Abstract

Natural resource degradation poses a major challenge to the sustainable livelihoods of farmers in developing countries, hindering progress toward achieving sustainable rural development. Watershed development and management practices (WDMPs) are powerful tools for enhancing sustainable rural development in developing countries. These practices have been shown to significantly improve livelihoods and food security. This research examined how WDM programs help achieve sustainable development in rural areas, focusing on examples from Ethiopia. This study used a systematic literature review (SLR) approach following a PRISMA review protocol. The research question was formulated using the CIMO (context, intervention, mechanisms, and outcomes) approach: “Does the watershed development and management (WDM) initiative lead to sustainable rural livelihoods?” Considering this research question, the findings indicated that WDM contributes to the socioeconomic and environmental sustainability of rural communities. It does this by enhancing households’ livelihood in terms of income generation, employment opportunities, agricultural productivity, and improvements in social services and infrastructure, as evidenced by numerous studies, thereby leading to better livelihoods and food security. This research also emphasizes the importance of community participation and supportive policies and legal frameworks for successful WDM. Overall, the systematic literature review highlights the potential of WDMPs in promoting sustainable rural development in developing countries such as Ethiopia while also highlighting the need for a supportive policy and institutional environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The sustainable use of natural resources is becoming an increasingly urgent concern globally, as many of these resources face the threat of depletion [1, 2]. The depletion of natural resources can profoundly affect human beings and jeopardize the sustenance and welfare of those who rely on these resources [3, 4]. Indeed, farmers in developing countries’ highlands depend on natural resources for their well-being. Four-fifths of the world’s poor live in rural areas, and most depend on natural resources for their livelihoods [5,6,7]. Sub-Saharan Africa in particular faces significant vulnerability regarding the depletion of natural resources [8, 9].

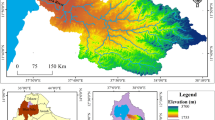

The depletion of natural resources is a critical issue in Ethiopia [10]. The highlands in the country are among the most degraded lands in Africa [11]; the ecology in many parts of the highlands is considerably damaged, sometimes beyond recovery [12]. Ethiopia has experienced high rates of land degradation, soil erosion, deforestation, and frequent droughts [10, 13,14,15]; central highlands are among the areas experiencing persistent declines in the potential productive capability of watershed resources [16,17,18,19,20,21]. In light of these challenges, both the government and nongovernmental organizations have launched several initiatives aimed at natural resource development and management to alleviate the impact and address these issues. Among these approaches, WDM have evolved significantly over time.

A watershed is a natural land unit that collects water and channels it through a common outlet via a network of drains [22, 23]. It is a hydrologic unit and is used as a physical-biological or socioeconomic-political unit for planning and managing natural resources for increasing productivity, generating employment, overall socioeconomic development and, consequently, the well-being of the community [22, 24,25,26]. Watershed development is defined as programs involving targeted technical interventions, such as afforestation, construction of check dams, and soil conservation practices. These interventions aim to enhance the productivity of specific natural resources within the watershed, with the objective of optimizing resource utilization while ensuring sustainable water availability [27,28,29]. On the other hand, watershed management refers to the holistic understanding and regulation of hydrological relationships within a watershed. Rather than solely investing in physical interventions, socioeconomic and ecological factors are considered. The emphasis is on safeguarding resources from degradation, with the objective of maintaining ecological balance, preventing resource depletion, and promoting sustainable livelihoods [27, 30, 31].

Recognizing the interdependence between technical interventions and subsequent management efforts, this study adopts the combined term watershed development and management (WDM) to underscore the necessity of integrating both ecological and socioeconomic aspects for effective watershed governance. Initially, the focus was primarily on physical aspects, such as reforestation and soil conservation, which contribute to climate resilience by mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events and maintaining ecosystem services crucial for agriculture [32,33,34]. However, this approach has transformed into a holistic perspective integrating social, economic, and environmental dimensions. Today, effective WDM encompasses the coordinated management of land, water, biota, and other resources within a defined geographical area [22, 35].

As the world collectively tackles urgent environmental, social, and economic issues, strategic WDM plays a crucial role. This approach, supported by research from various scholars [27, 36,37,38,39], is instrumental in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs). By safeguarding natural resources, promoting sustainable livelihoods, and bolstering resilience, effective WDM contributes significantly to the SDGs. The significance of WDM in achieving sustainable rural development is explored through the lens of the SDGs. The central focus of SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) from the perspective of watershed management lies in conserving natural resources. In the context of SDGs 6 and 15, watershed management serves as a preventive measure against soil erosion, deforestation, and habitat degradation. This approach promotes biodiversity and preserves ecosystem functions. Moreover, watershed management plays a critical role in sustaining freshwater reservoirs, which are essential for human settlements, agriculture, and ecological balance. The scope of SDG 1 (No Poverty) emphasizes the enhancement of livelihoods. Effective watershed management practices lead to increased agricultural productivity, thereby generating livelihood opportunities for rural communities [40,41,42].

Furthermore, through the lens of watershed management, SDG 13 (climate action) emphasizes the strengthening of resilience. Proficient watershed management significantly boosts climate resilience and communal well-being. This is evident in SDG 13, where effective watershed management mitigates climate-induced challenges such as floods and regulates water flow, thereby fortifying community resilience against environmental adversities. SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) underscores the role of well-managed watersheds in bolstering sustainable livelihoods by ensuring water access for industries, fisheries, and tourism [40, 42]. Additionally, within the ambit of SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), competent watershed management reduces vulnerability to natural disasters, thereby fostering safer urban environments [40,41,42].

WDM are crucial for achieving sustainable rural development, particularly in developing countries; Ethiopia, a developing country, has acknowledged the significance of WDM in tackling challenges and promoting sustainable rural development since mid-1970 [17, 38, 43,44,45,46,47,48]. These efforts aim to restore natural resources, enhance agricultural productivity, and improve the livelihoods of people living in watershed areas. By implementing integrated WDM practices (WDMPs), Ethiopia seeks to be effective in terms of soil conservation, reforestation, and water harvesting; communities can improve their resilience to the impacts of climate change, enhance their food security and improve agricultural productivity in the country [37, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. However, despite the existence of actionable research, these efforts have yet to translate into substantial enhancements in sustainable rural development regarding livelihood outcomes. These outcomes include income and employment generation, agricultural productivity, social services, infrastructure, and food security within the country. Consequently, this study aimed to identify a comprehensive framework for optimizing WDMPs, specifically focusing on the Ethiopian central highlands.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows: In sect. 2, the methodology of the study is discussed. Section 3 presents the study’s results, and Sect. 4 presents a discussion of the findings. Sections 5 and 6 present the conclusions and recommendations, respectively.

2 Methodology

This study aims to contribute new knowledge to the literature by addressing how watershed development is integral to sustainable rural development. This study employs the pragmatist worldview [55, 56]. Pragmatism explores the origin, nature, and limits of human understanding, prioritizing practical implications over abstract truths [56,57,58,59,60]. Pragmatic theories emphasize the importance of practical aspects when assessing the role of WDM in sustainable rural development. This study employed a systematic literature review (SLR) as the research technique. This approach contributes to the current understanding of social aspects of sustainable rural development through enhanced watershed management practices and to finding, critiquing, and synthesizing the results of all available studies to establish overall findings for a question. SLRs provide a structured approach for reviewing the literature and follow a detailed process. The methods used were predefined, and the research and reporting followed specific guidelines and frameworks, as highlighted by [61]. This method involves establishing a protocol beforehand, applying rigorous search strategies across multiple databases, and conducting a critical appraisal of selected studies to address a specific research question [62].

