Abstract

An ageing population is a universal phenomenon experienced worldwide. In parallel with these demographic changes, a significant breakthrough in digital devices has also influenced this digital age. Designing instructional strategies to promote meaningful learning among older adult learners has been a long-standing challenge. To enhance older adults’ life-long learning experiences, implementing instructional strategies in the process through which such adults learn can help to improve effective learning. Despite significant calls for research in this area, there is still insufficient research that systematically reviews the existing literature on older adult learning needs and preferences. Hence, in the present article, a systematic literature review was conducted of the effectiveness of instructional strategies designed for older adult learners through the use of digital technologies. The review was guided by the publication standard, which is ROSES (Reporting Standard for Systematic Evidence Syntheses). This study involves articles selected from two established databases, Web of Science and Scopus. Data from the articles were then analysed using the thematic analysis, which resulted in six main themes: (1) collaborative learning; (2) informal learning setting; (3) teaching aids; (4) pertinence; (5) lesson design; and (6) obtaining and providing feedback. The six main themes produced a further 15 sub-themes. The results from this study make significant contributions in the areas of instructional design and gerontology. The findings from this study highlight several important strategies of teaching digital technology, particularly for older adults, as follows: (1) to enhance instructional design use in teaching digital technology based on the needs and preferences of older adult learners; and (2) to highlight the factors for, and impact of, learning digital technologies among older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the United Nations (2017), the number of adults over the age of 60 will, for the first time ever, surpass that of children aged 0–9 years by 2030 [44]. In view of the ageing world population, extensive attention has been given to improving the quality of life of older adults [38]. In 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that active ageing may be achieved through three distinct determinants, namely health, security, and participation. Lai [22] noted that educational intervention has been found to be among the best and effective approaches to help elderly adults participate in, and engage with, society, allowing them to enjoy a more positive and higher quality of life. Psychological changes, especially declines in various cognitive abilities, are highly correlated with ageing [2]. This can cause older adults to encounter difficulties and hardships when dealing with interfaces that involve shifts related to ageing, such as the loss of control over movement, perception, and even cognition [23, 25].

According to Jefferson (2019), the users of technology among people in the older adult’s category in the current years have risen quite a lot which is 73%, compared to only 14% in the year 2000. With the engagement of older adults and the use of information communication technology (ICT), the quality and wellbeing of their lives could be enhanced. However, older adults continue to lag behind and are comparatively slower than younger groups in their use of ICT terms. Despite the strategies and approaches to equipping older adults with technology skills and enhancing their digital literacy, their relationship with the adoption of technological skills is not straightforward [44]. Previous studies by Boulton-Lewis, Buys, Lovie-Kitchin, Barnett and David [6], Erickson and Johnson [12], and Heo, Chun, Lee, Lee, and Kim [18] mentioned the advantages that the usage of ICT tools had on the psychological wellbeing and quality of life of older adults.

Currently, updated technologies can improve the autonomy and quality of life of older adults by giving them opportunities to create and maintain social relationships, obtain access to care and services and enhance their life-long learning programmes, as well as enjoy and entertain themselves [9, 13, 20, 42, 43, 48, 49]. Though the acceptance of technological devices has greatly improved among older adults, most of them tend to use the limited range of functions that they are familiar with, as they have not fully grasped the benefits of the technological item overall [22]. Lai added that adult educators should be alerted to providing educational activities for this group of people, as an effort to educate them on the usage of mobile devices may improve their quality of life.

Most older adults possess positive views of technological items and mobile devices, so they are likely to engage with these items [4]. A discussion among IT professionals and educators arose as they assessed the kinds of skills and knowledge needed by someone living in the twenty-first century [5]. Older adults need enhanced encouragement to spur them to participate in the process of learning new technologies and to use them continually [22]. According to Muñoz-Rodríguez, Hernández-Serrano, and Tabernero [28], digital identity building and development must be considered if advanced technologies are likely to be able to provide viable learning opportunities and improve the ability to maintain life-long learning. Associating active ageing with the growing possibility of learning technologies means challenging didactics to achieve life-long learning for older adults and to allow them to continue learning throughout their lives [28, 33]. Various research has been developed that focuses on the increased access to technologies among older adults [20, 27, 46, 47]; older adults’ engagement with digital technologies [28, 29, 45]; and even how wealth, health, and social relations are advancing due to the implementation of ICT [21, 39]. Though guidelines on designing technology for older adults exist, a few studies have investigated the ability of older adults to learn different aspects of technology and the techniques that can be used to enhance the process of learning digital technologies [1].

Research Gap

The existing studies relate to the effectiveness of instructional strategies designed for older adults in learning digital technologies. Although many studies discuss this issue, there remained an insufficient number of systematic reviews of the existing studies. Through a systematic review, precise questions were developed to help produce relevant evidence. A search was performed using precise key terms within specified databases and a data extraction tool was used to identify precise information. Meanwhile, a traditional literature review is exposed to several reliability and quality issues [36]. This paper attempts to contribute to the body of knowledge by developing a systematic literature review of the effectiveness of instructional strategies designed for older adults in learning digital technologies. The systematic process was used throughout and proper protocol was specified before the review process. In a systematic literature review (SLR), the study used a rigorous search strategy that enabled the researchers to answer a defined question [50]. Even though some studies have attempted to systematically review the effectiveness of instructional strategies for older adults in learning digital technologies, they only focus on specific technologies, such as games, web, and electronic services or the use of smartphones, while this study focuses on the use of digital technologies in general. A study by Shi et al. [40], for instance, focused on specific e-Health usage among Chinese older adults. The lack of studies on the effectiveness of instructional strategies for older adults in learning digital technologies has resulted in a lack of understanding and failure to comprehend the related existing literature in a systematic way.

