Abstract

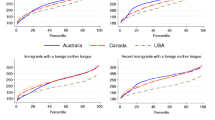

This paper presents the results of literacy proficiency projections using a microsimulation model that simultaneously projects future demographic, ethnocultural, and socioeconomic characteristics of the Canadian population. Factors linked with literacy skills of the working-age population are analyzed for both native- and foreign-born Canadians. The projection results show that literacy skills are likely to slightly decline between 2011 and 2061, as the positive effects of increasing education are canceled out by the important skill gap between native- and foreign-born Canadians. Results of the simulation suggest that plausible changes to immigrant selection policies could prevent against the associated literacy skill decline among the Canadian working-age population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Statistics Canada developed the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) through which the Survey of Adults Skills is conducted. In this survey, literacy proficiency is measured along a continuous scale ranging from 0 to 500, where a higher score indicates greater proficiency. The literacy-proficiency projections presented in this paper are based on PIAAC Survey data. Thus, the definition of literacy skills corresponds to the definition and conceptual framework undergirding this survey. For more information, see OECD (2017) and Statistics Canada (2017b).

Language skills refer to mother tongue and language most often spoken at home.

Canada Pension Plan (CPP). Retirement age in Canada is 65 years old for both men and women.

Are also excluded from the PIAAC survey sample—thus from the analyses—the population residing in institutions, on Aboriginal reserves, and on military bases.

A simple logarithmic transformation is made on the dependent variable (literacy score) to obtain regression coefficients that can be interpreted as showing the percentage effect of a unit change on the average score. The logarithmic transformation also ensures that the linear regression model will not lead to illogical predicted scores (below 0) during the simulation.

We use the standard threshold used by Statistics Canada to distinguish rural and urban areas. An urban area corresponds to an area with a population of at least 1000 and a density of 400 or more people per square kilometer.

The mother’s education level is also a measure of social and cultural capital which directly and indirectly impacts on the children skill development and socioeconomic status. See Augustine and Negraia (2018).

Intensity of reading books at home and of writing letters, memos, or emails at work were used. Life-wide learning is defined as occurring “in different context such as in the home, school, work, community, and other.” (Desjardins 2003b: 211)

The country of birth and country of highest diploma have similar categories. The richest countries of the world are grouped together and correspond to Western European countries, North American countries as well as Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, and South Korea.

This microsimulation model is built along a framework developed for the study of super-diversity in many countries including Canada, the USA, and 28 countries of the European Union (Bélanger et al. 2018a).

Super-diversity is a concept coined by Vertovec (2007) and refers to this emerging demographic regime of increasing ethnocultural diversity.

See Bélanger et al. (2018b) for more technical documentation of the microsimulation.

LSD-C’s point of departure is 2011 and its starting population is based on the 2011 National Household Survey public-use microdata file (NHS-PUMF) corrected for net undercoverage by age, sex, and province of residence.

Characteristics such as age, province of residence, education level, labor force participation status, and length of stay in Canada

Canada’s official immigration plans for 2017–2018 targets 300,000 new permanent residents per year, which represents a historic high compared to prior years (Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Departmental Plan 2017–2018 retrieved at http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/publications/dp/2017-2018/dp.asp on March 9, 2017). In view of the total Canadian population estimates of January 1, 2017 at 36.5 million, this target corresponds to an immigration rate of 0.82%, which is higher than the baseline scenario (BASE) rate. Among the G7 countries, Canada has the highest immigration rate; in fact, most of these countries have an immigration rate below 0.50%.

In LSD-C, education coefficients not only vary by generation status but also by sex, region of residence, visible minority status, mother tongue, and cohorts (Bélanger et al. 2018b).

References

Augustine, J. M., & Negraia, D. V. (2018). Can increased educational attainment among lower-educated mothers reduce inequalities in children’s skill development? Demography, 55(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0637-4.

Barone, C., & van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2011). Education, cognitive skills and earnings in comparative perspective. International Sociology, 26(4), 483–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580910393045.

Beaujot, R., & Kerr, D. (2015). Population change in Canada. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Bélanger, A., Sabourin, P., Marois, G., Van Hook, J., & Vézina, S. (2018a). A framework for the prospective analysis of super-diversity. (WP-18-008). Laxenburg: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

Bélanger, A., P. Sabourin, S. Vézina, G. Marois, K. D’Ovidio, D. Pelletier, and O. Lafontaine. (2018b). The Canadian microsimulation model (LSD-C): content, modules, and some preliminary results. In. Montréal: Institut national de la recherche scientifique. Working Paper no 2018–01. http://espace.inrs.ca/6830/. Accessed 20 Apr 2018.