While prior research has explored the potential benefits of watershed management, these studies lacked a focus on sustainable rural development or did not specifically address households in developing countries such as Ethiopia. Poonia and Singh [63] for example, focused on groups in India, while Worku and Tripathi [64] and Abebaw [65] focused on Ethiopia using traditional review methods and did not focus on the role of watershed management in sustainable rural development. The scarcity of research, according to the researchers, on the issue within a developing country context such as Ethiopia prompted this SLR, aiming to bridge the knowledge gap and offer a comprehensive understanding of the literature.

This study was guided by a preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) review protocol. Based on the review protocol, the authors started the SLR by formulating an appropriate research question for the review. The research question was formulated using the context, intervention, mechanisms, and outcomes (CIMO) approach. The CIMO framework is more applicable in nonmedical research where there is a limited requirement to compare interventions [66]. This study investigates the impact of WDM (intervention) on achieving sustainable rural development (outcome) through livelihood outcomes (mechanisms) for rural communities (context). The final question read as follows: “Does watershed development and management initiative lead to sustainable rural livelihoods?” This question examines the role of WDM in contributing to sustainable rural livelihoods. The question also examines the various benefits that households are likely to gain from WDM in terms of livelihood outcomes. The question also touches on community participation and policy to ensure the sustainability and conservation of watershed resources to meet the needs of the community.

Following the research question development, the next step involved a “web search” using keywords and “Boolean operators”. This search targeted articles relevant to the research question and qualitative variables. Keywords such as “watershed development”, “watershed management”, “sustainable rural development”, “livelihood outcome”, and “food security” were used. The purpose of using the keywords was to enhance the accuracy of the literature. The Boolean operators approach was also used to combine search terms in ways that broaden and limit the search results to the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. The primary sources of information for this review were the electronic journal databases Web of Science, Google Scholar, Scopus, and WorldCat for peer-reviewed articles, books, and gray literature. The search strategy was continuously revised by trial and error until the databases yielded the maximum number of articles for screening. Based on the results of the first stage of screening, a literature search revealed a total of 1132 articles, of which 356 were from the Web of Science, 235 were from Scopus, 465 were from Google Scholar, and 76 were from other methods. All bibliographical details were imported into the EndNote 20 reference manager to manage the references and eliminate duplications. The next stage of the method involved selecting relevant articles. Duplicates were removed first, and the authors applied specific criteria (detailed in Table 1) to include or exclude studies. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select relevant studies for this research are detailed in Table 1. This table outlines the specific criteria considered for the included and excluded studies.

In the first phase, 735 articles remained for further screening, while others were eliminated from the review at this stage because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Next, article screening was performed by reading titles and abstracts, and in some cases, the entire text manually relevant to this study and irrelevant articles were removed, resulting in 277 potentially relevant articles. However, not all these articles were eligible for the study. A total of 243 articles were rejected for being ineligible or removed for other reasons, such as the year of publication, and subjected to further evaluation to identify those with specific answers to the research question. A total of 34 articles met the final criteria and were selected based on their relevance and accuracy in answering the research question. Following the PRISMA guidelines, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to select relevant studies. The selection process is visualized in a flowchart in Fig. 1.

2.1 Data analysis

This study applied a thematic analysis of the SLR. The retrieved articles (n = 34) were classified into various critical dimensions for analysis, as shown in Fig. 1. The main classifications included title, authors, region, and main findings. The analysis involved examining each of the findings to determine how they relate to sustainable rural development. This study aimed to determine whether WDM are correlated with or support sustainable rural development. Each of the findings was carefully examined to determine the relationship between watershed and sustainability.

This research asks, “Does the watershed development and management initiative lead to sustainable rural development?” Considering the research question of this research, the findings indicate that WDM contributes to the socioeconomic and environmental sustainability of the rural community by enhancing households’ livelihoods in terms of income generation, employment opportunities, agricultural productivity, and improvements in social services and infrastructure, as evidenced by numerous studies, thereby improving livelihoods and food security. The research findings emphasize the importance of community participation and policies and legal frameworks governing WDM. Finally, the study synthesized the findings by exploring key themes such as assessing community livelihood status, understanding the interplay between livelihood assets and watershed practices, evaluating the role of watershed development in socioeconomic aspects, measuring household food security, measuring community participation, and analysing relevant policies and legal frameworks on WDM.

3 Results

3.1 Background of the selected articles

Many studies have focused on watershed management in Ethiopia and India. Of the 34 articles reviewed, 15 explored initiatives in Ethiopia, and 13 explored initiatives in India. The remaining studies covered a wider range of regions, including China, Tanzania, South Africa, Thailand, and Vietnam, often in combination. This suggests a significant emphasis on WDM in the two countries of Ethiopia and India. The reviewed articles span a range of publication dates, with the earliest published in 2002 and the most recent appearing in 2024 (the current year). One was published in 2002, two in 2004, two in 2005, one in 2006, one in 2008, four in 2009, two in 2010, one in 2011, four in 2014, one in 2014, four in 2015, two in 2016, two in 2018, two in 2019, two in 2020, one in 2023, and one in 2024. This distribution suggests the inclusion of both established and more recent research on watershed management.

Following PRISMA guidelines, relevant articles were identified through a systematic review process. This resulted in a table summarizing the selected articles in Appendix. The table includes titles, authors, publication dates, study locations, and key findings of each study. To ensure the validity and applicability of the findings, the study further evaluated the evidence (detailed in Appendix) based on four criteria: strength, content validity, potential bias, and relevance to watershed development and sustainable rural livelihoods. Subsequently, based on the findings, the researcher constructed a diagram (Fig. 2) that explained how well-managed watersheds create a solid foundation for sustainable rural development. WDM initiatives have a direct impact on the sustainable rural development of communities through livelihood assets, thereby affecting household income and employment generation capacity, agricultural productivity, social services and infrastructure, and food security status in terms of food availability, access, food utilization, and stability. Community participation in WDM initiatives has a multifaceted impact on sustainable rural development both within a watershed and outside the watershed community. Policy is one of the master key factors, in addition to other considerations, that shape the outcome of initiatives for the sustainable rural development of a country.

4 Discussion

This study synthesized the effect of WDM on sustainable rural development by exploring several key themes. Based on the thematic analysis, six themes were developed: assessing community livelihood status (Sect. 4.1), understanding the interplay between livelihood assets and watershed practices (Sect. 4.2), evaluating the role of watershed development in socioeconomic aspects (Sect. 4.3), measuring household food security (Sect. 4.4), measuring community participation (Sect. 4.5), and analysing relevant policies and legal frameworks on WDM (Sect. 4.6).

4.1 Assessing the livelihood status of the community

This section focuses on evaluating the livelihood situation of households within the community. From a theoretical perspective, the sustainable livelihoods framework offers insights into assessing the livelihood status of communities. This framework highlights the importance of various livelihood assets (social, human, natural, physical, and financial capital) in achieving sustainable livelihoods [67, 68]. Individuals engaged in watershed management benefitted from improved access to natural resources, enhanced social networks, and increased income diversification, leading to greater livelihood resilience than that of nonpractitioners [50, 69].