This study offers several significant theoretical and practical contributions to researchers in the fields of gerontology and education, practitioners, and even educators. The instructional strategies identified in this review could be used as a guide for researchers seeking the best approach to encourage the use of digital technologies among older adults. This study also highlights several factors and impacts of the positive aspects of the use of digital technologies among older adults.

Methodology

The Review Protocol: ROSES

This study was conducted following the ROSES guide, that is, Reporting Standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses, which was specifically designed for systematic reviewing and mapping in environment management [15]. The aim of the ROSES protocol is to aid researchers by ensuring that the information they provide in their papers is written precisely and with the right details. Based on the ROSES review protocol, the SLR began with the formulation of an appropriate research question that fits the review conducted. The systematic search strategy consisted of three sub-processes, known as identification, screening (which involves the inclusion and exclusion criteria), and eligibility; these are explained in detail. The next step was the quality process appraisal, in which the author would explain and elaborate on the strategy that was used to evaluate and ensure the quality of the articles shortlisted from the processes before they were reviewed. In the last step of the methodology, the author explains the methods used when abstracting the data from the articles and how the data abstracted were analysed and validated.

Formulation of Research Questions

The research questions for this study were formulated based on PICo, a tool commonly used to formulate and establish relevant and fitting research questions for reviews. PICo stands for Population or Problem, Interest and Context and represents the main concepts. When the concepts had been ascertained, the main conditions in this review were identified and assigned to the respective concepts: older adults (population), instructional strategies and older adults’ learning (interest), and digital technologies (context). From the designation, the research question was developed: “Do instructional strategies enhance older adults’ user experience in learning digital technologies?”.

Systematic Search Strategy

The three main processes of the systematic search strategy—identification, screening, and eligibility—are as shown in Fig. 1.

Identification

This process began with the search for synonyms, related terms, and variations of the main keywords, which for this study were instructional strategies, older adults, elderly learning, and digital technology. The aim of varying the terms was to provide multiple options that the selected databases could use to detect more corresponding articles and not limit them only to the set of keywords. The development of keywords based on the research questions was suggested by Okoli [31]. This process was conducted with the aid of an online thesaurus and keywords that were suggested by experts. Through the varying process, existing keywords were diversified and developed into string searches, with Boolean and/or operator, truncation and wildcards embedded in the search. The string searches were conducted on the databases selected, which were Web of Science and Scopus (Table 1). According to Martín-Martín et al. [26] and Gusenbauer and Haddaway [14], both Web of Science and Scopus are renowned to be the leading databases commonly used in systematic literature reviews. This is because they contain certain advantages: they have advanced search functions, the findings are extensive (as they contain over 5000 publishers), and the databases control the quality of the articles and contain multidisciplinary resources. The search process involving these two databases resulted in a total of 978 articles.

Screening

In the screening stage, all 978 articles were screened by selecting the articles selection criteria appropriate in the current study. This first screening step was performed automatically by the databases’ systems once the criteria had been selected by the sorting function available within the database interface. Kitchenham and Charters (2007) suggested that the research question should be one of the selection criteria. Since it would be almost impossible to review all the existing articles, Okoli [31] suggested that researchers determine the period range covering the publication dates of articles that authors would review, while according to Higgins and Green [19], a publication timeline restriction could be used only if it is known that related studies could only have been reported during a specific time period. According to the findings from the database, numerous studies that correlate to older adults’ learning digital technology were published from 2017 onwards. In this paper, the search process began in April 2021, and since the year has yet to end, this explains the reason for limiting the searches to 2021. Therefore, one of the inclusion criteria for the articles to be reviewed was articles must fall within a timeline between 2017 and 2021 (Table 2). Next, to ensure the quality of reviews, only publications in the form of articles were included. This meant other types of publications were excluded from the article selection criteria. Furthermore, only articles published in English were incorporated in the review to avoid mistranslations, confusion, and misunderstandings. Meanwhile, the subjects of the articles were also limited to interdisciplinary social sciences, education educational research, geriatrics gerontology, linguistics, and communication. Through this process, 882 articles were excluded from the initial list of 978 articles as they did not fit the criteria. Another aspect of the screening process is detecting duplicate articles. Since articles were obtained from two different databases, some articles would be present in both, so duplication of articles may occur. Twenty-five articles were excluded as they were duplicates, leaving 71 articles that were used for the third process, eligibility.

