Abstract

Background

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) began collaboration on Good Clinical Practice (GCP) inspections for marketing applications since 2009. The main characteristics of the GCP inspection processes between FDA and EMA were never evaluated. This is the first analysis comparing the GCP inspection processes between the two agencies.

Methods

We examined and analyzed the key characteristics of the GCP inspection processes, including the geographical distribution, inspection types and timelines from application submission to final inspection reporting for marketing applications from September 2009 through December 2015.

Results

Fifty-five shared applications were included for analysis. For these applications, a total of 433 GCP inspections were conducted in 47 countries. Most clinical investigator (CI) inspections were conducted in regions outside of each agency’s own regulatory jurisdiction, while most sponsor/contract research organization (CRO) inspections were conducted in the U.S. by both agencies. Twenty-eight shared applications included common sites inspected by both agencies. There were 15 joint inspections conducted for seven of these applications and the remaining applications had common sites inspected by both agencies at separate times. Of the joint inspections, 73% were conducted in the U.S and 20% in the E.U. The median time from submission of an application to generation of final inspection reports was 232 days for FDA and 204 days for EMA, with no significant differences noted among applications with and without common sites.

Conclusion

The inspection processes and timelines between the two agencies were similar, providing support for continued FDA-EMA GCP collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

GCP inspections of clinical investigators (CI), sponsors and contract research organizations (CRO) in clinical trials are critical for regulatory assessments of new drug and biologics license applications at both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA). Prior to 2009, both agencies conducted separate GCP inspections for the same marketing applications (term used by FDA) or marketing authorization applications (term used by EMA) during regulatory assessments.

In 2009, FDA and EMA began collaborating on GCP inspection activities under a confidentiality agreement [1]. The collaboration was intended to better understand the GCP inspection operations and regulatory requirements of each agency and to allow for exchange of inspection findings given the increasing number of globalized clinical trials [2]. The collaboration includes bimonthly meetings to discuss the status and/or findings from inspections for shared applications, exchange inspection documents, and identify sites for potential joint or observational inspections. In joint inspections, representatives from both agencies are at the same site and conduct the inspection simultaneously, with each regulatory agency writing a separate inspection report. During a joint inspection, the two agencies share information and documents and collaborate on various aspects of the inspection. During observational inspection, both agencies are at the same site and one regulatory agency conducts the inspection while the other regulatory agency observes similarities and differences in inspection procedures. Each agency may also inspect a common site at separate time, termed sequential inspection, (i.e., each agency conducts a separate official inspection and writes a separate report) due to different timelines. The approach to collaboration and the ability to coordinate inspection planning depended on the timing of the submission to each agency. Differences concerning whether to inspect and what site (CI, sponsor, or CRO) to inspect, the locations of the inspections, and the various regulatory timelines of each agency also contributed to the ability of the two agencies to effectively collaborate in this initiative.

For this report, we examined inspection processes between the two agencies in GCP inspections and evaluated various performance characteristics that potentially impact coordinating inspection planning and exchange of information in this initiative.

Methods

Data Sources

Both FDA and EMA use several systems and databases to maintain inspection data related to marketing applications. FDA used the Document Archiving, Reporting, & Regulatory Tracking System (DARRTS), Compliance Program Information System (COMPLIS), and Enterprise Content Management System (ECMS—document repository). The EMA used the product information and application tracking system (SIAMED), and the inspections database (CorpGxP). FDA document the results and findings of a GCP inspection in an Establishment Inspection Report (EIR) and Clinical Inspection Summary while EMA document in an Inspection Report (IR) and Integrated Inspection Report (IIR).

Identification of Inspection Data and Analyses of Inspection Processes

Inspection data were obtained from the data sources maintained by each respective agency. We first identified the shared applications, defined as an application that the same clinical trial data were submitted to both FDA and EMA for marketing authorization by the same applicant. Shared applications from September 2009 through December 2015 were identified by reviewing meeting agendas and lists of documents that had been exchanged over the course of the FDA-EMA collaboration during the study period. For each of the shared applications identified, the number and type of sites inspected, location of inspected sites, and relevant timelines of inspection process milestones at each agency were examined and tabulated accordingly. Shared applications were further classified into those in which there were common sites inspected by FDA and EMA and those that did not share common sites. For those applications that had common sites, inspections were categorized as joint inspections that were conducted concurrently by both agencies, and sequential inspections that were conducted separately at different times by both agencies. For applications that had no common sites between the two agencies, the sites were designated “FDA Only” or “EMA Only”, as appropriate.

A mapping structure to determine the most logical method of comparing data between the two agencies was developed (Table 1). A data dictionary was developed to ensure that the identified timepoints were correctly labeled and cross-checked for the analysis. An inspection reference number was used to map each EMA inspection to its corresponding FDA inspection in FDA’s COMPLIS database. Once the attributes for analysis were identified, each agency extracted the respective data for each application and conducted several rounds of quality control using the applicable source documentation, including FDA’s EIR and Inspection Assignment Memo and EMA’s IIR and inspection announcement letter. EMA’s data was then imported into FDA’s COMPLIS database, and a report was generated to combine each agency’s corresponding inspection data for analysis.