According to Argaw, Abi [50], the status of the livelihood assets of the Shankur Tereqo and Mende-Tufesa watersheds (supposed as a control watershed) were comparatively analysed based on the five capital statuses of the livelihood assets. To measure the livelihood status of the households, eighteen variables representing the five livelihood assets of the households were selected. Human capital is measured by the age and education level of the household head, household size, and number of working members [70,71,72,73]. Financial capital refers to the household’s income sources, including annual agricultural and nonagricultural income, livestock holdings, and access to credit [68, 71, 73]. Natural capital focuses on households’ access to and quality of agricultural land, including total land area, fertility, and the availability of high-quality farmland [71,72,73]. Physical capital assesses the quality of housing, household possessions, access to public transportation, and proximity to markets [71,72,73,74]. Finally, social capital evaluates the community’s level of social interaction and support, including participation in social organizations, social networks, and the presence of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or local institutions [71,72,73, 75, 76].

Argaw, Abi [50] found no significant overall difference in livelihood status between households in the Mende Tufesa and Shankur Tereqo watersheds. However, there are variations in the different types of capital that contribute to livelihood status. The variations are depicted by the pentagon that states the livelihood status of the practitioners in Fig. 3 and non-practitioners in Fig. 4.

Livelihood status of the untreated watershed (based on [50])

Livelihood status of the treated watershed (based on [50])

The variation in livelihood status in terms of livelihood capital between the households in the study watersheds showed the following:

-

Financial and physical capital: Households in both watersheds scored low (below 0.33) on these measures, indicating a relatively poor state compared to the Shankur-Tereqo watershed.

-

Human and natural capital: These aspects showed some variation but still fell within the “average” range (0.33–0.66) for both watersheds.

-

Social capital: This measure stood out, with both watersheds scoring in the “good” category. This suggests a strong level of social interaction and support within the communities.

Another study by Siraw, Bewket [51] also revealed the significant contribution of WDM to livelihood benefits in terms of overall livelihood capital indices, with variations in the improvement of different livelihood capitals across different micro-watersheds and considerable improvements in natural and human capital. Studies have investigated the true effect of the initiative by analysing the livelihood status of the community using a sustainable livelihood framework. Focusing on the approach implemented by Argaw, Abi [50], this study suggested conducting a comparative analysis of the livelihood status of households practising and those not practising watershed management, which revealed a significant difference. As households engaged in watershed initiatives often have diversified livelihood strategies and access to natural resources, nonparticipants face greater vulnerabilities and dependence on external support [50, 77, 78]. Individuals engaged in watershed management often exhibit greater resilience and livelihood diversification than those not involved, as they benefit from improved access to natural resources and sustainable land management practices [79, 80].

To enhance the rural livelihoods of households in watersheds, optimizing the WDM is expected. Rural livelihoods in Ethiopia are experiencing widespread challenges, including limited access to education, healthcare, and basic infrastructure. Moreover, vulnerability to natural disasters such as droughts and floods exacerbates the plight of agricultural and livestock-dependent communities [51, 81]. Concerted efforts are imperative at the community and governmental levels to address these pressing issues. Interventions entailed enhancing access to education, healthcare, and potable water alongside strategic investments in infrastructure such as roads and electricity [51, 82]. Promoting sustainable agricultural practices and extending financial and technical support to smallholder farmers are pivotal steps toward resilience-building [83]. Crucially, community engagement may need to underpin the planning and execution of these initiatives to ensure their effectiveness and long-term sustainability.

4.2 The interconnection between livelihood assets and watershed practices

This section investigates how a community’s resources (livelihood assets) influence and is influenced by their WDMPs. The interconnection between livelihood assets and watershed management practices is a multifaceted relationship that plays a pivotal role in the sustainable development of communities. Livelihood assets within a sustainable livelihood framework encompass various tangible and intangible resources that individuals and communities utilize to support their livelihoods, including natural, human, social, physical, and financial assets [67, 68, 84]. Access to these assets plays a crucial role in influencing engagement in watershed development practices to enhance community resilience, promote sustainable resource management, and facilitate participation in watershed initiatives [50, 85,86,87].

The relationships between livelihood assets and WDMPs are bidirectional and dynamic. On the one hand, the availability and quality of livelihood assets significantly impact the effectiveness of watershed management interventions [88]. For instance, communities blessed with abundant natural resources and social capital—such as fertile soil and water—tend to be better prepared to implement sustainable land management practices and adapt to the effects of climate change, and their efforts have resulted in greater success and long-term sustainability [89, 90]. On the other hand, WDMPs can directly influence livelihood assets [50, 78]. When watershed management is effective, natural capital can be enhanced by improving soil fertility, water availability, and biodiversity. These improvements, in turn, support agricultural productivity and provide essential ecosystem services for livelihoods [91]. Additionally, community-based watershed management approaches empower local communities by creating income generation, capacity building, and collective decision-making opportunities. This empowerment strengthens these communities’ human and social capital [88]. Comparisons between Ethiopia, Nepal, and Indonesia highlight the diverse interplay of social, human, natural, physical, and financial capital in shaping community engagement and resilience [92,93,94].

Argaw, Abi [50] examined the relationships between livelihood assets and watershed development and management practices (WDMPs) using structural equation modelling (SEM). The analysis revealed that the WDMP generally had statistically significant and positive relationships with all livelihood assets. As depicted in Fig. 5, the WDMP had the highest correlation or significant positive relationship with natural capital (NC), with a path coefficient of 0.553, compared to livelihood assets. In contrast, it had the lowest correlation with social capital (SC), with a path coefficient of 0.232, yet a statistically significant positive relationship existed. Other human capital (HC), physical capital (PC), and financial capital (FC) had statistically significant and positive relationships with the WDMP according to standard estimation or path coefficients of 0.43, 0.378, and 0.336, respectively [50].

The diagram represents the interconnectedness between livelihood assets and the practices they use to manage their watershed (based on [50])

Ethiopia has the potential to enhance rural livelihood assets in several ways through WDMPs. First, these practices can improve the availability and accessibility of water resources, which are critical for supporting agriculture and livestock production. This can increase the productivity and income of farmers and herders, thereby enhancing their livelihood assets. Second, watershed management practices can help conserve soil and water resources, prevent soil erosion and improve soil fertility. This can lead to better crop yields and improved food security, which can also enhance livelihood assets. Third, watershed development practices can promote the use of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power, which can provide alternative energy sources for rural communities. This can reduce their dependence on nonrenewable energy sources and enhance their economic and social assets. Overall, adopting WDMPs can significantly positively impact rural livelihood assets in Ethiopia and promote sustainable development in the region.

Studies suggest that WDMPs may hold promise for improving the lives of people in developing countries such as Ethiopia. These practices could enhance rural livelihoods in several ways.

-

Improved agriculture and livestock production: By enhancing the availability and accessibility of water, watershed management practices could support agriculture and livestock production [95, 96]. This might lead to increased productivity and income for farmers and herders, ultimately contributing to their overall well-being.

-

Soil conservation and fertility: WDMPs have the potential to conserve soil and water resources, prevent erosion, and improve soil fertility [82, 97]. This could result in better crop yields and improved food security, further benefiting rural livelihoods.

-

Source of energy: These practices might also encourage the use of renewable energy sources such as solar energy, providing alternative energy options for rural communities [50, 97]. This could lead to a reduction in the dependence on non-renewable sources, potentially boosting economic and social well-being.

In conclusion, adopting WDMPs appears to be a promising approach to positively impact rural livelihoods in Ethiopia and contribute to the region’s sustainable development.

4.3 Role of watershed development in socioeconomic aspects

This section explores how developing and managing watersheds contribute to positive social and economic outcomes for the community. Economic development theories, such as human capital and agricultural development theories, offer insights into how watershed development contributes to socioeconomic aspects [98, 99]. Human capital and agricultural development are intertwined concepts; human capital development theories highlight the crucial role of investing in farmers’ knowledge, skills, health, and empowerment to achieve sustainable agricultural development. This approach goes beyond physical capital (machinery, equipment) and recognizes the human factor as a key driver of progress [100]. Watershed development initiatives can lead to increased income generation, employment opportunities, and agricultural productivity through improved access to water resources, soil conservation measures, and sustainable land management practices [101,102,103,104].

