Abstract

Objectives

To determine the association between neighborhood marginalization and rates of pediatric ED visits in Ottawa, Ontario. Secondary objectives investigated if the association between neighborhood marginalization and rates varied by year, acuity, and distance to hospital.

Methods

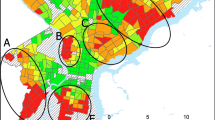

We calculated rates of pediatric ED visits per 1000 person-years for census dissemination areas within 100 km of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario for patients < 18 years old from January 2018 through December 2020. The 2016 Ontario Marginalization Index categorized neighborhoods along quintiles of residential instability, material deprivation, ethnic concentration, and dependency. Generalized mixed-effects models determined the incidence rate ratios of pediatric ED visits for each quintile of marginalization; multivariate models were used to control for year of presentation and distance to hospital. Analysis was repeated for low versus high acuity ED visits.

Results

There were 154,146 ED visits from patients in 2055 census dissemination areas within 100 km of CHEO from 2018 to 2020. After controlling for year and distance from hospital in multivariate analyses, there were higher rates of pediatric ED visits for dissemination areas with high residential instability, high material deprivation, and low ethnic concentration. These findings did not change according to visit acuity.

Conclusions

Neighborhood residential instability and material deprivation should be considered when locating alternatives to emergency care.

Résumé

Objectifs

Déterminer l’association entre la marginalisation du quartier et les taux de visites aux urgences pédiatriques à Ottawa, en Ontario. Les objectifs secondaires visaient à déterminer si l’association entre la marginalisation du quartier et les taux variait selon l’année, l’acuité et la distance à l’hôpital.

Méthodes

Nous avons calculé les taux de visites aux urgences pédiatriques par tranche de 1000 années-personnes dans les aires de diffusion du recensement à moins de 100 km du Centre hospitalier pour enfants de l’est de l’Ontario pour les patients de moins de 18 ans de janvier 2018 à décembre 2020. L’Indice de marginalisation de l’Ontario de 2016 classait les quartiers selon des quintiles d’instabilité résidentielle, de privation matérielle, de concentration ethnique et de dépendance. Les modèles à effets mixtes généralisés ont déterminé les ratios des taux d’incidence des visites aux urgences pédiatriques pour chaque quintile de marginalisation; des modèles multivariés ont été utilisés pour contrôler l’année de présentation et la distance à l’hôpital. L’analyse a été répétée pour les visites à l’urgence de faible acuité par rapport à haute acuité.

Résultats

Il y a eu 154 146 visites aux urgences de patients dans 2 055 aires de diffusion du recensement à moins de 100 km du CHEO de 2018 à 2020. Après avoir tenu compte de l’année et de la distance par rapport à l’hôpital dans les analyses multivariées, on a constaté des taux plus élevés de visites aux urgences pédiatriques dans les zones de diffusion présentant une instabilité résidentielle élevée, une privation matérielle élevée et une faible concentration ethnique. Ces résultats n’ont pas changé selon l’acuité de la visite.

Conclusions

L’instabilité résidentielle du quartier et la privation matérielle doivent être prises en compte lors de la recherche de solutions de rechange aux soins d’urgence.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information. NACRS emergency department visits and lengths of stay. 2022. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/nacrs-emergency-department-visits-and-lengths-of-stay.

To T, Terebessy E, Zhu J, Fong I, Liang J, Zhang K, et al. Did emergency department visits in infants and young children increase in the last decade? An Ontario Canada study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38(4):E1173–8.

Doan Q, Wong H, Meckler G, Johnson D, Stang A, Dixon A, et al. The impact of pediatric emergency department crowding on patient and health care system outcomes: a multicentre cohort study. CMAJ. 2019;191(23):E627–35.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Sources of potentially avoidable emergency department visits. 2014. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC2708.

World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. 2023. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

Rosychuk RJ, Chen A, McRae A, McLane P, Opsina MB, Stang A. Characteristics of pediatric frequent users of emergency departments in Alberta and Ontario. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38(3):108–14.

Seguin J, Osmanlliu E, Zhang X, Clavel V, Eisman H, Rodrigues R, et al. Frequent users of the pediatric emergency department. CJEM. 2018;20(3):401–8.

Beck AF, Huang B, Chundur R, Kahn RS. Housing code violation density associated with emergency department and hospital use by children with asthma. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(11):1993–2002.