Bonikowska, A., D. A. Green, and W. C. Riddell. (2010). Immigrant skills and immigrant outcomes under a selection system: the canadian experience. Paper presented at the conference on the economics of immigration 2010. Ottawa.

Carey, D. (2014). Overcoming skills shortages in Canada. OECD Economics Department Working Papers (No. 1143). Paris: OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jz123fgkxjl-en.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. 2017. Six selection factors – federal skilled workers (express entry). accessed 20 April 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/express-entry/become-candidate/eligibility/federal-skilled-workers/six-selection-factors-federal-skilled-workers.html.

Coleman, D. (2006). Immigration and ethnic change in low-fertility countries: a third demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 401–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00131.x.

Coulombe, S., Tremblay, J.-F., & Marchand, S. (2004). Literacy scores, human capital and growth across fourteen OECD countries. Ottawa: Statistique Canada.

Desjardins, R. (2003a). Determinants of economic and social outcomes from a life-wide learning perspective in Canada. Education Economics, 11(1), 11–38.

Desjardins, R. (2003b). Determinants of literacy proficiency: a lifelong-lifewide learning perspective. International Journal of Educational Research, 39, 205–245.

Green, A. G., & Green, D. (2004). The goals of Canada’s immigration policy: a historical perspective. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 13(1), 102–139.

Green, D., & Riddell, W. C. (2007). Literacy and the labour market: the generation of literacy and its impact on earnings for native born Canadians. (catalogue no. 89-552-MIE — No.18). Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Green, D., & Worswick, C. (2017). Canadian economics research on immigration through the lens of theories of justice. Canadian Journal of Economics, 50(5), 1262–1303.

Hanushek, E. A., Schwerdt, G., Wiederhold, S., & Wößmann, L. (2015). Returns to skills around the world: evidence from PIAAC. European Economic Review, 73, 103–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.10.006.

Hanushek, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2008). The role of cognitive skills in economic development. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(3), 607–668. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.46.3.607.

Hanushek, E. A., & Wößmann, L. (2007). The role of education quality in economic growth. In World Bank policy research working paper (WPS4122). Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Keslair, F. (2017). How much will the literacy level of the working-age population change from now to 2022? Paris: OECD Publishing.

Levy, F. (2010). How technology changes demands for human skills. OECD education working papers (No. 45). Paris: OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kmhds6czqzq-en.

Lutz, W. (2013). Demographic metabolism: a predictive theory of socioeconomic change. Population and Development Review, 38(s1), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00564.x.

McIntosh, S., & Vignoles, A. (2001). Measuring and assessing the impact of basic skills on labour market outcomes. Oxford Economic Papers, 53(3), 453–481.

OECD. (2016). Skills matter: further results from the survey of adult skills. In OECD skills studies. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258051-en.

OECD. (2017). Survey of adult skills (PIAAC). http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/. Accessed 20 Apr 2018.

Papademetriou, D. G., & Sumption, M. (2011). Rethinking points systems and employer-selected immigration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

Reder, S. (1994). Practice engagement theory: a sociocultural approach to literacy across languages and cultures. In B. M. Ferdman, R.-M. Weber, & A. G. Ramirez (Eds.), Literacy across languages and cultures (pp. 33–74). Albany NY: State University of New York Press.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Skills in Canada: first results from the programme for the international assessment of adult competencies (PIAAC). (Catalogue no. 89–555-X). Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2015). Population projections for Canada (2013 to 2063), provinces and territories (2013 to 2038). (Catalogue no. 91-520-X). Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2017a). Population growth: migratory increase overtakes natural increase. accessed 20 April 2018. https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2014001-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada (2017b). Program for the international assessment of adult competencies (PIAAC). http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl? Function=getSurvey&Id=132269. Accessed 20 Apr 2018.

Sweetman, A. (2004). Immigrant source country educational quality and canadian labour market outcomes. Analytical studies branch research paper series (catalogue no. 11F0019MIE — No. 234). Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465.

Xenogiani, T. (2017). Why are immigrants less proficient in literacy than native-born adults? Paris: OECD Publishing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vézina, S., Bélanger, A., Sabourin, P. et al. Literacy Skills of the Future Canadian Working-Age Population: Assessing the Skill Gap Between the Foreign- and Canadian-Born. Can. Stud. Popul. 46, 5–25 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-019-00002-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-019-00002-x