Watershed development initiatives significantly contribute to the socioeconomic development of developing countries across several key areas, including income generation, employment opportunities, agricultural productivity, and improvements in social services and infrastructure, as evidenced by numerous studies, thereby improving livelihoods and reducing poverty [36, 83, 96, 105].

Research shows that watershed development projects increase local communities’ income generation opportunities [105, 106]. For instance, watershed management activities such as soil conservation and water harvesting have enhanced land productivity, enabling farmers to cultivate higher-value crops and generate additional income. Additionally, the implementation of sustainable agricultural practices, such as agro forestry and integrated crop-livestock systems, has been found to improve crop yields and diversify income sources [50, 107,108,109]. It creates employment opportunities by involving local communities in activities such as afforestation and infrastructure building; these initiatives significantly contribute to poverty reduction and foster social inclusion [50, 107, 110].

Watershed development interventions improve agricultural productivity by enhancing soil fertility, water availability, and land management practices. For instance, implementing soil and water conservation practices prevents soil erosion and enhances soil moisture retention [97]. This, in turn, results in higher crop yields and greater agricultural resilience to climate fluctuations [83]. Additionally, the adoption of WDM initiatives has been proven to enhance agricultural productivity and food security [111,112,113].

Several studies, such as Kerr [114], Hope [115], Hassan, Alam [116], Ibrahim, Hassan [117], Surya, Syafri [118], Herrera, Ellis [119], Norton, Seddon [120], Adeniran, Daniell [121], suggest that watershed development projects can have a positive influence on social services and infrastructure in rural areas. Investments in water supply systems, irrigation infrastructure, and rural roads may lead to improved access to essential services and markets, potentially enhancing the quality of life of local communities. Furthermore, activities focused on strengthening social services such as healthcare, education, and sanitation have been shown to potentially contribute to overall human development and well-being.

Although WDM initiatives hold promise for building resilient and prosperous communities in the long term, the extent and nature of these impacts vary across countries. While these initiatives have the potential to generate income, create employment opportunities, enhance agricultural productivity, and improve social services and infrastructure, the specific results depend on various factors, such as contextual nuances in policy formulation [122, 123], institutional capacity [2], governance frameworks [124], implementation strategies, and socioeconomic contexts [27, 122, 124].

Argaw, Abi [50] examined the impacts of the WDMP on livelihood outcomes in terms of income generation, employment opportunities, agricultural productivity, improvement in social services, and infrastructure through SEM. The study suggested that the WDM program may be a promising tool for households in the study area. The program appears to have the potential to contribute to increased income and job creation by supporting various aspects of their well-being, known as livelihood assets. These assets include skills and knowledge (human capital), access to financial resources (financial capital), infrastructure and tools (physical capital), and environmental resources (natural capital). The study also revealed a potential increase in agricultural productivity as a result of the WDMPs. This could be linked to improved practices in land and water conservation, leading to greater use of double cropping, a shift towards more intensive cropping systems, and ultimately, greater crop production. Finally, the study suggested a positive association between the program and improved access to social services and infrastructure for participating households. This could be due to the overall enhancement of their livelihood assets, particularly in terms of natural resources and social networks. Figure 6 shows the SEM path coefficients for WDMPs and their standardized direct effects on the five livelihood assets and the indirect effects of income and employment generation, agricultural productivity, and social services and infrastructure.

The diagram depicts the influence of watershed development and management practices on a community’s socioeconomic aspects, mediated by livelihood assets (based on [50])

According to the findings from studies, WDM initiatives play an important role in developing countries, specifically in Ethiopia; they have helped improve the livelihoods of the rural population by providing them with access to generate employment opportunities and helping increase and diversify the income sources of the household as well as improving the well-being of people [50, 82, 83]. They improved the agricultural productivity of households in rural areas [95,96,97, 125]. This might lead to increased productivity and income for farmers and herders, ultimately contributing to their overall well-being. The government of Ethiopia has been actively promoting WDM programs and has invested heavily in building infrastructure to support these programs [64, 65, 83]. As a result, there has been a noticeable improvement in the socioeconomic conditions of people living in rural areas of Ethiopia [126]. Thus, investing in WDM can significantly impact the overall socioeconomic development of communities and regions.

4.4 Assessing the household food security status of the community

This section compares the food security situation of households between WDM practitioners and non-practitioners. The food systems approach highlights the interconnectedness of all parts of the system and the need for a holistic approach to achieving food security [49, 127, 128]. WDM contributes to a more resilient food system. It helps conserve soil fertility and water resources, which are crucial for sustainable food production. Additionally, by improving water quality and reducing erosion, it protects downstream agricultural areas. This holistic approach strengthens the entire food system, contributes to food security, and offers a valuable lens for analysing the role of WDM in achieving food security and evaluating the food security status of households within WDM initiatives.

In developing countries, household food security status can vary significantly between communities in treated watersheds and those in untreated watersheds due to several interconnected factors. Participants in WDM programs usually have a more favourable food security status than nonparticipants. Interventions such as soil conservation, water harvesting, and agro forestry within watersheds help support sustainable farming practices. They lead to improved agricultural productivity, increased crop yields, a variety of food sources, and greater resilience to climate fluctuations [34, 129,130,131,132,133,134].

Households practicing WDM experience better food security, and these interconnected benefits underscore the importance of investing in sustainable WDM to enhance food security in vulnerable communities. For instance, interventions such as soil conservation, afforestation, and water harvesting are crucial for enhancing water availability and maintaining water quality within watersheds. As a result, they enable more dependable irrigation practices, especially during dry periods. This, in turn, leads to increased agricultural productivity and ensures a diverse food supply for households. Furthermore, contour ploughing, terracing, and agro forestry help prevent soil erosion, conserve soil moisture, and enhance soil fertility. Healthy soils support better crop yields, thus increasing food production and contributing to household food security [27, 47, 135,136,137].

A study by Naji, Abi Teka [138] measured the impacts of the WDMP on household food security status using the household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) and household dietary diversity score (HDDS). This study disaggregated the results among WDM practitioners and non-practitioners; the HFIAS results are presented in Fig. 7, and the HDDS results are shown in Fig. 8.

HFIAS survey results (based on [138])

HDDS survey results (based on Naji, Abi Teka [138])

The HFIAS and HDDS results painted a concerning picture of food insecurity in the study area. The HFIAS survey results (Fig. 6) revealed that a significant portion of households (over 70%) worried that food would run out and ate only a few kinds of food. A substantial number of households (over 35%) experienced an actual food shortage, and some households (over 15%) had gone to sleep hungry more than once. Among the communities, 84.94% were food insecure at various levels (mild, moderate, or severe), of which 54.33% were found in the Mende-Tufesa watershed area. The study calculates the household food insecurity access incidence (HFIAP) to assess overall food insecurity. The results were concerning: only 15.1% of respondents were classified as food secure. In contrast, the number of severely food insecure households was three times greater. These households were forced to cut back on meal sizes or the number of meals they ate frequently. Additionally, some even experienced harsher food insecurity conditions, such as going a whole day without eating [138].