Eligibility

The third process of the systematic search strategy is eligibility, in which the retrieved articles are reviewed manually by the author to ensure the articles that passed the screening process fit the criteria determined earlier. Eligibility was conducted by reading and analysing the article titles and abstracts. Fifty articles were excluded as they were overly focused on health technology rather than general technology, focused on the development of technology rather than learning how to use technology, centralised on general learning and not older adults’ learning, or unrelated to elderly people learning through digital technology.

Quality Appraisal

Two experts coordinated the quality assessment to ensure the content quality of the eligible articles. According to Petticrew and Roberts [35], experts should be responsible for ranking eligible articles into three respective qualities which are high, moderate, and low. Once the rankings had been determined, only articles from the highest rank should be reviewed in the study. The experts focused on the article methodologies to determine the rank of the quality. Both experts must mutually agree that an article should be at least in the moderate rank for it to be included in the review. Any disagreements arising during the article inclusion and exclusion process were discussed among the review authors. In this process, 14 articles were ranked as high and the remaining three were ranked as moderate. In conclusion, all 17 articles were legitimately eligible for the review.

Data Abstraction and Analysis

In the present study, the process of identifying, analysing, and reporting sub-themes was based on thematic analysis, also known as qualitative analysis techniques, developed by Braun and Clarke (2006). The first step of the thematic analysis requires researchers to immerse themselves in the data obtained by conducting repeated reading in an active manner in order to capture meanings and patterns. The second step is to generate and create initial codes. This is done by extracting related data from the eligible articles and organising the data into respective meaningful groups, in which the text is dissected into segments according to word, phrase and/or sentence. This process managed to identify a total of 200 initial codes. Once the initial codes have been identified, the next process, is the ‘peer debriefing’, in which the initial codes are sent to co-authors to be verified, so bias can be avoided during the data interpretation process. The authors then correct and amend the initial codes by renaming, removing, and re-writing new initial codes, as advised by the peer panel. After the peer debriefing, the next step is to search for sub-themes. This stage requires the researcher to analyse all the sub-themes that had been derived from the previous initial codes. From the process, 15 sub-themes were identified. The search for the themes involves the process of sorting the different sub-themes previously gathered and collating relevant sub-themes within the identified themes. This resulted in six themes created from the selected articles. Once the process is completed, the identified sub-themes and themes must go through verification by an expert panel. Expert panels are appointed from among qualitative experts who have over 5 years of experience in conducting qualitative research. The experts were asked to evaluate the 6 themes and 15 sub-themes. Results are considered final once the themes and sub-themes have been agreed upon by both experts.

Results

Background of the Selected Articles

This study obtained 17 eligible articles from two prominent databases, World of Science and Scopus. Based on the thematic analysis conducted, six themes were developed. The themes consist of: collaborative learning, informal learning setting, teaching aids, pertinence, lesson design, and obtaining and providing feedback. Subsequently, further analysis of the data resulted in 15 sub-themes. Based on the total of 17 selected articles, seven studies were conducted in the United States; Spain, China, and Canada contributed two studies each; while one study came from Greece and one from Australia. Two of the selected studies were conducted in multiple countries, including Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, The Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovak Republic, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Slovenia, and Austria. Out of the 17 selected articles, one paper was published in 2021, three were published in 2020, six papers were from 2019, four papers were from 2018, and three papers were published in 2017. The age range of the respondents for all 17 studies fell between 54 and 100 years.

The Themes and Sub-themes

Collaborative Learning

A collaborative learning strategy is defined as a situation in which two or more people learn or try to learn something together [16]. Under this theme, this study obtained five sub-themes. The first theme was engagement. In a study held in the United States by Dauenhauer, Heffernan, and Cesnales [10], engagement occurs during learning using technology within small and large group discussions and also when older adult learners collaborate with younger learners in course assignments. Engagement in learning promotes social relationships between the learners and exchanges of knowledge; in another study by Olivares-Cuhat (2018), the implementation of methods, such as online quizzes; tutorials, blogs, wikis, chats, and instant messages and the use of interactive lessons. A further method was the provision of the scope for virtual and physical interactions among older adult learners and their peers to focus more on learning using digital technologies. Another study highlighted the use of the gameplay concept, which kept older adult learners engaged and focused while building self-confidence and enhanced their knowledge when learning with digital technology [37].

The second sub-theme is participation. Older adults tend to perceive significance when learning digital technology through activities that promote collective interactions and those that allow the learners to feel linked to each other [28]. The participative learning environment stimulates creativity, negotiation, and social understanding between older adult learners. Digital technology often allows older adult learners to share information, give their opinion, keep up to date, and have the opportunity to try using the Internet [42]. In a study by Olivares-Cuhat (2018), the preferred opportunities for interaction among the elderly are those that allow online content sharing on an online learning platform. This method allows older adult learners to participate with peers and interact effectively.

