Abstract

Gratitude activities have been shown to increase well-being and other positive outcomes in numerous experiments to date. The current study tested whether self-directed gratitude interventions that vary by type (i.e., social vs. nonsocial) and format (i.e., long-form letters vs. shorter lists) produce differential benefits. To that end, 958 Australian adults were assigned to one of six activities to complete each day for 1 week, including five gratitude activities that varied by type and format and an active control condition (i.e., keeping track of daily activities). Regressed change analyses revealed that, overall, long-form writing exercises (i.e., essays and letters) resulted in greater subjective well-being and other positive outcomes than lists. Indeed, those who were instructed to write social and nonsocial gratitude lists did not differ from controls on any outcomes. However, participants who wrote unconstrained gratitude lists—that is, those who wrote about any topics they wanted—reported greater feelings of gratitude and positive affect than did controls. Finally, relative to the other gratitude conditions, participants who wrote gratitude letters to particular individuals in their lives not only showed stronger feelings of gratitude, elevation, and other positive emotions but also reported feeling more indebted. This study demonstrates that not only does gratitude “work” to boost well-being relative to an active neutral activity, but that some forms of gratitude may be more effective than others. We hope these findings help scholars and practitioners to develop, tailor, implement, and scale future gratitude-based interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As a psychological construct, gratitude involves acknowledging a benefit received from a benefactor or an external source (Emmons & McCullough, 2003). Gratitude can be conceptualized as both a fleeting emotional state (i.e., the momentary experience of thankfulness) and as a trait (i.e., the tendency to experience this state). The present research focused on the state, or short-term, experience of gratitude.

Scholars differ in their definitions of gratitude, with some proposing that gratitude is an inherently social process, involving recognition of a kindness or benefit conferred from another person (Emmons, 2004). Others have suggested that individuals experience different types of gratitude, depending on whether the feeling is triggered by a specific benefit versus general appreciation, or whether one is grateful to another person versus for the circumstances of one’s life (Ahrens & Forbes, 2014; Lambert et al., 2009; Steindl-Rast, 2004). A goal of the current study is to better understand the complexities of experienced gratitude, whether in response to a specific kindness extended by an individual or as a global feeling of appreciation for one’s life fortunes.

Gratitude as an Interpersonal Process

Although individuals can feel grateful for their life circumstances, life events, or their material possessions, gratitude has unique social implications—namely, to develop, maintain, and strengthen interpersonal relationships (Algoe, 2012). Indeed, numerous studies have revealed the relational benefits of gratitude, including greater relationship satisfaction and relationship maintenance behavior (Gordon et al., 2012; Kubacka et al., 2011). These relational benefits may, however, come at a cost, as gratitude is sometimes experienced as a mixed emotional state (Layous et al., 2017). For example, participants reported more indebtedness, guilt, and shame when they wrote a gratitude letter to someone important versus about something important in their lives (Oishi et al., 2019). The present study investigates the potential for gratitude to elicit both positive and negative feelings.

Gratitude Interventions

In addition to its interpersonal benefits, gratitude is associated with numerous positive outcomes. Correlational research demonstrates robust associations between gratitude and positive psychological outcomes, and experimental work shows that gratitude interventions boost both the affective and cognitive components of subjective well-being (Armenta et al., 2020; Davis et al., 2016; Rash et al., 2011; Sheldon & Yu, 2021) and reduce depression and anxiety (meta-analytic g = −0.23; Cregg & Cheavens, 2021). Gratitude interventions have been shown to impact beneficial psychological outcomes beyond subjective well-being, including feelings of connectedness with others, elevation, and self-improvement motivation (Armenta et al., 2020; Layous et al., 2017; Walsh, Regan, & Lyubomirsky, 2022).

