25: 2093–2102.

Kuhlmann S, Kranz K, Lücking B, Alfermann AW & Petersen M (2002). Aspects of cytotoxic lignan biosynthesis in suspension cultures of Linum nodiflorum. Phytochemistry Reviews 1 (this issue).

Lewis NG, Davin LB, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Ford JD, Fujita M, Gang DR & Sarkanen S (1997) Recombinant pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase, recombinant dirigent protein, and methods of use. USA patent 09/475,316.

Mazur W & Adlercreutz H (1998) Naturally occurring oestrogens in food. Pure Appl. Chem. 70: 1759–1776.

Moraes RM, Burandt C, Ganzera M, Li XL, Khan I & Canel C (2000) The American mayapple revisited-Podophyllum peltatum-Still a potential cash crop? Econ. Bot. 54: 471–476.

Moraes-Cerdeira RM, Burandt CL, Bastos JK, Nanayakkara NPD & McChesney JD (1998) In vitro propagation of Podophyllum peltatum. Planta Med. 64: 42–45.

Moss GP (2000) Nomenclature of lignans and neolignans (IUPAC Recommendations 2000). Pure Appl. Chem. 72: 1493–1523.

Oksman-Caldentey KM & Hiltunen R (1996) Transgenic crops for improved pharmaceutical products. Field Crops Res. 45: 57–69.

Parr AJ, Walton NJ, Bensalem S, McCabe PH & Routledge W (1991) 8-Thiobicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-one as a biochemical tool in the study of tropane alkaloid biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 30: 2607–2609.

Potter GA, Patterson LH, Wanogho E, Perry PJ, Butler PC, Ijaz T, Ruparelia KC, Lamb J, Farmer PJ, Stanley LA & Burke MD (2002) The cancer preventative agent resveratrol is converted to the anticancer agent piceatannol by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1B1. Br. J. Cancer 86: 774–778.

Pras N, Woerdenbach HJ & van Uden W (1995) The power of plant enzymes in bioconversions. AgBiotech News Inform. 7: 231N–243N.

Ramos AC, Paláez R, López JL, Caballero E, Medarde M & San Feliciano A (2001) Heterolignanolides. Furo-and thienoanalogues of podophyllotoxin and thuriferic acid. Tetrahedron 57: 3963–3977.

Ramos AC, Peláez Lamamié de Clairac R & Medarde M (1999) Heterolignans. Heterocycles 51: 1443–1470.

Schuler MA (1996) Plant cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 15: 235–284.

Sharma TR, Singh BM, Sharma NR & Chauhan RS (2000) Identification of high podophyllotoxin producing biotypes of Podophyllum hexandrum Royle from North-Western Himalaya. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 9: 49–51.

Stähelin HF & von Wartburg A (1989) From podophyllotoxin to glucoside to etoposide. Progr. Drugs Res. 33: 169–266.

Stähelin HF & von Wartburg A (1991) The chemical and biological route from podophyllotoxin glucoside to etoposide: Ninth Cain memorial award lecture. Cancer Res. 51: 5–15.

Suzuki S, Umezawa T & Shimada M (1998) Stereochemical difference in secoisolariciresinol formation between cell-free extracts from petioles and from ripening seeds of Arctium lappa. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62: 1468–1470.

Suzuki S, Umezawa T & Shimada M (1999) Stereochemical selectivity in secoisolariciresinol formation by cell-free extracts from Arctium lappa L. ripening seeds. Wood Res. 86: 37–38.

Umezawa T, Davin LB & Lewis NG (1991) Formation of lignans (?)-secoisolariciresinol and (?)-matairesinol with Forythia intermedia cell-free extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 10210–10217.

Umezawa T & Shimada M (1996) Formation of the lignan (+)-secoisolariciresinol by cell-free extracts of Arctium lappa. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 60: 736–737.

van der Schouw YT, de Kleijn MJJ, Peeters PHM & Grobbee DE (2000) Phyto-oestrogens and cardiovascular disease risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 10: 154–167.

Van Uden W, Bouma AS, Waker JFB, Middel O, Wichers HJ, De Waard P, Woerdenbach HJ, Kellogg RM & Pras N (1995) The production of podophyllotoxin and its 5-methoxy derivative through bioconversion of cyclodextrin-complexed deoxy35 podophyllotoxin by plant-cell cultures Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 42: 73–79.

Van Uden W, Bos JA, Boeke GM, Woerdenbag HJ & Pras N (1997) The large-scale isolation of deoxypodophyllotoxin from rhizomes of Anthriscus sylvestris followed by its bioconversion into 5-methoxypodophyllotoxin beta-D-glucoside by cell cultures of Linum flavum J. Nat. Prod. 60: 401–403.

Venkat K, Bringi V, Kadkade P & Prince C (1997) Large scale production of secondary metabolites using plant cell cultures: Opportunities, realities and challenges. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 213: 54.

Ward RS (1997) Lignans, neolignans and related products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 14: 43–74.

Ward RS (1999) Lignans, neolignans and related products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 16: 75–96.

Xia ZQ, Costa MA, Proctor J, Davin LB & Lewis NG (2000) Dirigent-mediated podophyllotoxin biosynthesis in Linum flavum and Podophyllum peltatum. Phytochemistry 55: 537–549.

Yang CS, Landau JM, Huang MT & Newmark HL (2001) Inhibition of carcinogenesis by dietary polyphenolic compounds. Ann. Rev. Nutr. 21: 381–406.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arroo, R., Alfermann, A., Medarde, M. et al. Plant cell factories as a source for anti-cancer lignans. Phytochemistry Reviews 1, 27–35 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015824000904

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015824000904