Abstract

Introduction

Potentially harmful excipients (PHEs) for children have been reported and the need for information collection has been advocated. However, studies on the actual occurrence of adverse events are limited. This study investigated the quantitative exposure of PHEs via injection and their association with adverse events in children under 2 years of age.

Materials and Methods

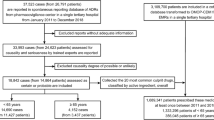

As a single-center observational study, children aged 0–23 months received injectable drugs from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2023 were included. Information on PHE exposure and adverse events after administration were extracted from medical records. Sodium benzoate, benzyl alcohol, ethanol, glycerol, lactose, polyethylene glycol paraben, polysorbate, propylene glycol, sorbitol, sucrose, sulfite, and thimerosal were selected as PHEs.

Results and Discussion

6265 cases, 333,694 prescriptions, and 368 drugs (264 ingredients) were analyzed. The median age was 0.63 years (interquartile range [IQR] 0.1–1.1). 72,133 prescriptions, 132 drugs and 99 ingredients contained PHE; 2,961 cases exposed to PHE and 1825 cases exceeding permitted daily exposure. The drug with the highest number of exposure cases was hydroxyzine, and the highest number of prescriptions was heparin (both drugs contain benzyl alcohol). In association between adverse events and PHE exposure, higher doses in cases of adverse event occurrence were found in benzyl alcohol, glycerol, polyethylene glycol, and polysorbate exposed cases. Among thimerosal-exposed cases, “developmental delay” was more frequent in exposed cases, but the causal relationship was unknown. Further investigation is needed to clarify the relationship between adverse events and PHE exposure. Additionally, more precise information on PDE for pediatrics including neonates is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Fabiano V, Mameli C, Zuccotti GV. Paediatric pharmacology: remember the excipients. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:362–5.

Salunke S. Thesis. University College London; London, UK: 2017. Development and Evaluation of Database of Safety and Toxicity of Excipients for Paediatrics (STEP Database). https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1546094/ Accessed on 1 August 2023.

Salunke S, Giacoia G, Tuleu C. The STEP (safety and toxicity of excipients for paediatrics) database. Part 1-A need assessment study. Int J Pharm. 2012;435:101–11.

Soremekun R, Ogbuefi I, Aderemi-Williams R. Prevalence of ethanol and other potentially harmful excipients in pediatric oral medicines: survey of community pharmacies in a Nigerian City. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:1–5.

Nakama K, Dos Santos R, Serpa P, et al. Organoleptic excipients used in pediatric antibiotics. Arch Pédiatrie. 2019;26:431–6.

Kriegel C, Festag M, Kishore RS, et al. Pediatric safety of polysorbates in drug formulations. Children. 2019;7:1.

Akinmboni TO, Davis NL, Falck AJ, et al. Excipient exposure in very low birth weight preterm neonates. J Perinatol. 2018;38:169–74.

Fister P, Urh S, Karner A, et al. The prevalence and pattern of pharmaceutical and excipient exposure in a neonatal unit in Slovenia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:2053–61.

Cuzzolin L. Neonates exposed to excipients: concern about safety. J Pediatr and Neonat Individualized Med. 2018;7: e070112.

Nellis G, Metsvaht T, Varendi H, et al. ESNEE consortium. Potentially harmful excipients in neonatal medicines: a pan-European observational study. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:694–9.

Koshi B, Grapci AD, Nebija D, et al. The potentially harmful excipients in prescribed medications in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Kosovo and available safer alternatives. Turk J Pediatr. 2022;64:49–58.

Lass J, Naelapää K, Shah U, et al. Hospitalised neonates in Estonia commonly receive potentially harmful excipients. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:136.

Saito J, Nadatani N, Setoguchi M, et al. Potentially harmful excipients in neonatal medications: a multicenter nationwide observational study in Japan. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2021;7:23.

Sviestina I, Mozgis D. A retrospective and observational analysis of harmful excipients in medicines for hospitalised neonates in Latvia. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2018;25:176–82.

