Abstract

In an industry that has experienced rapid growth for a number of years, where product differentiation is minimal, the marketing tactics of online sports gambling (OSG) bookmakers are likely to push the boundaries of what can be considered responsible, as companies seek to stand out from competitors and take advantage of industry growth. This research aims to explore how the marketing tactics of OSG companies shape the gambling habits of young adult consumers, and whether this demographic considers these tactics responsible. Recommendations are made on how online bookmakers can remain responsible in their marketing to young adults. Findings revealed that the primary motivation behind young adults’ recreational gambling was the excitement induced through participation. Further, young adults’ OSG bookmaker preference is influenced by promotional offers for existing customers. Results from the study indicate that in general, young adults do not deem the varied marketing techniques employed by OSG companies as irresponsible practices. However there were concerns regarding the potential impact of the continued increase in OSG marketing on problem gamblers and children (under 18).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ‘gamblification’ of sport (McMullan 2011) has been evident for all to see. Whilst sport has always had an association with gambling, current sporting events are inundated with advertisements for a wide variety of bookmakers and opportunities to gamble, with a 600% increase in gambling advertisements following the deregulation of the sector in 2007 (Guardian 2013). Although an increase in marketing a particular product or service is not a problem in itself, it has been argued that when the product or service represents a clear public health issue (Adams et al. 2009; Korn and Schaffer 1999; Livingstone and Adams 2011; Wheeler et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2011), there is cause for concern. In an industry that has experienced such extensive growth in the past decade (Soriano et al. 2012), it seems possible that companies could choose to neglect their responsible marketing duties in an attempt to gain an advantage over competitors, in an industry where product differentiation is negligible. In addition, it seems important to determine whether OSG can be marketed more successfully than it is currently, whilst adhering to the responsible marketing duties that bookmakers are arguably bound by.

Our definition of ‘sports gambling’ is largely similar to that of Labrie and Shaffer (2011), who define sports gambling or betting as any instance of “making bets on sporting events”. However, in the context of this research, we adopt a definition of ‘sports gambling’ that is inclusive of all sports, albeit with a particular focus on football, as the majority of the demographic within our sample were engaging in and referring to sports betting on football. The terms ‘betting’ and ‘gambling’ are used interchangeably in both this paper and comparable papers, such as Lopez-Gonzalez et al. (2018a, b), who refer to ‘online sports betting’. The research presented in this paper focuses solely on online sports betting.

This paper provides an overview of the current state of knowledge surrounding OSG marketing, including current marketing techniques and gambling triggers. In addition, this research investigates how OSG is currently marketed, and which techniques appear most effective from the perspective of young, male consumers (aged 18–28 years old) at encouraging OSG initially, and subsequent repeated gambling activities. With millennials (those born between 1981 and 1996) accounting for the largest increase in online gambling of any age group worldwide in 2017 (Financial Times 2018), the need for research into this area is clear. The paper also investigates the extent to which OSG marketing techniques can be considered responsible, and suggests how marketing campaigns could be improved, while remaining responsible. This paper assesses the responsible marketing of OSG companies separate to the UK regulatory requirement of 2018 to include an explicit ‘responsible gambling’ message, or reference to ‘Be Gamble Aware’ (BeGambleAware 2020), research on which is currently available (Killick and Griffiths 2019). While the majority of research in this area concentrates on online gambling as a whole, this paper focuses on OSG specifically.

In addressing these features of the research, 3 research objectives can be outlined: (1) to examine if and how male young adults’ OSG habits are affected by gambling marketing techniques and campaigns; (2) to determine what techniques are currently being used to market OSG and whether these can be considered responsible, and (3) to consider how OSG companies can market their product both effectively and in a responsible manner. The remainder of this paper will explore the growth of OSG; gambling triggers and marketing techniques, the research method employed, followed by the results of the study and subsequent discussion. The paper draws conclusions including recommendations to OSG bookmakers and outlines directions for future research.

Literature review

Background

For an industry that only began to emerge in the mid 1990’s, online gambling is currently the fastest growing form of gambling (Soriano et al. 2012). The UK gambling industry as a whole has received increasing social acceptance (Soriano et al. 2012), and with this, a large growth in market value of roughly £6bn between 2011 and 2018 (Statista 2020). The availability and popularity of online gambling sites have also experienced a sharp increase, from an estimated 15 online betting sites in 1996 (Schwartz 2006), to now more than 2500 sites (H2 Gambling Capital 2017). These sites account for a gross yield of £5.7bn per year (Gambling Commission 2020), and comprise almost 40% of the overall market share; with the Gross Gambling Yield for online betting totalling £2.3bn which is predominantly led by football and horse betting. Such figures demonstrate the importance of having available a comprehensive body of research in this field.

There are several possible causes for the increasing popularity of OSG, the first being the increasing presence OSG receives on ‘popular media’ including television (Brown 2006), where the ‘Gambling Act’ of 2005 opened the door to a 600% rise in gambling advertisements (Ofcom 2013). The growing technological proficiency of the UK population is another factor behind the increase in online gambling popularity (Brown 2006; Ward 2005); with those aged 18–25 years having had exposure to the internet since a young age, accessing and utilising the internet has become second-nature for many young adults (Kanne et al. 2002). This, coupled with widespread internet access (Walters 2005) particularly via smart mobile phones, ensures younger generations are far less constrained in the channels through which they can gamble (James et al. 2017). The anonymity of online gambling can be regarded as an attractive feature (Brown 2006; Binde 2014) that further contributes towards the increasing popularity of OSG, as well as the growth of online blogs dedicated to internet gambling, including online social networking service ‘Twitter’, where ‘hundreds’ of accounts churn out multiple betting tips a day (Halls 2016).

It seems therefore that the creation and increasing commercialisation of the internet (Eadington 2004), coupled with its ease of access and anonymity, has provided the perfect environment for those in the gambling sector to capitalise on. Despite a fifth of 16–24 year olds spending more than 7 h a day online (The Telegraph 2018), the increased likelihood of encountering some form of OSG while surfing the web should not necessarily increase the participation of young adults in online gambling activities. Nonetheless, online gambling is experiencing a “phenomenal growth rate” (Brown 2006) amongst younger people, with university students identified as the fastest growing sector of online gamblers (Zewe 1998).

Reasons for the apparent increase in popularity of OSG amongst younger people are varied. With 36% of 18–29 year olds claiming to be constantly online (Blakemore 2015), both Derevensky et al. (2010) and Lemarié and Chebat (2017) assert that the advertisements young adults are viewing during their time online (and from other media sources) reinforce a view that gambling is a harmless leisure activity that can provide easy monetary gains. With the younger generation of today facing a ‘financial crisis’, attributed to growing student loans and unsecured borrowing (Read 2015), the prospect of monetary gains from online gambling is a likely factor in attracting this demographic to gamble. Kanne et al. (2002) argue that the increasing variety of payment methods available to young people is a further contributing factor. The range of payment methods available to young adults continues to increase, with ‘Apple Pay’ just one example of an additional deposit method recently added to online bookmaker SkyBet (SkyBet 2020).

