Abstract

We investigate a new filtering method to estimate the hidden states of random variables for multiple non-stationary time series data. This helps in analyzing small sample non-stationary macro-economic time series in particular and it is based on the frequency domain application of the separating information maximum likelihood (SIML) method, developed by Kunitomo et al. (Separating Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation for High Frequency Financial Data. Springer, New York, 2018), and Kunitomo et al. (Japan J Statistics Data Sci 2:73–101, 2020), and Nishimura et al. (Asic-Pacific Financial Markets, 2019). We solve the filtering problem of hidden random variables of trend-cycle, seasonal and measurement-errors components, and propose a method to handle macro-economic time series. We develop the asymptotic theory based on the frequency domain analysis for non-stationary time series. We illustrate applications, including some properties of the method of Müller and Watson (Econometrica 86-3:775–804, 2018), and analyses of some macro-economic data in Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There exists vast research on the use of statistical time series analysis for macro-economic time series. One important feature of macroeconomic time series, which is different from standard statistical time series analysis is that the observed time series is an apparent mixture of non-stationary and stationary components. The second feature is that the measurement errors in economic time series play important roles because macro-economic data are usually constructed from various sources, including sample surveys in major official statistics, while the statistical time series analysis often ignored measurement errors. Third, the sample size of macro-economic data is rather small, and we have about 120 time series observations for each series for quarterly data over 30 years. The quarterly GDP series, which is the most important data in the Japanese macro-economy, for instance, is regularly estimated and released by the cabinet office of Japan.Footnote 1 Fourth, to publish the seasonally adjusted data, the official agencies usually apply the X-12-ARIMA program, which uses the univariate reg-ARIMA model to remove the seasonality as the standard filtering procedure. As the sample size is small, it is important to use an appropriate statistical procedure to extract information on trend-cycle, seasonality and noise (or measurement error) components systematically from multiple time series data.

In this study, we investigate a new filtering procedure to estimate the hidden states of trend-cycle, which are non-stationary, and to handle multiple time series data, including small sample time series. Kunitomo and Sato (2017), Kunitomo et al. (2018), and Kunitomo et al. (2020) have developed the separating information maximum likelihood (SIML) method for estimating the non-stationary errors-in-variables models. They have discussed the asymptotic and finite sample properties of the estimation of unknown parameters in the statistical models. We utilize their results to solve the filtering problem of hidden random variables and show that they lead to new a way to handle macro-economic time series.

Related literature on the non-stationary economic time series analysis are Engle and Granger (1987) and Johansen (1995), which examined multivariate non-stationary and stationary time series and developed the notion of co-integration without measurement errors. Our problem is related to their work, but it has different aspects, and our focus is on the non-stationary trend-cycle, seasonality and measurement error in the non-stationary errors-in-variable models and their frequency domain analysis. Some related econometric studies on time series in the frequency domain are Baxter and King (1999), Christiano and Fitzgerald (2003) and Müller and Watson (2018). See Yamada (2019) for a survey of related studies, including the well-known Hodrick–Prescot (HP) filter in econometrics.

In statistical multivariate analysis, some studies on the errors-in-variables models are Anderson (1984, 2003) and Fuller (1987); however, they considered multivariate cases of independent observations, and the underlying situation is different from ours.

For statistical filtering methods, Kitagawa (2010) discussed the standard statistical methods already known, including the Kalman-filtering and particle-filtering methods. Although many studies have examined statistical filtering theories, we must exercise caution in analyzing non-stationary multivariate economic time series. See Granger and Hatanaka (1964), Brillinger and Hatanaka (1969) on early studies, and Harvey and Trimbur (2008) on the relationship between HP filter and other methods, for instance. Here we should mention two issues. First, the existing methods often depend on the underlying distributions such as the Gaussian distributions for the Kalman-filtering, and second, they often depend on the dimension of state variables. There may be some difficulty in extending the existing methods to high-dimension cases, even when the dimension is about 10. On the other hand, we expect that our method has robustness properties when we handle small sample economic times series with non-stationary trend-cycle, and stationary seasonality and measurement errors because our method does not depend on the specific distribution as well as the dimension of the underlying random variables. See Kunitomo et al. (2020) for a comparison of small sample properties of the ML (maximum likelihood) and SIML methods for the non-stationary errors-in-variables models, and Nishimura et al. (2019) for an application of financial data smoothing. The most important feature of the present procedure is that it may be applicable to small sample time series data with non-stationary trend-cycle, seasonal and noise components and it has a statistical foundation based on the (real-valued) spectral decomposition of stochastic processes by a (real-valued) Fourier transformation, as we shall explain in Sects. 4 and 5.

