Abstract

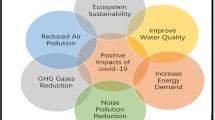

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a worldwide lockdown, and this restriction on human movements and activities has significantly affected society and the environment. Some effects might be quantitative, but some might be qualitative, and some effects could prolong immediately and/or persistently. This study examined the consequences of global lockdown for human movement and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions using an air pollution index and dataset and satellite image analyses. We also evaluated the immediate (during lockdown) and persistent (after lockdown) effects of lockdown on achieving the SDGs. Our analysis revealed a drastic reduction in human movement and NO2 emissions and showed that many SDGs were influenced both immediately and persistently due to the global lockdown. We observed the immediate negative impacts on four goals and positive impacts on five goals, especially those concerning economic issues and ecosystem conservation, respectively. The persistent effects of lockdown were likely to be predominantly reversed from their immediate impacts due to economic recovery. The global lockdown has influenced the global community’s ability to meet the SDGs, and our analysis provides powerful insights into the status of the internationally agreed-upon SDGs both during and after the COVID-19-induced global lockdown.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Society changed drastically in 2020 due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. COVID-19 was first observed in Wuhan, China, and had spread to every continent by April 2020 [1, 2]. To reduce the spread of COVID-19, China imposed a lockdown in Wuhan City on 23 January 2020 [1]. WHO reported 202,138,110 infected cases, with 4,285,299 confirmed deaths in 215 countries and territories around the world resulting from COVID-19 up to 8 August 2021 (URL: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-operational-update-on-covid-19---9-august-2021). The disease has caused a massive global health challenge and created ripples in the medical fraternity [1, 2]. Undoubtedly, unprecedented strategies are required, such as the massive surveillance to prevent spreading and the creation of a sophisticated network of diagnostics and medical facilities for immediate detection and treatment of the disease.

A major implication of the pandemic were ‘lockdowns’ both at the global and local scales since by April 2020, people in many countries were under strict movement restrictions [1]. Besides restricting movement, lockdowns also affected educational, political, and economic activities [3], with the resulting consequences expected to significantly impact both society and the environment [4,5,6,7]. Significant effects of the lockdown have already been observed on the global economy [8], air pollution [9,10,11], and wildlife conservation [5]. Here, multiple levels of lockdown policies [12] are considered that restrict society and behaviour. Also, the significant effects were recovered after reducing the lockdown, especially economic recovery occurred in both lower-middle-income countries and high-income countries [5].

However, the effects of various global lockdown restrictions on society and the environment have not been sufficiently evaluated and synthesised as we introduced above, especially the resulting environmental footprint. Herein, we summarise the consequences of the global lockdown on society and the environment using air pollution and human movement indices, particularly focusing on the environmental footprint. Using case studies and predictions related to the COVID-19-induced global lockdown, we evaluate and debate the impacts of the global lockdown on current and future sustainable development comprehensively.

The roadmap with goals and indicators for the sustainable development of human society was established by the United Nations as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [13]. The SDGs set an agenda for 2030 to transform the world by simultaneously ensuring human well-being, economic prosperity, and environmental conservation [13]. The SDGs serve as milestones to pave the way for sustainable development for both developing and developed countries. The SDGs, comprising 17 goals and 169 targets, address the challenges faced by humanity. With their corresponding targets, they expand upon various aspects of sustainable development, including societal structure, economy, policy, and sustainable ecosystem use [13, 14]. Some studies have suggested that COVID-19 can affect SDG achievements [4, 6, 7], but these studies have not evaluated the effect of the pandemic on all SDG targets. We focus on all SDG achievement as a proxy to evaluate global lockdown impacts on current and future sustainable development. Although that approach is qualitative, we could evaluate the effects of global lockdown impacts comprehensively. Current global responses to the COVID-19 crisis are likely to impact the ability to deliver all SDGs within the intended timescales thereby leading to uncertainties [15].

We first analysed how pandemic influenced the various quantitative factors, including the national lockdown policy, human movement, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions using an air pollution index based on database and satellite images from ‘before lockdown’ to ‘during lockdown’. Then, we presented how the global lockdown due to COVID-19 in early 2020 either enabled or inhibited the achievement of the SDGs either immediately or persistently (Fig. 1). Next, we analysed how the global lockdown influenced SDG achievements using our data and synthesised literature. We also assessed the immediate (during lockdown) and persistent (after lockdown) achievements for each SDG target using a simple assessment score employed in a previous study [16]. Finally, we have discussed the current and future influences of the global lockdown on society and the environment using the SDG scores and predict its persistent effects on SDG achievements.