Whilst older generations may be aware of the ‘gamblification of sport’, the youth of today are experiencing a ‘seamless assemblage’ between online gambling and various other factors, including sport, advertising, celebrity and social media (Cassidy and Ovenden 2017). This is reflected in ‘millennials’ accounting for the largest increase in online gambling of any age group worldwide in 2017 (Financial Times 2018). While research on the increasing tendency of young people to gamble online is available, this is mostly limited to the United States of America, and is focused around problem gamblers (Eadington 2004; Soriano et al. 2012; Floros 2018). It seems therefore that there is a gap in current research concerning gambling behaviour of young adults in the UK, and how their recreational gambling habits are influenced by the marketing efforts of online gambling companies.

The link between online gambling and problem gambling has received much attention in academic literature (Griffiths and Parke 2002; Soriano et al. 2012; Wood et al. 2007). The accessibility and ease of play (Griffiths et al. 2006), makes online gambling particularly attractive to those with a history of gambling addiction (Wood et al. 2007). Previous research has demonstrated a clear link between online gambling and problem gambling, with figures of between 30 and 66% of online gamblers admitting to having a gambling problem (Matthews et al. 2009; Petry 2006; Wood and Williams 2007). The ease of data capture online also creates an opportunity for online gambling retailers to take advantage of customer playing habits to target those most likely to gamble excessively (Brindley 1999), as online bookmaker ‘Betway’ have recently been accused of (BBC 2020). A rise in this ‘so-called’ irresponsible behaviour is anticipated, with online bookmakers expected to increase their focus towards targeting existing customers who have not ‘opted out’ of such data collection following the recent GDPR regulatory change in EU law (ICO 2018; Kennedy 2018).

In contrast, various authors have identified the potential positive impacts that could be achieved through online gambling retailers’ compliance with Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and responsible marketing practices. For example, Bhattacharya and Sen (2004) found increased customer loyalty for companies who were seen to be practicing CSR, this also holds true for loyalty in the online gambling arena (Griffiths et al. 2009). Therefore, it appears that the responsible provision of gambling services and its advertising has become an important part of the image of online bookmakers, with companies now beginning to recognise that demonstrating responsibility can aid the longer term sustainability of their business (Soriano et al. 2012). However, Leung and Gray (2016) maintain that there is an inverse relationship between the size of gambling firms and their level of social responsibility disclosure.

According to Soriano et al. (2012) there has been minimal research conducted into CSR and ethical marketing in so-called ‘sin industries’. Of the research conducted to date, the vast majority is limited to how marketing and CSR impacts problem gamblers, leaving a gap in research as to how responsible marketing can impact on the gambling habits and consumer trust of recreational gamblers. Furthermore, there is also an opportunity to investigate whether the results found by Griffiths et al. (2009) concerning increased consumer loyalty for Swedish gambling companies who were seen to be actively looking out for their customers’ welfare, are repeated in other countries, such as the UK.

Gambling triggers and advertising

The UK charity ‘The Mental Health Foundation’ (2020) suggests five motivations and/or triggers for gambling: the excitement and adrenaline release from gambling is a feeling that people wish to replicate; the competitive element of attempting to ‘beat the bookie’ or other players; the thrill of risk taking; attempting to solve financial problems; and escaping from stress or anxieties. Supplementary gambling triggers have also been identified to include; the glamorous and ‘high society’ image played upon by gambling companies, the idea of gambling as a social activity (Healthy Place 2020), and the desire to achieve the ‘big win’ (GamCare 2020).

Online bookmakers thus utilise various techniques to evoke these triggers and increase participation in gambling activities. The thought of gambling being a glamorous and exciting activity (Healthy Place 2020) is an image often reinforced by gambling advertisements that are promoting a sense of excitement and fantasy, achievable through participation in betting (Derevensky et al. 2010). Additionally, the brightly coloured themes, sound effects and musical overlays often found in televised gambling commercials are an attempt to stimulate betting by amplifying the excitement associated with involvement in gambling (Zangeneh et al. 2008; McMullan and Miller 2009).

In recent years, the UK and various other countries have experienced what has been described as the ‘gamblification of sport’ (McMullan 2011). During this time, both offline and online gambling companies have attempted to culturally embed gambling within sport (Dyall et al. 2009; Hing et al. 2017; Maher et al. 2006; Monaghan et al. 2008; McGee 2020). Celebrity endorsements and promotional activities that link bookmakers to sports teams have also increased (Maher et al. 2006) and many bookmakers are further cementing such links through sports team sponsorship (Remote Gambling Association 2010), with only three English Premier League football teams in the 2019/2020 season having no betting sponsorships at all (Premier League 2020).

Research suggests that it is easier to persuade a person in a positive mood to gamble (Gardner 1985), and thus humour has become a growing part of OSG companies’ marketing. Since advertising needs to capture the attention of its audience, creativity and humour serve as a platform for doing so (Binde 2009). Further, research by Heath et al. (2006) suggests that low-level cognitive processing associated with humorous adverts can help with brand reputation, since those watching are less aware of repetitive advertising, which causes critical reflection on both the frequency and content of advertisements.

Most gambling advertisements are based on the explicit or implicit message that the gambler has a chance to win (Binde 2009), thus the possibility of winning a large sum of money from a small stake is often portrayed in gambling advertisements. This technique plays on the concept of ‘Prospect Theory’ (Kahneman and Tversky 1979), which states that people are likely to either over or underestimate their chances of winning from very small probabilities; with bookmakers hoping for the former. To enhance the perception that monetary gains can be achieved through gambling, various authors (Gilovich 1983; Rosecrance 1986; Lopez-Gonzalez et al. 2018a) claim that gambling advertisements overstate the amount of skill involved in gambling, while Lopez-Gonzales et al. (2018a) concluded that themes present in recent British advertisements attempted to create a magnified idea of control in OSG. These tactics encourage the view that any potential winnings are more a result of skill than of luck. While these methods could be arguably seen as irresponsible, Shelat and Egger (2002) found that the informational content of online gambling sites and their advertisements was the single most important dimension in building trust between customers and online bookmakers, because this sort of information helped customers to better relate to the company and its policies.

Few researchers have properly examined gambling advertising and its influence on customers’ gambling behaviour (Griffiths 2005; McGee 2020; Lopez-Gonzalez et al. 2018a, b) indicate further research is needed to evaluate how gamblers perceive the metaphors present in the advertising of OSG specifically. While much of the current research regarding online gambling advertising suggests arguably deceptive techniques are most effective, there is a need to research whether OSG companies can successfully market their product in a responsible manner.