In Sect. 2, we give some macro-economic data, which have motivated this present study. In Sect. 3, we define the non-stationary errors-in-variables models and the SIML method. In Sect. 4, we introduce the SIML filtering method. In Sect. 5, we give the statistical foundation of the method and in Sect. 6, we discuss the problem of choosing the number of orthogonal processes and give some numerical examples based on simulation and data. Section 7 contains some applications including an interpretation on the M\(\ddot{u}\)ller–Watson method in econometrics and gives two empirical applications of macro-consumption in Japan. Concluding remarks are given in Sect. 8. The “Appendices A and B” contains some mathematical derivations of our results and figures.

2 Two illustrative examples

In the first illustrative example, we plot the graph of two macro-economic time series in Japan: quarterly (real) consumption and quarterly (real) GDP (1994Q1–2018Q2) as Fig. 1.Footnote 2 It looks like a simple example of linear regression in undergraduate textbooks. However, if we draw the time series sequences of these (original and seasonally unadjusted official) macro-data estimated by the Cabinet office of the Japanese Government as Fig. 2, we find things to be a little more complex than in Fig. 1. There are clear trend-cycle components, seasonal fluctuations, and noise components in two time series data. Although many economists usually use the seasonally adjusted (published) data, which were constructed by using the X-12-ARIMA program in different ministries within the government, the effects of filtering in the program are often unknown. The X-12-ARIMA program uses the univariate reg-ARIMA model, which is a mixture of univariate seasonal ARIMA and linear regression, and it decomposes univariate time series into the trend-cycle, seasonality and noise components as the standard procedure.Footnote 3 In contrast, the DECOMP program, which is explained by Kitagawa (2010), is a possible choice particularly in Japan, uses the univariate AR model and the Kalman filtering technique with AIC, which is based on the Gaussian likelihood. When each time series is handled using different filtering procedures (i.e., different ARIMA models or reg-ARIMA models for instance), it may cause a fundamental problem in their interpretation when the focus is on the relationships among different non-stationary time series.

Figure 3 gives three different macro-consumption data (2002 January–2016 December), which are observed as monthly time series and widely used by economists in Japan to judge the current macro-business condition. The first series is Kakei-Chosa (the data from monthly consumer-survey collected by the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications), the second is Shougyo-Doutai-Statistics (the data from monthly retail constructed by Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI)) and the third is Dai-Sanji-Sangyo-Statistics (the index data on commerce constructed by METI). We note that the data construction processes of these series based on sample surveys are complex in different ministries within the government and each data reflects different aspects of macro-consumption. Although they show similar movements, we observe some differences in trend-cycle, seasonality and noises. Then it may be desirable to unify the monthly consumption series because we want to judge the business condition each month by just observing these data to evaluate the state of the Japanese macro-economy and forming macro-economic policy. Many economists in both governments and private sectors usually use seasonally adjusted data, which were constructed from the quarterly or monthly (original) time series via the univariate X-12-ARIMA seasonal adjustment program. It is important to construct the monthly consumption index, which is consistent with the published quarterly macro-consumption data, which usually reported with substantial time lags. It was one of the motivations to develop our filtering theory.

Some econometricians use the multivariate (parametric) time series models such as VAR (vector autoregressive process) for analyzing macro-economic data and investigating the relationships among them. They may use the seasonally adjusted (official) data, but we need caution to use such data because most published official data are already filtered by the X-12-ARIMA program. When the dimension is more than 2, some difficulties handling trend-cycle, seasonal, and measurement errors at the same time typically arise. A need to handle macro-economic data in a simple non-parametric way motivated us to develop the multivariate non-stationary errors-in-variables models and the filtering method for the hidden state variables with measurement errors in Sects. 3 and 4 (See Morgenstern 1950; Nerlove et al. 1995 for the related issues).