This study further implemented the HDDS food security measurement tool to assess dietary quality. Figure 7 shows that a significant portion (31.7%) of households had low dietary diversity. This means that their diets lacked variety and essential nutrients. However, there were also positive findings: 42.3% of households had medium dietary diversity, and 26% even achieved high dietary diversity. Overall, the average HDDS score was 4.83, indicating a medium level of dietary diversity for the study area. This suggests that households typically consume approximately five different food groups on average. The study clearly showed that the household food security status of rural households differed between Shankur-Tereqo and Mende-Tufesa. These findings support those of previous studies showing that household practices related to watershed initiatives were more conducive to food security for households than for non-practices households in the study area [138].

An assessment of household food security within watershed communities revealed a multifaceted interplay of factors. These factors are influenced by the agro-ecological conditions (such as climate, soil fertility, and water availability), institutional contexts (including land tenure policies, market access, and government support programs), and socioeconomic dynamics (such as income levels, education, and social safety nets) of the community. Comparative analyses between Ethiopia, India, and Malawi can shed light on the diverse determinants that shape food security outcomes across different contexts. This highlights the need for interventions that are tailored to the specific circumstances of each community [139,140,141].

According to the findings from the studies, watershed development initiatives play an important role in developing countries, specifically in Ethiopia; they have helped improve the household food security of the rural population. WDM interventions within watersheds help support sustainable farming practices and lead to improved agricultural productivity, increased crop yields, a variety of food sources, and greater resilience to climate fluctuations [47, 83, 112, 125, 126, 130, 138, 142]. Investing in watershed development initiatives holds promise for enhancing household food security across communities and regions. This is likely achieved through improved WDM and potentially increased agricultural productivity.

4.5 Assessing the community participation level

This section focuses on assessing the role of community participation in watershed intervention for sustainable rural development. From a theoretical standpoint, social capital theory offers insights into the level of community participation in watershed development endeavors. Robust social connections, trust, and collaboration among community members enable effective engagement in decision-making, execution of watershed initiatives, and durability of interventions over time [143, 144].

Community participation refers to the involvement of residents, including community leaders, farmers, women, youth, and other stakeholders, in watershed management project planning, implementation, and decision-making processes. Community participation is essential for the success of watershed development initiatives because it fosters ownership, enhances local knowledge and capacity, promotes social cohesion, and ensures the sustainability of interventions [145,146,147,148]. Community participation in watershed development in developing countries is facilitated through various mechanisms and approaches aimed at engaging local communities in decision-making processes, project planning, implementation, and monitoring [146, 149, 150].

The study conducted by Naji, Abi Teka [148] measured the extent to which people participated in the WDMP across the planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation phases and applied a People’s Participation Index (PPI). The findings portrayed in the chart (Fig. 9) indicated that non-practitioners exhibited moderate participation, while WDM practitioners were highly engaged. Overall, the PPIs were categorized as moderate, reflecting the diverse roles and responsibilities assumed by households during watershed implementation and contributing to their significant stakes in multiple activities within the study area. Figure 9 presents a chart comparing the level of community participation between WDM practitioners and non-practitioners.

Community participation level in watershed management (based on [148])

Community participation has emerged as a linchpin for the success of watershed initiatives, yet its dynamics vary widely across countries. Factors affecting the successful participation of the community in the implementation of watershed projects exhibit considerable heterogeneity, necessitating context-specific approaches. In the context of developing countries, community participation can be shaped by several factors [63]. These include local leadership and governance, community skills and technical capacity, perceived benefits and risks, cultural and social norms, access to resources and infrastructure, stakeholder engagement, communication and awareness, policy and institutional frameworks, and environmental degradation and climate change, all of which impact the success and sustainability of watershed development initiatives [151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164].

At the household level, various factors influence participation in WDM initiatives in developing countries. These factors include the socioeconomic status of the household head, educational level, land size, family size, perceived benefits and costs, institutional support, and extension services [145, 165,166,167,168,169,170]. Drawing on insights from various studies, it appears that several factors can play a significant role in the success and long-term sustainability of WDM initiatives. To encourage active participation from local communities, agricultural authorities at the local and regional levels can play a key role. This could involve providing training opportunities, fostering a sense of ownership among participants, and highlighting the long-term benefits for the community.

4.6 Policies and legal frameworks related to watershed development and management

The policies, strategies, programs, and legislative frameworks for watershed development and management (WDM) in developing countries vary significantly depending on the country’s specific context, political structure, environmental challenges, and socioeconomic conditions. However, many developing nations can observe some common themes and approaches. Theoretically, this study incorporates political ecology theory, which examines the political-economic factors that shape environmental governance, resource distribution, and access to decision-making processes [171]. It emphasizes the inherent “politicalness” of the environment, arguing that environmental degradation cannot be solely understood through scientific and technical lenses [172]. Political ecology offers a valuable lens for analysing WDM policies, programmes, and strategies. Ensuring alignment with local needs and environmental realities enhances the impact of WDM initiatives [173,174,175].

Strengthening the legal frameworks for WDM is crucial. It helps regulate land use, protect water resources, uphold community rights, and promote sustainable practices, ultimately enhancing watershed governance and resilience. Continuously assessing existing policies, programs, and strategies is essential for identifying strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement, leading to more effective interventions and better outcomes. Identifying gaps in current WDMPs and recommending policy options are vital for enhancing the effectiveness, sustainability, and long-term resilience of watershed management in developing countries [27, 43, 44, 93, 116, 137, 176].

Legal frameworks for WDM vary significantly across countries, reflecting differences in legal traditions, governance structures, and environmental policies. Comparative analyses among developing countries have shed light on diverse regulatory approaches and their implications for watershed governance [27, 177,178,179,180]. To effectively assess policies, programs, and strategies, as well as to identify gaps and recommend policy options, nuanced contextualization within each country’s socioeconomic and environmental context is essential. Furthermore, comparative studies have provided insights into the effectiveness of different approaches and underscore the importance of adaptive management and context-specific policy prescriptions tailored to local realities [39, 175, 180,181,182].

WDM plays a crucial role in sustainable development, especially in developing countries such as Ethiopia, where water scarcity and soil erosion are pressing concerns. Despite substantial efforts to enhance WDMPs, more policy execution is still needed in the country. While the government has crafted well-formulated policies, programs, and strategies, the true hurdle lies in their implementation. Legal provisions for watershed management, such as the Water Resources Management Policy and the Proclamation on Watershed Management, face significant challenges during execution. Bridging the gap between policy design and practical implementation is essential. Ensuring that formulated policies and strategies are translated into action is vital for achieving desired goals and positively impacting the environment and people.

One significant gap in WDM in the study area was the need for coordination among various government agencies involved in the process, and the absence of effective enforcement mechanisms and penalties weakens the impact of existing legal frameworks in WDM. This results in fragmented and inefficient programs. Establishing a national coordinating body with clear mandates and responsibilities for coordinating WDM across different sectors and at different government levels is crucial to addressing this issue. Another gap lies in the need for more participation of local communities in decision-making processes related to watershed management. Encouraging participatory approaches, such as community-based natural resource management, can empower communities to take ownership and responsibility for their watersheds.

Developing countries, including Ethiopia, have established appealing policies, strategies, programs, approaches, and legal frameworks for and related to WDM. However, practical execution of these methods remains challenging. Countries must address coordination and enforcement issues to ensure effective implementation and sustainable watershed management. Bridging the gap between policy formulation and execution is crucial, with active community involvement playing a key role. Investing in research and capacity building will also enhance evidence-based decision-making and policy effectiveness. Collaborative efforts among the government, academia, and civil society can drive positive changes in the country’s natural resource management and contribute to sustainable development and poverty reduction.