According to Binde (2009), gambling advertisements are no different to any other advertisements; their intention is to promote and sell by exaggerating the positive aspects of a product while avoiding the negative ones, using a measure of cultural and psychological insight. However, various authors have questioned whether the marketing of online gambling can be considered equivalent to the marketing of other products and services (Griffiths 2005; Soriano et al. 2012). There are proposals that the distorting of the chances of winning and costs of participating in gambling that are shown in gambling advertisements should be nullified through the provision of easily accessible information about the actual chances of winning and net costs associated with gambling (Blaszcynski et al. 2008; Eggert 2004). Monaghan and Derevensky (2008) argue that at the very least there should be the development and enforcement of responsible codes of practice and guidelines for gambling advertisements. Both proposals have arguably been acted upon to some extent through the recent UK regulatory requirement of 2018 for gambling advertisements to feature an explicit ‘responsible gambling’ message, or reference to ‘Be Gamble Aware’ (BeGambleAware 2020). Lemarié and Chebat (2017) however claim that the current efforts to nullify the pro-gambling advertisements are frequently competing unsuccessfully with advertisements that depict gambling as exciting and harmless.

Although many of the statements/imagery in gambling advertisements can be seen as a form of visual argument (Blair 1996), it is difficult to prove any of them as objectively false or deceptive. If deception is necessary for advertising, it could be argued that OSG companies must make the choice between maximising revenue and preventing the harm that Soriano et al. (2012) believe is inevitable for gambling companies. There is a need for research into whether OSG retailers must make this choice, as well as whether potential customers feel they are being deceived by gambling marketing, something Binde (2009) argues there is very little research exploring.

While literature is limited in relation to the effect of advertising on promoting healthy behaviours regarding the consumption of OSG, insight is available to draw on from other comparable fields, mostly exploring the effect of advertisements on moderating alcohol consumption. For example, studies have found that young adults who viewed advertisements that warned about the negative effects of alcohol consumption reported fewer urges to drink alcohol when compared to those who viewed alcohol promoting or non-alcohol advertisements (Strautz and Marteau 2016; Siegfried et al. 2014). Similarly, a reduction in the urge to consume alcohol was found to occur when a complete ban on alcohol advertising was implemented (Saffer and Dave 2002). It can therefore be seen that advertising messages, or complete advertising bans, have the power to influence consumption behaviours for potentially harmful products such as alcohol. While this is an important phenomenon to consider, the focus of this study was to understand the perceptions and impact that OSG advertising has on young adults, an area that is under-researched.

Method

In addressing this paper’s research objectives, qualitative, semi-structured interviews were undertaken both in-person and via telephone, with in-person interviews the preferred method of data collection. The target sample of interviewees were young adults, aged between 18 and 28 years old, with previous experience of participating in OSG; and available for interview during a specific 4-week data collection period. A purposive and opportunistic sampling approach (Easterby-Smith et al. 2015) was adopted first, which resulted in the initial recruitment of 5 participants already known to the research team, from which a snowballing recruitment technique (Pettigrew and McNulty 1995) was used to identify further participants from recommendations of those already recruited, which led to an increase of the initial sample to a total of 12 interviewees. Specifically, the resulting sample comprised 12 males (11 were university graduates), with varying levels of participation in OSG, with most claiming to take part on a weekly basis, coinciding with the majority of English Premier League football fixtures. Whilst the resultant sample was entirely male, this is not unexpected since OSG in the UK is a predominantly male pursuit, with men being six times more likely to participate than women (Wardle 2007; McGee 2020), therefore the views expressed by these male participants may not be applicable to female OSG players. An additional 13th telephone interview was conducted with a representative at one of the “Big Three” (Guardian 2016) bookmakers in the UK, which provided an important juxtaposition to the views of consumers on responsible OSG marketing.

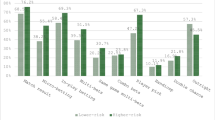

Kvale’s (1994) suggested nine types of interview questions were used as a basis for structuring the interview guide. The interview question themes, along with an indication of the corresponding research objectives that have been addressed by each interview question theme, is shown in Table 1. Respondents were reminded prior to interviewing that the research focused on OSG; and therefore their answers to all questions should focus on this specific area of gambling.

Prior to interviews being undertaken, informed consent to participate and permission to record interviews was obtained from each interviewee. All interviews undertaken were recorded, with permission from participants, and subsequently transcribed for analysis purposes. Using the transcriptions, the qualitative interview data was manually coded in line with the three research objectives outlined in Table 1, that formed the core overarching themes that provided a thematic analysis starting point, from which a number of sub-themes were identified (King 2004; Nowell et al. 2017). This approach enabled the research team to identify common and/or recurring patterns, and similarities and differences in the way interviewees discuss topics (Ryan and Bernard 2003; Braun and Clarke 2006) in the interview transcripts, which were categorised into positive and negative views within each of the interview question themes (see Table 1). During the thematic analysis of the interview transcripts, the following sub-themes were identified: gambling habits and triggers; influence of marketing on gambling habits; current marketing techniques and subsequent moral considerations; suggested ways that OSG companies can market their product effectively in a moral ethical manner. These drew particular attention to the motivations for young male adults to undertake OSG, the triggers that cause repeated gambling; and the marketing efforts that shape gambling behaviours. The results and discussion sections explore these identified themes in detail, and include the authors’ selection of the most informative and representative interviewees’ quotations that aim to support or elaborate the researchers’ interpretation (Glaser and Strauss, 1967).

Results

Gambling habits and triggers

The almost universal attraction of gambling and the most significant reason behind participants’ desire for repeated gambling, was the excitement or “thrill” (Interview12) generated through participating. For example, participants recalled how OSG had the effect of “making matches I wouldn’t otherwise care about quite exciting” (Interview2). The majority of interviewees’ gambling activities tended to focus on football matches that featured teams they had no prior interest in.

While monetary gains may initially seem to many as the primary reason for gambling (GamCare 2020), the results indicate that most respondents were not “expecting to make money” (Interview7), and that monetary gain was largely secondary to the excitement induced by placing bets online (Mental Health Foundation 2020). Results suggested that the possibility of making money was simply that, a possibility, with many candidly accepting that their gambling habits had left them in a worse financial position than if they had avoided gambling, and recognised this would “always be the case” (Interview1).

While respondents were clearly “betting to try and win” (Interview2), many interviewees spoke openly and without embarrassment about their losses. An interesting point raised in interviews was the extent to which the excitement of gambling would be sufficient to maintain the desire to gamble in the face of persistent monetary losses, indicating the strength of “excitement” as a gambling trigger (The Mental Health Foundation 2016). Regular monetary losses may “slow down” (Interview3) the frequency at which respondents gamble, however the excitement of gambling was consistently claimed as “enough” (Interview8) to maintain the desire to participate in OSG, and the main reason why interviewees continue to bet.