3 Non-stationary errors-in-variables model and SIML

3.1 A simple non-stationary errors-in-variables model and the SIML Method

In this sub-section, we first introduce a simple non-stationary errors-in-variables model with trend and noise components, and explain the SIML method. Then in the next subsection we shall investigate the general framework for non-stationary multivariate time series with trend-cycle, seasonal and measurement-error components.

Let \(y_{j i}\) be the ith observation of the jth time series at i for \(i=1,\ldots,\;n;\,j=1,\ldots ,p\). We set \(\mathbf{y}_i=(y_{1 i},\ldots , y_{p i})^{'}\) be a \(p\times 1\) vector and \(\mathbf{Y}_n=(\mathbf{y}_i^{'})\;(=(y_{i j}))\) be an \(n\times p\) matrix of observations and denote \(\mathbf{y}_0\) as the initial \(p\times 1\) vector and it is fixed. We consider the simple model that the underlying non-stationary trend is \(\mathbf{x}_i^{'}(=(x_{1i},\ldots ,x_{pi}),i=1,\ldots ,n )\) and the noise component is \(\mathbf{v}_i^{'}=(v_{1 i},\ldots , v_{p i})\), which is independent of \(\mathbf{x}_i\). We write

When each pair of vectors \(\varDelta \mathbf{x}_i\) and \(\mathbf{v}_i\) are independently, identically, and normally distributed (i.i.d.) as \(N_p(\mathbf{0},{{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_x)\) and \(N_p(\mathbf{0},{{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_v)\), respectively, we have the observations of an \(n\times p\) matrix \(\mathbf{Y}_n=(\mathbf{y}_i^{'})\) and set the \(np\times 1\) random vector \((\mathbf{y}_1^{'},\ldots , \mathbf{y}_n^{'})^{'}\). Given the initial condition \(\mathbf{y}_0\;(=\mathbf{x}_0)\), we have

where \(\mathbf{1}_n^{'}=(1,\ldots ,1)\) and

We use the \(\mathbf{K}_n\)-transformation that from \(\mathbf{Y}_n\) to \(\mathbf{Z}_n\;(=(\mathbf{z}_k^{'}))\) by

where \({\bar{\mathbf{Y}}}_0= \mathbf{1}_n \cdot \mathbf{y}_0^{'}\),

and

Using the spectral decomposition \(\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}{} \mathbf{C}_n^{' -1} ={\mathbf{P}}_n {\mathbf{D}}_n {\mathbf{P}}_n\) and \(\mathbf{D}_n\) is a diagonal matrix with the k-th element \(d_k= 2 [ 1-\cos \left( \pi \left( \frac{2k-1}{2n+1}\right) \right) ] \;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\), we write

Then the separating information maximum likelihood (SIML) estimator of \({{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_x\) in (2) can be defined by

where we set \(m=m_n=[n^{\alpha }]\;(0<\alpha <1)\).

We need to use m terms in n and the reason for this becomes clear from the frequency domain analysis, which will be explained in Sect. 5.

Kunitomo et al. (2020) discussed the estimation of the variance–covariance matrix \({{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_v\) when \(\mathbf{v}_i\) are i.i.d. vectors and some consistent estimators of \({{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_v\) were developed. As we shall see in Sect. 5, the SIML estimation method is quite robust, even when \(\mathbf{v}_i^{(x)}\) and \(\mathbf{v}_i\) are non-Gaussian stationary processes, and they are serially-correlated.

3.2 General non-stationary errors-in-variables model

To investigate non-stationary trend-cycle component, and stationary seasonality and measurement error component, we consider the general non-stationary multivariate errors-in-variables modelFootnote 4

We take a positive integer \(s\;(s>1)\), N, and \(n=sN\) for the resulting simplicity of exposition and arguments. We explain the general model in three steps.

-

(1)

The trend-cycle factor \(\mathbf{x}_i\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) is a sequence of non-stationary I(1) process that satisfies

$$\begin{aligned} \varDelta \mathbf{x}_i= (1-{{{\mathcal {L}}}}) \mathbf{x}_i=\mathbf{v}_i^{(x)}, \end{aligned}$$(10)with the lag-operator \({{{\mathcal {L}}}}{} \mathbf{x}_i=\mathbf{x}_{i-1},\) \(\varDelta =1-{{{\mathcal {L}}}},\)