Notably, experimental manipulations of gratitude draw on a variety of gratitude activities (e.g., prompting participants to express gratitude through letters, lists, or verbally), and more research is needed to understand how features of these activities impact their efficacy (Jans-Beken et al., 2019). Researchers have begun to investigate the nuanced differences between methods of gratitude expression, but more work is needed to understand how specific features of these activities impact well-being and other positive outcomes (Kaczmarek et al., 2015; Sheldon & Yu, 2021; Walsh, Regan, Twenge et al., 2022). Because gratitude activities may differ in format (e.g., writing a gratitude letter or a gratitude list) and content (e.g., expressing gratitude to a specific person or about the conditions of one’s life), they may differentially impact psychological functioning and well-being. Participants are likely to write fewer words when asked to list blessings, for example, than when asked to write a gratitude letter to a specific other. The open-ended format of a gratitude letter or essay may prompt participants to write more expressively, a process that has been associated with positive outcomes and the reduction of depressive symptoms in previous research (Booker & Dunsmore, 2017; Gortner et al., 2006; Toepfer & Walker, 2009). Conversely, expressing gratitude to a specific benefactor in letter form could also be relatively more difficult or uncomfortable for participants, potentially leading to feelings of indebtedness and other socially-relevant negative emotions. An aim of the present research is to understand whether the format of gratitude interventions leads to different psychological outcomes.

Present Study

The present study contrasted gratitude activities varying by format (letters vs. lists) and target (social or gratitude “to” vs. nonsocial or gratitude “for”). Varying features of gratitude activities allowed for direct comparisons to identify the elements that are most relevant to well-being outcomes. To that end, we randomly assigned participants to engage in one of four gratitude writing activities varying by format and target: (1) social gratitude letters, (2) nonsocial gratitude letters, (3) social gratitude lists, and (4) nonsocial gratitude lists. Participants who wrote gratitude letters did so privately—that is, they completed the exercise as part of an online survey assessment and were not instructed to deliver them. Instructing participants to deliver their gratitude letters (or lists) would have not only created a confound (i.e., sharing the letters in addition to writing them), but may also have caused the intervention to backfire for some participants (Fritz & Lyubomirsky, 2018; Ruini & Mortara, 2022).

In addition to testing theory-driven research questions, the present study also had a practical aim—namely, to contrast multiple gratitude intervention(s) to inform evidence-based recommendations, as gratitude interventions are already used in a variety of applied contexts, including schools (Renshaw & Olinger Steeves, 2016) and therapeutic settings (Emmons & Stern, 2013). In service of this practical aim, we included a comparison condition similar to the “counting blessings” (or “gratitude journal”) intervention that is commonly used in research and practice. Participants in this condition were not constrained to write about either people or things for which they are grateful, but rather were able to freely list whatever came to mind as a source of gratitude.

Finally, despite accumulating evidence for the benefits of gratitude, questions remain about the effect sizes and practical implications of gratitude interventions (Davis et al., 2016). As is the case with other self-administered well-being interventions, gratitude activities tend to yield small effects (Dickens, 2017). Given the relatively “low-touch” nature of these interventions, small effect sizes are to be expected, and may accumulate over time (Funder & Ozer, 2019). Although the main focus of the present research was to understand the implications of varying the target and format of gratitude interventions, we also included an active control condition to establish the overall efficacy of gratitude interventions relative to a neutral activity. Comparing gratitude activities to a neutral activity allowed us to rule out whether their effects are due to a placebo effect of simply engaging in a new activity and tracking one’s feelings over time.

In sum, the current study was designed to address four research questions:

-

1.

Do gratitude activities “work”? We hypothesized that each of the gratitude conditions would lead to greater well-being benefits than an active control condition.

-

2.

Do social gratitude activities outperform nonsocial ones? We hypothesized that social gratitude conditions would lead to greater well-being benefits than nonsocial gratitude conditions.

-

3.

Does gratitude expressed via longer writing formats (letters or essays) have stronger effects than gratitude expressed via shorter lists? We hypothesized that gratitude letters/essays would yield greater well-being benefits than gratitude lists.

-

4.

Do social gratitude letters outperform other gratitude exercises? Given our predictions about the most efficacious target (social over nonsocial) and format (letter over list), we hypothesized that those assigned to express gratitude to specific people would experience the strongest well-being outcomes of all conditions.

Method

Participants

Australian adults (N = 958; 52.2% female) were recruited from Pureprofile, an online panel company. All participants, including those in the active control condition, were told that they may be asked to participate in “positive activities” but were not told that the activities would improve their well-being.Footnote 1 Most (87%) were White, 10.5% were Black, and the remainder were other ethnicities (4.8%). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 89 (M = 47.8, SD = 16.9), with the majority (65.6%) having at least one child (M = 2.34, SD = 1.18; range = 0 to 8 children).

