Abstract

Objective

To identify risk factors associated with persistent concussion symptoms in adults presenting to the emergency department (ED) with acute mild traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial conducted in three Canadian EDs whereby the intervention had no impact on recovery or healthcare utilization outcomes. Adult (18–64 years) patients with a mild TBI sustained within the preceding 48 h were eligible for enrollment. The primary outcome was the presence of persistent concussion symptoms at 30 days, defined as the presence of ≥ 3 symptoms on the Rivermead Post-concussion Symptoms Questionnaire.

Results

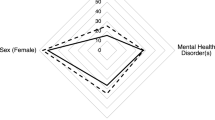

Of the 241 patients who completed follow-up, median (IQR) age was 33 (25 to 50) years, and 147 (61.0%) were female. At 30 days, 49 (20.3%) had persistent concussion symptoms. Using multivariable logistic regression, headache at ED presentation (OR: 7.7; 95% CI 1.6 to 37.8), being under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of injury (OR: 5.9; 95% CI 1.8 to 19.4), the injury occurring via bike or motor vehicle collision (OR: 2.9; 95% CI 1.3 to 6.0), history of anxiety or depression (OR: 2.4; 95% CI 1.2 to 4.9), and numbness or tingling at ED presentation (OR: 2.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 5.2), were found to be independently associated with persistent concussion symptoms at 30 days.

Conclusions

Five variables were found to be significant predictors of persistent concussion symptoms. Although mild TBI is mostly a self-limited condition, patients with these risk factors should be considered high risk for developing persistent concussion symptoms and flagged for early outpatient follow-up.

Résumé

Objectifs

Identifier les facteurs de risque associés aux symptômes persistants consécutifs à une commotion cérébrale chez les adultes se présentant au service des urgences avec un traumatisme cranio-cérébral aiguë.

Méthodes

Il s'agissait d'une analyse secondaire d'un essai contrôlé randomisé mené dans trois services d'urgence Canadien, dans lequel l'intervention n'a eu aucun impact sur le rétablissement ou les conséquences d'utilisation des soins de santé. L'essai clinique a été effectuée sur les patients adultes (âgés de 18 à 64 ans) avec un traumatisme cranio-cérébral léger (TCCL) soutenu dans les 48 heures précédentes. Le critère principal de jugement était la présence des symptômes de traumatisme crânien 30 jours après la commotion, définie comme la présence d'au moins 3 symptômes dans le questionnaire Rivermead sur les symptômes post-commotionnels.

Résultats

Parmi les 241 patients qui ont terminé le suivi, l'âge médian (EI) était de 33 ans (25 à 50) et 147 (61,0 %) étaient des femmes. À 30 jours, 49 (20,3 %) présentaient des symptômes persistants. En utilisant une régression logistique multivariée, des maux de tête à la présentation aux services d'urgence (OR: 7,7; IC à 95 % : 1,6 à 37,8), être sous l'influence de drogues ou d'alcool au moment de la commotion (OR : 5,9; IC à 95 % : 1,8 à 19,4), la blessure survenue à la suite d'une collision à vélo ou à moteur (OR : 2,9; IC à 95 %: 1,3 à 6,0), des antécédents d'anxiété ou de dépression (OR : 2,4; IC à 95 % : 1,2 à 4,9) et un engourdissement ou des picotements lors de la présentation aux services d'urgence (OR : 2,4; IC à 95 % : 1,1 à 5,2), se sont avérés être indépendamment associés aux symptômes persistants consécutifs à une commotion cérébrale à 30 jours

Conclusions

Cinq variables se sont révélées être des indicateurs significatifs des symptômes persistants consécutifs à une commotion cérébrale. Bien que le TCCL soit principalement une condition auto-limitée, les patients présentant ces facteurs de risque doivent être considérés comme à haut risque de développer des symptômes persistants et signalés pour un suivi ambulatoire précoce

Similar content being viewed by others

References

CDC. Injury prevention & control: traumatic brain injury. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/data/rates.html. Accessed June 15, 2016.

Jagoda AS, Bazarian JJ, Bruns JJ Jr, et al. American College of Emergency Physicians; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical policy: neuroimaging and decision making in adult mild traumatic brain injury in the acute setting. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(6):714–48.

Marshall S, Bayley M, McCullagh S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for mild traumatic brain injury. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:257–67.