5 Conclusion

WDMPs have been shown to significantly enhance sustainable rural development, particularly in terms of livelihood and food security in developing countries. Wani and Ramakrishna [183] and Wani, Dixin [184] both highlighted the potential of these practices for improving rainwater use efficiency, reducing soil erosion, and increasing agricultural productivity and rural incomes. This approach, as discussed by [132] and [34], highlights the potential of community watershed programs for improving livelihoods and resilience, particularly in the face of climate change impacts. These programs have been successful in increasing agricultural productivity, doubling family incomes, and reducing runoff and soil loss.

Yoganand and Gebremedhin [185] and Naji, Abi Teka [148] further emphasized the role of participatory WDM in achieving sustainable rural livelihoods. Finally, Habtu [186] and Poonia and Singh [63] identify challenges such as poor institutional support and lack of participation in the promotion of watershed-based interventions and suggest key conditions for their revitalization, including institutional support, community participation, and capacity building. These studies collectively underscore the potential of WDMPs for promoting sustainable rural development while also highlighting the need for supportive policies and institutional environments.

Effective WDM are crucial for sustainable rural development, especially in developing countries such as Ethiopia, where various ecosystems and weather conditions pose significant challenges. It is essential for environmental conservation and directly contributes to achieving multiple SDGs. Recognizing the interconnectedness of natural systems and human well-being can create a more sustainable and resilient future. Advancing WDM in developing countries requires a holistic approach that integrates socioeconomic aspects, community participation, policy and institutional dimensions. By addressing the key elements outlined in this article and implementing the recommended policy options, countries could achieve more sustainable and resilient watershed management outcomes, contributing to the well-being of their people and the preservation of their natural resources. The findings highlight the critical role of watershed management in promoting sustainable development goals and provide valuable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers in developing countries.

6 Recommendations

Based on the findings, the following recommendations are made to enhance the effectiveness of WDM in developing countries:

-

Promote participatory approaches: The government should prioritize participatory approaches to WDM involving community members in decision-making. WDM thrives on community involvement. Local residents hold valuable knowledge of the land and its resources, fostering more effective solutions. When communities participate in decision-making, they become invested in the project’s success, ensuring its long-term viability. Participatory approaches consider the diverse needs of various stakeholders within a watershed, leading to fairer solutions. By empowering communities to manage their resources, these projects promote sustainability and local ownership. Despite these challenges, this research overwhelmingly supports participatory approaches for effective WDM.

-

Promote integrated approaches: The government should promote integrated WDM approaches that recognize the interconnectedness of environmental, social, and economic factors. Integrated watershed management (IWM) is a highly regarded approach in academic discussions. It acknowledges that environmental, social, and economic factors within a watershed are intricately linked. Land use impacts water quality, economic activities affect social justice, and environmental health influences livelihoods. The IWM avoids treating these factors in isolation. This holistic approach fosters sustainable solutions that consider all aspects of the watershed, balancing environmental protection with economic development and social well-being. Furthermore, IWM allows flexible solutions that can adapt to changing circumstances, making it a valuable tool for effective WDM according to the findings of this study.

-

Invest in capacity building: The government and development partners should invest in capacity-building programs to enhance the skills and knowledge of stakeholders involved in WDM. Capacity building is a cornerstone concept in academic discussions on WDM. Equipping stakeholders with the necessary skills and knowledge is crucial. Training programs on various WDMPs, monitoring techniques on watershed resources, and project management empower participants to be more effective. This translates to improved decision-making as stakeholders gain the ability to analyse complex issues and data. Furthermore, capacity building fosters long-term sustainability by equipping stakeholders with the skills to manage and maintain watershed projects. This study highlights that investing in human resources strengthens not only individual capabilities but also the overall capacity for effective and sustainable WDM.

-

Improving monitoring and evaluation: The government should establish a robust monitoring and evaluation system to track the effectiveness of WDM interventions and inform policy decisions. Robust monitoring and evaluation systems are championed for WDM. They provide the data needed for evidence-based decision-making. By tracking the effectiveness of interventions, policymakers can see what works and adapt future strategies accordingly. Monitoring and evaluation also allows for early identification of challenges, enabling course correction before problems become entrenched. Furthermore, it fosters accountability by tracking progress towards goals and ensuring that resources are used effectively. Monitoring environmental indicators allows for the assessment of long-term sustainability, a crucial aspect of successful WDM. This study confirms the importance of well-designed monitoring and evaluation systems. These systems ensure that interventions achieve their goals and pave the way for ongoing improvements in WDM strategies.

-

Strengthening legal frameworks: The government should review existing legal frameworks and develop new ones that promote sustainable WDMPs. Robust legal frameworks establish clear guidelines for water use, pollution control, and land management practices, reducing uncertainty and promoting responsible behaviour. Enforcement mechanisms such as permits and penalties deter unsustainable practices and ensure compliance with regulations. Furthermore, clear legal frameworks regarding water rights and responsibilities encourage practices that conserve and protect watersheds, promoting long-term sustainability. By ensuring equitable water distribution and preventing conflicts between stakeholders, a well-crafted legal framework fosters fairness within the watershed. This research highlights the importance of reviewing existing laws and developing new ones to create a strong legal foundation for sustainable WDM.

In general, by implementing these recommendations, developing countries such as Ethiopia could enhance the effectiveness of watershed management interventions and promote sustainable development in rural areas.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data will be made available upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Safi A, et al. Can sustainable resource management overcome geopolitical risk? Resour Policy. 2023;87: 104270.

Lu C, Wang K. Natural resource conservation outpaces and climate change: roles of reforestation, mineral extraction, and natural resources depletion. Resour Policy. 2023;86: 104159.

Byaro M, Nkonoki J, Mafwolo G. Exploring the nexus between natural resource depletion, renewable energy use, and environmental degradation in sub-Saharan Africa. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(8):19931–45.

Abbass K, et al. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(28):42539–59.

Mekuria W, et al. The role of landscape management practices to address natural resource degradation and human vulnerability in Awash River basin, Ethiopia. Curr Res Environ Sustain. 2023;6: 100237.

Independent Evaluation Group. The natural resource degradation and vulnerability nexus. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2021.

World Bank. World development report 2019: the changing nature of work. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2018.

Baloch MA, Khan SU-D, Ulucak ZŞ. Poverty and vulnerability of environmental degradation in sub-Saharan African countries: what causes what? Struct Change Econ Dyn. 2020;54:143–9.

Bedeke SB. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation of crop producers in sub-Saharan Africa: a review on concepts, approaches and methods. Environ Dev Sustain. 2023;25(2):1017–51.

Yigezu Wendimu G. The challenges and prospects of Ethiopian agriculture. Cogent Food Agric. 2021;7(1):1923619.

Fenta AA, et al. Land susceptibility to water and wind erosion risks in the East Africa region. Sci Total Environ. 2020;703: 135016.

Taddese G. Land degradation: a challenge to Ethiopia. Environ Manag. 2001;27:815–24.

Wassie SB. Natural resource degradation tendencies in Ethiopia: a review. Environ Syst Res. 2020;9(1):1–29.

Asnake B. Land degradation and possible mitigation measures in Ethiopia: a review. J Agric Ext Rural Dev. 2024;23–9.

Godana G, Legesse B. Assessment of the socioeconomic impact of soil erosion: the case of Dire and Dugda Dawa districts, southern Ethiopia. J Trop Agric. 2022;60(1):1–12.

Mesene M. Extent and impact of land degradation and rehabilitation strategies: Ethiopian highlands. J Environ Earth Sci. 2017;7(11):22–32.

Bantider A, et al. From land degradation monitoring to landscape transformation: four decades of learning, innovation and action in Ethiopia. 2019;19.

