Abstract

Purpose

Empathy and quality of educational environment appear to be inversely correlated with burnout but the relationship between the two is largely unknown. Our primary objective was to examine the relationship between postgraduate educational environment and empathy. Secondary objectives included impact of gender, residency year and on- versus off-service context on levels of empathy and educational environment.

Methods

A modified Dillman approach was used to conduct an email survey of Canadian Royal College Emergency Medicine residents in June 2020. The survey instrument included: demographic data, Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) and Scan of Postgraduate Educational Environment Domains (SPEED). Logistic and linear regressions evaluated the association between TEQ and SPEED, and mean SPEED scores and covariates, respectively.

Results

Response rate was 38% (138/363) with representation from all programs. Respondents were mean 30 years of age, 59% men and 25%, 20%, 18%, 24%, and 13% in postgraduate year (PGY) 1–5, respectively. There was no statistically significant association between high/low TEQ scores and mean SPEED score (p = 0.97). There were no statistically significant associations between any of the covariates and high/low TEQ scores (gender, p = 0.21; PGY, p = 0.58; on-versus off-service, p = 0.46) or mean SPEED score (gender, p = 0.95; PGY, p = 0.48; on- versus off-service, p = 0.07). Emergency medicine residents rated their educational environment on average 3.44 (+/- 0.43) out of four. 39 of 134 residents were found to have low empathy.

Conclusion

There was no association between empathy and educational environment. Further research is needed to elucidate modifiable factors contributing to the development of low empathy in emergency medicine residents.

Résumé

Objectif

L'empathie et la qualite de l'environnement educatif semblent etre inversement correlees a l'epuisement professionnel, mais la relation entre les deux est largement inconnue. Notre objectif principal etait d'examiner la relation entre l'environnement educatif de troisieme cycle et l'empathie. Les objectifs secondaires comprenaient l'impact du sexe, de l'annee de residence et du contexte en service ou hors service sur les niveaux d'empathie et l'environnement educatif.

Méthodes

Une approche Dillman modiiee a ete utilisee pour mener une enquete par courriel aupres des residents du College royal canadien de medecine d'urgence en juin 2020. L'instrument d'enquete comprenait : des donnees demographiques, le Toronto Empathy Questionnaire (TEQ) et le Scan of Postgraduate Educational Environment Domains (SPEED). Des regressions logistiques et lineaires ont evalue l'association entre TEQ et SPEED, et les scores SPEED moyens et les covariables, respectivement.

Résultats

Le taux de reponse etait de 38 % (138/363) avec une representation de tous les programmes. Les repondants etaient ages en moyenne de 30 ans, 59 % d'hommes et 25%, 20%, 18%, 24% et 13% de la 1re a la 5e annee de troisieme cycle, respectivement. Il n'y avait pas d'association statistiquement signiicative entre les scores TEQ eleves/bas et le score SPEED moyen (p = 0.97). Il n'y avait pas d'association statistiquement signiicative entre l'une des covariables et les scores TEQ eleves/faibles (sexe, p = 0,21 ; annee de troisieme cycle, p = 0.58 ; en service contre hors service, p = 0.46) ou le score SPEED moyen (sexe, p = 0.95 ; annee de troisieme cycle, p = 0.48 ; en service contre hors service, p = 0.07). Les residents en medecine d'urgence ont evalue leur environnement educatif a une moyenne de 3.44 ± 0.43. 4.39 des 134 residents se sont averes avoir une faible empathie.

Conclusion

Il n'y avait pas d'association entre l'empathie et l'environnement educatif. Des recherches supplementaires sont necessaires pour elucider les facteurs modiiables contribuant au developpement d'une faible empathie chez les residents en medecine d'urgence.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is known about the topic? |

Medical residents show a high level of burnout; empathy and educational environment appear to have an inverse relationship with burnout. |

What did this study ask? |

Does educational environment affect empathy in Canadian emergency medicine residents? |

What did this study find? |

Emergency medicine residents rate their educational environment well, 1/3 have low empathy and no association between environment and empathy was found. |

Why does this study matter to clinicians? |

The relationship between educational environment and empathy has been questioned. Other modifiable factors must be elucidated to combat resident burnout. |

Introduction

Burnout has a profound negative impact on healthcare providers including higher rates of suicide, substance abuse, medical errors and worse patient outcomes [1]. Health care providers have a higher degree of burnout and depression [2]. In fact, a meta-analysis of 114 studies by Naji et al., revealed that almost 1 in 2 medical residents meet criteria for burnout globally [2]. Some studies show that empathy (defined as the act of accurately perceiving another’s emotional state) is inversely correlated with burnout, and thus potentially a protective factor [3]. Empathy is also correlated with increased patient satisfaction, better patient adherence to treatment, adherence to follow up and clinical outcomes [4]. Unfortunately, empathy tends to decrease during clinical training years [5].