Conceptual illustration of the COVID-19 pandemic effect on SDG achievements through global lockdown consequences of societal changes. The COVID-19 GRSI is used as the lockdown degree index for each country on 15 June 2020. Illustrations are adopted from Irasutoya (https://www.irasutoya.com), except for SDG icons and the figure. SDG icons are adopted from https://www.globalgoals.org/resources

2 Materials and methods

2.1 COVID-19 Government Response Stringency Index (GRSI)

We used data on the government responses to COVID-19, published by the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) [17]. OxCGRT collected COVID-19 GRSI daily from publicly available information for indicators, including ‘school closures’, ‘workplace closures’, ‘cancel public events’, ‘restrictions on gatherings’, ‘close public transport’, ‘public information campaigns’, ‘stay at home’, ‘restrictions on internal movement’, and ‘international travel controls’. The COVID-19 GRSI is a simple additive score of these nine indicators based on an ordinal scale from 0 to 100. The full details can be found at https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-stringency-index.

We mapped the country-level COVID-19 GRSI data from 1 March 2020 to 1 June 2020 (Additional file 1: Fig. S1).

2.2 Human migration

We used the data from the global mobility report published by Google (https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/) to observe daily changes in human migration. This dataset describes changes in movements from the baseline, the median value of the five weeks from 3 January 2020 to 6 February 2020 (https://support.google.com/covid19-mobility/answer/9824897?hl=en&ref_topic=9822927). The mobility changes are classified into six categories: retail and recreation, grocery and pharmacy, parks, transit stations, workplaces, and residential. The data did not include any personally identifiable information, such as an individual’s location, contacts, or movement. Thus, the change values were built from aggregated and anonymised datasets of users who left their location history setting on for Google services, which is off by default. We used country-level mobility data for the six categories, collected from 15 February 2020 to 1 June 2020.

2.3 NO2 emissions

We used satellite-based NO2 data observed by the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) onboard the Sentinel-5 Precursor launched by the European Space Agency with a spatial resolution of 0.01° as a proxy for air pollution data [18]. The data are available from July 2018 in the Google Earth Engine environment (https://earthengine.google.com), a planetary-scale cloud computing system for satellite imagery and geospatial datasets. To obtain NO2 data worldwide and visualise changes in NO2 emissions in response to the lockdown policies (e.g. from March 2020 to May 2020), the monthly median of the total vertical column of NO2 (the ratio of the NO2 slant column density and the total air mass factor) was calculated for every 0.01° grid in April 2019 and April 2020. Subsequently, we spatially aggregated NO2 emissions in each country and mapped the change rate ((NO2_2020 – NO2_2019)/NO2_2019) for each country.

2.4 Selecting SDG targets

The 17 SDGs are said to be ‘transforming our world’ and are a part of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [13]. The SDGs are associated with 169 targets, where each goal has 5 to 19 targets. We reviewed all 169 targets and selected those potentially influenced by the global lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The selection criteria were (1) the target could be influenced by human activities, including migration either directly or indirectly, and (2) we could evaluate the relationship between the accomplishment of targets and lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, we avoided targets that were conceptual, aimed to establish a social regulatory role, and aimed to get a social right. Consequently, we selected a total of 76 targets, of 17 which covered all goals.

2.5 Scoring procedure to evaluate the effects of the lockdown

Lockdown policies have multiple levels [12]. We included all lockdown phenomena and policies that restricted society and behaviour in the scoring. We used a simple scoring system to evaluate the global lockdown effects on the achievement of each goal, and we calculated the conflict-synergy scores following the method used by Ibisch et al. [16].

The target score calculations were based on a simple index, where ‘negative’ indicated a negative influence, ‘positive’ indicated a positive influence, and ‘undecided’ indicated no influence or debating the pros and cons. On ‘undecided’, it has difficulty to discuss about that so we treat that as pending issue. The scores in each target could describe as:

-

− 1 (indicated by blue bar in Fig. 5): the lockdown negatively influence for the accomplishment on the target,

-

1 (indicated by red bar in Fig. 5): the lockdown positively influence for the accomplishment on the target,

-

0 (indicated by grey bar in Fig. 5): pending issue currently on the relationships with lockdown and the target.

