Abstract

Objective

Due to the COVID pandemic, restrictions were put in place mandating that all residency interviews be transitioned to a virtual format. Canadian CCFP(EM) programs were among the first to embark on this universal virtual interview process for resident selection. Although there have been several recent publications suggesting best practice guidelines for virtual interviews in trainee selection, pragmatic experiences and opinions from Program Directors (PDs) are lacking. This study aimed to elicit the experiences and perspectives of CCFP(EM) PDs after being amongst the first to conduct universal virtual interviews in Canada.

Methods

A 17-item online survey was created and distributed to all CCFP(EM) PDs (n = 17). It explored the virtual interview format employed, perceived advantages and disadvantages of a virtual configuration, confidence in determining a candidate’s rank order, and PD preference for employing a virtual interview format in the future. It also elicited practical advice to conduct a smooth and successful virtual interview day.

Results

The survey response rate was 76.5% (13/17). Nine respondents (69.2%) agreed that the virtual interview format enabled them to confidently determine a candidate’s rank order. With respect to preference for future use of virtual interviews, 23.1% agreed, 38.5% disagreed and 38.5% neither agreed nor disagreed. Inductive thematic analysis of free text responses revealed themes related to virtual interview advantages (time, financial, and resource costs), disadvantages (difficulty promoting smaller programs, getting a ‘feel’ for candidates and assessing their interpersonal skills), and practical tips to facilitate virtual interview processes.

Conclusion

Once restrictions are lifted, cost-saving advantages must be weighed against suggested disadvantages such as showcasing program strengths and assessing interpersonal skills in choosing between traditional and virtual formats. Should virtual interviews become a routine part of resident selection, the advice suggested in this study may be considered to help optimize a successful virtual interview process.

Résumé

Objectif

En raison de la pandémie de COVID-19, des restrictions ont été mises en place pour obliger toutes les entrevues de résidence à passer à un format virtuel. Les programmes canadiens CCMF(MU) ont été parmi les premiers à se lancer dans ce processus universel d'entrevue virtuelle pour la sélection des résidents. Bien qu’il y ait eu plusieurs publications récentes suggérant des lignes directrices de pratiques exemplaires pour les entrevues virtuelles dans la sélection des stagiaires, les expériences et les opinions pragmatiques des directeurs de programme (DP) font défaut. Cette étude visait à recueillir les expériences et les points de vue des DP du CCMF(MU) après avoir été parmi les premiers à mener des entrevues virtuelles universelles au Canada.

Méthodes

Une enquête en ligne de 17 questions a été créée et distribuée à tous les DP du CCMF(MU) (n=17). Elle a exploré le format d'entretien virtuel employé, les avantages et inconvénients perçus d'une configuration virtuelle, la confiance dans la détermination de l'ordre de classement d'un candidat, et la préférence des DP pour l'emploi d'un format d'entretien virtuel à l'avenir. Elle a également permis de recueillir des conseils pratiques pour mener à bien une journée d'entretiens virtuels.

Résultats

Le taux de réponse à l'enquête a été de 76,5 % (13/17). Neuf répondants (69,2 %) ont convenu que le format d'entretien virtuel leur a permis de déterminer avec confiance l'ordre de classement d'un candidat. En ce qui concerne la préférence pour l’utilisation future des entrevues virtuelles, 23,1 % étaient d’accord, 38,5 % étaient en désaccord et 38,5 % n’étaient ni d’accord ni en désaccord. L'analyse thématique inductive des réponses en texte libre a révélé des thèmes liés aux avantages des entretiens virtuels (coûts en temps, en argent et en ressources), aux inconvénients (difficulté à promouvoir les petits programmes, à se faire une idée des candidats et à évaluer leurs compétences interpersonnelles) et aux conseils pratiques pour faciliter les processus d'entretien virtuel.