Empathy appears to be an important aspect of being a health care provider both for the provider themselves and patients. Educational environment is an important modifiable aspect of residency. The educational environment is typically assessed based on a learners experience of the emotional, physical and educational aspects of their environment [6]. Like empathy, a high quality educational environment has also been shown to be protective against burnout [7].

Despite empathy and educational environment being important aspects of residency, few studies have focused on residents and the impact of their educational environment on empathy. A better understanding could further elucidate factors contributing to burnout.

The primary objective of this study was to examine the association between residents’ perception of the quality of their postgraduate educational environment and their level of empathy. The educational environment was further broken down into three dimensions (atmosphere, content, and organization) to determine if any dimension has a stronger relationship with empathy. Secondary objectives included the impact of gender, postgraduate year (PGY) of residency and on- versus off-service on levels of empathy and quality of educational environment.

Methods

Study design & setting

A self-administered email survey was conducted between June 10–30th, 2020 using a modified Dillman approach. The Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board provided a waiver of ethics.

Study participants

The population surveyed were Canadian Royal College emergency medicine residents.

Survey content

We selected two measures of empathy and educational environment based on feasibility (length and ease of completion) and evidence of convergent validity of their respective constructs. Questionnaires were analyzed by study authors for relevancy to residency environment; no changes from the original questionnaires were made. Permission was obtained from each primary author for survey use.

Scan of postgraduate educational environment domains (SPEED)[6]

This is a 15-item questionnaire assessing the educational environment in three dimensions: content, atmosphere, and organization. It utilizes a 4-point Likert scale with higher numbers indicating increased agreement with the statement; the scores are averaged within the dimensions with a maximum score of 4.

Toronto empathy questionnaire (TEQ)[8]

This is a 16-item questionnaire with a 1-dimensional scale of empathy. It utilizes a 5-point Likert scale. The scoring is positively worded for questions: 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 13, and 16. It is negatively worded for: 2, 4, 7, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15. They are added to derive the total score. The result of this survey is dichotomous, a score below 45 indicating low empathy and a score of 45 and above indicating high empathy.

Demographic information collected included: university, gender, year of residency, name of current rotation, whether they had taken ≥ 5 days off for vacation in the last block, and how many main supervisors they have had during the block.

Survey administration

The surveys were translated into French by a bilingual colleague and was checked for clarity by a second bilingual colleague; respondents had the option of answering in either language. The surveys, along with an introduction letter, were uploaded onto SurveyMonkey.com. A unique collector URL was created for each emergency medicine program in Canada to help track responses.

The questionnaires were sent to all the emergency medicine program directors across Canada. All program directors were asked to distribute the surveys to their residents. Two reminder emails were sent at 1-week intervals. The chief residents of one program were contacted by the authors as the unique collector on SurveyMonkey.com showed no responses by week three of survey collection.

Statistical analysis

A logistic regression model was built to determine associations between measures of empathy (TEQ), educational environment (SPEED), and covariates (gender, age, PGY which have been previously shown to be correlated with empathy). Linear regression was used for associations between mean SPEED scores and covariates. Statistical analyses were completed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Response rate was 38.0% (138/363) with representation from all 14 Canadian Royal College Emergency Medicine programs and 24.6%, 20.3%, 18.1%, 23.9%, and 13.0% were in PGY 1–5, respectively. The respondents had a mean age of 29.8 (SD 3.2) years and n = 89 identified as male. Most respondents (n = 93) were on an emergency medicine rotation (i.e., on-service).

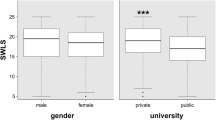

SPEED and TEQ scores are displayed in Fig. 1. There was no statistical association between composite SPEED scores and TEQ (p = 0.97; C-statistic = 0.51 (95% CI 0.40–0.62). When broken down by dimensions there was no statistically significant association between TEQ vs SPEED-Content (p = 0.71), TEQ vs SPEED-atmosphere (p = 0.47), TEQ vs SPEED-organization (p = 0.75). The c-statistic for TEQ and content, atmosphere and organization was 0.53 (95% CI 0.43–0.64).

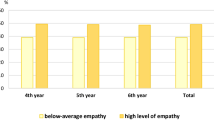

In PGY 1–4, low empathy was found in 26.5–33.3% of residents compared with residents in PGY 5 of whom 16.7% had low empathy. There was no statistically significant difference in empathy, as evaluated by the TEQ, and PGY (p = 0.58), gender (p = 0.20) or on/off service (p = 0.46). The c-statistic for TEQ and the covariates of: gender, year, service was 0.58 (95% CI 0.48–0.69).