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}_i^{(x)}=\sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_j^{(x)}\mathbf{e}_{i-j}^{(x)}, \end{aligned}$$(11)and \(\mathbf{e}_i^{(x)}\) is a sequence of i.i.d. random vectors with \(\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{e}_i^{(x)})=\mathbf{0}\) and \(\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{e}_i^{(x)} \mathbf{e}_i^{(x) '})={{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_{e}^{(x)}\) (positive-semi-definite). The \(p\times p\) coefficient matrices \(\mathbf{C}^{(x)}_j\;(=c_{kl}^{(x)}(j))\) are absolutely summable and \(\Vert \mathbf{C}_j^{(x)}\Vert =O(\rho ^j)\), where \(0\le \rho <1\) and \(\Vert \mathbf{C}_j^{(x)}\Vert =\max _{k,l=1,\ldots ,p}\left| c_{kl}^{(x)}(j)\right|\).

The random vectors \(\mathbf{v}_i\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) are a sequence of stationary I(0) process with

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}_i=\sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_j^{(v)}{} \mathbf{e}_{i-j}^{(v)}, \end{aligned}$$(12)where the \(p\times p\) coefficient matrices \(\mathbf{C}_j^{(v)}\) are absolutely summable and \(\Vert \mathbf{C}_j^{(v)}\Vert =O(\rho ^j)\), where \(0\le \rho <1\) and \(\mathbf{e}_i^{(v)}\) is a sequence of i.i.d. random vectors with \(\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{e}_i^{(v)})=\mathbf{0} ,\) \(\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{e}_i^{(v)} \mathbf{e}_i^{(v) '})={{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_{e}^{(v)}\) (positive definite).

-

(2)

The seasonal factor \(\mathbf{s}_i\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) is a sequence of stationary process,Footnote 5 which satisfies

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{s}_i=\sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_{sj}^{(s)}\mathbf{e}_{i-sj}^{(s)}, \end{aligned}$$(13)where the lag-operator is defined by \({{{\mathcal {L}}}}^s\mathbf{s}_i=\mathbf{s}_{i-s}\;(s\ge 2),\) and \(\mathbf{e}_i^{(s)}\) is a a sequence of i.i.d. random vectors with \(\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{e}_i^{(s)})=\mathbf{0}\) and \(\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{e}_i^{(s)} \mathbf{e}_i^{(s) '})={{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_{e}^{(s)}\) (a non-negative definite matrix). The \(p\times p\) coefficient matrices \(\mathbf{C}_j^{(s)}\) are absolutely summable and \(\Vert \mathbf{C}_j^{(s)}\Vert =O(\rho ^j)\), where \(0\le \rho <1\).

-

(3)

Let \(\mathbf{f}_{\varDelta x}(\lambda ),\) \(\mathbf{f}_v(\lambda )\) and \(\mathbf{f}_{s}(\lambda )\) be the spectral densityFootnote 6 (\(p\times p\)) matrices of \(\varDelta \mathbf{x}_i\), \(\mathbf{v}_i\) and \(\mathbf{s}_i\) (\(i=1,\ldots ,n\)) defined by

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{f}_{\varDelta x}(\lambda )= \left( \sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_j^{(x)}e^{2\pi i\lambda j}\right) {{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_e^{(x)} \left( \sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_j^{(x)'}e^{-2\pi i\lambda j}\right) , \;\;\left( -\frac{1}{2}\le \lambda \le \frac{1}{2}\right) , \end{aligned}$$(14)$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{f}_v(\lambda )= \left( \sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_j^{(v)}e^{2\pi i\lambda j}\right) {{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_e^{(v)} \left( \sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_j^{(v)'}e^{-2\pi i\lambda j}\right) , \;\;\left( -\frac{1}{2}\le \lambda \le \frac{1}{2}\right) , \end{aligned}$$(15)and

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{f}_{ s}(\lambda )= \left( \sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_{sj}^{(s)}e^{2\pi i\lambda sj}\right) {{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_e^{(s)}\left( \sum _{j=0}^{\infty } \mathbf{C}_{sj}^{(s)'}e^{-2\pi i\lambda sj}\right) \;\;\;\left( -\frac{1}{2}\le \lambda \le \frac{1}{2}\right) , \end{aligned}$$(16)where we set \(\mathbf{C}_0^{(x)}=\mathbf{C}_0^{(v)}=\mathbf{C}_0^{(s)}=\mathbf{I}_p\) for normalization and \(i^2=-1\) (see Chapter 7 of Anderson (1971)).