Procedure

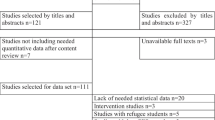

Participants were randomly assigned to one of six conditions, including four conditions that varied by type of gratitude (social/“gratitude to” vs. nonsocial/“gratitude for”) and format (list format vs. letters or essays): social gratitude letters, nonsocial gratitude letters, social gratitude lists, nonsocial gratitude lists. The other two comparison conditions comprised unconstrained gratitude lists and active control (see Fig. 1 for an overview of the study design).

Participants in the social gratitude letter condition (n = 167) were instructed to write gratitude letters to benefactors, while those in the nonsocial gratitude letter (n = 154) condition were instructed to write essays about things for which they are grateful, excluding people. Similarly, those assigned to the social gratitude list condition (n = 160) were instructed to write lists of people to whom they are grateful, while those in the nonsocial gratitude list (n = 170) condition were instructed to write lists of things for which they are grateful, excluding people. Participants assigned to the unconstrained list condition (n = 158) were prompted to write lists of people or things for which they are grateful. Finally, participants assigned to the active control condition (n = 149) were instructed to write about their daily activities. This study was approved by our university’s institutional review board.

The study took place over the course of 15 days, and all surveys were delivered via online Qualtrics surveys. After completing a pre-test survey (T1), participants were instructed to complete their assigned writing exercise each day for 1 week (T2–T7). Participants completed their daily writing exercise at the end of each daily survey, in an open-ended text box. Because a goal of the present study was to compare gratitude activities that varied by format (i.e., letters vs. lists), we chose to administer the activities multiple times across a relatively short time period to avoid burdening participants. That is, although the gratitude list activities may have been more effective if administered daily for multiple weeks, the longer letter/essay-writing activities may have become burdensome or repetitive. Participants completed a post-test survey at the end of the first week (T8), and a follow-up survey 1 week later (T9).

Measures

Measures included in the present analyses are listed below. Participants completed a longer battery of measures in this study, but space precludes us from including all measures in this report.

Gratitude

Participants completed the Gratitude Questionnaire—Six Item Form (GQ-6; McCullough et al., 2002) and the emotion subscale of the Multi-Component Gratitude Measure (MCGM; Morgan et al., 2017) during pre-test (T1), post-test (T8), and follow-up (T9) assessments. The GQ-6 includes items such as “Lately I notice that I have much in life to be thankful for.” Like the GQ-6, the 6-item emotion subscale of the MCGM measures feelings of gratitude, but also includes specific items that capture both social (“There are so many people that I feel grateful for”) and nonsocial (“There are many things that I am grateful for”) gratitude. Items from both the GQ-6 and MCGM were rated on 7-point Likert scales, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Both measures of gratitude demonstrated good reliability, with ωs ranging across all timepoints from .86 to .88 for the GQ-6 and from .93 to .94 for the MCGM. The GQ-6 and MCGM were originally included with the intent of creating a composite gratitude measure with subscales representing social and nonsocial gratitude. An exploratory factor analysis, however, did not support this approach. Given the results of this factor analysis and a correlation of .82 (p < .001) between these measures at pre-test, the GQ-6 and MCGM were combined into a single composite measure of state gratitude.

Life Satisfaction

Participants completed the 5-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) at T1, T8, and T9, and a single item (“I am satisfied with my life”) at T2–T7 (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The reliability of the SWLS ranged from ω = .92 to .93 across all timepoints.

Affect

A modified 19-item version of the Affect Adjective Scale (AAS; Diener & Emmons, 1984) was administered at all nine timepoints. The AAS measures the extent to which participants felt positive (e.g., pleased) and negative (e.g., frustrated) affect, and, notably, includes both high-arousal (e.g., joy) and low-arousal (e.g., peaceful/serene) emotions. All items were rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The reliability of the composites ranged from ω = .94 to .96 for positive affect and from ω = .89 to .91 for negative affect across all timepoints.

Based on previous research on the proximal experience of gratitude interventions, we also added socially relevant negative emotions to the standard AAS, including indebted, embarrassed, uncomfortable, guilty, and ashamed (Layous et al., 2017). The present analysis focuses on the single-item measure of indebtedness in light of prior research showing that gratitude interventions specifically evoke feelings of indebtedness (Layous et al., 2017; Oishi et al., 2019).