The third sub-theme is cooperative learning. The involvement of teachers and peers in learning digital technologies encourages cooperative actions among older adult learners [34]. The aforementioned study shows that although older adults are initially reluctant to seek help from others, they tend to make mistakes and, at some stage, eventually need support from others. Therefore, the study by Muñoz-Rodríguez et al. [28] mentioned that the design for online environments used by older adult learners should be a catalyst for collective cooperation, so they can feel linked to others. This feeling is important for older adult learners, as a study by Tyler et al. [44] highlights. One method of achieving this feeling is to establish a community group to boost motivation, which provides social as well as technical support in learning digital technologies. Through an exit survey in a study by Chen et al. [8], older adult learners indicated that they enjoyed learning in a group format as opposed to an individual format. Therefore, learning in settings, such as training, small discussion groups [17], or workshops, has been recommended for older adult learners, since they need help to explore technologies and facilitate their learning process [42]. Furthermore, using technology in a group discussion setting fosters an encouraging and cooperative environment, which further contributes to the leisure experience among older adult learners [11]. Dove and Astell [11] conducted a study focusing on older adult learners with dementia or MCI using motion-based technology in a group setting. Cooperation among all learners occurred within small and large group discussions and they were also able to exchange knowledge [10]. Several scholars, for instance, Blažič and Blažič [5] and Seah et al. [37], have emphasised that learning in a gameplay environment establishes communication and encourages cooperation between all learners.

Although collaborative learning and cooperative learning hold the same concept where it basically requires the learners to learn together, there are some features that differentiate these two learning methods. According to Surbhi (2021), collaborative learning is where the learners act on their own initiative to work together with their peers, and they take charge of their own learning session with each other. Cooperative learning on the other hand is where the learners are assigned by their instructors to work together, where the tasks and activities are provided and assigned to the group of learners, which makes it an instructor-structured learning method. Myers (1992) as cited by Panitz (1999) stresses the definition of collaboration where it focuses on the process of joint effort among learners in sharing the knowledge among each other. As for cooperative learning, it enhances the cooperation among learners to complete a given task to achieve a specific outcome, as requested by the task giver, usually the instructors.

The fourth sub-theme is known as intergenerational learning. Intergenerational learning happens in a learning situation that involves people from two or more different generations. A study by Lee and Kim [24] stressed that intergenerational learning is important for older adult learners, since it can decrease their anxiety about technologies and boost their confidence. Pappas et al. [34] revealed that the level of education of older adults plays a significant role in their attitudes to learning using digital technologies, whereby better-educated learners are more confident compared to older adults with a lower educational level. Therefore, learning with the assistance of family members or grandchildren helps older people considerably in gaining an interest and confidence in the use of digital technologies [22]. It might also allow the exchange of insights across generations [10].

The last sub-theme is mentoring. Older adult learners learn using digital technologies slowly, compared to younger learners [7]. However, technologies help older adults overcome health and isolation problems [24]. Older adult learners need a mentor’s assistance in using digital technologies, which includes providing step-by-step guidance, manual help [44] and support, especially concerning technical aspects [22]. In addition, older adult learners should occasionally be provided with clear explanations by mentors of how to operate digital technologies [8]. In fact, another study stressed the need to conduct a training programme that was specially designed for older adult learners and provided with several mentors who could facilitate the learning process [42], as older adults need additional attention. It is difficult for older adult learners to use devices like smartphones, for instance, so they need mentors in their educational sessions to help them adopt digital skills [5].

Informal Learning Setting

An informal learning space is a type of setting that has been designed to promote independence and freedom, so that learners are comfortable when they learn and gain knowledge [3]. There are two sub-themes under this theme, namely experience-based learning and personalised learning. The first sub-theme is experience-based learning. Older adult learners enjoyed learning by sharing their experiences and opinions [8, 10]. They prefer an experience-based learning approach in an active environment, for instance, using an online learning platform, so that they can share their life experiences, opinions, and expectations with different generations of learners [10, 17, 34, 44].

The next sub-theme is personalised learning (Table 3). Outcomes from various studies reveal that older adult learners need a flexible curriculum design, so they can follow lessons at their own pace [8, 34]. Besides, older adult learners need an informal learning setting with a personalised curriculum, so that their digital learning sessions are more effective [30]. Several studies emphasise that implementing individualised training for older adult learners can be a practical solution as it encourages them to learn using digital technologies [8, 22, 24]. Some older adult learners face the problems of anxiety and a lack of confidence in learning digital technologies [24]. They should be encouraged to learn using mobile phones. To add interest, an in-person training session [8] could be held outside the classroom setting, for instance, in a library, fitness centre, or dining hall/cafe [10].

Teaching Aids

As cited by Yasim et al. [51], the use of teaching aids can improve the effectiveness of teaching and learning and improve knowledge and skills, and it should complement teaching methods that are constantly changing. A total of three sub-themes emerged under this theme, which are audio-visuals, reading materials, and game-based aids. The first sub-theme is audio-visuals. Previous research has highlighted that the use of explanatory videos in learning digital technologies is effective in maintaining the attention of older adult learners [17, 41]. In fact, live videoconferencing is useful as it allows live discussions between instructors and learners in some situations [17]. Videos should have large text and clear iconography to enhance clarity [8].

The second sub-theme is known as reading materials. Modules provided to older adult learners can include simple graphics but not bright colours or excessive graphics [34]. It has also been recommended to provide pictorial handouts as a means of support for older adult learners who may be less skilled in using digital technologies [10]. To motivate older adult learners, the handouts should use bold characters or colours in the content, while each image should be supported with narration [32], but should not contain a lot of text [34]. Written instructions in the handout should also be provided in easy-to-understand documents, so that the desire of older adult learners to technological tools could increase [22]. Irrelevant content should be avoided as it can distract older adult learners’ focus, while words and pictures should be presented within the same spatial area [32].