In addition, we scored these indices according to two timescales: (1) immediate influence and (2) persistent influence. The scores of each SDG are based on a simple index comprising individual scores attributed to the corresponding targets.

We basically defined the score of each target that the literature review (including preprints and public reports) showed to be influenced by the lockdown. We could not conduct systematic literature survey because there were too many literatures on that topic (nature news, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03564-y), and uncertainty regarding some effects remained [19]. Thus, we used descriptions to determine the target effects, and we did not use any specific cases. Some of the targets were clearly influenced by the lockdown. For example, Target 3 b, which aims to support vaccines and medicines for developing countries, can be directly influenced by COVID-19 issues including lockdown. In such cases, we attributed a score, even without consulting the literature. The literature survey was conducted during September 2020, and an additional survey to find the literature that could not be found the first time was conducted in both June and October 2021. This approach was found to be effective in all cases (Additional file 2: Table S1).

3 Results

3.1 Global lockdown and its consequences

We analysed the lockdown policies, human movements, and NO2 emissions globally from February 2020 to June 2020. We exhibit the COVID-19 GRSI as a government policy response to COVID-19 [17] in Fig. 2. The COVID-19 GRSI scores were calculated daily based on citizen restriction policies. We found a higher GRSI score spread from China and its surrounding countries and increased from February 2020 to May 2020 (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Fig. S1). In Asian countries, the GRSI decreased in May 2020, while other countries maintained high GRSI values during this period.

We illustrated global mobility changes to observe daily changes in human migration through Google services (Fig. 3 for the ‘workplaces’ and ‘residential’ categories). The ‘Workplace’ category was altered by − 80% in the measured countries, while the ‘residential’ category increased. The other mobility categories, including ‘retail and recreation’, ‘grocery and pharmacy’, ‘parks’, and ‘transit stations’, are displayed in Additional file 1: Fig. S2, and they also drastically decreased compared to the baseline after the global lockdown.

We calculated the change rate between the monthly median NO2 emission values for April 2019 and April 2020 for every country, and these are mapped in Fig. 4. We found that most countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, and North and South America exhibited negative change rates between 2019 and 2020. However, countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa exhibited higher change rates than those in other regions.

3.2 SDG achievement scoring

Using a simple scoring method, we summarised the positive, negative, and neutral effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on SDG achievements. We displayed the scoring of each goal (Table 1, Fig. 5) for the 73 targets (Fig. 5a). We found mixed negative and positive scores for SDG achievements when considering the immediate effects of the global lockdown (Fig. 5b). We observed many negative SDG target scores (Fig. 5b), such as those for SDGs 2 (zero hunger), 8 (decent work and economic growth), 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure), and 17 (partnerships). These mainly negatively affected SDGs concerned with food, economic, and industrial issues. Thus, these goals conflicted with the global lockdown. By contrast, SDGs 3 (good health and well-being), 6 (clean water and sanitation), 11 (sustainable cities and communities), 12 (responsible consumption and production), and 15 (life on land) exhibited more positive scores than the other Goals. These goals primarily concerned human health and environmental issues, including ecosystem conservation.

When considering the persistent effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on SDG achievements, Goal 6 exhibited the same score as that of the immediate effect (Fig. 5b). The other SDGs exhibited different achievements compared with their immediate responses (Fig. 5b and c). In particular, the scores of SDGs 11, 13 (Climate action), and 15 mostly shifted from positive to negative, which may be due to the recovery of human activities, including the economy. By contrast, SDGs 9 and 10 (reduced inequalities), 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions), and 17 predominantly changed from negative to positive, which may be due to improved governance. The detailed responses for each target were displayed in Additional file 2: Table S1. Several SDG targets showed ambivalent (instead of synergistic) effects of the global lockdown.

4 Discussion

We evaluated the effects of the global lockdown on society and the environment. We found drastic changes in government policies in response to COVID-19, such as increasing expenditures, reducing human movement, reducing human mobility/working style, and consequently reducing air pollution, as evidenced by NO2 data. The reduction in air pollution may result from the reduction in economic and transportation activities [9, 19,20,21]. For example, the absence of motor vehicle traffic and suspended manufacturing during the COVID-19 pandemic in China led to a ~ 90% reduction in NO2 emissions countrywide [22]. The global economy drastically slowed due to the COVID-19 pandemic [23]. As the changes in NO2 emissions are consistent with those in other emissions such as carbon dioxide (CO2), ozone (O3), and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) [20, 24, 25], the NO2 emission level can be regarded as an air pollution indicator. Thus, we found the degree of reduction in air pollution response to the lockdown as a proxy through the NO2 observation. Most countries in the world reduced air pollution through their lockdown policies (Fig. 2b).