Study Outcomes

We used descriptive statistics to tabulate the identified inspection characteristics and analyze timelines related to these characteristics (Table 2) between FDA and EMA. For applications that had two or more inspection assignments during the review course, relevant timelines were calculated based on the date of the first assignment, first inspection start, last inspection, and final inspection report regardless of the assignment sequence.

Results

General GCP Inspection Characteristics of the Shared Applications

Fifty-nine shared applications had GCP inspections by both FDA and EMA from September 2009 through December 2015. Four applications were excluded from the analysis. One application was refused to file by FDA after submission. Three other applications had trial data from different study protocols. For the 55 shared applications included in the analysis, a total of 433 GCP inspections were conducted in 47 countries across the globe (Fig. 1), with 45% in the U.S., 25% in European Union (E.U.), and 30% in other countries and regions outside the U.S and E.U. Of these inspections, 345 (80%) were for CIs and 88 (20%) for sponsors/CROs (Table 2). For the CI inspections, almost half conducted by FDA were located in the U.S. (103 out of 219, 47%) while about three quarters conducted by EMA were located outside of E.U. (95 out of 126, 75%). The median number of CI inspections per application was four for FDA and two for EMA, respectively. For the sponsor/CRO inspections, the majority of the inspections were conducted in the U. S. (Table 2).

Of all the inspections conducted, 31% were for marketing applications in oncology and hematology, 20% in cardiology, neurology, and nephology, 14% for in infectious diseases, 11% in endocrinology, and 24% in other disease areas (e.g., rheumatology, gastroenterology, urology, psychiatry, dermatology, and medical imaging).

Characteristics of GCP Inspections Conducted for Shared Applications with Common Sites

Twenty-eight out of 55 (51%) shared applications had 43 common sites inspected by both agencies. These included 23 CI sites and 20 sponsors/CROs (Table 3). This represents 20% of the total 433 inspections conducted by both agencies. Of the 43 common sites, 15 sites (ten CIs and five sponsors) had joint inspections conducted by FDA and EMA concurrently for seven applications; 28 sites (13 CIs and 15 sponsors/CROs) were inspected sequentially by both agencies for 21 applications. Most joint inspections were conducted in the U.S., with 70% (14 out of 20) for CIs and 80% (8 out of 10) for sponsors/CROs. Thirty one percent (8 out of 26, 31%) of sequential inspections for common CI sites were conducted in the US while most of common sponsor/CRO sequential inspections (22 out of 30, 73%) occurred in the U.S. (Table 3).

Characteristics of GCP Inspections Conducted for Shared Applications Without Common Sites

Twenty-seven out of 55 shared applications (49%) had no common sites inspected by both agencies. Of the total 347 inspections for these applications, 227 were conducted by FDA only and 120 by EMA only (Table 3). FDA conducted 104 (53%) CI inspections outside the U.S. versus 92 (47%) in the U.S., while EMA had 76 (74%) outside the E.U. and 27 (26%) in the E.U. US conducted the majority of sponsor/CRO inspections (84%) in the U.S. while EMA conducted about half (47%) in the U.S. (Table 3).

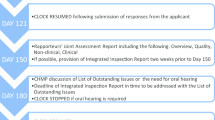

GCP Inspection Processes and Related Timelines

For all the shared applications, both agencies completed GCP inspections prior to taking regulatory actions. Overall, the time interval from the submission of the applications to generation of final inspection reports was similar between the two agencies, with a median time of 232 days for FDA and 204 days for EMA (Table 4). Compared between the applications with and without common sites, median times were also similar: 241 days with common sites versus 232 days without common sites for FDA; 208 days with common sites versus 197 days without common sites for EMA (Table 4).

Five key inspection process timelines were evaluated, and the results are listed in Table 4. Overall, median times spent for Selection of Inspection Entities after Submission (59 days for FDA and 36 days for EMA) and Completion of Inspections (47 days for FDA and 32 days for EMA) were slightly shorter for EMA, whereas median time for Initiation of First Inspection after Assignment (34 days for FDA and 59 days for EMA) was slightly shorter for FDA. Median times for Assignment to Field and Inspection Reporting after Last Inspection were highly similar between two agencies. For each agency, there were no notable differences in these sub-timelines between the shared applications with and without common sites.