Overall, residents rated their educational environment on average 3.44 (± 0.43) out of a maximum of 4. There was no statistically significant difference in rating based on gender (p = 0.95), PGY (p = 0.48) and on- versus off-service (p = 0.07). The r-square for SPEED and covariates of: gender, year and service was 0.027.

Discussion

This survey found no association between quality of educational environment and empathy in Canadian emergency medicine residents. There was no association between quality of educational environment or empathy and being on- or off-service, gender, or PGY. The quality of the postgraduate educational environment was rated well. Empathy was low in approximately 30% of residents surveyed.

Few studies have concretely explored a potential relationship between empathy and quality of educational environment. However, there is evidence supporting an inverse relationship between empathy and quality of educational environment with burnout in residents [3, 7]. Van Vendeloo et al. found among 1,231 Dutch residents a consistent negative relationship between SPEED score and burnout even after adjusting for various personal and work-related factors [7]. A survey of medical students by Roling et al. found that clinical environment (of which educational environment was one aspect) had a more significant impact on well-being than patient factors [9].

There is strong evidence of an association between empathy and burnout, although which variable affects the other is unclear [4]. Wilkinson et al. found an inverse relationship between empathy and burnout in their systematic review [3]. Previous studies have found that empathy is lower and burnout higher in medical students and residents in clinical training compared to non-medical controls [5]. Results found in this study demonstrate that approximately 1 in 3 emergency medicine residents have a low-level of empathy. It is difficult to compare the prevalence of high and low empathy among residents as most studies only report a mean score with different empathy questionnaires.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first Canadian study to evaluate empathy and quality of educational environment with two validated survey tools. While our response rate was overall low, the impact may be mitigated by representation from every Canadian emergency medicine program and every postgraduate year. The survey responses were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic which could have independently affected both the scoring of educational environment and empathy. The opt-in nature of the survey may introduce sampling biases which could potentially skew results.

Implications

Empathy is linked to more positive patient encounters and outcomes, and it is concerning that almost 1 in 3 emergency medicine residents were found to have low empathy. While empathy is not a surrogate marker for burnout, a 2021 meta-analysis by Naji et al. found a very concerning global burnout rate of 47.3% among residents [2]. Should empathy truly be a protective factor against burnout this raises a red flag to medical education leaders to consider incorporating ways to increase empathy, along with other protective factors against burnout, among medical residents.

It is encouraging the quality of the postgraduate educational environment was rated highly across Canada by emergency medicine residents both on and off service. While quality of educational environment was not found in this study to be associated with empathy, this study contributes one more piece of information to elucidate how each of these factors may affect the other.

Conclusion

This national survey of Canadian emergency medicine residents explored the quality of postgraduate educational environment and empathy using two instruments with previously demonstrated evidence of validity. Residents rated the quality of their educational environment well. Nearly 30% were found to have low empathy. There was no association between empathy and quality of educational environment. Further research is needed to elucidate modifiable factors contributing to the development of low empathy in emergency medicine residents.

References

Stehman CR, Testo Z, Gershaw RS, Kellogg AR. Burnout, drop out, suicide: physician loss in emergency medicine, part I. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(3):485–94. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2019.4.40970.

Naji L, et al. Global prevalence of burnout among postgraduate medical trainees: a systematic review and meta-regression. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(1):E189–200. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20200068.

Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Burn Res. 2017;6:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.06.003.

Robieux L, Karsenti L, Pocard M, Flahault C. Let’s talk about empathy! Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(1):59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.024.

Neumann M, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Acad Med. 2011;86(8):996. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615.

Schönrock-Adema J, Visscher M, Raat ANJ, Brand PLP. Development and validation of the scan of postgraduate educational environment domains (SPEED): a brief instrument to assess the educational environment in postgraduate medical education. PLoS ONE. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137872.

van Vendeloo SN, et al. The learning environment and resident burnout: a national study. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(2):120–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0405-1.

Spreng RN, McKinnon MC, Mar RA, Levine B. The toronto empathy questionnaire. J Pers Assess. 2009;91(1):62–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802484381.

Roling G, et al. Empathy, well-being and stressful experiences in the clinical learning environment. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(11):2320–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.04.025.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Alexandra Hamelin for graciously translating the surveys into French.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maniuk, T., Cheung, W.J., Fischer, L. et al. The relationship between empathy and the quality of the educational environment in Canadian emergency medicine residents. Can J Emerg Med 24, 493–497 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00297-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00297-x