The vast majority of respondents interviewed gamble once a week, not staking large sums of money, around £5 a week on average, marginally higher than the UK average of £4.16 per week (The Economist 2017). These relatively small weekly bets are a contributing factor behind the excitement of gambling being sufficient to cause respondents to continue gambling in the face of monetary losses. Therefore, when interviewees were asked whether consistent monetary losses would cause them to stop gambling, the imagined loss of the small sums of money bet weekly was not deemed sufficiently undesirable to result in a complete cessation of gambling. However, an exception to this was evident from some respondents, when referring to their time at university. The sole interviewee still at university claimed that monetary gains was the “primary reason” (Interview12) motivating their participation in OSG, and they intended to cease gambling if they “stopped making money” (Interview12). This view was mirrored by another respondent when reflecting on their time at university, where the difficult “financial situation” (Interview4) encountered at the time contributed to them “betting a lot more” and being motivated exclusively by “making money”.

As the results suggest, young people who are betting small sums of money, or amounts of money that in their eyes have little significance, place far less importance on gaining money than they do on the excitement they experience from taking part in OSG. The only exception appears to come from online gamblers at university, who perhaps feel the effects of the apparent ‘financial crisis’ amongst young adults (Read 2015) worsened by university-related debt. Derevensky et al. (2010) claim that as a result of advertisements, young adults hold a view that gambling is an activity that can provide easy monetary gains, contributing to the increasing popularity of online gambling amongst young adults. However, despite our small sample, the young adults we interviewed indicated that they were “not going into it [OSG] expecting to make money” (Interview7), and that “the excitement would be enough to keep [participants] gambling” (Interview8).

The consistency at which the sample group attributed the excitement of betting as the main reason for their participation in OSG supports the findings of UK charity ‘The Mental Health Foundation’ (2020), who claim the excitement and adrenaline produced by gambling is one of its main attractions. The data from just one respondent supported the idea that solving monetary issues (The Mental Health Foundation 2020) motivated their current gambling habits, arguably prompted by this respondent being under great financial stress during their time at university.

Few other gambling triggers found in the literature were identified in this sample group. For example, there was no mention of the competitive element of gambling, using it as an escape from stress or worries, or seeking the ‘big win’ that gamblers feel is always within reach (GamCare 2020). It could be argued that the desire to gamble as a means of possibly reaching the ‘big win’ is reserved for those betting on other forms of gambling with higher payouts and longer odds, such as the National Lottery.

How marketing efforts shape gambling habits

Our results indicated two main reasons for opening an online betting account. The first and most frequently identified, is the lure of advertised promotions and bonuses, which is within the marketing powers of the online bookmakers and appeared to have the greatest influence on persuading interviewees to open new accounts. Respondents explained how they had either signed up to OSG sites “as a result of a sign up offer” (Interview4), or how they could be “enticed to move to another site if there were better promotional offers” (Interview10). This could go some way to explaining why millennials are the most likely of any age group to hold more than 5 online gambling accounts at any one time (Financial Times 2018). Results also indicated that transparency in promotional offers regarding terms and conditions is crucial if OSG bookmakers are to retain customers beyond their initial interaction. The inverse was demonstrated to be catastrophic with regards to customer loyalty; with respondents recalling that “companies I have experienced this with, I have not bet with again. It’s akin to false advertisement and as if they are tricking you” (Interview8). Given the influence that new customer promotional offers have in attracting potential gamblers to join and continue gambling with sites, this remains an under-explored area in academic literature. With the exception of Killick and Griffiths (2019) and McGee (2020) there is little mention of promotions as a marketing tactic, with most research referring to ‘glamourisation’ (Derevensky et al. 2010) or humour (Binde 2009), thus reflecting Griffiths’ (2005) claim that very few researchers have fully examined gambling advertising and its effect on customers, with a particular scarcity of qualitative research in this area (McGee 2020).

The second identified reason for registering with an OSG bookmaker was recommendations from perceived trusted sources, usually “friends” (Interview2 and Interview11). This finding may help to explain why the industry representative interviewed claimed that of a number of online bookmakers who have recently ceased trading, “virtually none of them are big named companies” (Interview13). With recommendations identified as having an influence on young adults' choice of bookmaker, this could explain the low survival rate of new entrant bookmakers. This is supported in our results, as respondents indicated the value they place in long-standing bookmakers, demonstrating the industry representative’s view that it “pays to trust an established brand” (Interview13).

While recommendations are regarded as important, our findings demonstrate that the marketing with the greatest influence on the gambling habits of young adults is that involving promotions. As well as triggering customers to sign up to websites, respondents also routinely claimed that they were actively “looking out for” (Interview4) promotional offers from OSG bookmakers which would “reward loyalty from existing customers” (Interview1). Such promotional offers, whether “free bets or loyalty rewards” (Interview9), were consistently cited as a feature attractive enough to cause respondents to either “change” (Interview3 and Interview6) their preferred bookmaker, or ensure they “keep gambling” (Interview9) with their current OSG website. While literature may theorise that advertising involving creativity or humour will capture the attention of its audience (Binde 2009), among our sample, marketing based on promotions or loyalty rewards has been identified as having the greatest influence on the gambling habits of our young adult respondents. As well as shaping the choice of OSG bookmaker that customers first gamble with, participants consistently indicated that “more campaigns and promotional offers directed towards existing customers, would encourage customers to stop switching between websites and stay with their current bookmaker” (Interview9). While excitement was cited as the main reason for gambling, no respondents explicitly stated that they were looking for a website that could offer them a more exciting experience. This suggests that the difference in the level of excitement experienced by betting across different websites is imperceptibly small; therefore customers are looking for marketing that promises the most value for money, in the shape of promotions or bonuses.

This research has identified the excitement of gambling as the primary motivation behind our sample of young male adults gambling recreationally, with the preferred OSG bookmaker of this demographic being determined by promotional offers. Whether these findings are consistent across all OSG players, is worthy of further investigation. The study also explored the extent to which young adults considered the marketing techniques currently employed by OSG bookmakers as responsible, which are addressed thematically in the following section.

Skill and ease of winning

Online bookmakers are often described as presenting gambling as an inherently skillful activity. Gilovic (1983) and Rosecrance (1986) claim that gambling advertisements will overstate the amount of skill involved in gambling, so as to persuade the customer that winning bets isn’t a result of luck, but an inevitable byproduct of their knowledge of sport. However, the vast majority of respondents did not feel OSG advertisements perpetuated an image of gambling involving a great deal of skill. The exceptions to this consensus all cited a Ladbrokes advertisement as an example (Campaign 2014). In this particular advertisement, respondents recalled how the protagonist was depicted as “clever” (Interview8) and someone who had therefore “sussed out gambling” (Interview6). The same respondents recalled how the perceived skill of the protagonist suggested “improved chances of winning” (Interview8). While this example was recalled by a number of respondents, most claimed that gambling advertisements avoided this tactic entirely, as they believed it could dissuade young people from participating in OSG if they weren’t confident in their knowledge of sport.

Respondents claimed any depiction of skill may “alienate” (Interview7) potential customers, and was therefore too risky a tactic for an industry that wanted their product to seem “accessible to anyone, not just to the customer who knows what they are doing” (Interview3). Therefore, while largely differing to the work of Gilovich (1983) and Rosecrance (1986), the fact that some respondents did identify an instance of this tactic suggests that it is not a marketing approach completely avoided by OSG bookmakers. Respondents who recalled this marketing technique raised no concerns over it being irresponsible.