Discussion

This is the first analysis of the GCP inspection process comparing timelines between FDA and EMA since the two agencies established GCP inspection collaboration in 2009. The results show that for the 55 shared applications, each agency conducted hundreds of GCP inspections across the world. Most of the clinical investigator inspections were conducted in regions outside of each agency’s respective regulatory territory, whereas most sponsor/CRO inspections occurred in the U.S. This probably was due to the fact that the shared applications were mostly global trials and the majority of sponsors/CROs were based in U.S. Twenty percent of the total inspections were performed by both agencies at the common inspection sites, either jointly or sequentially. In general, final inspection reports were completed approximately 7 months following submission of an application for both agencies. This result reveals that the overall GCP inspection process timelines (e.g., length of time from application submission to final inspection reporting) are not considerably different between the two agencies. For example, from the shared applications included in the pilot, the FDA took two to 3 weeks longer than the EMA to select inspection sites and complete inspections even though FDA initiated the inspections about 3 weeks sooner after assignments. This could be due to factors such as FDA generally conducted more CI inspections than EMA (four CI inspections for FDA versus two for EMA), and therefore, it took longer for FDA to complete all inspections.

The key limitation of this study is the small number of the shared applications identified during the study period. We examined only inspections conducted by the two agencies during the study period. This may not well reflect increasing GCP collaborative activities of the two agencies in more recent years. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of data collection and the fact that the analysis of these shared applications occurred in many cases, several years after application submission. This retrospective approach made it difficult to fully understand differences in the method by which each agency selected sites to inspect.

Overall, our study shed light on differences and similarities in GCP inspection process timeline between the two agencies for the inspections conducted for the shared applications between 2009 and 2015. The observed inspection timelines suggest that both agencies have similar GCP inspection processes. The minimal differences in timelines did not appear to affect the overall completion of GCP assessments by each agency.

Our recent study outlined the similarities and differences of GCP inspection findings from both agencies. The results showed that GCP inspection findings from common CI and sponsor/CRO inspections were comparable with respect to protocol compliance and trial management, providing support for continued FDA-EMA GCP collaboration [3].

FDA and EMA have existing programs in place to evaluate compliance with applicable regulatory requirements and GCP provisions [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Until 2009, these programs had neither included a bilateral, systematic coordination in conduct of GCP inspections for marketing applications of common interest nor developed a systematic and timely mechanism for sharing relevant GCP-related information.

Conclusion

The inspection processes and timelines between the two agencies were similar, providing support for continued FDA-EMA GCP collaboration. The similar timelines allow for more efficient use of finite resources, reduce duplicative inspections, and broaden inspection coverage by the two regulatory agencies. This is especially important when a shared application is submitted to both agencies around the same time, permitting for real time information sharing and collaborative inspections.

References

EMEA-FDA GCP initiative. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/compliance/good-clinical-practice. Accessed 17 May 2022.

EMA partners-networks. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/international-activities/bilateral-interactions-non-eu-regulators/united-states. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Sellers JW, Mihaescu CM, Ayalew K, et al. Descriptive analysis of good clinical practice inspection findings from U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-022-00417-w.

US Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Bioresearch Monitoring Program (BIMO) Compliance Programs. FDA’s Compliance Program Guidance Manual (CPGM). https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/compliance-program-guidance-manual-cpgm/bioresearch-monitoring-program-bimo-compliance-programs. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Directive 2001/20/EC OF the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/dir_2001_20/dir_2001_20_en.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Commission Directive 2005/28/EC of 8 April 2005 laying down principles and detailed guidelines for good clinical practice as regards investigational medicinal products for human use, as well as the requirements for authorization of the manufacturing or importation of such products. https://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:091:0013:0019:en:PDF. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0536&rid=2. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/556 of 24 March 2017 on detailed arrangements for the good clinical practice inspection procedures pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 536/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R0556&rid=1. Accessed 17 May 2022.

ICH Topic E6 (R1). Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-e6-r1-guideline-good-clinical-practice_en.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2022.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amir Tahami, M.B.A., for helping to extract FDA inspection information; Laurie Muldowney, M.D., Jean Mulinde, M.D., and David Burrow, Pharm.D., J.D. in the FDA’s CDER Office of Scientific Investigations for their review of the draft manuscript. The authors also wish to thank Fergus Sweeney, PhD, Head, Clinical Studies and Manufacturing Taskforce, European Medicines Agency for his review of the draft manuscript. We thank all GCP inspectors from EU member countries and FDA investigators from the Office of Regulatory Affairs (Office of Bioresearch Monitoring Operations) for the inspections they conducted on behalf of EMA and FDA, respectively.

Funding

No financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the agencies or organizations with which the authors are affiliated. Of note, Dr. Khin contributed to this work while she was an employee of the US Food and Drug Administration. Dr. Khin reported she is currently employed by Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. In addition, Agata Higgerson contributed to this work while she was an employee of the European Medicines Agency (EMA), Dr. Higgerson reported she is currently employed by Roche.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayalew, K., Ning, YM., Foringer, M.J. et al. Comparison of Good Clinical Practice Inspection Processes for Marketing Applications Between the United States Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency. Ther Innov Regul Sci 57, 79–85 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-022-00441-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-022-00441-w