Abstract

Objectives

Acute atrial fibrillation (AF)/flutter (AFL) is a common emergency department (ED) presentation. In 2021, an updated version of CAEP’s Acute AF/AFL Best Practices Checklist was published, seeking to guide management. We assessed the alignment with and safety of application of the Checklist, regarding stroke prevention and disposition.

Methods

This health records review included adults presenting to two tertiary care academic EDs between January and August 2022 with a diagnosis of acute AF/AFL. Patients were excluded if their initial heart rate was < 100 or if they were hospitalized. Data extracted included: demographics, CHADS-65 score, clinical characteristics, ED treatment and disposition, and outpatient prescriptions and referrals. Our primary outcome was the proportion of patient encounters with one or more identified safety issues. Each case was assessed according to seven predetermined criteria from elements of the CAEP Checklist and either deemed “safe” or to contain one or more safety issues. We used descriptive statistics with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

358 patients met inclusion criteria. The mean age was 66.9 years, 59.2% were male and 77.4% patients had at least one of the CHADS-65 criteria. 169 (47.2%) were not already on anticoagulation and 99 (27.6%) were discharged home with a new prescription for anticoagulation. The primary outcome was identified in 6.4% (95% CI 4.3–9.5) of encounters, representing 28 safety issues in 23 individuals. The safety concerns included: failure to prescribe anticoagulation when indicated (n = 6), inappropriate dosing of a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) (n = 2), inappropriate prescription of rate or rhythm control medication (n = 9), and failure to recommend appropriately timed follow-up for new rate control medication (n = 11).

Conclusions

There was a very high level of ED physician alignment with CAEP’s Best Practices Checklist regarding disposition and stroke prevention. There are opportunities to further improve care with respect to recommendation of anticoagulation and reducing inappropriate prescriptions of rate or rhythm medications.

Résumé

Objectifs

La fibrillation auriculaire aiguë (FA)/flutter (FAT) est une présentation courante aux urgences (SU). En 2021, une version mise à jour de la liste de vérification des pratiques exemplaires en matière de FA/FAT aiguë du CAEP a été publiée, dans le but de guider la direction. Nous avons évalué l’harmonisation et la sécurité de l’application de la liste de contrôle en ce qui concerne la prévention et la disposition des AVC.

Méthodes

Cet examen des dossiers de santé comprenait des adultes qui se sont présentés à deux urgences universitaires de soins tertiaires entre janvier et août 2022 avec un diagnostic d’AF/AFL aigu. Les patients étaient exclus si leur fréquence cardiaque initiale était inférieure à 100 ou s’ils étaient hospitalisés. Les données extraites comprenaient les données démographiques, le score CHADS-65, les caractéristiques cliniques, le traitement et la disposition des urgences, ainsi que les prescriptions et les références ambulatoires. Notre résultat principal était la proportion de patients qui rencontraient un ou plusieurs problèmes de sécurité identifiés. Chaque cas a été évalué selon sept critères prédéterminés à partir des éléments de la liste de vérification du PPVE et jugé « sécuritaire » ou comportant un ou plusieurs problèmes de sécurité. Nous avons utilisé des statistiques descriptives avec des intervalles de confiance de 95 %.

Résultats

358 patients répondaient aux critères d’inclusion. L’âge moyen était de 66.9 ans, 59.2% étaient des hommes et 77.4% des patients avaient au moins un des critères CHADS-65. 169 (47.2%) n’étaient pas déjà sous anticoagulation et 99 (27.6%) ont été renvoyés à la maison avec une nouvelle prescription d’anticoagulation. Le critère de jugement principal a été identifié dans 6.4 % (IC à 95 % 4.3–9.5) des rencontres, ce qui représente 28 problèmes d’innocuité chez 23 personnes. Parmi les préoccupations en matière d’innocuité, mentionnons l’omission de prescrire un anticoagulant lorsque cela est indiqué (n = 6), l’administration inappropriée d’un anticoagulant oral direct (n = 2), la prescription inappropriée d’un médicament pour contrôler le rythme ou le rythme (n = 9), et l’omission de recommander un suivi bien chronométré vers le haut pour le nouveau médicament de contrôle de taux (n = 11).