These changes began in early March 2020 after COVID-19 spread globally. Such global changes in society due to a global lockdown have not been observed previously due to limited observation techniques. In this study, we originally examined the global lockdown consequences for human movement and environmental impacts using current technologies, such as human location big data via smartphone and satellite images. Global consequences of the lockdown have been observed for other phenomena, such as CO2 emissions [9], air PM2.5 concentration [26], human mobility via ‘Disease Prevention Maps’ by Facebook users [27], and environmental noise [28]. Against these previous works, we here provided new consequences of the global lockdown using new scoring and data of NO2 emissions, with results similar to those of previous reports.

The COVID-19-induced lockdown may negatively affect the achievement of the SDGs concerning food, the economy, and infrastructure (e.g. Goals 3 and 9). The lockdown is expected to substantially influence the food supply chain [29], infrastructure, and the economy [23] due to restricted human movement, food production, and economic activities. The global lockdown may accelerate the achievements of certain SDGs, especially those focused on improving human health and conserving ecosystems. Especially for food security, some studies have assessed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security and resulting health effects [30,31,32]. Galanakis [33] surmised that the COVID-19 pandemic had created a new era for food-supply chains. We will have to face many significant challenges, e.g., ensuring food safety and security, reducing losses and food wastage, as well as identifying alternative, safe protein sources that meet the nutritional expectations of consumers.

The global lockdown may reduce global climate change impact due to the relative decline in air pollution (Goal 13) [9, 26], conserve sustainable cities [11], and protect life on land [15] through a lower human impact on ecosystems [5]. Consequently, human health may improve, excluding those who contract COVID-19 (Additional file 2: Table S1). These improvements are primarily due to restricted human movements and economic activities, which reduce air pollution. Certain scholars expected reduced human mobility and activity during the global lockdown to significantly impact ecosystems because reducing the human impact on the environment allows ecosystems to recover and conserves species [4, 34].

Regarding persistent effects on SDG achievements up to 2030, the SDG scores changed drastically from the immediate ones. The achievements of climate change and ecosystem protection, such as Goals 11, 13, and 15, predominantly shifted from positive to negative, while those of economic issues, such as Goals 9, 10, and 16, primarily exhibited a negative to positive trend. This occurred primarily because economic recovery that goes against ecosystem protection can be expected to occur after the global lockdown. Forster et al. [35] simulated the increase in global temperature after the economic recovery up to 2030. Therefore, global economic recovery could substantially affect the persistent achievements of the SDGs concerning ecosystem protection and climate change mitigation. Furthermore, there were conflicting effects among goals protecting biodiversity and those promoting economic development [16, 36]. Therefore, a comprehensive debate is necessary to consider the achievements of SDGs concerning economic recovery and ecosystem management after global lockdown.

There is a growing body of scientific information on how to achieve SDGs [16, 37,38,39], and the impacts of the global lockdown have been well evaluated using the current global policy framework. Moreover, major global lockdown policies and the subsequent economic recovery, such as the cohesion policy of developed countries, may not consider the future SDG achievements for 2030. Therefore, policies concerning SDGs should be considered while factoring in the global lockdown and subsequent economic recovery.

This study design and the perspectives have certain limitations. Our simple score analysis for SDG achievements represents findings in the literature on how the global lockdown affects the SDGs. Although we carefully considered the scores, certain scores may have been overlooked or underestimated. In addition, we should assume that new evidence of the global lockdown effects on SDGs will be published in the future. Considering these limitations, the scoring estimates have various uncertainties. Therefore, we recommend studying the reality of SDG achievement in the future by directly measuring the SDGs, human movement, and air pollution. We scored the SDG achievement at the global scale by limiting the data; however, developing countries are more severely influenced by the global lockdown due to their limited governmental budgets [40]. Therefore, we encourage the assessment of SDG achievements at the country or regional level.