The third sub-theme in the teaching aid’s theme is game-based aids. Learning digital technologies by playing games is seen as an effective strategy for older adult learners. Playing games through learning digital technologies has kept players engaged and relaxed, and has created fun experiences for them [5, 37]. Moreover, positive experiences during game-playing help older adult learners to learn digital technology more quickly and successfully, eventually leading to faster digital skills adoption [5]. Meanwhile, a study by Dove and Astell [11] shows that older adult learners with dementia are also able to learn Kinect technology through playing games. Game-based learning among older adult learners could help improve their wellbeing [37].

Pertinence

Pertinence, otherwise known as relevance, is crucial when holding a teaching and learning process, especially for elderly learners. This is because the elderly are likely to want to participate in the learning process if they find the content and skills relevant to their needs in life. One sub-theme is identified in this theme, namely relevance to needs. In terms of learning digital technologies, older adult learners prefer that the digital lesson is practical and relevant to their daily needs [32, 37]. It is important to outline the roadmap of the training or learning session at the beginning to provide a clear rationale for learning digital technologies [8]. More attention is needed in designing digital training sessions, so that the session is tailored to the needs of older adults [5]. Furthermore, choosing the correct digital technologies is important, since older adults are particular about what they can gain from a digital learning activity [37].

Lesson Design

When designing a lesson for a course, it is crucial for the instructor to pay attention to the learners, as the purpose of a lesson is to deliver knowledge to those receiving the course. Lesson design incorporates the methods and strategies that will be used, preferably those which can cater to the learners’ needs. In this study, the lesson design refers to the methods implemented during the course, which are repetition and the learners’ time preferences. There are two sub-themes under this theme, which are repetition and time preference. The first sub-theme that will be addressed is repetition. A study by Dove and Astell [11] highlighted that repetition strategies have been found to be effective for older adult learners with dementia problems, since repeated exposure to digital technologies and games enables learners to master certain digital skills. Repetition strategies in learning digital technologies function as memory aids the teaching sessions of older adult learners [32].

Another sub-theme under lesson design is time preference. There is evidence that older adult learners can learn digital technologies as younger people do; however, they might need extra time to reach the mastery level [7]. Older adult learners show positive attitudes to learning digital technologies as they may attend longer training sessions [24] and be willing to spend longer time learning, especially to explore the Internet [42]. Research has highlighted that older adult learners tend to prefer daytime class to class at night due to their inability to drive at night [10].

Obtaining and Providing Feedback

The last theme identified in this study is obtaining and providing feedback. Feedback can be obtained in the form of assessment results. This means that the results of any assessment given by the instructor to the learners serve as a type of feedback to identify whether the instructional strategy used during the lesson was effective or not. Two sub-themes emerged under this theme, feedback and assessments. The first theme is feedback. Feedback is needed by all learners, including older adults, so they can obtain a response to their knowledge and ability in learning digital technologies [37]. Feedback creates an active learning environment and cultivates an experience-based learning approach for older adult learners [34]. They prefer to receive feedback but not necessarily to be marked by the instructor [34]. Feedback can also be provided in the form of a game-based approach [37]. The second theme is assessments. Assessment is emphasised as an important strategy in older adult learning. The educational content of each digital technology course should contain exercises and assessments at the end of the learning session [34]. From these assessments, older adult learners may understand their ability and knowledge of what they learnt in terms of digital technologies. Meanwhile, learners can use assessments to focus on mastering their digital skills weaknesses [37].

Discussion

The thematic analysis generated 6 themes and 15 sub-themes. This section of the paper provides further discussion of the themes that had been developed. The first theme, collaborative learning, emphasises that integration and togetherness can occur during a lesson. This could be achieved through instructors enhancing the learners’ engagement during a particular lesson [10, 32]. Two of the eligible articles mentioned how encouraging engagement helps make a course more effective [10, 32, 37]. Encouraging learners to participate in any activities that are being conducted during lessons also helps the learners receive the lesson content more successfully. A participative learning environment can stimulate creativity, negotiation, and social understanding among older adult learners [42]. This method allows older adult learners to participate with their peers and interact effectively (Olivares-Cuhat, 2018). Cooperative learning, an aspect of collaborative learning, shows how learning with each other and cooperation among learners can be implemented as strategies that make learning more effective. This is because learning with each other enables learners to feel far more comfortable as they are able to exchange their knowledge and insights [10]. Older adult learners enjoy sharing their opinions, which might also be useful in the lives of others [8]. Intergenerational learning is an effective instructional strategy as people from different generations get to share their respective knowledge and exchange it among themselves. Learning with different generations of learners is important, since it can reduce older adults’ anxiety about technology and boost their confidence [24]. Assistance from family members, such as grandchildren, could increase older students’ interest and confidence in using digital technologies [22]. Mentoring is another aspect of collaborative learning. In this context, mentoring could mean an instructor mentoring learners, or even friends or peers mentoring each other. Older adult learners need assistance from mentors in using digital technology, including providing step-by-step guidance, manual help [44] and support, especially concerning technical aspects [22]. It can be difficult for older adult learners to use digital technology, in which case they need a mentor to explain how to operate the technology [8]. This reveals how collaborative learning functions.

