Abstract

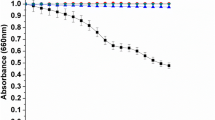

Chromoblastomycosis is a fungal chronic disease, which affects humans, especially in cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. There is no standard treatment for Chromoblastomycosis, and it is a therapeutic challenge, due natural resistance of their causative agents, inadequate response of patients and common cases of relapse. Protocols for determination of antifungal drugs susceptibility are not standardized for chromoblastomycosis agents and endpoint definition is usually based on visual inspection, which depends on the analyst, making it sometimes inaccurate. We presented a colorimetric and quantitative methodology based on resazurin reduction to resofurin to determine the metabolic status of viable cells of Fonsecaea sp. Performing antifungal susceptibility assay by a modified EUCAST protocol allied to resazurin, we validated the method to identify the minimum inhibitory concentrations of itraconazole, fluconazole, amphotericin B, and terbinafine for eight Fonsecaea clinical isolates. According to our data, resazurin is a good indicator of metabolic status of viable cells, including those exposed to antifungal drugs.

Lay abstract

This work aimed to test resazurin as an indicator of the metabolic activity of Fonsecaea species in susceptibility assays to antifungal drugs. Species of this genus are the main causative agents of Chromoblastomycosis, which affects humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

de Brito AC, de J. S. Bittencourt M (2018) Chromoblastomycosis: An etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An Bras Dermatol 93(4):495–506. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187321

De Queiroz-telles F et al. (2017) Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 30(1):233–276, [Online]. Available: http://cmr.asm.org/content/30/1/233.long

Santos DWCL et al (2020) Chromoblastomycosis in an endemic area of Brazil: a clinical-epidemiological analysis and a worldwide haplotype network. J Fungi 6(4):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6040204

Passero LFD, Cavallone IN, Belda W (2021) Reviewing the etiologic agents, microbe-host relationship, immune response, diagnosis, and treatment in chromoblastomycosis. J Immunol Res 2021:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9742832

World Health Organization (2017) Neglected Tropical Diseases. Program. Available online: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/en/. Accessed 10 Jan 2024

Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci DR, Caceres DH, Chiller T, Pasqualotto AC (2017) Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Infect Dis 17(11):e367–e377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30306-7

Andrade TS, Castro LGM, Nunes RS, Gimenes VMF, Cury AE (2004) Susceptibility of sequential Fonsecaea pedrosoi isolates from chromoblastomycosis patients to antifungal agents. Antimykotika-Empfindlichkeit von sequenziellen Fonsecaea pedrosoi-Isolaten von Chromoblastomykose-Patienten. Mycoses 47(5–6):216–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00984.x

Najafzadeh MJ, Badali H, Illnait-Zaragozi MT, De Hoog GS, Meis JF (2010) In vitro activities of eight antifungal drugs against 55 clinical isolates of Fonsecaea spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54(4):1636–1638. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01655-09

Daboit TC et al (2014) In vitro susceptibility of chromoblastomycosis agents to five antifungal drugs and to the combination of terbinafine and amphotericin B. Mycoses 57(2):116–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12111

Zheng H et al (2019) In vitro susceptibility of dematiaceous fungi to nine antifungal agents determined by two different methods. Mycoses 0–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12895

Najafzadeh MJ, Sun J, Vicente V, Xi L, Van Den Ende AHGG, De Hoog GS (2010) Fonsecaea nubica sp. nov, a new agent of human chromoblastomycosis revealed using molecular data. Med Mycol 48(6):800–806. https://doi.org/10.3109/13693780903503081

de Andrade TS et al (2019) Chromoblastomycosis in the Amazon region, Brazil, caused by Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Fonsecaea nubica, and Rhinocladiella similis: clinicopathology, susceptibility, and molecular identification. Med Mycol 58(2):172–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myz034

Arendrup MC, Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Guinea J, Cuenca-Estrella M, Lagrou K et al (2021) The Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Method for the Determination of Broth Dilution Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of Antifungal Agents for Conidia Forming Moulds. EUCAST E.Def. 9.3.2 2020, pp 1–23. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/astoffungi/methodsinantifungalsusceptibilitytesting/ast_of_moulds/. Accessed 1 Jan 2023

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2017) Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi: approved standard, 3rd ed CLSI document M38-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA

Monteiro MC et al (2012) A new approach to drug discovery: high-throughput screening of microbial natural extracts against Aspergillus fumigatus using resazurin. J Biomol Screen 17(4):542–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087057111433459

Präbst K, Engelhardt H, Ringgeler S, Hübner H (2017) Basic colorimetric proliferation assays: MTT, WST, and resazurin. In: Gilbert D, Friedrich O (eds) Cell Viability Assays. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 1601. Humana Press, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6960-9_1

Rampersad SN (2012) Multiple applications of alamar blue as an indicator of metabolic function and cellular health in cell viability bioassays. Sensors (Switzerland) 12(9):12347–12360. https://doi.org/10.3390/s120912347

Braissant O, Astasov-Frauenhoffer M, Waltimo T, Bonkat G (2020) A review of methods to determine viability, vitality, and metabolic rates in microbiology. Front Microbiol 11(2):1–25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.547458

Riss TL, Moravec RA, Niles AL, Duellman S, Benink HA, Worzella TJ, Minor L (2004) Cell Viability Assays. 2013 May 1 [updated 2016 Jul 1]. In: Markossian S, Grossman A, Brimacombe K, Arkin M, Auld D, Austin C, Baell J, Chung TDY, Coussens NP, Dahlin JL, Devanarayan V, Foley TL, Glicksman M, Gorshkov K, Haas JV, Hall MD, Hoare S, Inglese J, Iversen PW, Kales SC, Lal-Nag M, Li Z, McGee J, McManus O, Riss T, Saradjian P, Sittampalam GS, Tarselli M, Trask OJ Jr, Wang Y, Weidner JR, Wildey MJ, Wilson K, Xia M, Xu X (eds) Assay Guidance Manual [Internet]. Eli Lilly & Company and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Bethesda (MD)