Conclusions

Il y avait un très haut niveau d’harmonisation des médecins de l’urgence avec la liste de vérification des pratiques exemplaires de l’ACMU en ce qui concerne la disposition et la prévention des accidents vasculaires cérébraux. Il est possible d’améliorer davantage les soins en ce qui concerne la recommandation d’anticoagulation et de réduire les prescriptions inappropriées de médicaments à taux ou à rythme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What is known about the topic? |

CAEP’s Best Practices Checklist for acute atrial fibrillation/flutter provides a framework for decisions around anticoagulation and disposition/follow-up. |

What did this study ask? |

How aligned are ED physicians with the anticoagulation and follow-up portions of the checklist? |

What did this study find? |

This study found that 6.4% of patients had one or more safety issues relating to stroke prevention and follow-up. |

Why does this study matter to clinicians? |

Identifying areas of discrepancy can guide the development of interventions to improve safety for patients presenting with atrial fibrillation/flutter. |

Introduction

Acute atrial fibrillation (AF)/flutter (AFL) is a common emergency department (ED) presentation, with ED practices varying between countries, hospitals and individual providers [1, 2]. In 2021, an updated version of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians’ (CAEP) Acute AF/AFL Best Practices Checklist was published, seeking to improve ED management of these conditions [3].

Most patients in Canada who present with acute AF/AFL are managed in the ED and then discharged home, with recent studies showing a discharge rate of over 90% [4]. With many patients receiving a new diagnosis of acute AF/AFL, and some also having limited contact with the medical system, this is a critical moment for both stroke prevention and appropriate follow-up recommendations. While the CAEP Checklist provides recommendations on both topics, it is unclear what the actual physician alignment is with these recommendations and whether deviation from the checklist leads to any change in safety outcomes for patients.

Previous studies have explored reasoning for lack of compliance with stroke prevention guidelines and found an array of patient-related and physician-related factors that may have an impact [5]. With a goal of improving safety for patients presenting with acute AF/AFL to EDs, an assessment of current alignment with guidelines is necessary to identify gaps in care. Thus, our objective was to assess the alignment with and safety of application of the CAEP checklist as it pertains to stroke prevention, disposition, and follow-up recommendations. A complementary paper evaluated alignment with the first two parts of the checklist: initial assessment and rhythm and rate control [6].

Methods

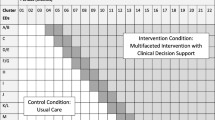

Study design and setting

This was a health records review of all patients presenting to the ED with acute AF/AFL who were treated by an emergency physician and discharged home.

Study setting

Our study setting was two tertiary care academic EDs between January and August 2022. There are a total of 180,000 patient visits to these sites annually. Patients are managed by one of the 95 attending physicians and 55 emergency medicine resident physicians/fellows.

Participants

We included all adults 18 years or older who presented to the ED with acute AF/AFL, who were treated by the ED physician and were discharged home. Acute AF/AFL was defined as in the checklist as being cases of recent-onset AF/AFL with an onset generally less than 48 h but possibly up to seven days [3]. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: initial ECG-recorded heart rate less than 100 beats per minute, patient transferred from another center or directly to an admitted service, patient admitted to hospital or deceased, patient presentation not related to AF/AFL, or if they were ultimately not found to have acute AF/AFL. Our study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Outcome measures

Our primary outcome was the proportion of patient encounters with one or more identified safety issues pertaining to the “Stroke Prevention” and the “Disposition and Follow-up” sections of the CAEP Checklist. Seven potential safety issues were identified and predetermined by a research team that included resident and attending ED physicians as well as members of the team that formulated the CAEP Checklist. The issues were categorized as either moderate or severe safety concerns. The identified severe issues are as follows: 1. Failure to prescribe anticoagulation when indicated, 2. Prescription of anticoagulation if contraindicated, 3. Prescription of a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC) if contraindicated, 4. Inappropriate dosing of a DOAC. The potential moderate safety concerns were: 1. Inappropriate prescription of warfarin over a DOAC, 2. Inappropriate prescription of rate or rhythm control medication, 3. Failure to recommend follow-up within 1 week for new warfarin prescription or rate control medication. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of individuals who were recommended follow-up, the number and reason for return ED visits within 30 days, and the number of adverse events within 30 days.