According to Binde (2009) the implicit or explicit idea that the customer has a chance of winning is the central premise of almost all gambling advertisements. Findings indicate that respondents were divided over whether OSG advertisements contained such an explicit suggestion regarding chances of winning. In contrast, nearly all respondents acknowledged that they had never encountered a gambling advertisement that depicted someone losing. Respondents were in almost total agreement, in line with Binde (2009), that gambling companies “understandably” (Interview9) included the implicit message that gamblers could win, simply by not depicting gamblers losing in their advertisements. Respondents did not deem this feature of OSG marketing as irresponsible, as including an implicit message about the positive benefits of a product was a marketing tactic universal across all industries.

Excitement and glamour

Interview findings demonstrate that the excitement of OSG compels most respondents to bet repeatedly (Neighbors et al. 2002; Mental Health Foundation 2020) and the young adults that took part in this study were certainly aware of online bookmakers highlighting the excitement of gambling through their marketing campaigns (Zangeneh et al. 2008; McMullan and Miller 2009). Respondents claimed that online gambling advertisements often focused “more on the excitement” (Interview1) of betting than anything else, achieved by creating “loud, noisy advertisements” (Interview10). No concerns of irresponsibility were raised.

While closely linked to excitement, the ‘glamourisation’ of OSG was seldom mentioned by respondents. When raised, two differing views emerged. First, it was claimed that “in many ways, the glamourisation of OSG advertisements is probably less so than other products, I don’t think it’s as blatant as in other products” (Interview2); whilst an alternative respondent regarded the glamourisation portrayed as so severe it could be considered “deceptive” (Interview11) and therefore irresponsible. While the two opposing views provide an interesting insight into how young adult consumers view the glamourisation of OSG advertisements, the extent to which this tactic was noticed by respondents remains negligible, and therefore should not be considered a responsible marketing concern.

Humour and creativity

The opinions on the use of humour were largely positive, with such advertisements being sufficiently memorable that interviewees described them as “exciting” (Interview5) and “different” (Interview2). However, despite half of the respondents recalling a particular advertising campaign from UK bookmaker PaddyPower as being creative and humorous, they also believed it to be “controversial” (Interview8), or “pushing the boundaries of what is responsible” (Interview5). Thus, it would appear that for several respondents, creative or humourous marketing as referred to by Binde (2009) is effective in the eyes of consumers, however companies must be careful not to overstep the boundaries of responsible marketing so as to avoid creating “a negative impression of that company” (Interview2).

Timing and placement

The timing and placement of OSG marketing campaigns was highlighted by interviewees, despite receiving a distinct lack of attention in academic literature. Television advertisements during sporting events were cited as the most “noticeable” (Interview7) example of targeted advertising. In particular, those featured during the half-time interval of televised football matches were frequently mentioned, where it was felt “every other advertisement is for a gambling company” (Interview7). The recent addition of gambling advertisements broadcast during pre-match the player handshakes of televised football matches were also referred to specifically in the interviews, with several interviewees objecting to this. They described the timing of these advertisements as “intrusive” (Interview9); although this finding may reflect the relative newness of placing adverts at the start of a sporting event, with viewers unaccustomed to it. Several interviewees raised concerns over the increasing volume of OSG advertisements during televised sporting events. The current volume of advertising was not regarded as irresponsible (unless considering the potential impact on problem gamblers), however the general consensus was that “you couldn’t watch a game… without encountering gambling offers” (Interview3). Although some respondents acknowledged the issue that the frequency and timing of gambling advertisements during televised sports may have a negative impact on problem gamblers; and were in part averse to the broadcasting of advertisements during pre-match handshakes, the general view was that the current timing of these advertisements had largely become “expected” (Interview1), and perhaps an inevitable byproduct of the ‘gamblification of sport’ (McMullan 2011).

Any perceived increase in the volume of OSG advertising beyond its current levels was widely condemned among participants, with interviewees, particularly aware of the increasing presence of OSG advertisements on social media. One respondent claimed they “hated” (Interview2) targeted advertisements encountered on social media, as they felt their online privacy had been compromised, while another objected to ‘promotional tweets’ on social media website ‘Twitter’ (Interview6). The growth in online gambling advertising across so many different mediums was again cited as a responsible marketing issue, particularly when considering problem gamblers and children (under 18). As gambling advertising was seemingly “everywhere… on television, social media, email” (Interview3), concerns over the potential for high exposure and the resulting collateral damage to both vulnerable groups was present among participants, with one participant noting “For someone who might be recovering from a gambling addiction or is a gambling addict, you can’t watch a game of football without encountering offers.” (Interview3). Despite being raised as a responsible marketing concern among our sample group, the industry representative claimed the issue of problem gambling remained “a matter of contention” (Interview13), despite being widely accepted and regularly highlighted in literature (Griffiths and Parke 2002; Matthews et al. 2009; Soriano et al. 2012; Wood et al. 2007). While claiming to be aware of the fact that their product may be used in such a way, the industry representative argued their company held no interest in targeting problem gamblers specifically. The industry expert did however explain that in “going out of our way to try and prevent” (Interview13) problem gambling, their company ran the risk of deterring those who were “perfectly capable of regulating their own gambling” from engaging with their product. This view arguably points to a feeling of inevitability that the marketing efforts of OSG companies will invariably create some collateral damage in influencing problem gamblers, which may explain why over 90% of Twitter posts by UK online gambling companies between 2018 and 2019 contained no responsible gambling information (Killick and Griffiths 2019).

While the potential for gambling advertisements to irresponsibly influence children was raised in interviews, the level of concern varied. While one respondent claimed that as a result of this potential, gambling advertisements “should not be allowed” (Interview5), another simply deemed the impact OSG marketing had on children as “controversial” (Interview8). The industry expert acknowledged this was something online bookmakers must remain “very aware of” (Interivew13) when marketing their product, so much so that bookmakers actively targeted customers that are “an older age than we are legally entitled to” (Interview13).

While responsible marketing objections were raised when respondents empathised with gambling addicts and children, our findings suggest among our sample of young male adults, that recreational online sports gamblers are generally resigned to the fact that their contact with OSG advertisements is an inevitable part of modern life, with one respondent claiming that “if it’s not a betting advert, there will only be another advert in its place” (Interview4). Further research is needed to determine whether these views are shared by OSG players more generally.