The next theme identified through the analysis is the informal learning setting. As mentioned earlier, learning in an informal setting may help students to learn more comfortably. This may be enabled by implementing experience-based learning and personalised learning that best fits the personality preferences of the learners. Older adults have extensive life experience and knowledge and they particularly enjoy sharing their experiences and opinions [8, 10]. In fact, they prefer learning digital technologies in an active environment, so that they can share opinions and expectations with other learners [10, 17, 34, 44]. Older adult learners also need an informal learning setting with a personalised curriculum, so that their digital learning is more effective [30]. The individualised training approach has been found to be effective among older adult learners as it encourages them to learn digital technologies [8, 22, 24].

As mentioned earlier in the results section, the use of teaching aids during a lesson can improve the effectiveness of teaching and learning, besides improving the knowledge and skills and complementing the teaching methods. One type of teaching aid that can be used when teaching elderly learners is audio-visual aids. The inclusion of appropriate reading materials can also help arouse elderly learners’ interest in learning [34]. Moreover, the integration of games may also help improve the effectiveness of a lesson [11]. It is known that people tend to face cognitive decline as they grow older, besides developing a shorter attention span and only being able to focus for a short time. The use of these kinds of aids may help elderly learners to focus and become more immersed during their lessons.

One of the most important strategies to implement for the lesson is pertinence. Pertinence refers to the content relevancy, that is, whether it is relevant to learners’ needs, who, in this case, are older adult learners. Some members of the elderly population tend to be reluctant to learn something that does not interest them and that they consider unnecessary, as they have passed the ‘survival’ era and are now in retirement [37]. This shows how relevancy is crucial in ensuring the lesson is effective for elderly learners. Before conducting a lesson, great attention should be paid to the lesson design stage [5, 8]. This is crucial as it highlights the strategy that is used with the learners, which must be selected according to whether it caters to the learners’ needs and suits the learners’ comprehension abilities. This review found that repetition was a common practice when dealing with elderly learners. This is because, as mentioned earlier, they experience cognitive decline, so repetition may help elderly learners remember more effectively [11]. Time preferences are also important, as it is necessary to consider the time frame the learners require to gain adequate knowledge. There is evidence that older adult learners can learn digital technologies as younger people do; however, they might need extra time to reach the mastery level [7]. They are willing to spend a longer time learning about digital technology, such as how to explore the Internet [42].

Finally, an important strategy to be implemented is obtaining and providing feedback among learners and instructors. This is essential as it helps both parties, the instructors and the learners. For instructors, giving assessments means the effectiveness of the strategies implemented during a lesson can be identified through the responses delivered by the learners. For the learners, receiving assessment means that they can personally identify and recognise the areas in which they are lacking and need more practice. Feedback for older adult learners can be provided in the form of a game-based approach [37] and not necessarily marked work from the instructor [34]. Meanwhile, the educational content of each digital technology course should contain exercises and assessments at the end of the learning session [34], so that older adult learners may ascertain their ability and knowledge of what they learnt in terms of the digital technologies. Meanwhile, learners can use assessments to focus on mastering their digital skills’ weaknesses [37].

Recommendations

Some recommendations are suggested for future scholars to take into consideration. The first suggestion is that more studies related to instructional strategies for older adult learning are needed as the number of older adults is rapidly increasing, as is the development of technological items that surround everyone today. It is crucial to find appropriate instructional strategies that effectively impact learning within the older adult group, as they can be adapted and adopted as part of the learning process. The systematic review process revealed that using digital technologies can help older adults to increase their socialisation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, older adults have experienced prolonged periods of isolation and have been prohibited from being outside and meeting outsiders or even relatives. Due to these restrictions, older adults may suffer from negative health effects, such as isolation and loneliness. Therefore, further investigation on the most suitable instructional strategies for learning digital technologies among older adults is vital to ensure their wellbeing, especially during the pandemic. Based on the review, most existing studies have focused on the positive factors and impacts of learning digital technologies among older adults, so the addition of any negative aspects could provide an overview in the form of guidelines for instructional strategies among older adults (refer to Fig. 2).