Conclusion

Une fois les restrictions levées, les avantages liés à la réduction des coûts doivent être mis en balance avec les inconvénients suggérés, tels que la mise en valeur des points forts du programme et l'évaluation des compétences interpersonnelles, lors du choix entre les formats traditionnels et virtuels. Si les entretiens virtuels devaient devenir un élément de routine dans la sélection des résidents, les conseils suggérés dans cette étude pourraient être pris en compte pour aider à optimiser un processus d'entretien virtuel réussi.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is known about the topic? |

Perspectives, experiences, and advice from Canadian Program Directors (PDs) about conducting virtual resident interviews are lacking. |

What did this study ask? |

What were the experiences and perspectives of CCFP(EM) PDs after being amongst the first to conduct universal virtual interviews in Canada? |

What did this study find? |

Promoting smaller programs and judging interpersonal skills through virtual interviews present challenges. Experience-guided advice is also suggested. |

Why does this study matter to clinicians? |

Advantages and disadvantages must be considered in choosing between formats. Virtual interviews may be informed by experience-guided advice suggested. |

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created several challenges for medical education including recruitment and selection of trainees. Traditionally, residency programs in Canada have conducted in-person interviews to aid in candidate selection. In May 2020, it was mandated that all program interviews be transitioned to virtual format [1]. Advantages to virtual interviews include improved convenience and flexibility and reduced financial and resource costs [2,3,4,5]. Posited disadvantages include potential technological difficulties, lack of personal interactions which may be useful for gleaning information about candidates’ interpersonal skills and professionalism, and a loss of opportunity for applicants to observe the facilities and culture of a program directly [3, 4].

In November 2020, family medicine/emergency medicine enhanced skills (CCFP(EM)) programs across Canada were among the first to embark on this universal virtual interview process for resident selection. There are many “best-practices” for conducting interviews which include utilizing structured, standardized, and blinded interview processes [6]. PDs place great weight on interviews during trainee selection [7]. In 2013, a working group produced a report of Best Practices in Application and Selection which included recommendations pertaining to candidate interviews [8]. This report emphasized the need for standardized and objective interview processes but did not suggest a need for interviews to occur-in person. Although there have been several recent publications suggesting theoretical best practice guidelines for virtual residency interviews [2,3,4], pragmatic experiences and opinions from Program Directors (PDs) on conducting such interviews are lacking.

The purpose of this study was to elicit the experiences and perspectives of CCFP(EM) PDs and propose experience-guided advice regarding virtual interview processes. Results of this study may assist both undergraduate and post-graduate training programs to implement and conduct future virtual interviews.

Methods

Design

This was a single cohort survey of CCFP(EM) PDs. This study received ethics exemption from the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board.

Participants and recruitment

All 17 CCFP(EM) Program Directors received an email invitation in February 2021 to voluntarily participate in this anonymous survey. They were selected as they were amongst the first to conduct universal virtual interviews for resident selection in Canada and therefore be able to offer first-hand insights and experience.

Survey content and design

Survey methodology was chosen for the convenience and timeliness of survey distribution, cost effectiveness of data collection, and ease of respondent participation. The designed survey questions allowed the study team to gather data about the format and structure of virtual interviews used by each participant and how these differed from traditional in-person interviews, as well as the perceived challenges and advantages of conducting virtual interviews.

A 17-item electronic survey was created based on a review of existing literature of postulated best practices for virtual interviews and overall resident selection (Appendix 1). Recent virtual interview experiences of research team members were also considered in the development of the survey.

The survey was piloted with local enhanced skills PDs to solicit feedback regarding question clarity and readability.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics by calculating frequencies and percentages. Due to the small sample size, analysis of Likert-Scale responses was conducted by agreement rather than strength of the agreement. Positive indicators (strongly agree and agree) and negative indicators (strongly disagree and disagree) were collapsed. Inductive thematic analysis of qualitative data was conducted following the approach described by Braun and Clark [9]. Free text responses were reviewed by two study team members (JL and AN) and coded line-by-line. Codes were then collated and synthesized to identify themes. Of note, two authors (AN and JL) are CCFP(EM) PDs and the third author WJC) is highly involved in an FRCPC EM residency program.

Results

The survey was completed by 13 CCFP(EM) PDs (response rate of 76.5%).

Most interview members connected to the platforms individually from different locations (69.2%), citing local COVID restrictions as the reason for this format. Four (33.3%) programs conducted more interviews than in previous years. Two (15.4%) programs modified their traditional interview format by adding clinical knowledge stations to better discriminate between candidates as these could not be directly assessed due to cancellation of visiting electives.

Most respondents indicated that their interview day ran smoothly with minimal technological interruptions (92.3%). One respondent (7.7%) indicated that interviewees experienced internet connectivity issues, while two programs (15.4%) reported internet problems for interviewers.