Psychological Needs

Participants completed a modified version of the Balanced Measure of Psychological needs (BMPN; Sheldon & Hilpert, 2012) at all nine timepoints. Each psychological need was assessed by three items rated on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Sample items include “I feel very capable in what I do” (competence), “I feel free to do things my own way” (autonomy), and “I feel close and connected with other people who are important to me” (connectedness). Reliability ranged from: ω = .83 to .95 for the competence items; ω = .86 to .94 for the autonomy items; and ω = .91 to .96 for the connectedness items.

Elevation

At all nine timepoints, participants completed a 6-item measure of elevation (Schnall et al., 2010), rating the extent to which they experienced feelings of elevation (e.g., “a warm feeling in your chest” and “uplifted”; 1 = do not feel at all; 7 = feel very strongly) over the past seven days (T1, T8, T9) or “right now” (T2–T7). The reliability for elevation ranged from ω = .89 to .94 across all timepoints.

Analytic Approach

Although participants completed measures at all nine timepoints, the present analysis focused on testing condition differences only at post-test and follow-up. To test the hypothesized differences in outcomes by condition, we used regressed (i.e., residualized) change models to predict post-test and follow-up scores from condition, while holding pre-test scores constant. This analytic approach allowed for the comparison between conditions at post-test and follow-up while statistically accounting for participants’ pre-test levels of each outcome measure. Further, this approach was better suited for data with unequal sample sizes per condition than other methods (e.g., repeated-measures ANOVA). All regression coefficients were converted to partial correlations for ease of interpretation and comparability between models. We applied the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate given the large number of comparisons in our analyses (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

To determine whether attrition in our sample was random or systematic, we conducted logistic regression analyses predicting missingness at post-test and follow-up from condition. These analyses indicated that missingness differed slightly by condition, such that those in the social letter and social list writing conditions were more likely than those in the control condition to have missing data at post-test and follow-up, and those in the nonsocial essay condition were more likely than those in the control group to have missing data at follow-up (see Table 1 for means, standard deviations, and sample sizes by condition at each timepoint). To account for missing data and unequal sample sizes due to attrition, all models were estimated using a structural equation modeling approach to employ full information maximum likelihood (FIML) in the estimation of model parameters. FIML has been shown to produce less biased parameter estimates than other methods of handling missing data, such as multiple imputation and pairwise and listwise deletion (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). All models were estimated using the lavaan R package (Rosseel, 2012).

Finally, to contextualize our results, we conducted additional analyses to determine whether conditions differed in terms of the average number of words written by participants across timepoints. A one-way ANOVA revealed that conditions significantly differed in terms of their average word count across the intervention period, F(5, 592) = 22.94, p < .001; average word count was log-transformed. A post hoc Tukey test showed that the control, nonsocial letter, and social letter conditions each differed significantly from the unconstrained, nonsocial, and social list conditions (all p values < .001) but did not differ from each other in terms of average words written across all timepoints (all p values >.05).

Results

Are Gratitude Exercises Effective Relative to an Active Control Activity?

First, we ran a series of regressed change models with condition dummy-coded such that the control condition served as the reference group against all gratitude conditions combined (see Table 2 for partial r coefficients). Overall, participants who completed gratitude activities reported greater feelings of gratitude, indebtedness, connectedness, and elevation compared to the active control group at post-test (see Table S1 in the Supplementary information). These differences were not sustained at follow-up, with the exception of gratitude. The post-test differences in feelings of connectedness and follow-up differences in feelings of gratitude between the active control group and gratitude conditions became marginally significant after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. The post-test difference in feelings of elevation was no longer statistically significant after this procedure.

Second, to better understand the effect of specific gratitude activities, we unpacked these results by running a series of regressed change models with condition dummy-coded such that the control condition served as the reference group against each of the other conditions. Participants in the social letter, nonsocial letter, and unconstrained list conditions significantly differed from those in the control condition at post-test (see Tables S2, S3, S4, S5, S6 in the Supplementary information). Specifically, those who wrote social gratitude letters reported feeling greater indebtedness, elevation, gratitude, positive affect, and connectedness than those in the control condition at post-test. Those who wrote nonsocial gratitude essays reported feeling higher levels of gratitude, autonomy, connectedness, and indebtedness at post-test than controls. The differences in feelings of autonomy and connectedness between the nonsocial gratitude essay and active control conditions became marginally significant after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, and the difference in feelings of indebtedness was no longer statistically significant. Participants in the unconstrained list condition reported feeling more gratitude and positive affect than controls. Participants who completed gratitude activities did not differ significantly from those in the control condition in their reported feelings of competence, negative affect, and life satisfaction.