Hurni H, et al. Land degradation and sustainable land management in the highlands of Ethiopia. 2010.

Tizale CY. The dynamics of soil degradation and incentives for optimal management in the Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Pretoria: University of Pretoria; 2007.

Gessesse B, Bewket W. Drivers and implications of land use and land cover change in the central highlands of Ethiopia: evidence from remote sensing and socio-demographic data integration. Ethiop J Soc Sci Humanit. 2014;10(2):1–23.

Abi M, et al. Enabling policy and institutional environment for scaling-up sustainable land management in Central Highlands of Ethiopia. Ethiop J Dev Res. 2021;43(1):21–50.

Wani SP, Garg KK. Watershed management concept and principles. 2009.

Lotspeich FB. Watersheds as the basic ecosystem: this conceptual framework provides a basis for a natural classification system 1. J Am Water Resour Assoc. 1980;16(4):581–6.

Knox A, Gupta S. CAPRi technical workshop on watershed management institutions: a summary paper. 2000.

Swallow BM, Johnson NL, Meinzen-Dick RS. Working with people for watershed management. No longer published by Elsevier; 2002. p. 449–55.

Mayer A, Winkler R, Fry L. Classification of watersheds into integrated social and biophysical indicators with clustering analysis. Ecol Ind. 2014;45:340–9.

Wang G, et al. Integrated watershed management: evolution, development and emerging trends. J For Res. 2016;27:967–94.

Abbaspour KC, et al. Modelling hydrology and water quality in the pre-alpine/alpine Thur watershed using SWAT. J Hydrol. 2007;333(2–4):413–30.

Kerr J. Watershed management: lessons from common property theory. Int J Commons. 2007;1(1):89–109.

France RL. Introduction to watershed development: understanding and managing the impacts of sprawl. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2006.

Wani SP, Venkateswarlu B, Sharda V. Watershed development for rainfed areas: concept, principles, and approaches. Integrated watershed management in rainfed agriculture. Balkema Book. CRC Press. 2011; 53-86.

FAO. Climate change and food security: risks and responses. Rome: FAO; 2015.

Misra AK. Climate change and challenges of water and food security. Int J Sustain Built Environ. 2014;3(1):153–65.

Wani S, et al. Community watersheds for food security and coping with impacts of climate change in rain-fed areas. 2010.

Srivastava PK, et al. Concepts and methodologies for agricultural water management. In: Agricultural water management. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. p. 1–18.

Wani S, et al. Community watersheds for improved livelihoods through consortium approach in drought prone rainfed areas. J Hydrol Res Dev. 2008;23:55–77.

Siraw Z, Adnew Degefu M, Bewket W. The role of community-based watershed development in reducing farmers’ vulnerability to climate change and variability in the northwestern highlands of Ethiopia. Local Environ. 2018;23(12):1190–206.

Hassan AA. Strategies for out-scaling participatory research approaches for sustaining agricultural research impacts. Dev Pract. 2008;18(4–5):564–75.

Perez C, Tschinkel H. Improving watershed management in developing countries: a framework for prioritising sites and practices. London: Overseas Development Institute; 2003.

UN. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. United Nations; 2016.

Gupta AK, Goyal MK, Singh S. Ecosystem restoration: towards sustainability and resilient development. Springer Nature: Singapore; 2023.

FAO. The state of food and agriculture 2018: migration, agriculture and rural development. UN; 2018.

MoALR. Integrated watershed development strategy of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Resources; 2018.

MoA. Community based participatory watershed and rangeland development: a guideline. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agriculture; 2020.

Lakew D, et al. Community based participatory watershed development: a guidelines. Part 1. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Agricultural Rural Development; 2005.

Gashaw T. The implications of watershed management for reversing land degradation in Ethiopia. Res J Agric Environ Manag. 2015;4(1):5–12.

Gobena T, et al. Watershed management intervention on land use land cover change and food security improvement among smallholder farmers in Qarsa Woreda, East Hararge zone, Ethiopia. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica Sect B Soil Plant Sci. 2024;74(1):2281922.

Fikadu G, Olika G. Impact of land use land cover change using remote sensing with integration of socio-economic data on rural livelihoods in the Nashe watershed, Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2023;9(3): e13746.

Dejene A. Integrated natural resources management to enhance food security. The case for community-based approaches in Ethiopia. Environment and natural resources. Working Paper (FAO). 2003.

Argaw T, Abi M, Abate E. The impact of watershed development and management practices on rural livelihoods: a structural equation modeling approach. Cogent Food Agric. 2023;9(1):2243107.

Siraw Z, Bewket W, AdnewDegefu M. Assessment of livelihood benefits of community-based watershed development in northwestern highlands of Ethiopia. Int J River Basin Manag. 2020;18(4):395–405.

Mekuriaw A, Amsalu T. Assessing the effectiveness of community-based watershed management practices in reversing land degradation in the Finchwuha watershed, Gojjam, Ethiopia. Int J River Basin Manag. 2023;21(4):697–709.

Moges DM, Bhat HG. Watershed degradation and management practices in north-western highland Ethiopia. Environ Monit Assess. 2020;192:1–15.

Gumma MK, et al. Assessing the impacts of watershed interventions using ground data and remote sensing: a case study in Ethiopia. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2022;19(3):1653–70.

James W. Pragmatism: a new way for some old ways of thinking. London: Longmans, Green; 1916.

Kloppenberg JT. Pragmatism: an old name for some new ways of thinking? J Am Hist. 1996;83(1):100–38.

Dewey J. What does pragmatism mean by practical? J Philos Psychol Sci Methods. 1908;5(4):85–99.

Almeder R. A definition of pragmatism. Hist Philos Q. 1986;3(1):79–87.

Rorty R. Pragmatism, relativism, and irrationalism. In: The new social theory reader. London: Routledge; 2020. p. 147–55.

Capps J. The pragmatic theory of truth. 2019.

Dewey A, Drahota A. Introduction to systematic reviews: online learning module Cochrane training. 2016.

Xiao Y, Watson M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J Plan Educ Res. 2019;39(1):93–112.

Poonia T, Singh G. Watershed management and development—a review. Agric Rev. 2004;25(2):147–51.

Worku T, Tripathi SK. Watershed management in highlands of Ethiopia: a review. Open Access Libr J. 2015;2(6):1–11.

Abebaw WA. Review on the role of integrated watershed management for rehabilitating degraded land in Ethiopia. Environment. 2019. https://doi.org/10.7176/JBAH/9-11-02.

Zhang J, et al. Analysis on common problems of the wastewater treatment industry in urban China. Chemosphere. 2022;291: 132875.

Ellis F. Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Scoones I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: a framework for analysis. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 1998.

Kumar V, Wankhede K, Gena H. Role of cooperatives in improving livelihood of farmers on sustainable basis. Am J Educ Res. 2015;3(10):1258–66.

Bingen J, Serrano A, Howard JJFP. Linking farmers to markets: different approaches to human capital development. Food Policy. 2003;28(4):405–19.

Solesbury W. Sustainable livelihoods: a case study of the evolution of DFID policy. London: Overseas Development Institute; 2003.

Chambers R, Conway G. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; 1992.

DfID, U.J.L.D. Sustainable livelihoods guidance sheets. 1999;445.

Rakodi C. A capital assets framework for analysing household livelihood strategies: implications for policy. Dev Policy Rev. 1999;17(3):315–42.

Katz EG. Social capital and natural capital: a comparative analysis of land tenure and natural resource management in Guatemala. Land Econ. 2000;76:114–32.