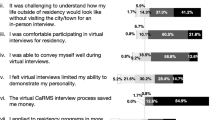

Nine respondents (69.2%) agreed that the virtual interview format enabled them to confidently determine a candidate’s rank order. With respect to preference for future virtual interviews, responses were mixed. Three respondents agreed (23.1%), five respondents disagreed (38.5%) and five respondents neither agreed nor disagreed (38.5%).

Inductive thematic analysis of free text responses revealed several themes and are summarized in Appendix 2. Themes included: (1) advantages and disadvantages to conducting virtual interviews; (2) technological considerations; and (3) experience-based advice to facilitate the virtual interview process. Experience-based advice elicited can be found in Table 1.

Advantages to virtual interviews included convenience, decreased costs, and improved time management on the actual interview day. Disadvantages included difficulty promoting smaller and more remote programs, difficulty getting a “feel” for candidates in an artificial environment, potential for technological disruptions, and more work to organize. One respondent stated, “…there is something profoundly lost when interviewing virtually. The nonverbal nuances are not there to make meaningful connections”. With respect to the challenge of showcasing programs and facilities, one respondent wrote, “it’s the people that make smaller programs worth coming to. If you can’t make those connections in person, applicants aren’t going to rank your program highly”.

Discussion

Interpretation and previous studies

This is the first Canadian study looking at the experiences of PDs in conducting mandatory virtual interviews for post-graduate trainee selection in a CaRMS match.

The advantages to a virtual interview format reported in this survey included improved time management on interview day and convenience for both interviewers and candidates. Numerous respondents commented on financial, temporal, and environmental cost savings associated with conducting interviews virtually. Both of these findings are supported in the literature [5, 10]. One recent study of Canadian general surgery applicants found that the mean travel costs for in-person interviews was $4866 and 1.82 tonnes of CO2 emissions per applicant [5].

The disadvantages of virtual interviews reported in our survey are also consistent with the literature. Some respondents indicated that they found virtual interviews to be cold and artificial. Another theme expressed by participants was the loss of meaningful personal connection and the inability to get a good “read” or “feel” for candidates [3]. This concept is supported by a recent study where PDs indicated that they found it more difficult to establish rapport with candidates in a virtual interview format [11]. Losing this personal interaction could detract from gaining important insights into important interpersonal skills and professional behaviour of candidates [4].

Our survey respondents made numerous comments about the challenges of showcasing programs and facilities through a virtual interview format, especially for smaller and more remote programs. This aligns with previous literature which has reported concerns of applicants not getting a “feel” for a site [11] as well as difficulty showcasing the camaraderie amongst trainees and faculty, factors shown to be highly valued by EM applicants [3, 12, 13]. In one recent survey of CCFP(EM) applicants, collegiality between faculty and residents was reported as being highly influential in first-choice program selection [14]. Novel recruitment strategies such as video-tours and promotional videos have been recommended to navigate these challenges [2], but it is unclear if these are as effective as in-person interactions.

In our study, most respondents indicated that they were able to confidently determine a candidate’s rank order. One study comparing a web-based to traditional in-person interview process found that faculty members felt less comfortable ranking candidates who were interviewed using a web-based platform compared to those interviewed in-person [10]. It is unclear if the lower confidence and comfort in determining rank-order by PDs is due to inherent differences in interview formats or related to an uneasiness with a novel process. Perhaps more experience with virtual processes will bolster confidence in ranking candidates. This is an area that would benefit from further exploration.

Implications

Survey respondents offered a lot of advice for conducting virtual interviews based on their recent experiences which is summarized in Table 1.

With respect to the use of future virtual interviews, responses in this survey were heterogeneous. Only three (23.1%) respondents indicated that they would prefer virtual interviews even if in-person interviews were permitted. This is less than reported in another study which found 55% of PDs agreed that future interviews should be held virtually, regardless of pandemic restrictions [15]. Some studies have suggested that virtual interviews should be considered as an adjunct instead of a replacement to traditional methods [10, 15]. This could lead to potential bias as the effect of in-person vs virtual interviews on candidate selection and rank order has not been fully elucidated. However, one small single-centre study suggested that interview type did not impact the likelihood of a prospective candidate being ranked or matched [16].