Data collection

Patient records were screened via an ECG database. This database contains all ECGs recorded in the ED that are all over-read by a staff cardiologist. ECGs were extracted from the database if a mention of “atrial fibrillation” or “atrial flutter” was found in either the preliminary machine-generated diagnosis or the formal diagnosis made by the reviewing cardiologist. The patient record was then reviewed to ascertain inclusion and exclusion criteria. For included patients, data were collected on demographics, history and physical exam during ED visit, ED treatment, disposition decisions, outpatient prescriptions, referrals and 30-day outcomes.

Data analysis and sample size

Following initial data collection, each case was assessed according to the seven predetermined potential safety issues. Any disagreement between independent reviewers were discussed with all team members are resolved by consensus. Cases with identified safety issues were then reviewed to assess for a relationship between the presence of safety issues and the occurrence of adverse events. We estimated that at least 300 patient visits were required to adequately depict the incidence of adverse events. Analysis consisted of descriptive statistics with 95% confidence intervals (CI) appropriate for continuous, ordinal, and categorical outcomes.

Results

A total of 2242 ECGs were screened for inclusion and 358 patients met inclusion criteria (Appendix 1 Flow Diagram). Details of patient demographics and ED course can be found in Table 1. At discharge, one third of patients (33.5%) were prescribed a new medication, with 99 individuals (27.7%) receiving a new anticoagulant prescription and 54 patients (15.1%) starting a new rate or rhythm control agent. Most patients (71.2%) were recommended follow-up. Thirty days following discharge, 24% of included patients had one or more ED return visits. Acute AF/AFL was the reason for return in most (73.3%) cases. Adverse events within 30 days included one stroke, one major bleeding event, and one minor bleeding event. Given that data was obtained from clinician documentation, there were rare instances of missing data of low significance. For example, in 24/358 patients, the timing since onset of symptoms was not evident in the patient chart and was documented as “unknown”.

The primary outcome of safety concern was identified in 6.4% (95% CI 4.3–9.5) of encounters, representing 28 safety issues in 23 individuals. The severe safety issues identified were: failure to prescribe anticoagulation when indicated (n = 6) and inappropriate dosing of a DOAC (n = 2). Moderate issues identified included: inappropriate prescription of rate or rhythm control medication (n = 9) and failure to recommend appropriately timed follow-up for new warfarin or rate control medication (n = 11). All nine cases with inappropriate rate/rhythm control prescriptions were patients who had converted to sinus rhythm but were still prescribed a beta blocker or calcium channel blocker on discharge. Where a safety concern was identified; a patient prescribed a subtherapeutic dose of a DOAC subsequently suffered a stroke.

Discussion

Interpretation

There was overall very good alignment with the 2021 CAEP Acute AF/AFL Best Practices Checklist, with one or more safety issues being identified in 6.4% of cases. The most common safety issues were the omission of indicated anticoagulation, the inappropriate prescription of rate control agents, and a failure to ensure appropriate follow-up after prescribing these medications. We found that about a quarter of patients included in our study returned to the ED within 30 days, with AF/AFL being their most frequent reason for returning. Within 30 days of discharge, there were very few adverse events.

Previous studies

While no study to our knowledge has assessed ED physician alignment with the CAEP checklist, previous studies have supported the initiation of anticoagulation for stroke prevention directly in the ED. It is well established that when indicated, anticoagulation significantly decreases stroke risk [7]. Atzema et al. demonstrated a substantially higher oral anticoagulant use at six months post ED visit when this was prescribed during the ED visit as opposed to later by another provider [8]. The importance of prompt initiation of anticoagulation is emphasized in the checklist and in national guidelines [3, 9].

A complementary paper from our institution evaluated alignment with recommendations for initial assessment as well as rate and rhythm control, but did not assess stroke prevention and disposition [6].