Garcia-Palop B, Polanco EM, Ramirez CC, Poy MJC. Harmful excipients in medicines for neonates in Spain. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:238–42.

Souza A Jr, Santos D, Fonseca S, et al. Toxic excipients in medications for neonates in Brazil. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:935–45.

Salunke S, Brandys B, Giacoia G, et al. The STEP (safety and toxicity of excipients for paediatrics) database: part 2—the pilot version. Int J Pharm. 2013;457:310–22.

Cañete CR, García MP, García BP, et al. Formulación magistral y excipientes en pediatría. El Farma-céutico Hospitales. 2018;213:22–8.

Parneli C, Srivari Y, Meiki Y, et al. Pharmaceutical excipients and paediatric formulations. Chem Today. 2012;30:56–61.

Peiré MAG (2019) Farmacología Pediátrica, 1st ed, Ediciones Journal: Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Rowe RC, Sheskey PJ, Owen SC. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients. 6th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2006.

Valeur KS, Hertel SA, Lundstrøm KE, et al. Safe excipient exposure in neonates and small children—Protocol for the SEEN project. Dan Med J. 2017;64:A5324.

Horinek EL, Kiser TH, Fish DN, et al. Propylene glycol accumulation in critically ill patients receiving continuous intravenous lorazepam infusions. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1964–71.

Shehab N, Lewis CL, Streetman DD, et al. Exposure to the pharmaceutical excipients benzyl alcohol and propylene glycol among critically ill neonates. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:256–9.

Mulla H, Yakkundi S, McElnay J, et al. An observational study of blood concentrations and kinetics of methyl- and propyl-parabens in neonates. Pharm Res. 2015;32:1084–93.

Evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. Forty-sixth report of the Joint FAO/WHO expert committee on food additives. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1997;868:1–69.

Aguilar F, Crebelli R, Domenico AD, et al. Scientific opinion on the re-evaluation of benzoic acid (E 210), sodium benzoate (E 211), potassium benzoate (E 212) and calcium benzoate (E 213) as food additives. EFSA J. 2016;14:4433.

SCF (Scientific Committee on Food) (2023) Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on Benzoic acid and its salts, SCF/CS/ADD/CONS/48 Final, September 2002. https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-12/sci-com_scf_out137_en.pdf Accessed 10 Aug 2023.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Questions and answers on benzoic acid and benzoates used as excipients in medicinal products for human use EMA/CHMP/508189/2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/questions-answers-benzoic-acid-benzoates-used-excipients-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf Accessed 10 Aug 2023.

Hannah K, John F. Formulations for children: problems and solutions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79:405–18.

Rowe RC. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients. 7th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2012.

Gold S (2006) Reflection paper: formulations of choice for the pediatric population. Eur Medic Agen. 2006. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/formulations-choice-paediatric-population. Accessed 10 Aug 2023.

Cronin CM, Brown DR, Ahdab-Barmada M. Risk factors associated with kernicterus in the newborn infant: importance of benzyl alcohol exposure. Am J Perinatol. 1991;8:80–5.

Walsh J, Mills S. Conference report: formulating better medicines for children: 4th European paediatric formulation initiative conference. Ther Deliv. 2013;4:21–5.

World Health Organizations (2012) Development of Pediatric Medicines: Points to Consider in the Formulation. Geneva: WHO technical report series 2012. https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js19833en. Accessed 10 Aug 2023.

Younes M, Aquilina G, Castle L, et al. Scientific opinion on the re-evaluation of benzyl alcohol (E 1519) as food additive. EFSA J. 2019;17:5876–901.

Rouaz K, Chiclana-Rodríguez B, Nardi-Ricart A, et al. Excipients in the paediatric population: a review. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:387.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Questions and answers on benzyl alcohol used as an excipient in medicinal products for human use EMA/CHMP/508188/2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/questions-answers-benzyl-alcohol-used-excipient-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf. Accessed 10 August 2023.

Hiller JL, Benda GI, Rahatzad M, et al. Benzyl alcohol toxicity: impact on mortality and intraventricular hemorrhage among very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1986;77:500–6.