Strengths and limitations

While our survey had a strong response rate, the major limitations of this study are those inherent to any survey design including recall and response bias. Additionally, there was limited ability to explore participants’ responses in greater depth. Furthermore, this study surveyed PDs from a single subspeciality, which may limit the generalizability and transferability of results.

Future directions

Future directions include further exploration regarding differences in assessment of interpersonal skills through virtual interviews compared to traditional in-person methods, assessment of PD satisfaction of match results following use of a universal virtual interview process, and evaluation of advantages and disadvantages of a hybrid model of virtual and in-person interview methods.

Conclusions

Once restrictions mandating virtual interviews are lifted, advantages and disadvantages must be weighed in choosing an appropriate way forward. CCFP(EM) PDs are divided on their preference in conducting future virtual interviews. Advice suggested in this study may be considered by future interviewers to facilitate a successful virtual interview process.

References

The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada. Virtual interviews for the 2021 Medicine Subspecialty Match, Pediatric Subspecialty Match and Family Medicine, Enhanced Skills Match 2020 [Available from: www.afmc.ca/web/en/media-releases/may-26-2020.

Bernstein SA, Gu A, Chretien KC, Gold JA. Graduate Medical education virtual interviews and recruitment in the Era of COVID-19. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(5):557–60.

Sternberg K, Jordan J, Haas MRC, He S, Deiorio NM, Yarris LM, et al. Reimagining Residency Selection: Part 2-A Practical Guide to Interviewing in the Post-COVID-19 Era. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(5):545–9.

Davis MG, Haas MRC, Gottlieb M, House JB, Huang RD, Hopson LR. Zooming in versus flying out: virtual residency interviews in the Era of COVID-19. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4(4):443–6.

Fung B, Raiche I, Lamb T, Gawad N, MacNeill A, Moloo H. A chance for reform: the environmental impact of travel for general surgery residency interviews. Can Med Education Journal. 2019.

Huffcutt AI. From science to practice: seven principles for conducting employment interviews. Appl HRM Res. 2010;12(1):121.

Hale MKP, Frank JR, Cheung WJ. Resident selection for emergency medicine specialty training in Canada: A survey of existing practice with recommendations for programs, applicants, and references. CJEM. 2020;22(6):829–35.

Bandiera GW, Abrahams C., Cipolla A., Dosasni N., Edwards S., Fish J., et al. et al. Best practices in applications and selection - final report 2013 [Available from: https://pgme.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/BestPracticesApplicationsSelectionFinalReport-13_09_20.pdf.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Shah SK, Arora S, Skipper B, Kalishman S, Timm TC, Smith AY. Randomized evaluation of a web based interview process for urology resident selection. J Urol. 2012;187(4):1380–4.

D'Angelo JD, D'Angelo A-LD, Mathis KL, Dozois EJ, Kelley SR. Program director opinions of virtual interviews: whatever makes my partners happy. Journal of Surgical Education. 2021.

Yarris LM, Deiorio NM, Lowe RA. Factors applicants value when selecting an emergency medicine residency. Western J Emerg Med. 2009;10(3):159–62.

DeSantis M, Marco CA. Emergency medicine residency selection: factors influencing candidate decisions. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(6):559–61.

Leppard J, Nath A, Cheung WJ. Resident recruitment in the COVID-19 era: factors influencing program ranking by residents applying to a family medicine-emergency medicine training program. CJEM. 2021:1–5.

McKinley SK, Fong ZV, Udelsman B, Rickert CG. Successful virtual interviews: perspectives from recent surgical fellowship applicants and advice for both applicants and programs. Ann Surg. 2020;272(3):e192–6.

Arthur ME, Aggarwal N, Lewis S, Odo N. Rank and Match Outcomes of In-person and Virtual Anesthesiology Residency Interviews. J Educ Perioper Med. 2021;23(3):E664-E.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL and AN conceived the idea. JL collected and analyzed the data. JL drafted the manuscript. JL, AN, and WJC reviewed the manuscript and contributed substantially to its revision. J.L. takes responsibility for the study as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leppard, J., Nath, A. & Cheung, W.J. Experiences, perspectives, and advice for using virtual interviews in post-graduate trainee selection: a national survey of CCFP (EM) program directors. Can J Emerg Med 24, 498–502 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00312-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00312-1