Strengths and limitations

This is the first paper to evaluate ED physician alignment with the CAEP checklist for stroke prevention and disposition. A major strength of this study was the large number of included patients as we included all patients with acute AF/AFL over a prolonged period of eight months, allowing for a valuable assessment of current practices at the studied institutions. A limitation, given this study’s health records design, is our reliance on chart documentation, which may lead to overestimated misalignment with the checklist. For instance, shared decision-making discussions and informal follow-up recommendations may not always be detailed in a patient’s chart. Of the six patients who were not prescribed anticoagulation when indicated, one was recommended a DOAC; however, it was documented that the patient had refused. It is not possible to know if a similar situation occurred for other patients included in our study. Second, while the checklist is well-known at the study institutions via faculty-wide Grand Rounds and emails, access to a mobile app, and high visibility posters around the ED, it is not possible to know whether physicians were consistently using it or if their treatment decisions were based on their usual practice.

Clinical implications

Our study showed overall high physician alignment with the CAEP checklist at two ED sites. There remain important areas where safety can be further improved within the stroke prevention and follow-up portions of AF/AFL management. Specifically, efforts can be made to verify dosing for DOAC prescriptions and to avoid rate control medications in those who have converted to sinus rhythm. This can be accomplished by frequent familiarization with guidelines. We therefore encourage ED physicians to refer to the CAEP checklist or the free smartphone application (CAEP Atrial Fibrillation Guide on iOS/Android) [3].

Research implications

Our improved understanding of the areas where checklist deviation is most common can guide future research and initiatives to improve these aspects of care. Previous studies have shown that quality improvement initiatives utilizing algorithmic care pathways for patients presenting to EDs with acute AF/AFL can lead to better compliance with stroke prevention and follow-up guidelines [10]. Our study may prompt similar initiatives both locally and nationally to improve ED management of Acute AF/AFL.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrated very good overall alignment with CAEP’s Checklist regarding stroke prevention and disposition/follow-up. There remain opportunities to further improve care with respect to recommendation of anticoagulation and reducing inappropriate prescriptions of rate or rhythm control medications.

Data availability

Data available within the article or its supplementary materials.

References

Rogenstein C, Kelly AM, Mason S, Schneider S, Lang E, Clement CM, et al. An international view of how recent-onset atrial fibrillation is treated in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(11):1255–60.

Stiell IG, Clement CM, Brison RJ, Rowe BH, Borgundvaag B, Langhan T, et al. Variation in management of recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter among academic hospital emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(1):13–21.

Stiell IG, de Wit K, Scheuermeyer FX, Vadeboncoeur A, Angaran P, Eagles D, et al. 2021 CAEP acute atrial fibrillation/flutter best practices checklist. Can J Emerg Med. 2021;23(5):604–10.

Stiell IG, Sivilotti MLA, Taljaard M, Birnie D, Vadeboncoeur A, Hohl CM, et al. Electrical versus pharmacological cardioversion for emergency department patients with acute atrial fibrillation (RAFF2): a partial factorial randomised trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10221):339–49.

Gebreyohannes EA, Salter S, Chalmers L, Bereznicki L, Lee K. Non-adherence to thromboprophylaxis guidelines in atrial fibrillation: a narrative review of the extent of and factors in guideline non-adherence. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2021;21(4):419–33.

Mattice AMS, Adler S, Eagles D, Yadav K, Hui S, Azward A, Pandey N, Stiell IG. Assessment of physician compliance to the CAEP 2021 Atrial Fibrillation Best Practices Checklist for rate and rhythm control in the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-024-00669-5

Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):857–67.

Atzema CL, Jackevicius CA, Chong A, Dorian P, Ivers NM, Parkash R, et al. Prescribing of oral anticoagulants in the emergency department and subsequent long-term use by older adults with atrial fibrillation. CMAJ. 2019;191(49):E1345–54.

Andrade JG, Aguilar M, Atzema C, Bell A, Cairns JA, Cheung CC, et al. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(12):1847–948.

Masica A, Brown R, Farzad A, Garrett JS, Wheelan K, Nguyen HL, et al. Effectiveness of an algorithm-based care pathway for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation presenting to the emergency department. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2022;3(1): e12608.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Adler, S., Mattice, A.M.S., Eagles, D. et al. How well do ED physician practices align with the CAEP acute atrial fibrillation checklist for stroke prevention and disposition?. Can J Emerg Med 26, 327–332 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-024-00676-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-024-00676-6