Jardine D, Rogers K. Relationship of benzyl alcohol to kernicterus, intraventricular hemorrhage, and mortality in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 1989;83:153–60.

Benda GI, Hiller JL, Reynolds JW. Benzyl alcohol toxicity: impact on neurologic handicaps among surviving very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1986;77:507–12.

Mark K, Kelly DK, Kent EV. Treatment of Infectious Diseases. In: Mark K, Kelly DK, Kent EV, editors. Elsevier’s Integrated Review Pharmacology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. p. 41–78.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Information for the package leaflet regarding ethanol used as an excipient in medicinal products for human use EMA/CHMP/43486/2018 Corr. 1. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/information-package-leaflet-regarding-ethanol-used-excipient-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf Accessed on 10 August 2023.

Sun C, Nie Y, Cui X, et al. Neonatal acute ethanol intoxication during the epidemic of COVID-19: a case report. BMC Pediatr. 2022;22:53.

Nahata MC. Safety of “inert” additives or excipients in paediatric medicines. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F392–3.

LaHood AJ, Kok SJ. Ethanol Toxicity. Tampa: StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

EFSA Ans Panel (EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food), Mortensen A, Aguilar F, Crebelli R, Di Domenico A, Dusemund B, Frutos MJ, Galtier P, Gott D, Gundert-Remy U, Leblanc J-C, et al. Scientific opinion on the re-evaluation of glycerol (E 422) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2017;15:4720–84.

Noel KM, Carolyn C, Pinar TO, et al. Glycerol intolerance in a child with intermittent hypoglycemia. J Pediatrics. 1975;86:43–9.

Tildon J, Ozand P, Karahasan A, et al. Biochemical Studies of Glycerol Neurotoxicity. Pediatr Res. 1976;10:895.

Katayama S, Nunomiya S, Wada M, et al. Hyperlactatemia caused by intra-venous administration of glycerol: A case study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2012;16:241–4.

Katayama S, Tonai K, Goto Y, et al. Transient hyperlactatemia during intravenous administration of glycerol: a prospective observational study. J Intensive Care. 2018;6:55.

Schott HC, Düsterdieck KF, Eberhart SW, et al. Effects of electrolyte and glycerol supplementation on recovery from endurance exercise. Equine Vet J Suppl. 1999;30:384–93.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Information for the package leaflet regarding lactose used as an excipient in medicinal products for human use EMA/CHMP/186428/2016. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-information-package-leaflet-regarding-lactose-used-excipient-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf Accessed 10 August 2023.

Di Costanzo M, Biasucci G, Maddalena Y, et al. Lactose intolerance in pediatric patients and common misunderstandings about cow’s milk allergy. Pediatr Ann. 2021;50:e178–85.

Santoro A, Andreozzi L, Ricci G, et al. Allergic reactions to cow’s milk proteins in medications in childhood. Acta Biomed. 2019;90:91–3.

Agency EFS. Opinion of the scientific panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food on a request from the commission related to para hydroxybenzoates (E 214–219). The EFSA J. 2004;83:1–26.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Reflection paper on the use of methyl- and propylparaben as excipients in human medicinal products for oral use. EMA/CHMP/SWP/272921/2012. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-use-methyl-propylparaben-excipients-human-medicinal-products-oral-use_en.pdf Accessed on 10 August 2023.

Rasmussen LF, Ahlfors CE, Wennberg RP. The effect of paraben preservatives on albumin binding of bilirubin. J Pediatr. 1976;89:475–8.

European Agency (2023) Polyethylene glycol stearates and polyethylene glycol 15 hydroxy stearate. Committee for veterinary medicinal products. EMEA/MRL/392/98-FINAL-Rev.1. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/mrl-report/polyethylene-glycol-stearates-polyethylene-glycol-15-hydroxystearate-summary-report-committee_en.pdf Accessed 10 August 2023.

Younes M, Aggett P, Aguilar F, et al. Refined exposure assessment of polyethylene glycol (E 1521) from its use as a food additive. EFSA J. 2018;16: e05293.