Discussion

Consistently cited as an area respondents felt online gambling advertisements should focus on, promotional offers are an aspect of OSG marketing that, if advertised transparently, have the ability to attract customers in a fully responsible manner. Respondents expressed a desire for OSG advertisements to “be more promotions-based” (Interview1); focusing on what is often the “only reason” (Interview9) customers could be enticed to change their preferred bookmaker. While respondents were clear about the attraction of promotional offers, transparency in these offers was stressed as crucial, so as to avoid players feeling “tricked” (Interview8). The importance of being “forthright” (Interview1) and “clear” (Interview4) with the terms and conditions of promotional offers was consistently raised by the majority of respondents. This desire is perhaps influenced by interviewees' negative first experiences of OSG bookmakers that occurred after taking advantage of a promotional offer with unclear terms and conditions, which led to interviewees leaving that bookmaker in favour of another. Thus, it was perceived that greater transparency around promotions, and the conditions that must be satisfied in order to withdraw winnings, is needed. This would potentially guard against young gamblers’ negative first experiences of OSG, which have resulted in them opting to permanently gamble elsewhere.

It could be argued that promotions offering improved odds, or ‘risk free’ bets, enhance the explicit or implicit message in advertisements that the customer has a chance of winning, thus supporting the work of Binde (2009). Promotional offers have the ability to “excite” (Interview1) customers, and tap into what was consistently cited as the main gambling trigger amongst respondents. As such, more transparency around promotional offers would give online bookmakers the opportunity to differentiate themselves away from the perception of gambling companies as “looking out for themselves” (Interview3), and demonstrate a more responsible approach to advertising promotions. In this way, OSG bookmakers need not make the choice between maximising revenue or minimising harm (Soriano et al. 2012), instead they can work to establish a greater degree of trust between customer and company (Shelat and Egger 2002) that would benefit both parties. For example, respondents frequently expressed views that OSG bookmakers focus too much on the new customer market, and suggested bookmakers extend advertising promotional offers or create “loyalty schemes” (Interview1) for existing customers.

Through careful, targeted marketing, online bookmakers can demonstrate the value of existing customers (Berry et al. 2006; Hanif et al. 2010) and reward their loyalty, thus reducing the risk of customers feeling “cast asunder” (Interivew1). This will in turn reduce existing customers’ desire to “switch between websites” (Interview9) in order to take advantage of promotional sign-up offers. Results suggest that customers generally had little knowledge of such loyalty schemes or rewards as currently present, although it was agreed that this would be a positive step towards making existing customers feel “valued” (Interview10), while generating no concerns of irresponsible marketing.

Of the varied marketing tactics identified by young adult respondents, few concerns were raised from a responsible marketing perspective. However, the most widely criticised tactic, that has also received an apparent lack of coverage in academic literature, was the timing and placement of OSG advertisements. The noticeable increase in advertisements around televised sporting events and the spread of OSG marketing on social media such as Twitter, was described as “intrusive” (Interview9) and considered a feature of OSG marketing which could cause potential collateral damage to problem gamblers and children (under 18). OSG bookmakers must therefore remain wary of any increase in the clear grouping of advertisements around sporting events. The utilisation of advertisements focused on promotional offers should replace, rather than being in addition to, existing advertisements. In altering the content of existing advertising, rather than simply increasing its volume to accommodate promotion-based advertising, OSG companies can more closely align to customer requirements, while avoiding a potential increase in collateral damage to vulnerable groups that may arise as a result of increased OSG advertising. It should be noted that the sample of interviewees in this study were all young male OSG participants, an inevitable byproduct of the purposive sampling approach, which could be a factor in there being few objections raised to current OSG advertising tactics from a responsible marketing perspective, beyond the issues of volume and timing of advertisements. Despite this limitation, however, the current marketing tactics employed by OSG companies were largely accepted as responsible across our participant sample. Further research is required to determine whether these findings can be generalised to all OSG participants.

Conclusions and future directions

Gambling triggers were found to match many of those posited in literature. Amongst our sample, young adults gambling relatively small amounts of money, around £5 a week, the excitement of OSG was their main trigger. Promotional offers were almost exclusively cited as the marketing technique most likely to influence the gambling habits of young adults, with respondents regularly describing their tendency to open up accounts on new websites as a result, in line with McGee (2020).

The marketing techniques consumers were able to recall as currently in use largely mirrored those described in literature. These included ‘glamourisation’; humour and creativity; and enhancing the amount of perceived skill involved in online gambling. The timing and placement of OSG advertisements was also raised by respondents, despite receiving a lack of coverage in literature. In addition, the presence of promotional offers in marketing efforts was widely cited by respondents, however it is a phenomenon seldom mentioned in current research. Both findings reflect Griffiths’ (2005) and McGee’s (2020) claims that gambling advertisements are an under-researched area. Few objections were raised to each marketing tactic’s use from a responsible marketing perspective. Consumers often viewed OSG marketing as akin to the marketing of other industries, in that its purpose was to highlight the positive aspects of the product and ignore any negative features. Respondents did notice the obvious clustering of advertisements around sporting events, however this phenomenon was accepted as an understandable attempt by OSG companies to attract business during their peak times. Of the few responsible marketing objections raised, the most frequent was the potential effect OSG marketing could have on problem gamblers and children (under 18). However this was not deemed to be a particularly pressing concern in the eyes of consumers, as none felt that OSG bookmakers were directly targeting these customers and concerns were more focused on potential collateral damage, a view supported from within the industry.

Our findings indicate that companies in this industry could benefit from a greater focus on promotions to market their product more effectively while remaining responsible. Transparency was found to be a crucial part of advertising promotions; ensuring customers were free from a negative first experience with a new company. The interviews revealed that young adult consumers rarely felt valued by the companies they currently gamble with, and instances where bookmakers demonstrated the value of existing customers served to increase customer loyalty, a finding supported in the literature (Berry et al. 2006; Hanif et al. 2010).

From these conclusions, a number of recommendations can be made to OSG bookmakers who wish to market their product successfully in a responsible manner, separate to the regulatory requirement of including explicit ‘responsible gambling’ information throughout an advertisement. Firstly, regardless of the age profile or demographic of the target customers, promotional offers for OSG need to be more transparent in order to mitigate against negative experiences arising from unclear terms and conditions, which have been shown to be catastrophic with respect to customer loyalty and repeat business. Additionally, OSG retailers can be more proactive with respect to valuing existing customers, through introducing and promoting loyalty schemes for such customers. This is likely to have a positive effect on customer loyalty and could therefore nullify the tendency of young adults to take advantage of promotional sign up offers across multiple bookmaker websites.

In addition to a greater focus on promotional offers, OSG bookmakers can continue to use the same marketing tactics as currently employed, without fear of irresponsible marketing. OSG companies should, however, be wary of how the growth in marketing efforts may impact upon vulnerable groups, such as problem gamblers and children (under 18).

Data collected from a source inside the gambling industry provided a useful insight into the thoughts behind the marketing of OSG. Research to determine the extent to which online gambling retailers consider the potentially negative consequences of their marketing campaigns in relation to problem or underage gamblers, is largely neglected by academics. While the collection of data may prove difficult, further research in this area would prove interesting and important for researchers in the field. It would also serve as research against which the findings of this paper and others could be compared. In addition, research on whether the findings previously outlined are replicated when interviewing a sample of non-gamblers will provide either additional credence or a challenge to the conclusions and recommendations made in this paper.