Recently, with increasing levels of COVID-19 vaccination, the lockdown has been reduced in parts of the world. The changing lockdown situation could improve or reduce the SDG achievements at the country scale as well as the global scale. Moreover, use of resources for the COVID-19 pandemic, e.g., lockdown, is likely to hinder reactions to concurrent threats (e.g., heat waves, wildfires, drought, and extreme weather) as under-resourced systems and emergency responses become stretched and disrupted [41], radically transforming the current state of global development [42]. Such threats increase the potential for geopolitical unrest, and the cost of dealing with these stressors could divert funding from the existing SDG targets [6].

In conclusion, we have highlighted the changes in society, the environment, and SDG achievements due to the immediate and persistent effects of the global lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although our simple score analysis scored the SDG achievement by limiting the data and containing any uncertainly, global lockdown significantly impacted society and the environment. Also, our study is a first step to describe the time-series observation by satellite and the prediction for SDGs achievement, but time-series analysis for the air pollution [43] and the scenario analysis for prediction [44] would be helpful to further analysis and consequently policy making under the COVID-19 lockdown. Moreover, it greatly impacted the immediate achievements of the most SDGs, with mainly negative and positive effects on economic and environmental issues, respectively. In addition, we found there were persistent effects on achievements for most of the goals. We are at a critical turning point for the future of human society and the Earth, and the SDG achievement analysis provides powerful evidence for this from the SDG perspective [39]. In addition, the SDGs represent a leap forward compared to the Millennium Development Goals [45]. Humanity is currently facing the COVID-19 pandemic; however, to achieve a sustainable society shared principles and legislation among nations must be developed. The political choices made during and after the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially assist the development of a sustainable society by 2030 according to he SDG achievement as we partly predicted.

Data availability

We used the data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), the global mobility report openly published by Google (https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/), and Google Earth Engine environment (https://earthengine.google.com).

References

Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033.

World Health Organization (WHO) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): weekly epidemiological, update 1; 2020.

Lau H, Khosrawipour V, Kocbach P, Mikolajczyk A, Schubert J, Bania J, Khosrawipour T. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Travel Med. 2020;27:taaa037.

Di Marco M, Baker ML, Daszak P, De Barro P, Eskew EA, Godde CM, Harwood TD, Herrero M, Hoskins AJ, Johnson E, Karesh WB, Machalaba C, Garcia JN, Paini D, Pirzl R, Smith MS, Zambrana-Torrelio C, Ferrier S. Opinion: Sustainable development must account for pandemic risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:3888–92.

Wang Q, Zhang F. What does the China’s economic recovery after COVID-19 pandemic mean for the economic growth and energy consumption of other countries? J Clean Prod. 2021;295:126265.

Naidoo R, Fisher B. Reset sustainable development goals for a pandemic world. Nature. 2020;583:198–201.

Wenham C, Smith J, Davies SE, Feng H, Grépin KA, Harman S, Herten-Crabb A, Morgan R. Women are most affected by pandemics—lessons from past outbreaks. Nature. 2020;583:194–8.

Naisbitt B, Boshoff J, Holland D, Hurst I, Kara A, Liadze I, Macchiarelli C, Mao X, Juanino PS, Thamotheram C, Whyte K. The World Economy: Global outlook overview. Nat Inst Econ Rev. 2020;252:F44–88.

Liu Z, Ciais P, Deng Z, Lei R, Davis SJ, Feng S, Zheng B, Cui D, Dou X, Zhu B, Guo R, Ke P, Sun T, Lu C, He P, Wang Y, Yue X, Wang Y, Lei Y, Zhou H, Cai Z, Wu Y, Guo R, Han T, Xue J, Boucher O, Boucher E, Chevallier F, Tanaka K, Wei Y, Zhong H, Kang C, Zhang N, Chen B, Xi F, Liu M, Bréon FM, Lu Y, Zhang Q, Guan D, Gong P, Kammen DM, He K, Schellnhuber HJ. Near-real-time monitoring of global CO2 emissions reveals the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5172.

Otmani A, Benchrif A, Tahri M, Bounakhla M, Chakir EM, El Bouch M, Krombi M. Impact of Covid-19 lockdown on PM10, SO2 and NO2 concentrations in Salé City (Morocco). Sci Total Environ. 2020;735:139541.

Sicard P, De Marco A, Agathokleous E, Feng Z, Xu X, Paoletti E, Rodriguez JJD, Calatayud V. Amplified ozone pollution in cities during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sci Total Environ. 2020;735:139542.

