Abstract

Introduction

Mobile messaging devices (MMD) have become common for communication in healthcare with the hope of improving accessibility of clinicians, efficiency, and response time. However, MMDs tend to increase messaging volume, contribute to clinician fatigue, and raise safety concerns. Our hypothesis was that targeted multi-professional education will reduce messaging volume and subjective burden on clinicians.

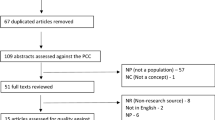

Methods

Data for messages sent and received for PGY 1–5 general surgery residents from April to December 2021 were obtained. A multi-professional group was created, and nursing-led education was delivered to surgical nurses from July to September 2021. Baseline messaging data from April to June 2021 were compared to post-education data obtained from October to December 2021. A two-sample t test was performed with a statistical significance at p ≤ .05. Surgical residents were surveyed for messaging burden, and data were compared between baseline and post-education.

Results

Comparing baseline to post-education messaging data, PGY 1 surgical residents received an average of seven fewer messages per day (22 vs 15, p = .019). Similarly, PGY 1–3 surgical residents received an average of six fewer messages per day (18 vs 13, p = .007). Survey data showed a similar burden perceived between baseline survey in July 2021 (25 residents) and post-education survey in March 2022 (9 residents).

Conclusion

Targeted multi-professional education decreases the volume of messages received by surgical residents, but not a reduction in a subjective burden. Additional solutions are required to realize a meaningful improvement in use from MMDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lebares CC, et al. Burnout and stress among US surgery residents: psychological distress and resilience. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(1):80–90.

Ellis RJ, et al. Comprehensive characterization of the general surgery residency learning environment and the association with resident burnout. Ann Surg. 2021;274(1):6–11.

Kairys JC, et al. Changes in operative case experience for general surgery residents: has the 80-hour work week decreased residents’ operative experience? Adv Surg. 2009;43:73–90.

Elhage SA, et al. Distractions during patient handoff: the application-based messaging volume on general surgery interns. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(6):e201–8.

Aziz S, et al. Resident and nurse perspectives on the use of secure text messaging systems. J Hosp Med. 2022;17(11):880–7.

Hilliard RW, Haskell J, Gardner RL. Are specific elements of electronic health record use associated with clinician burnout more than others? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(9):1401–10.

Martín-Brufau R, et al. Emotion regulation strategies, workload conditions, and burnout in healthcare residents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21).

Plant MA, Fish JS. Resident use of the Internet, e-mail, and personal electronics in the care of surgical patients. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):215–23.

Khanna RR, Wachter RM, Blum M. Reimagining electronic clinical communication in the post-pager, smartphone era. JAMA. 2016;315(1):21–2.

Flynn EA, et al. Impact of interruptions and distractions on dispensing errors in an ambulatory care pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(13):1319–25.

Wiegmann DA, et al. Disruptions in surgical flow and their relationship to surgical errors: an exploratory investigation. Surgery. 2007;142(5):658–65.

Katz MH, Schroeder SA. The sounds of the hospital. Paging patterns in three teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(24):1585–1589.

Fargen KM, et al. An observational study of hospital paging practices and workflow interruption among on-call junior neurological surgery residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):467–71.

Harvey R, Jarrett PG, Peltekian KM. Patterns of paging medical interns during night calls at two teaching hospitals. CMAJ. 1994;151(3):307–11.

Witherspoon L, et al. Is it time to rethink how we page physicians? Understanding paging patterns in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):992.

The Joint Commission Most Commonly Reviewed Sentinel Event Types.

Smith AD, et al. Text paging of surgery residents: efficacy, work intensity, and quality improvement. Surgery. 2016;159(3):930–7.

Espino S, Cox D, Kaplan B. Alphanumeric paging: a potential source of problems in patient care and communication. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(6):447–51.

Segall N, et al. Can we make postoperative patient handovers safer? A systematic review of the literature. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(1):102–15.

Agarwal HS, et al. Standardized postoperative handover process improves outcomes in the intensive care unit: a model for operational sustainability and improved team performance. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(7):2109–15.

Mukhopadhyay D, et al. Implementation of a standardized handoff protocol for post-operative admissions to the surgical intensive care unit. Am J Surg. 2018;215(1):28–36.

Labrague LJ, de Los Santos JAA. Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(3):395–403.

Wright DR. Texting of patient information among healthcare providers. Center for clinical standards and quality/survey & certification group, December 28, 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ricker, A.B., Shastry, V., Rossi, I. et al. Multi-professional education reduces surgical resident messaging volume. Global Surg Educ 3, 59 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-024-00253-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-024-00253-6