Cheng CL, Liu NJ, Tang JH, et al. Risk of renal injury after the use of polyethylene glycol for outpatient colonoscopy: a prospective observational study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:e444–50.

Laine GA, Hossain SH, Solis RT, et al. Polyethylene glycol nephrotoxicity secondary to prolonged high-dose intravenous lorazepam. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:1110–4.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Information for the package leaflet regarding polysorbates used as excipients in medicinal products for human use EMA/CHMP/190743/2016. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/draft-information-package-leaflet-regarding-polysorbates-used-excipients-medicinal-products-human_en.pdf Accessed 10 August 2023.

Bodenstein CJ. Intravenous vitamin E and deaths in the intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 1984;73:733.

Munoz A, Karila P, Gallay P, et al. A randomized 1266 hemodynamic comparison of intravenous amiodarone with and without Tween 80. Eur Heart J. 1988;9:142–8.

Masini E, Planchenault J, Pezziardi F, et al. Histamine-releasing properties of Polysorbate 80 in vitro and in vivo: correlation with its hypotensive action in the dog. Agents Actions. 1985;16:470–7.

Masi S, de Cléty SC, Anslot C, et al. Acute amiodarone toxicity due to an administration error: could excipient be responsible? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:691–3.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Questions and Answers on Benzyl alcohol in the context of the revision of the guideline on ‘Excipients in the label and package leaflet of medicinal products for human use’ (CPMP/463/00) EMA/CHMP/508188/2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/questions-answers-benzyl-alcohol-used-excipient-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf Accessed 10 August 2023.

Bove KE, Kosmetatos N, Wedig KE, et al. Vasculopathic hepatotoxicity associated with E-Ferol syndrome in low-birth-weight infants. JAMA. 1985;254:2422–30.

Chen CC, Wu CC. Acute hepatotoxicity of intravenous amiodarone: case report and review of the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e260–3.

Jennifer SK, Julie AH, Marcia LB. Hepatotoxicity after continuous amiodarone infusion in a postoperative cardiac infant. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2012;17:189–95.

Kevin EB, Niki K, Kathryn EW, et al. Vasculopathic hepatotoxicity associated with E-Ferol syndrome in low-birth-weight infants. JAMA. 1985;254:2422–30.

Kicker JS, Haizlip JA, Buck ML. Hepatotoxicity after continuous amiodarone infusion in a postoperative cardiac infant. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2012;17:189–95.

Shelley WB, Talanin N, Shelley ED. Polysorbate 80 hypersensitivity. Lett Ed Lancet. 1995;345:1312–3.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Questions and answers on propylene glycol used as an excipient in medicinal products for human use EMA/CHMP/704195/2013. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/questions-answers-propylene-glycol-used-excipient-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf Accessed 10 August 2023.

Kulo A, Hoon J, Allegaert K. The propylene glycol research project to illustrate the feasibility and difficulties to study toxicokinetics in neonates. Int J Pharm. 2012;435:112–4.

Morizono T, Johnstone BM. Ototoxicity of chloramphenicol ear drops with propylene glycol as solvent. Med J Aust. 1975;2:634–8.

Yahwak J, Riker R, Fraser G. Determination of a lorazepam dose threshold for using the osmol gap to monitor for propylene glycol toxicity. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:984–91.

Yaucher N, Fish J. Propylene glycol-associated renal toxicity from lorazepam infusion. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:1094–9.

O’Donnell J, Mert SL, Kelly WN. Propylene glycol toxicity in a pediatric patient: the dangers of diluents. J Pharm Pract. 2000;13:214–24.

European Medicines Agency (2023) Information for the package leaflet regarding fructose and sorbitol used as excipients in medicinal products for human use EMA/CHMP/460886/2014. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/information-package-leaflet-regarding-fructose-sorbitol-used-excipients-medicinal-products-human-use_en.pdf Accessed 10 August 2023.

Ballow M, Pinciaro PJ, Craig T, et al. Flebogamma 5% DIF intravenous immunoglobulin for replacement therapy in children with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36:583–9.