Conclusion

The aim of this paper is to systematically review how instructional strategies enhance user experiences of older adults in learning digital technologies. This study reviewed multiple instructional strategies from eligible articles that studied certain instructional strategies that had been implemented in the process of older adult learning. The study offers several significant contributions for practical purposes and to the body of knowledge. By referring to the systematic search strategy, which included the process of identification, screening, eligibility, and quality appraisal, 17 articles were eligible to be analysed. This resulted in the development of six themes with 15 sub-themes. After thorough reading and review, it has been determined that various strategies are needed to ensure the effectiveness of lessons that involve older adult learners. This includes a collaborative learning strategy, which could involve small or large group discussions, activities that promote collective interaction, or training and workshop settings. Intergenerational learning for older adult learners is also important, since it can reduce older adults’ anxiety about technology and perhaps offer exchanges of insights across generations. A collaborative learning environment promotes social relationships between the learners, stimulating creativity, and exchanges of knowledge. Older adult learners prefer the experience-based learning approach in an active environment, so that they can share their life experiences, opinions, and expectations. They need an informal learning setting with a personalised curriculum, so that their digital learning session is more effective. To add interest to the digital technologies learning session, explanatory videos, reading materials, or game-based strategies are effective ways to maintain the attention of older adult learners. When learning digital technologies, older adult learners prefer that a digital lesson is practical and relevant to their daily needs. Therefore, it is important to provide a roadmap of the learning session at the beginning. Most older adults suffer from cognitive problems due to the ageing process; therefore, teaching techniques must be repeated. Besides, older adult learners might need extra time to reach the mastery level. To find their ability and knowledge in terms of learning digital technologies, instructors must provide assessments at the end of the learning session. Feedback from instructors is also an essential strategy as it provides useful responses about older adults’ knowledge and ability in learning digital technologies. Older adults prefer to receive feedback but not necessarily be marked by the instructor, while feedback could also be provided through a game-based approach.

References

Antona M, Ntoa S, Adami I, Stephanidis C. User requirements elicitation for universal access. In The universal access handbook, 2009;pp. 1–14.

Baudouin A, Clarys D, Vanneste S, Isingrini M. Executive functioning and processing speed in age-related differences in memory: contribution of a coding task. Brain Cogn. 2009;71(3):240–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.007.

Berman N. A critical examination of informal learning spaces. High Educ Res Dev. 2020;39(1):127–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1670147.

Betts LR, Hill R, Gardner SE. “There’s Not Enough Knowledge Out There”: examining older adults’ perceptions of digital technology use and digital inclusion classes. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(8):1147–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464817737621.

Blažič BJ, Blažič AJ. Overcoming the digital divide with a modern approach to learning digital skills for the elderly adults. Educ Inf Technol. 2020;25(1):259–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09961-9.

Boulton-Lewis GM, Buys L, Lovie-Kitchin J, Barnett K, David LN. Ageing, learning, and computer technology in Australia. Educ Gerontol. 2007;33(3):253–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270601161249.

Calvo I, Elorriaga JA, Arruarte A, Larrañaga M, Gutiérrez J. Introducing computer-based concept mapping to older adults. Educ Gerontol. 2017;43(8):404–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2017.1309635.

Chen AT, Chu F, Teng AK, Han S, Lin SY, Demiris G, Zaslavsky O. Promoting problem solving about health management: a mixed-methods pilot evaluation of a digital health intervention for older adults with pre-frailty and frailty. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721420985684.

Cotten SR, Ford G, Ford S, Hale TM. Internet use and depression among older adults. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28(2):496–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.10.021.

Dauenhauer JA, Heffernan KM, Cesnales NI. Promoting intergenerational learning in higher education: older adult perspectives on course auditing. Educ Gerontol. 2018;44(11):732–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2018.1555358.

Dove E, Astell A. The kinect project: group motion-based gaming for people living with dementia. Dementia. 2019;18(6):2189–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217743575.

Erickson J, Johnson GM. Internet use and psychological wellness during late adulthood. Can J Aging. 2011;30(2):197–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000109.

Gilhooly MLM, Gilhooly KJ, Jones RB. Quality of life: conceptual challenges in exploring the role of ICT in active ageing. Assist Technol Res Ser. 2009;23:49–76. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-58603-937-0-49.

Gusenbauer M, Haddaway NR. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11(2):181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378.

Haddaway NR, Macura B, Whaley P, Pullin AS. ROSES Reporting standards for systematic evidence syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ Evidence. 2018;7(1):4–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-018-0121-7.

Hanid MFA, Mohamad-Said MNH, Yahaya N. Learning strategies using augmented reality technology in education: meta-analysis. Univers J Educ Res. 2020;8(5 A):51–6. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081908.

Hansen RJ, Talmage CA, Thaxton SP, Knopf RC. Enhancing older adult access to lifelong learning institutes through technology-based instruction: a brief report. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2020;41(3):342–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2019.1618852.

Heo J, Chun S, Lee S, Lee KH, Kim J. Internet use and well-being in older adults. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18(5):268–72. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0549.

Higgins JP, Green S. 2011 - Cochrane Systematic Reviews.pdf, 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/

Hunsaker A, Hargittai E. A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media Soc. 2018;20(10):3937–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818787348.

Ihm J, Hsieh YP. The implications of information and communication technology use for the social well-being of older adults. Inf Commun Soc. 2015;18(10):1123–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1019912.

Lai HJ. Investigating older adults’ decisions to use mobile devices for learning, based on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Interact Learn Environ. 2020;28(7):890–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1546748.

Lee C, Coughlin JF. Older adults’ adoption of technology: an integrated approach to identifying determinants and barriers. J Prod Innovat Manag. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12176.

Lee OEK, Kim DH. Bridging the digital divide for older adults via intergenerational mentor-up. Res Soc Work Pract. 2019;29(7):786–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731518810798.