Most condition differences mentioned above did not hold from pre-test to follow-up. The exceptions were that, compared to controls, individuals who wrote social gratitude letters reported feeling more grateful and indebted at follow-up. Individuals who wrote unconstrained gratitude lists also reported higher levels of gratitude than those who tracked their daily activities at follow-up, although this difference was no longer significant after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Notably, those in the social and nonsocial list writing conditions did not significantly differ in any outcomes compared to those in the control condition at both post-test and follow-up.

Are Social Gratitude Exercises More Effective Than Nonsocial Ones?

We then conducted regressed change analyses to determine whether those in the social conditions differed from those in the nonsocial conditions (excluding the unconstrained list and control conditions). Contrary to our second hypothesis, with one exception, the two social conditions did not significantly differ from the two nonsocial conditions from pre-test to post-test or follow-up (see Table S7 in Supplementary information). However, participants in the social gratitude conditions (letters and lists) reported greater feelings of indebtedness at post-test relative to those who engaged in nonsocial gratitude activities.

Are Gratitude Letters and Essays More Effective Than Gratitude Lists?

Third, we compared the two long-form writing activities to the two gratitude list conditions to determine whether the format of gratitude interventions predicts changes in well-being and other psychological outcomes at post-test. Condition was dummy coded such that the social and nonsocial list writing activities served as a reference group for all comparisons (see Table S8 in the Supplementary information). Compared to those in the two list writing conditions, participants who wrote either social or nonsocial gratitude letters/essays reported feeling more elevation, gratitude, indebtedness, positive affect, and life satisfaction at post-test. Those in the long form writing conditions also reported feeling higher levels of elevation and positive affect at the follow-up assessment 1 week later. No statistically significant differences emerged between these conditions in psychological need satisfaction (autonomy, competence, and connectedness) or negative affect.

Are Social Gratitude Letters More Effective Than Other Gratitude Exercises?

In light of our fourth hypothesis—namely, that the social gratitude letter would be the most effective activity—we conducted a series of regressed change models with condition dummy-coded, such that the social letter condition served as the reference group against each of the other conditions.Footnote 2 These pairwise comparisons support the general pattern of results described previously (see Tables S9, S10, S11, S12 in the Supplementary information). Those in the social letter writing condition reported greater feelings of elevation, positive affect, gratitude, and life satisfaction relative to those in the social list condition. Participants who wrote social gratitude letters also reported experiencing more elevation, gratitude, positive affect relative to those in the nonsocial list condition. Compared to those in the nonsocial gratitude essay and unconstrained list conditions, participants who wrote social gratitude letters reported higher levels of elevation. Despite the apparent well-being benefits of writing social gratitude letters, this activity also led participants to report stronger feelings of indebtedness than each of the other gratitude conditions at post-test.

Although many of these effects were not maintained in the week following the intervention period, the results of our follow-up analyses indicated that writing social gratitude letters may have well-being benefits that are more robust relative to writing a social gratitude list. Those in the social letter writing condition reported feeling more elevation, positive affect, gratitude, connectedness, and life satisfaction at follow-up than those in the social list writing condition. The follow-up difference in feelings of gratitude between participants who wrote social gratitude letters relative to those who wrote social lists became marginally significant after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure, and the follow-up differences in feelings of connectedness and life satisfaction were no longer significant. Participants’ feelings of indebtedness endured from post-test to follow-up relative to those who wrote unconstrained gratitude lists. Results of additional regressed change analyses comparing the social letter to other gratitude conditions (combined) are included in the Supplementary information (Table S13).

Discussion

Corroborating earlier work, this study provides evidence for the efficacy of gratitude interventions relative to a neutral exercise, while also revealing nuanced differences between specific gratitude activities. As expected, participants who wrote gratitude letters or essays reported greater benefits at post-test than those who kept track of their daily activities. Surprisingly, participants who wrote social and nonsocial gratitude lists not only failed to differ from one another, but they performed no better than those who listed their daily activities. The long form gratitude writing activities, however, largely outperformed list writing activities in terms of well-being outcomes at post-test (i.e., greater positive affect and life satisfaction) and, to a lesser extent, at follow-up. Finally, writing social gratitude letters led to greater benefits at post-test compared to writing social or nonsocial lists. Those who wrote social gratitude letters also reported greater feelings of elevation and indebtedness at post-test than those who wrote nonsocial essays and unconstrained lists (but failed to differ in other outcomes). This pattern of results suggests that feelings of elevation and indebtedness may be unique to socially relevant expressions of gratitude (i.e., gratitude to a specific benefactor). Further, our results suggest that this increase in feelings of elevation was not due to a halo effect of greater feelings of gratitude overall, as the social letter condition was the only group that significantly differed from the active control condition for this outcome.