Alvarez FE, Argente D, Lippi F. A simple planning problem for COVID-19 lockdown (No. w26981). Natl Bureau Econ Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26981.

United Nations (UN). Bureau of the Committee of Experts on Environmental Economic Accounting. System of Environmental-Economic Accounting 2012: Central Framework. United Nations Publications; 2014.

UN General Assembly. A/RES/70/1 Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution. 2015;25:1–35.

Fenner R, Cernev T. The implications of the Covid-19 pandemic for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals. Futures. 2021;128:102726.

Ibisch PL, Hoffmann MT, Kreft S, Pe’er G, Kati V, Biber-Freudenberger L, DellaSala DA, Vale MM, Hobson PR, Selva N. A global map of roadless areas and their conservation status. Science. 2016;354:1423–7.

Hale T, Angrist N, Goldszmidt R, Kira B, Petherick A, Phillips T, Webster S, Cameron-Blake E, Hallas L, Majumdar S, Tatlow H. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:529–538.

Veefkind JP, Aben I, McMullan K, Förster H, de Vries J, Otter G, Claas J, Eskes HJ, de Haan JF, Kleipool Q, van Weele M, Hasekamp O, Hoogeveen R, Landgraf J, Snel R, Tol P, Ingmann P, Voors R, Kruizinga B, Vink R, Visser H, Levelt PF. TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: a GMES mission for global observations of the atmospheric composition for climate, air quality and ozone layer applications. Remote Sens Environ. 2012;120:70–83.

Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, Agha R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–93.

Corpus-Mendoza AN, Ruiz-Segoviano HS, Rodríguez-Contreras SF, Yañez-Dávila D, Hernández-Granados A. Decrease of mobility, electricity demand, and NO2 emissions on COVID-19 times and their feedback on prevention measures. Sci Total Environ. 2021;760:143382.

Venter ZS, Aunan K, Chowdhury S, Lelieveld J. COVID-19 lockdowns cause global air pollution declines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(32):18984–90.

Le T, Wang Y, Liu L, Yang J, Yung YL, Li G, Seinfeld JH. Unexpected air pollution with marked emission reductions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020;369:702–6.

Fernandes N. Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy. 2020 Available at SSRN 3557504.

Liu Z, Ciais P, Deng Z, Lei R, Davis SJ, Feng S, Zheng B, Cui D, Dou X, Zhu B, Guo R, Ke P, Sun T, Lu C, He P, Wang Y, Yue X, Wang Y, Lei Y, Zhou H, Cai Z, Wu Y, Guo R, Han T, Xue J, Boucher O, Boucher E, Chevallier F, Tanaka K, Wei Y, Zhong H, Kang C, Zhang N, Chen B, Xi F, Liu M, Bréon FM, Lu Y, Zhang Q, Guan D, Gong P, Kammen DM, He K, Schellnhuber HJ. Near-real-time monitoring of global CO 2 emissions reveals the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5172.

Goldberg DL, Anenberg SC, Griffin D, McLinden CA, Lu Z, Streets DG. Disentangling the impact of the COVID‐19 lockdowns on urban NO2 from natural variability. Geophys Res Lett. 2020;47(17):e2020GL089269.

Chen F, Wang M, Pu Z. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on global air quality and health. Sci Total Environ. 2020;753:142533.

Bonaccorsi G, Pierri F, Cinelli M, Flori A, Galeazzi A, Porcelli F, Schmidt AL, Valensise CM, Scala A, Quattrociocchi W, Pammolli F. Economic and social consequences of human mobility restrictions under COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:15530–5.

Lecocq T, Hicks SP, Van Noten K, van Wijk K, Koelemeijer P, De Plaen RSM, Massin F, Hillers G, Anthony RE, Apoloner MT, Arroyo-Solórzano M, Assink JD, Büyükakpınar P, Cannata A, Cannavo F, Carrasco S, Caudron C, Chaves EJ, Cornwell DG, Craig D, den Ouden OFC, Diaz J, Donner S, Evangelidis CP, Evers L, Fauville B, Fernandez GA, Giannopoulos D, Gibbons SJ, Girona T, Grecu B, Grunberg M, Hetényi G, Horleston A, Inza A, Irving JCE, Jamalreyhani M, Kafka A, Koymans MR, Labedz CR, Larose E, Lindsey NJ, McKinnon M, Megies T, Miller MS, Minarik W, Moresi L, Márquez-Ramírez VH, Möllhoff M, Nesbitt IM, Niyogi S, Ojeda J, Oth A, Proud S, Pulli J, Retailleau L, Rintamäki AE, Satriano C, Savage MK, Shani-Kadmiel S, Sleeman R, Sokos E, Stammler K, Stott AE, Subedi S, Sørensen MB, Taira T, Tapia M, Turhan F, van der Pluijm B, Vanstone M, Vergne J, Vuorinen TAT, Warren T, Wassermann J, Xiao H. Global quieting of high-frequency seismic noise due to COVID-19 pandemic lockdown measures. Science. 2020;369:1338–43.