Ninan K, Lakshmikanthamma S. Social cost-benefit analysis of a watershed development project in Karnataka, India. Ambio. 2001;30:157–61.

Dessalegn M, Ashagrie E. Determinants of rural household livelihood diversification strategy in South Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. J Agric Econ Ext Rural Dev. 2016;4(8):548–60.

Mengistu F, Assefa E. Enhancing livelihood assets of households through watershed management intervention program: case of upper Gibe basin, Southwest Ethiopia. Environ Dev Sustain. 2020;22(8):7515–46.

Yehun TS. Impact of watershed development on livelihood of rural farm households; in case of Burie zuria district, North West Ethiopia. 2020.

Chot G, Moges A, Shewa A. Impacts of soil and water conservation practices on livelihood: the case of watershed in Gambela region, Ethiopia. Afr J Environ Sci Technol. 2019;13(6):241–52.

Mulugeta S, Krishnaiah P. Community based watershed development from sustainable livelihood perspective: a case analysis in north Gondar zone. ZENITH Int J Multidiscip Res. 2015;5(5):18–31.

Teka K, et al. Can integrated watershed management reduce soil erosion and improve livelihoods? A study from northern Ethiopia. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2020;8(3):266–76.

Chisholm N, Woldehanna T. Managing watersheds for resilient livelihoods in Ethiopia. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2012-15-en.

Scoones I. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. J Peasant Stud. 2009;36(1):171–96.

Tyler SR, IDR Centre. Communities, livelihoods and natural resources: action research and policy change in Asia. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre; 2006.

Emery M, Gutierrez-Montes I, Fernandez-Baca E. Sustainable rural development: sustainable livelihoods and the community capitals framework. London: Taylor & Francis; 2016.

MEA. Millennium ecosystem assessment. Ecosystems; 2003.

Adger WN. Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Der klimawandel: Sozialwissenschaftliche perspektiven; 2010. p. 327–45.

Dasgupta P. An inquiry into well-being and destitution. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1993.

Pretty J, Ward H. Social capital and the environment. World Dev. 2001;29(2):209–27.

World Bank. Sustainable land management: challenges, opportunities, and trade-offs. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2006.

Bhattacherjee A. Social science research: principles, methods, and practices. Tampa: University of South Florida; 2012.

Narendra BH, et al. A review on sustainability of watershed management in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2021;13(19):11125.

Nugroho HYSH, et al. Toward water, energy, and food security in rural Indonesia: a review. Water. 2022;14(10):1645.

Descheemaeker K, et al. Effects of integrated watershed management on livestock water productivity in water scarce areas in Ethiopia. Phys Chem Earth Parts A/B/C. 2010;35(13–14):723–9.

Mengistu F, Assefa E. Towards sustaining watershed management practices in Ethiopia: a synthesis of local perception, community participation, adoption and livelihoods. Environ Sci Policy. 2020;112:414–30.

Alemu B, Kidane D. The implication of integrated watershed management for rehabilitation of degraded lands: case study of Ethiopian highlands. J Agric Biodivers Res. 2014;3(6):78–90.

Carswell G. Agricultural intensification and rural sustainable livelihoods: a think piece. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies Brighton; 1997.

Romer PM. Human capital and growth: theory and evidence. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge; 1989.

Bernstein H. Modernization theory and the sociological study of development. J Dev Stud. 1971;7(2):141–60.

Sen A. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999.

Becker GS, Murphy KM. A theory of rational addiction. J Polit Econ. 1988;96(4):675–700.

Stevens RD, Jabara CL. Agricultural development principles: economic theory and empirical evidence. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1988.

Aredo D. Agricultural development: theory, policy, and practice. 2011.

Turton C. Enhancing livelihoods through participatory watershed development in India. London: Overseas Development Institute London; 2000.

Fisher M, Chaudhury M, McCusker B. Do forests help rural households adapt to climate variability? Evidence from southern Malawi. World Dev. 2010;38(9):1241–50.

Mondal B, Loganandhan N. Employment generation potential of watershed development programmes in semi-arid tropics of India. Afr J Agric. 2013;8(23):2948–55.

Dile YT, et al. The role of water harvesting to achieve sustainable agricultural intensification and resilience against water related shocks in sub-Saharan Africa. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2013;181:69–79.

Kohun PJ, Waramboi JG. Integrating crops with livestock to maximise output of smallholder farming systems. Food Secur P N G. 2001;11:656.

Ratna Reddy V, et al. Participatory watershed development in India: can it sustain rural livelihoods? Dev Change. 2004;35(2):297–326.

Adimassu Z, Langan S, Barron J. Highlights of soil and water conservation investments in four regions of Ethiopia, vol. 182. Colombo: International Water Management Institute (IWMI); 2018.

Tilahun G, Bantider A, Yayeh D. Impact of adoption of climate-smart agriculture on food security in the tropical moist montane ecosystem: the case of Geshy watershed, Southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2023;9(12): e22620.

Palanisami K, Kumar DS. Impacts of watershed development programmes: experiences and evidences from Tamil Nadu. Agric Econ Res Rev. 2009;22:387–96.

Kerr J. Watershed development, environmental services, and poverty alleviation in India. World Dev. 2002;30(8):1387–400.

Hope R. Evaluating social impacts of watershed development in India. World Dev. 2007;35(8):1436–49.

Hassan M, et al. A review of watershed management in Bangladesh: options, challenges and legal framework. J Mater Environ Sci. 2024;15(2):225, 241.

Ibrahim AZ, et al. Examining the livelihood assets and sustainable livelihoods among the vulnerability groups in Malaysia. Indian-Pac J Account. 2017;1(3):52–63.

Surya B, et al. Natural resource conservation based on community economic empowerment: perspectives on watershed management and slum settlements in Makassar City, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Land. 2020;9(4):104.

Herrera D, et al. Upstream watershed condition predicts rural children’s health across 35 developing countries. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):811.

Norton A, et al. Harnessing employment-based social assistance programmes to scale up nature-based climate action. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2020;375(1794):20190127.

Adeniran A, Daniell KA, Pittock J. Water infrastructure development in Nigeria: trend, size, and purpose. Water. 2021;13(17):2416.

Mello I, et al. Sustainable land management with conservation agriculture for rainfed production: the case of Paraná III watershed (Itaipu dam) in Brazil. Rainfed systems intensification and scaling of water and soil management: four case studies of development in family farming; 2023. p. 99–126.

Bremer LL, et al. Who are we measuring and modeling for? Supporting multilevel decision-making in watershed management. Water Resour Res. 2020;56(1): e2019WR026011.

Ferraro PJ. Regional review of payments for watershed services: sub-Saharan Africa. J Sustain For. 2009;28(3–5):525–50.

Tesfaye A, et al. Assessing the costs and benefits of improved land management practices in three watershed areas in Ethiopia. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2016;4(1):20–9.

Gebregziabher G, et al. An assessment of integrated watershed management in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: International Water Management Institute (IWMI); 2016.

Tansey G, Worsley A. The food system. London: Routledge; 2014.

Maxwell S, Frankenberger T. Household food security: concepts, indicators, measurements. A Technical; 1992.

Wani SP, Sudi R, Pathak P. Sustainable groundwater development through integrated watershed management for food security. Bhu-Jal News Q J. 2009;24(4):38–52.

Degefa T. Household seasonal food insecurity in Oromiya zone: causes. organization for social science research in eastern and southern Africa (OSSREA) research report. 2002(26).

Limaye SD. Watershed management for sustainable water supply and food security. International journal of hydrology. 2019; 3(1):1. DOI: 10.15406/ijh.2019.03.00153