Lee YL. The technologizing of faith: an ethnographic study of Christian University students using online technology. Christ Educ J. 2013;10(1):125–38.

Martín-Martín A, Orduna-Malea E, Thelwall M, Delgado López-Cózar E. Google Scholar, web of science, and scopus: a systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J Informet. 2018;12(4):1160–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.09.002.

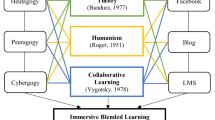

Mohd Zaid NN, Pek LS, Ahmad NA. Conceptualising digital-based instructional strategies for elderly learning. St Theresa J Hum Soc Sci. 2021;7(2):29–44.

Muñoz-Rodríguez JM, Hernández-Serrano MJ, Tabernero C. Digital identity levels in older learners: a new focus for sustainable lifelong education and inclusion. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2020;12(24):1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410657.

Navarro-Prados AB, Serrate-Gonzalez S, Muñoz-Rodríguez JM, Díaz-Orueta U. Relationship between personality traits, generativity, and life satisfaction in individuals attending University Programs for seniors. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2018;87(2):184–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415017740678.

Nygren H, Nissinen K, Hämäläinen R, De Wever B. Lifelong learning: formal, non-formal and informal learning in the context of the use of problem-solving skills in technology rich environments. Br J Edu Technol. 2019;50(4):1759–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12807.

Okoli C. A guide to conducting a standalone systematic literature review. Commun Assoc Inf Syst. 2015;37(1):879–910. https://doi.org/10.17705/1cais.03743.

Olvares-Cuhat G. How to tailor TELL tools for older L2 learners. Estudios de Lingüística Inglesa Aplicada. 2018;18:81–104. https://doi.org/10.12795/elia.2018.i18.04.

Palo V. De, Limone P, Monacis L. Enhancing e-learning in old age Enhancing e-learning in old age. 2018.

Pappas MA, Demertzi E, Papagerasimou Y, Koukianakis L, Voukelatos N, Drigas A. Cognitive-based E-learning design for older adults. Soc Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8010006.

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2008). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. In Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887

Robinson P, Lowe J. Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2015;39(2):103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12393.

Seah ETW, Kaufman D, Sauvé L, Zhang F. Play, learn, connect: older adults’ experience with a multiplayer, educational, digital Bingo game. J Educ Comput Res. 2018;56(5):675–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633117722329.

Shang L, Zuo M. Investigating older adults’ intention to learn health knowledge on social media. Educ Gerontol. 2020;46(6):350–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2020.1759188.

Sheila RC, Elizabeth AY, Ronald WB, Vicki Winstead WAA. Designing technology training for older adults in continuing care retirement communities. New York: CRC Press; 2017.

Shi Y, Ma D, Zhang J, Chen B. In the digital age : a systematic literature review of the e-health literacy and influencing factors among Chinese older adults. 2021.

Smith D, Zheng R, Metz A, Morrow S, Pompa J, Hill J, Rupper R. Role of cognitive prompts in video caregiving training for older adults: optimizing deep and surface learning. Educ Gerontol. 2019;45(1):45–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2019.1580442.

Tsai HYS, Rikard RV, Cotten SR, Shillair R. Senior technology exploration, learning, and acceptance (STELA) model: from exploration to use–a longitudinal randomized controlled trial. Educ Gerontol. 2019;45(12):728–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2019.1690802.

Tsang M. Connecting and caring: innovations for healthy ageing. Bull World Health Org. 2012;90(3):162–3. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.12.020312.

Tyler M, De George-Walker L, Simic V. Motivation matters: Older adults and information communication technologies. Stud Educ Adults. 2020;52(2):175–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2020.1731058.

Vošner HB, Bobek S, Kokol P, Krečič MJ. Attitudes of active older Internet users towards online social networking. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:230–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.014.

Vroman KG, Arthanat S, Lysack C. “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;43:156–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.018.

Vulpe S, Crăciun A. Silver surfers from a European perspective: technology communication usage among European seniors. Eur J Ageing. 2020;17(1):125–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00520-2.

Wagner N, Hassanein K, Head M. Computer use by older adults: a multi-disciplinary review. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(5):870–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.029.

Xavier AJ, D’orsi E, De Oliveira CM, Orrell M, Demakakos P, Biddulph JP, Marmot MG. English longitudinal study of aging: can internet/e-mail use reduce cognitive decline? J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(9):1117–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glu105.

Xiao Y, Watson M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J Plan Educ Res. 2019;39(1):93–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X17723971.

Yasim IMM, Lubis MA, Noor ZAM, Kamarudin MY. The use of teaching aids in the teaching and learning of Arabic language vocabulary. Creat Educ. 2016;07(03):443–8. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.73044.

Acknowledgements

The team would like to thank the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education for funding this study under Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS Nos. FRGS/1/2020/SS10/UNISEL/03/4). This work was supported by Universiti Selangor (UNISEL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmad, N.A., Abd Rauf, M.F., Mohd Zaid, N.N. et al. Effectiveness of Instructional Strategies Designed for Older Adults in Learning Digital Technologies: A Systematic Literature Review. SN COMPUT. SCI. 3, 130 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01016-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-022-01016-0