Laborde D, Martin W, Swinnen J, Vos R. COVID-19 risks to global food security. Science. 2020;369:500–2.

Akter S. The impact of COVID-19 related ‘stay-at-home’ restrictions on food prices in Europe: findings from a preliminary analysis. Food Secur. 2020;12(4):719–25.

Amjath-Babu TS, Krupnik TJ, Thilsted SH, McDonald AJ. Key indicators for monitoring food system disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: insights from Bangladesh towards effective response. Food Secur. 2020;12(4):761–8.

Pakravan-Charvadeh MR, Mohammadi-Nasrabadi F, Gholamrezai S, Vatanparast H, Flora C, Nabavi-Pelesaraei A. The short-term effects of COVID-19 outbreak on dietary diversity and food security status of Iranian households (A case study in Tehran province). J Clean Prod. 2021;281:124537.

Galanakis CM. The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods. 2020;9(4):523.

Rutz C, Loretto MC, Bates AE, Davidson SC, Duarte CM, Jetz W, Johnson M, Kato A, Kays R, Mueller T, Primack RB, Ropert-Coudert Y, Tucker MA, Wikelski M, Cagnacci F. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nat Ecol Evol. 2020;4:1156–9.

Forster PM, Forster HI, Evans MJ, Gidden MJ, Jones CD, Keller CA, Lamboll RD, Quéré CL, Rogelj J, Rosen D, Schleussner CF, Richardson TB, Smith CJ, Turnock ST. Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19. Nat Clim Chang. 2020;10:1–7.

Mazor T, Doropoulos C, Schwarzmueller F, Gladish DW, Kumaran N, Merkel K, Di Marco M, Gagic V. Global mismatch of policy and research on drivers of biodiversity loss. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2:1071–4.

Vinuesa R, Azizpour H, Leite I, Balaam M, Dignum V, Domisch S, Felländer A, Langhans SD, Tegmark M, Fuso NF. The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat Comm. 2020;11:233.

Nerini FF, Sovacool B, Hughes N, Cozzi L, Cosgrave E, Howells M, Tavoni M, Tomei J, Zerriffi H, Milligan B. Connecting climate action with other sustainable development goals. Nat Sustain. 2019;2:674–80.

Nilsson M, Chisholm E, Griggs D, Howden-Chapman P, McCollum D, Messerli P, Neumann B, Stevance AS, Visbeck M, Stafford-Smith M. Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain Sci. 2018;13:1489–503.

Barbier EB, Burgess JC. Sustainability and development after COVID-19. World Dev. 2020;135:05082.

Islam MS, Potenza MN, van Os J. Posttraumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: upcoming challenges in Bangladesh and preventive strategies. Int J Soc Psy. 2020;67(2):205–6.

Gulseven O, Al Harmoodi F, Al Falasi M, Alshomali I. How the COVID-19 pandemic will affect the UN sustainable development goals? 2020; https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3592933.

Wang Q, Li S. Nonlinear impact of COVID-19 on pollutions–evidence from Wuhan, New York, Milan, Madrid, Bandra, London, Tokyo and Mexico City. Sustain Cities Soc. 2021;65:102629.

Wang Q, Li S, Li R, Jiang F. Underestimated impact of the COVID-19 on carbon emission reduction in developing countries–a novel assessment based on scenario analysis. Environ Res. 2022;204:111990.

United Nations Department of Public Information. Millennium Development Goals Report 2009 (Includes the 2009 Progress Chart). United Nations Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HD, TO, and NT designed the study; NT collected the spatial data; NT and TO analysed the data; HD, TO, and NT interpreted the results; and HD, TO, and NT wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doi, H., Osawa, T. & Tsutsumida, N. Assessing the potential repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on global SDG attainment. Discov Sustain 3, 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-021-00067-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-021-00067-2