Scorza KA, Raleigh MR, O’Connor FG. Current concepts in concussion: evaluation and management. Am Fam Phys. 2012;85(2):123–32.

Alves W, Macciocchi S, Barth J. Postconcussive symptoms at one year following minor traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;8(3):48–59.

Deb S, Lyons I, Koutzoukis C. Neuropsychiatric sequelae one year after minor head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:899–902.

Lucas S. Headache management in concussion and mild traumatic brain injury. PMR. 2011;3(10 Suppl 2):S406–12.

Stulemeijer M, van der Werf S, Borm G, Vos P. Early prediction of favorurable recovery 6 months after mild traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:936–42.

Sheedy J, Harvey E, Faux S, et al. Emergency department assessment of mild traumatic brain injury and the prediction of postconcussive symptoms: a 3-month prospective study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(5):333–43.

Faux S, Sheedy J, Delaney R, et al. Emergency department prediction of post-concussive syndrome following mild traumatic brain injury: an international cross-validation study. Brain Inj. 2011;23(5):531–42.

Ponsford J, Cameron P, Fitzgerald M, et al. Predictors of postconcussive symptoms 3 months after mild traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology. 2012;26(3):304–13.

Velikonja D, Quon D, Baldisera T et al. (2018) Standards for high quality post-concussion care – post concussion care pathway. Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation; 2018. http://concussionsontario.org/standards/tools-resources/post-concussion-care-pathway/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

Leddy JJ, Haider MN, Ellis MJ, et al. Early subthreshold aerobic exercise for sport-related concussion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):319–25.

Varner C, Thompson T, de Wit K, Borgundvaag B, Houston R, McLeod S. A randomized trial comparing prescribed light exercise to standard management for emergency department patients with acute mild traumatic brain injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;22:6.

McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. (2013) Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sports Med 47: 250–258.

Voormolen D, Cnossen M, Polinder S, von Steinbuechel N, Vos P, Haagsma J. Divergent classification methods of post-concussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury: prevalence rates, risk factors, and functional outcome. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35:1233–41.

Eyres S, Carey A, Gilworth G, Neumann V, Tennant A. Construct validity and reliability of the rivermead post concussion symptoms questionnaire. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(8):878–87.

Plass AM, Van Praag D, Covic A, et al. The psychometric validation of the Dutch version of the Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ) after traumatic brain injury (TBI). PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0210138.

Sveen U, Bautz-Holter E, Sandvik L, Alvsåker K, Røe C. Relationship between competency in activities, injury severity, and post-concussion symptoms after traumatic brain injury. Scand J Occupat Ther. 2010;17(3):225–32.

Broshek D, DeMarco A, Freeman J. A review of post-concussion syndrome and psychological factors associated with concussion. Brain Inj. 2015;29(2):228–37.

Madhok D, Yue J, Sun X, et al. Clinical predictors of 3- and 6-month outcome for mild traumatic brain injury patients with a negative head CT Scan in the emergency department: a TRACK-TBI Pilot Study. Brain Sci. 2020;10:269.

Seabury SA, Gaudette É, Goldman DP, et al. Assessment of follow-up care after emergency department presentation for mild traumatic brain injury and concussion: results from the TRACK-TBI study. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(1):e180210.

Bell KR, Hoffman JM, Temkin NR, et al. The effect of telephone counselling on reducing posttraumatic symptoms after mild traumatic brain injury: a randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:1275–81.

Eliyahu L, Kirkland S, Campbell S, Rowe BH. The effectiveness of early educational interventions in the emergency department to reduce incidence or severity of post-concussion syndrome following a concussion: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(5):531–42.

Funding

This project was supported by grants from the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board of Ontario and the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CV contributed to study concept and design, interpretation of the data, drafting and editing the manuscript, and acquisition of funding. CT contributed to acquisition of the data, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript, and statistical expertise. KD contributed to study design, acquisition of data, and editing the manuscript. BB contributed to study concept and design and editing the manuscript. RH contributed to study design and acquisition of the data. SM contributed to study concept and design, acquisition of funding, data analysis and interpretation, and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

CV, CT, KD, BB, RH, and SM report no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Varner, C., Thompson, C., de Wit, K. et al. Predictors of persistent concussion symptoms in adults with acute mild traumatic brain injury presenting to the emergency department. Can J Emerg Med 23, 365–373 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-020-00076-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-020-00076-6