Chakraborty S, Filippi CG, Wong T, et al. Superselective intraarterial cerebral infusion of cetuximab after osmotic blood/brain barrier disruption for recurrent malignant glioma: phase I study. J Neurooncol. 2016;128:405–15.

Ionova Y, Wilson L. Biologic excipients: importance of clinical awareness of inactive ingredients. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0235076.

Yalcin AD, Gorczynski RM, Cilli A, Strauss L. Omalizumab (anti-IgE) therapy increases blood glucose levels in severe persistent allergic asthma patients with diabetes mellitus: 18 month follow-up. Clin Lab. 2014;60:1561–4.

Wajanaponsan N, Cheng SF. Acute renal failure resulting from intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Hawaii Med J. 2004;63:266–7.

Dantal J. Intravenous immunoglobulins: in-depth review of excipients and acute kidney injury risk. Am J Nephrol. 2013;38:275–84.

Vally H, Misso NL, Madan V. Clinical effects of sulphite additives. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1643–51.

Vally H, Misso NL. Adverse reactions to the sulphite additives. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5:16–23.

Hugues FC, Le JC, Haas C. Bronchial manifestation of drug-induced complications. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 1989;140:585–8.

Dalton-Bunnow MF. Review of sulfite sensitivity. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1985;42:2220–6.

Taylor SL, Bush RK, Selner JC, et al. Sensitivity to sulfited foods among sulfite-sensitive subjects with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;81:1159–67.

Randolph TC. Sulfite sensitivity. Ann Allergy. 1987;58:386.

Acosta R, Granados J, Mourelle M, et al. Sulfite sensitivity: relationship between sulfite plasma levels and bronchospasm: case report. Ann Allergy. 1989;62:402–5.

Gunnison AF, Jacobsen DW. Sulfite hypersensitivity: a critical review. CRC Crit Rev Toxicol. 1987;17:185–214.

Schwartz HJ. Observations on the use of oral sodium cromoglycate in a sulfite-sensitive asthmatic patient. Ann Allergy. 1986;57:36–7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations regarding the use of vaccines that contain thimerosal as a preservative. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:996–8.

Zheng W, Dreskin SC. Thimerosal in influenza vaccine: an immediate hypersensitivity reaction. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:574–5.

McNeil MM, DeStefano F. Vaccine-associated hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:463–72.

Dórea JG. Low-dose Thimerosal in pediatric vaccines: adverse effects in perspective. Environ Res. 2017;152:280–93.

Hurley AM, Tadrous M, Miller ES. Thimerosal-containing vaccines and autism: a review of recent epidemiologic studies. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2010;15:173–81.

Geier DA, King PG, Hooker BS, et al. Thimerosal: clinical, epidemiologic and biochemical studies. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;444:212–20.

McCabe WR, Jackson GG, Grieble HG. Treatment of chronic pyelonephritis. Arch Intern Med. 1959;104:710–709.

Institute of Medicine (US) Immunization Safety Review Committee. Immunization Safety Review: Thimerosal-Containing Vaccines and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Washington: National Academies Press; 2001.

Clements CJ. The evidence for the safety of thiomersal in newborn and infant vaccines. Vaccine. 2004;22:1854–61.

Hooker B, Kern J, Geier D, et al. Methodological issues and evidence of malfeasance in research purporting to show thimerosal in vaccines is safe. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014: 247218.

Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:295–300.

Funding

This work was conducted as part of “Regulatory science for better access to paediatric drugs in Japan (23mk0101243H0002)” awarded to HN. (Department of Research and Development Supervision, National Center for Child Health and Development) with support from the Research Program of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS: has contributed to drafting the work, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. HN: has contributed to the conception. AY and MA: have contributed to the conception or design of the work, drafting, and revising the work critically for important intellectual content. All authors are responsible for the final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, J., Nakamura, H., Akabane, M. et al. Quantitative Investigation on Exposure to Potentially Harmful Excipients by Injection Drug Administration in Children Under 2 Years of Age and Analysis of Association with Adverse Events: A Single-Center, Retrospective Observational Study. Ther Innov Regul Sci 58, 316–335 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-023-00596-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-023-00596-0