Sheriff F, Agarwal A, Thipse M, Radhakrishnan D. Hot spots for pediatric asthma emergency department visits in Ottawa, Canada. J Asthma. 2022;59(5):880–9.

Portillo EN, Stack AM, Monuteaux MC, Curt A, Perron C, et al. Association of limited English proficiency and increased pediatric emergency department revisits. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(9):1001–11.

McDonald EJ, Quick M, Oremus M. Examining the association between community-level marginalization and emergency room wait time in Ontario. Canada Healthc Policy. 2020;15(4):64–76.

Statistics Canada. Illustrated glossary: Dissemination area. 2017. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/92-195-x/2016001/geo/da-ad/da-ad-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. Data tables, 2016 Census. 2019. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=109525&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2016&THEME=115&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=.

QGIS. A free and open source Geographic Information System. 2023. [cited 16 Jun 2023]. Available from: https://www.qgis.org/en/site/.

Statistics Canada. 2016 Census – Boundary files. 2019. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/geo/bound-limit/bound-limit-2016-eng.cfm.

Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion. Public Health Ontario. 2023. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/health-equity/ontario-marginalization-index.

van Ingen T, Matheson FI. The 2011 and 2016 iterations of the Ontario Marginalization Index: updates, consistency and a cross-sectional study of health outcome associations. Can J Public Health. 2022;113(2):260–71.

Zygmunt A, Tanuseputro P, James P, Lima I, Tuna M, Kendall CE. Neighbourhood-level marginalization and avoidable mortality in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study. Can J Public Health. 2020;111(2):169–81.

Bozdogan H. Model selection and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC): the general theory and its analytic extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52:345–70.

Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychol Bull. 1995;118(3):392–404.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2021. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/.

Rink N, Muttalib F, Morantz G, Chase L, Cleveland J, Rousseau C, et al. The gap between coverage and care-what can Canadian paediatricians do about access to health services for refugee claimant children? Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22(8):430–7.

Rousseau C, Laurin-Lamothe A, AnnekeRummens J, Meloni F, Steinmetz N, Alvarez F. Uninsured immigrant and refugee children presenting to Canadian paediatric emergency departments: disparities in help-seeking and service delivery. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(9):465–9.

Khan AM, Urquia M, Kornas K, Henry D, Cheng SY, Bornbaum C, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in all-cause, premature and avoidable mortality among immigrants and long-term residents using linked death records in Ontario, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(7):625–32.

Nestel S. Colour coded health care: The impact of race and racism on Canadians’ health. Wellesley Institute. 2012. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Colour-Coded-Health-Care-Sheryl-Nestel.pdf.

Glauser W. Why aren’t the doctors where the sick people are? The Local. 2019. [cited 2023 Jun 16]. Available from: https://thelocal.to/why-arent-the-doctors-where-the-sick-people-are/.

Ohle R, Ohle M, Perry JJ. Factors associated with choosing the emergency department as the primary access point to health care: a Canadian population cross-sectional study. CJEM. 2017;19(4):271–6.

Andermann A. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016;188(17–18):E474–83.

Tedford NJ, Keating EM, Ou Z, Holsti M, Wallace AS, Robison JA. Social needs screening during pediatric emergency department visits: disparities in unmet social needs. Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(8):1318–27.

Wallace AS, Luther BL, Guo J-W, Wang C-Y, Sisler SM, Wong B. Implementing a social determinants screening and referral infrastructure during routine emergency department visits, Utah, 2017–2018. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E45.

Wallace AS, Luther BL, Sisler SM, Wong B, Guo J-W. Integrating social determinants of health screening and referral during routine emergency department care: evaluation of reach and implementation challenges. Implement Sci Commun. 2021;2(1):114.

Hartford EA, Thomas AA, Kerwin O, Usoro E, Yoshida H, Burns B, et al. Toward improving patient equity in a pediatric emergency department: a framework for implementation. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;81(4):385–92.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

AlSaeed, H., Sucha, E., Bhatt, M. et al. Rates of pediatric emergency department visits vary according to neighborhood marginalization in Ottawa, Canada. Can J Emerg Med 26, 119–127 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-023-00625-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-023-00625-9

Keywords

- Social marginalization

- Pediatric emergency medicine

- Health services accessibility

- Neighborhood characteristics