Repp KK, Menor SA, Pettit RK (2007) Microplate Alamar blue assay for susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Med Mycol 45(7):603–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780701581458

Deng S et al. (2018) Combination of amphotericin B and terbinafine against melanized fungi associated with chromoblastomycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (March):AAC.00270–18. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00270-18

Temmerman R et al (2020) Agreement of quantitative and qualitative antimicrobial susceptibility testing methodologies: the case of enrofloxacin and avian pathogenic escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 11(September):1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.570975

Arendrup MC, Friberg N, Mares M, Kahlmeter G, Meletiadis J, Guinea J (2020) Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). How to interpret MICs of antifungal compounds according to the revised clinical breakpoints v. 10.0 European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing (EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect 26(11):1464–1472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.007

Kauffman CA, Zarins LT (1999) Colorimetric method for susceptibility testing of voriconazole and other triazoles against Candida species. Mycoses 42(9–10):539–542. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0507.1999.00511.x

De Paula E Silva ACA et al (2013) Microplate alamarblue assay for paracoccidioides susceptibility testing. J Clin Microbiol 51(4):1250–1252. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02914-12

Leong C, Buttafuoco A, Glatz M, Bosshard PP (2017) Antifungal susceptibility testing of Malassezia spp. with an optimized colorimetric broth microdilution method. J Clin Microbiol 55(6):1883–1893. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00338-17

Yamaguchi H, Uchida K, Nagino K, Matsunaga T (2002) Usefulness of a colorimetric method for testing antifungal drug susceptibilities of Aspergillus species to voriconazole. J Infect Chemother 8(4):374–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10156-002-0201-y

Jahn B, Stüben A, Bhakdi S (1996) Colorimetric susceptibility testing for Aspergillus fumigatus: comparison of menadione-augmented 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl- 2H-tetrazolium bromide and Alamar Blue tests. J Clin Microbiol 34(8):2039–2041. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.34.8.2039-2041.1996

Mania D, Hilpert K, Ruden S, Fischer R, Takeshita N (2010) Screening for antifungal peptides and their modes of action in Aspergillus nidulans. Appl Environ Microbiol 76(21):7102–7108. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01560-10

Invitrogen, “alamarBlue ® Assay,” Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/document-connect/document-connect.html?url=https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets%2FLSG%2Fmanuals%2FAlamarBluePIS.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2024

O’Brien J, Wilson I, Orton T, Pognan F (2000) Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem 267(17):5421–5426. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01606.x

Borra RC, Lotufo MA, Gagioti SM, de M. Barros F, Andrade PM (2009) A simple method to measure cell viability in proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Braz Oral Res 23(3):255–262. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-83242009000300006

Santos ALS et al (2007) Biology and pathogenesis of Fonsecaea pedrosoi, the major etiologic agent of chromoblastomycosis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31(5):570–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00077.x

Fai PB, Grant A (2009) A rapid resazurin bioassay for assessing the toxicity of fungicides. Chemosphere 74(9):1165–1170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.078

Siopi M, Pournaras S, Meletiadis J (2017) Comparative evaluation of sensititre YeastOne and CLSI M38–A2 reference method for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus spp. against Echinocandins. J Clin Microbiol 55(6):1714–1719. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00044-17

Tiballi RN, He X, Zarins LT, Revankar SG, Kauffman CA (1995) Use of colorimetric system for yeast susceptibility testing. J Clin Microbiol 33(4):915–917. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.33.4.915-917.1995

Far FE, Al-Obaidi MMJ, Desa MNM (2018) Efficacy of modified Leeming-Notman media in a resazurin microtiter assay in the evaluation of in-vitro activity of fluconazole against Malassezia furfur ATCC 14521. J Mycol Med 28(3):486–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.04.007

Liu M, Seidel V, Katerere DR, Gray AI (2007) Colorimetric broth microdilution method for the antifungal screening of plant extracts against yeasts. Methods 42(4):325–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.02.013

da S. Hellwig AH, Heidrich D, Zanette RA, Scroferneker ML (2019) In vitro susceptibility of chromoblastomycosis agents to antifungal drugs: a systematic review. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 16:108–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2018.09.010

Coelho RA et al (2018) Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of clinical strains of Fonsecaea spp. isolated from patients with chromoblastomycosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12(7):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006675

Andrade TS, Castro LGM, Nunes RS, Gimenes VMF, Cury AE (2004) Susceptibility of sequential Fonsecaea pedrosoi isolates from chromoblastomycosis patients to antifungal agents. Mycoses 47(5–6):216–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.00984.x

Acknowledgements

We thank Nucleus of Mycology from Adolfo Lutz Institute, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Fiocruz) and University of Paraná (Paraná Network of Biological Collections) for kindly providing Fonsecaea isolates used in this study.

Funding

The research was funded by Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal (FAP-DF) [DEMANDA ESPONTÂNEA 00193–00000180/2019–91 to LF and FAP-DF-DEMANDA ESPONTÂNEA 193.000.805/2015 to ALB]; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) [PhD Scholarship to TSH].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Rosana Puccia

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anamelia Lorenzetti Bocca, Larissa Fernandes the authors share the senior authorship.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Herman, T.S., da Silva Goersch, C., Bocca, A.L. et al. Resazurin to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration on antifungal susceptibility assays for Fonsecaea sp. using a modified EUCAST protocol. Braz J Microbiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-024-01293-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-024-01293-2