References

Adams PJ, Raeburn J, de Silva K (2009) A question of balance: prioritizing public health responses to harm from gambling. Addiction 104:688–691

BBC (2020) Fair Game? The secrets of football betting. Accessed 10 Apr 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3wwtKpxB40tC6P4K15Y23j5/fair-game-the-secrets-of-football-betting

BeGambleAware (2020) Be Gamble Aware. Accessed 17 May 2020. https://www.begambleaware.org

Berry LL, Wall EA, Carbone LP (2006) Service clues and customer assessment of the service experience: Lessons from marketing. Acad Manag Perspect 20(2):43–57

Bhattacharya CB, Sen S (2004) Doing better at doing good: when, why and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif Manag Rev 47(1):9–24

Binde P (2009) You could become a millionaire: truth, deception and imagination in gambling advertising. Global gambling: cultural perspectives on gambling organizations, Routledge

Binde P (2014) Gambling advertising: a critical research review. Responsible Gambling Trust, London

Blair JA (1996) The possibility and actuality of visual arguments. Argum Advocacy 33(1):23–39

Blakemore E (2015) How much time do you spend online? Accessed 19 Aug 2020. http://www.tweentribune.com/article/tween56/how-much-time-do-you-spend-online/

Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Nower L, Shaffer HJ (2008) Informed choice and gambling: principles for consumer protection. J Gambl Bus Econ 2:103–118

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101

Brindley C (1999) The marketing of gambling on the Internet. Internet Res 9(4):281–286

Brown SJ (2006) The surge in online gambling on college campuses. New Dir Stud Serv 113:53–61

Campaign (2014) Ladbrokes “the Ladbrokes life” by Bartle Bogle Hegarty. Accessed 25 Oct 2020. https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/ladbrokes-the-ladbrokes-life-bartle-bogle-hegarty/1291765

Campaign (2018) Paddy Power advertising, marketing campaigns and videos. Accessed 25 Oct 2020. https://www.campaignlive.co.uk/the-work/advertiser/paddy-power/7737

Cassidy R, Ovenden N (2017) Frequency, duration and medium of advertisements for gambling and other risky products in commercial and public service broadcasts of English Premier League football. Accessed 10 Aug 2020. https://osf.io/gprkv/?action=download

Derevensky J (2008) Youth gambling problems: the hidden addiction. In: Kaminer Y, Buckstein OG (eds) Adolescent substance abuse: psychiatric comorbidity and high risk behaviors. Haworth, New York

Derevensky J, Sklar A, Gupta R, Messerlian C (2010) An empirical study examining the impact of gambling advertisements on adolescent gambling attitudes and behaviors. Int J Ment Health Addict 8(1):21–34

Dyall L, Tse S, Kingi A (2009) Cultural icons and marketing of gambling. Int J Ment Heal Addict 7:84–96

Eadington WR (2004) The future of online gambling in the united states and elsewhere. J Public Policy Mark 23:214–219

Easterby-Smith M, Thorpe R, Jackson PR (2015) Management and business research. Sage, London

Eggert K (2004) Truth in gaming: toward consumer protection in the gaming industry. Md Law Rev 63:217–286

Financial Times (2018) Online gambling: the hidden epidemic. Accessed 10 Aug 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/7044b142-7313-11e8-aa31-31da4279a601

Floros GD (2018) Gambling disorder in adolescents: prevalence, new developments, and treatment challenges. Adolesc Health Med Ther 9:43–51

Gambling Commission (2020) Industry statistics. Accessed 2 Feb 2021. https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/news-action-and-statistics/Statistics-and-research/Statistics/Industry-statistics.aspx

GamCare (2020) Why do people gamble? http://www.gamcare.org.uk/get-advice/why-do-people-gamble. Accessed 10 Aug 2020

Gardner MP (1985) Mood states and consumer behaviour. A critical review. J Consum Res 12:281–300

Gilovich T (1983) Biased evaluation and persistence in gambling. J Pers Soc Psychol 44:1110–1126

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine, Chicago

Griffiths MD (2005) Does advertising of gambling increase gambling addiction? Int J Ment Heal Addict 3(2):15–25

Griffiths MD, Parke J (2002) The social impact of internet gambling. Soc Sci Comput Rev 20(3):312–320

Griffiths M, Parke A, Wood R, Parke J (2006) Internet gambling: an overview of psychosocial impacts. UNLV Gaming Res Rev J 10(1):27–39

Griffiths MD, Wood R, Parke J (2009) Social responsibility tools in online gambling: a survey of attitudes and among Internet gamblers. Cyberpsychol Behav 12(4):413–421

Guardian (2013) TV gambling ads have risen 600% since law change. Accessed 24 Jan 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2013/nov/19/tv-gambling-ads

Guardian (2016) EU referendum is bookies biggest ever non-sporting event. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/jun/22/eu-referendum-is-bookies-biggest-ever-non-sporting-event. Accessed 20 Aug 2020

H2 Gambling Capital (2017) Global gambling data and intelligence subscription service, global summary dataset. Accessed 28 June 2020. https://h2gc.com

Halls B (2016) How twitter tipsters are profiting on losing bets. Accessed 20 Aug 2020. https://sports.vice.com/en_uk/article/a-mugs-game-how-twitter-tipsters-are-profiting-on-losing-bets

Hanif M, Hafeez S, Riaz A (2010) Factors affecting customer satisfaction. Int Res J Finance Econ 60(1):44–52

Healthy Place (2020) Reasons for Gambling. Accessed 4 May 2020. http://www.healthyplace.com/addictions/gambling-addiction/psychology-of-gambling-reasons-for-gambling/

Heath R, Brandt D, Nairn A (2006) Brand relationships: strengthened by emotion, weakened by attention. J Advert Res 46:410–419

Hing N, Russell AMT, Lamont M et al (2017) Bet anywhere, anytime: an analysis of internet sports bettors’ responses to gambling promotions during sports broadcasts by problem gambling severity. J Gambl Stud 33(4):1051–1065

ICO (2018) Guide to the general data protection regulation (GDPR). Accessed 2 Feb 2021. https://ico.org.uk/media/for-organisations/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr-1-0.pdf

James RJE, O’Malley C, Tunney RJ (2017) Understanding the psychology of mobile gambling: a behavioural synthesis. Br J Psychol 108(3):608–625

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47(2):263–291

Kanne J, Dunch D, Tone J, Schellinger N, Bechen E, Allrich H, Moon J, McCarthy S, Vidunas L, Calderon N, Tieu A (2002) You’re so money. Metro 1:7–14

Kennedy J (2018) Privacy by default: GDPR will change the rules of marketing forever. Accessed 2 Feb 2021. https://www.siliconrepublic.com/enterprise/marketing-gdpr-consent-privacy

Killick A, Griffiths MD (2019) A content analysis of gambling operators’ twitter accounts at the start of the English premier league football season. J Gambl Stud 36:319–341

King N (2004) Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Cassell C, Symon G (eds) Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. Sage, London, pp 257–270