Notably, very few of the significant differences between conditions were sustained at follow-up, and these differences were further attenuated after correcting for multiple comparisons. These small and short-lived effects at follow-up may suggest that gratitude exercises should be completed consistently to reap their benefits over time. Although few differences between conditions reached statistical significance, our results tentatively suggest that longer-form gratitude activities (i.e., gratitude letters and essays) have slightly more durable effects than list-writing activities. Given these marginal results, future research could investigate whether administering a gratitude letter-writing intervention across several weeks would be more beneficial than administering a list-writing intervention. Intervention dosage—a moderator we did not manipulate in the present research—may be especially relevant when comparing these activities over a longer time period, as participants may feel more burdened or fatigued by repeating a letter-writing activity multiple times per week for several weeks. That is, rather than manipulate the target and format of gratitude activities, future investigators could examine the optimal dosage and format of these activities to maximize the durability of their effects (cf. Lyubomirsky & Layous, 2013).

The present research has several limitations. First, participants only engaged in gratitude activities over a single week. Future research could examine the effects of practicing different types of gratitude activities for longer periods. Next, a stronger measure of indebtedness is needed in future work when comparing social and nonsocial gratitude, as the present study relied on a single-item measure. Future research could also measure other socially relevant positive emotions to further disentangle the unique subjective experience of expressing different “types” of gratitude (i.e., social vs. nonsocial). We also acknowledge that although our sample was more representative with regard to age and gender than the primarily college student samples used in previous gratitude interventions, our participants were mostly white, Australian adults (i.e., sampled from a Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic, or “WEIRD” population; Henrich et al., 2010), which significantly limits the generalizability of our findings. Thus, these effects should be replicated cross-culturally, and in a more ethnically diverse sample. Finally, an examination of moderators and mechanisms underlying the relationship between gratitude activities and psychological outcomes was beyond the scope of the current paper.

In sum, the results of this study hold implications not only for well-being and gratitude scholars, but for laypeople and practitioners. First, we found that writing a gratitude letter appears to be a more psychologically rich experience than simply writing a list of people or things for which one is grateful. Furthermore, this work adds to the body of evidence that gratitude—especially when expressed in narrative form—can be leveraged to enhance subjective well-being and other positive psychological outcomes. At the same time, following previous research, our study highlights that gratitude can be a mixed emotional experience. As such, we suggest that gratitude interventions be implemented with wisdom and care—that is, recognizing that reflecting on benefits received from others may lead a person to feel both uplifted and indebted by the same gift.

Notes

The study consent form included the following language: “The goal of this study is to examine positive activities. Some of the questions will concern your personality, daily habits, thoughts, and emotions.”

Because the social letter condition was dummy coded to serve as the reference group for these comparisons, effect sizes for outcomes where the social letter outperformed the other conditions are negative. These effect sizes have been multiplied by −1 to convey results in terms of the social letter’s efficacy in relation to other conditions.

References

Ahrens, A. H., & Forbes, C. N. (2014). Gratitude. In M. M. Tugade, M. L. Shiota, & L. D. Kirby (Eds.), Handbook of positive emotions (pp. 342–361). Guilford Press.

Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x

Armenta, C. N., Fritz, M. M., Walsh, L. C., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2020). Satisfied yet striving: Gratitude fosters life satisfaction and improvement motivation in youth. Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000896

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300.

Booker, J. A., & Dunsmore, J. C. (2017). Expressive writing and well-being during the transition to college: Comparison of emotion-disclosing and gratitude-focused writing. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 36(7), 580–606.

Cregg, D. R., & Cheavens, J. S. (2021). Gratitude interventions: Effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(1), 413–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00236-6

Davis, D. E., Choe, E., Meyers, J., Wade, N., Varjas, K., Gifford, A., Quinn, A., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Griffin, B. J., & Worthington, E. L. (2016). Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000107

Dickens, L. R. (2017). Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(4), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1323638

Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(5), 1105–1117. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.47.5.1105

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Emmons, R. A. (2004). The psychology of gratitude: An introduction. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

Emmons, R. A., & Stern, R. (2013). Gratitude as a psychotherapeutic intervention: Gratitude. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(8), 846–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22020

Enders, C., & Bandalos, D. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 8(3), 430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

Fritz, M. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2018). Whither happiness? When, how, and why might positive activities undermine well-being. The Social Psychology of Living Well, 101–115.

Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168.

Gordon, A. M., Impett, E. A., Kogan, A., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2012). To have and to hold: Gratitude promotes relationship maintenance in intimate bonds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028723

Gortner, E.-M., Rude, S. S., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2006). Benefits of expressive writing in lowering rumination and depressive symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 37(3), 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.01.004

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61–83.

Jans-Beken, L., Jacobs, N., Janssens, M., Peeters, S., Reijnders, J., Lechner, L., & Lataster, J. (2019). Gratitude and health: An updated review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1651888

Kaczmarek, L. D., Kashdan, T. B., Drążkowski, D., Enko, J., Kosakowski, M., Szäefer, A., & Bujacz, A. (2015). Why do people prefer gratitude journaling over gratitude letters? The influence of individual differences in motivation and personality on web-based interventions. Personality and Individual Differences, 75, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.004

Kubacka, K. E., Finkenauer, C., Rusbult, C. E., & Keijsers, L. (2011). Maintaining close relationships: Gratitude as a motivator and a detector of maintenance behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(10), 1362–1375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211412196

Lambert, N. M., Graham, S. M., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). A prototype analysis of gratitude: Varieties of gratitude experiences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(9), 1193–1207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209338071

Layous, K., Sweeny, K., Armenta, C., Na, S., Choi, I., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). The proximal experience of gratitude. PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0179123. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179123

Lyubomirsky, S., & Layous, K. (2013). How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412469809

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J.-A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

Morgan, B., Gulliford, L., & Kristjánsson, K. (2017). A new approach to measuring moral virtues: The Multi-Component Gratitude Measure. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.044

Oishi, S., Koo, M., Lim, N., & Suh, E. M. (2019). When gratitude evokes indebtedness. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 11(2), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12155

Rash, J. A., Matsuba, M. K., & Prkachin, K. M. (2011). Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 3(3), 350–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01058.x

Renshaw, T. L., & Olinger Steeves, R. M. (2016). What good is gratitude in youth and schools? A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates and intervention outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 53(3), 286–305.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An r package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Ruini, C., & Mortara, C. C. (2022). Writing technique across psychotherapies—from traditional expressive writing to new positive psychology interventions: A narrative review. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 52(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-021-09520-9

Schnall, S., Roper, J., & Fessler, D. M. T. (2010). Elevation leads to altruistic behavior. Psychological Science, 21(3), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609359882

Sheldon, K. M., & Hilpert, J. C. (2012). The balanced measure of psychological needs (BMPN) scale: An alternative domain general measure of need satisfaction. Motivation and Emotion, 36(4), 439–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9279-4

Sheldon, K. M., & Yu, S. (2021). Methods of gratitude expression and their effects upon well-being: Texting may be just as rewarding as and less risky than face-to-face. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1913639

Steindl-Rast, D. (2004). Gratitude as thankfulness and as gratefulness. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 282–288). Oxford University Press.

Toepfer, S., & Walker, K. (2009). Letters of gratitude: Improving well-being through expressive writing. Journal of Writing Research, 1(3), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2009.01.03.1

Walsh, L. C., Regan, A., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2022). The role of actors, targets, and witnesses: Examining gratitude exchanges in a social context. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1991449

Walsh, L. C., Regan, A., Twenge, J. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2022). What is the optimal way to give thanks? Comparing the effects of gratitude expressed privately, one-to-one via text, or publicly on social media. Affective Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00150-5

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was funded by the John Templeton Foundation (Grant 61113).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data Availability

Data, materials, and R code will be available on the Open Science Foundation at https://osf.io/rp34a/?view_only=9857064e8d2544c69889f9908ce14c12.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Riverside.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was collected from all participants.

Additional information

Handling editor: Laura Kubzansky

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 82 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Regan, A., Walsh, L.C. & Lyubomirsky, S. Are Some Ways of Expressing Gratitude More Beneficial Than Others? Results From a Randomized Controlled Experiment. Affec Sci 4, 72–81 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00160-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00160-3