Korn DA, Shaffer HJ (1999) Gambling and the health of the public: adopting a public health perspective. J Gambl Stud 15:289–365

Kvale S (1994) InterViews: an introduction to qualitative research writing. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

LaBrie R, Shaffer HJ (2011) Identifying behavioral markers of disordered Internet sports gambling. Addict Res Theory 19(1):56–65

Lemarié L, Chebat JC (2017) The best defense can be a good offense. Promoting responsible gambling among youth. The customer is NOT always right? Marketing orientations in a dynamic business world. Springer, Cham, pp 497–505

Leung TCH, Gray R (2016) Social responsibility disclosure in the international gambling industry: a research note. Medit Account Res 24

Leung TCH, Snell RS (2017) Attraction or distraction? Corporate social responsibility in Macao’s Gambling Industry. J Bus Ethics 415(3):673–685

Livingstone C, Adams PJ (2011) Harm promotion: observations on the symbiosis between government and private industries in Australasia for the development of highly accessible gambling markets. Addiction 106:3–8

Lopez-Gonzalez H, Estévez A, Griffiths MD (2018a) Controlling the illusion of control: a grounded theory of sports betting advertising in the UK. Int Gambl Stud 18(1):39–55

Lopez-Gonzalez H, Guerrero-Solé F, Estévez A et al (2018b) Betting is loving and bettors are predators: a conceptual metaphor approach to online sports betting advertising. J Gambl Stud 34(3):709–726

Maher A, Wilson N, Signal L, Thomson G (2006) Patterns of sports sponsorship by gambling, alcohol and food companies: an internet survey. BMC Public Health 6(1):95

Matthews N, Farnsworth B, Griffiths MD (2009) A pilot study of problem gambling among student online gamblers: mood states as predictors of problematic behavior. Cyberpsychol Behav 12(6):741–745

McGee D (2020) On the normalisation of online sports gambling among young adult men in the UK: a public health perspective. Public Health 184:89–94

McMullan J (2011) Gambling advertising and online gambling. Accessed 6 Aug 2020. http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/committee/gamblingreform_ctte/interactive_online_gambling_advertising/submissions.htm

McMullan JL, Miller D (2009) Wins, winning and winners: the commercial advertising of lottery gambling. J Gambl Stud 25:273–295

Mental Health Foundation (2020) Gambling. Accessed 4 May 2020. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/a-to-z/g/gambling

Monaghan S, Derevensky J (2008) An appraisal of the impact of the depiction of gambling in society on youth. Int J Ment Heal Addict 6:1557–1574

Monaghan S, Derevensky J, Sklar A (2008) Impact of gambling advertisements and marketing on children and adolescents: Policy recommendations to minimise harm. J Gambl Issues 22:252–274

Neighbors C, Lostutter TW, Cronce JM, Larimer ME (2002) Exploring college student gambling motivation. J Gambl Stud 18:361–370

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ (2017) Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods 16:1–13

Ofcom (2013) Trends in advertising activity-gambling. Accessed 2 Feb 2021. http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/tv-research/Trends_in_Ad_Activity_Gambling.pdf?utm_source=updates&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=gambling-ads

Petry NM (2006) Internet gambling: an emerging concern in family practice medicine? Fam Pract 23:421–426

Pettigrew A, McNulty T (1995) Power and influence in and around the boardroom. Hum Relat 48(8):845–873

Premier League (2020) Accessed 11 June 2020. https://www.premierleague.com/clubs

Read S (2015) The new financial crisis: young people are facing a debt trap, Evening Standard. Accessed 29 Sep 2015

Remote Gambling Association (2010) Sports betting: legal, commercial and integrity issues. Accessed 17 Aug 2020. http://www.rga.eu.com/data/files/Pressrelease/sports_betting_web.pdf

Rosecrance JD (1986) Attributions and the origins of problem gambling. Sociol Quart 27:463–477

Ryan GW, Bernard HR (2003) Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 15:85–109

Saffer H, Dave D (2002) Alcohol consumption and alcohol advertising bans. Appl Econ 34(11):1325–1334

Schwartz DG (2006) Roll the bones: the history of gambling. Winchester Books, Las Vegas

Shelat B, Egger FN (2002) What makes people trust online gambling sites? Ext Abstr Hum Factors Comput Syst 852–855

Siegfried N, Pienaar DC, Ataguba JE, Volmink J, Kredo T, Jere M, Parry CDH (2014) Restricting or banning alcohol advertising to reduce alcohol consumption in adults and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev

SkyBet (2020) Accessed 5 Apr 2020. https://www.skybet.com

Soriano M, Javed U, Yousafzai S (2012) Can an industry be socially responsible if its products harm consumers? The case of online gambling. J Bus Ethics 110(4):481–497

Statista (2020) Gambling industry in the United Kingdom (UK)—statistics and figures. Accessed 6 Apr 2020. https://www.statista.com/topics/3400/gambling-industry-in-the-united-kingdom-uk/

Strautz K, Marteau TM (2016) Viewing alcohol warning advertising reduces urges to drink in young adults: an online experiment. BMC Public Health 16:530

The Economist (2017) The World’s biggest gamblers. Accessed 10 Aug 2020. https://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2017/02/daily-chart-4

The Telegraph (2018) A fifth of 16–24 year olds spend more than 7 hours a day online every day of the week, exclusive Ofcom figures reveal. Accessed 2 Feb 2021. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/08/11/fifth-16-24-year-olds-spend-seven-hours-day-online-every-day/

Walters J (2005) Computer friendly: gambling has found a growing fan base online. Accessed 15 Aug 2020. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2005/more/05/23/internet.poker/index.html

Ward D (2005) Make room for generation net: a cultural imperative. Defense AT and L, 56

Wardle H (2007) British gambling prevalence survey 2007. UK National Centre for Social Research, London

Wheeler S, Round D, Wilson J (2010) The relationship between crime and gaming expenditure in Victoria. Department of Justice, Melbourne

Williams RJ, Rehm J, Stevens RMG (2011) The social and economic impacts of gambling. Victorian Gambling Research Panel, Melbourne

Wood RT, Williams RJ (2007) Problem gambling on the internet: implications for Internet Gambling Policy in North America. New Media Soc 9(3):520–542

Wood RT, Griffiths M, Parke J (2007) Acquisition, development, and maintenance of online poker playing in a student sample. Cyberpsychol Behav 10:354–361

Zangeneh M, Griffiths M, Parke J (2008) The marketing of gambling. In: Zangeneh M, Blaszczynski A, Turner NE (eds) In the pursuit of winning. Springer, Boston

Zewe C (1998) Should online gambling be regulated? Accessed 2 Feb 2021. http://www.cnn.com/TECH/computing/9803/12/internet.gambling/

Funding

No financial support was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dunlop, P., Ballantyne, E.E.F. Effective and responsible marketing of online sports gambling to young adults in the UK. SN Bus Econ 1, 124 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-021-00125-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-021-00125-x