Then the \(p\times p\) spectral density matrix of the transformed vector process of difference series \(\varDelta \mathbf{y}_i\;(= \mathbf{y}_i-\mathbf{y}_{i-1})\) can be represented as

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{f}_{\varDelta y}(\lambda ) =\mathbf{f}_{\varDelta x}(\lambda ) +(1-e^{2\pi i\lambda }) [\mathbf{f}_{s}(\lambda ) + f_v(\lambda )] (1-e^{-2\pi i\lambda }). \end{aligned}$$(17)We denote the long-run variance–covariance matrices of trend-cycle and noise components for \(g,h=1,\ldots ,p\) as

$$\begin{aligned} {{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_{x}=\mathbf{f}_{\varDelta x}(0)\;(=(\sigma _{gh}^{(x)})),\; {{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_v= f_v(0)\;=(\sigma _{gh}^{(v)}), \end{aligned}$$(18)respectively.

One important often neglected issue is that when applying the differencing procedure to non-stationary time series and using the standard statistical method for multivariate stationary time series, there is no guarantee of keeping the relationships among the original time series as they were by using the transformations. Although Engle and Granger (1987) and Johansen (1995) noticed this problem, they did not consider the frequency domain aspect with seasonality and measurement errors (See Hayashi 2000). The SIML filtering approach may shed a new light on the relationships among the time domain and frequency decompositions of non-stationary multivariate time series.

4 The SIML filtering method

4.1 Basic filtering

We introduce the general filtering procedure based on the \(\mathbf{K}_n\)-transformation in (4). When we interpret that the elements of the resulting \(n\times p\) random matrix \(\mathbf{Z}_n\) take real values in the frequency domain, it is easy to understand their roles. Since \(\mathbf{P}_n\) is a kind of real-valued discrete Fourier transformation, vectors \(\mathbf{z}_k\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\) in \(\mathbf{Z}_n\) are asymptotically uncorrelated, as we shall discuss in Sect. 5.1. We investigate the partial inversion of the transformed orthogonal processes. Let an \(n\times p\) matrix

and

where \(\mathbf{X}_n^{*} =(\mathbf{x}_t^{*'})\), \(\mathbf{S}_n =(\mathbf{s}_t^{'})\) and \(\mathbf{V}_n=(\mathbf{v}_t^{'})\) are \(n\times p\) matrices, \(\mathbf{x}_t^{*}=\mathbf{x}_t-\mathbf{x}_0\;(t=1,\ldots , n)\) and \(\mathbf{x}_0=\mathbf{y}_0\) is the initial vector. (We use the subscript t instead of i in this subsection.)

The stochastic process \(\mathbf{Z}_n\) is the orthogonal decomposition of the original time series \(\mathbf{Y}_n\) in the frequency domain and \(\mathbf{Q}_n\) is an \(n\times n\) filtering matrix. Because \(\mathbf{Y}_n\) consist of non-stationary time series, we need a special form of transformation \(\mathbf{K}_n\) in (4). We give explicit forms of two examples, including the trend-cycle filtering and the band filtering procedures. Although there can be many possible filtering procedures within our general framework, it is useful to discuss some linear filtering procedures.

Let an \(n\times n\) diagonal matrix

and \(\mathbf{e}_t^{(n)}=(0,\ldots ,1,\ldots )^{'}\;(t=1,\ldots ,n)\) are the unit vectors and \(w_{t,n}\;(t=1,\ldots ,n)\) are some non-negative constants.

We start with the case when \(w_{t,n}=1\;(t=1,\ldots ,n)\) and we have the identity matrix \(\mathbf{Q}_n=\mathbf{I}_n\). Then we find \(\mathbf{C}_n\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{Q}_n\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}=\mathbf{I}_n\). There can be useful cases and we present two cases as the trend-cycle filtering and the band filtering by choosing \(w_{t,n}=1\) or 0 for some \(t's\). Although the first example could be regarded a special case of the second one, the analysis of trend-cycle component in the first example has an important role in economic time series.

-

(1)

Trend-cycle filtering Let an \(m\times n\;(m<n)\) choice matrix \(\mathbf{J}_m=(\mathbf{I}_m,\mathbf{O})\), and let also \(n\times p\) matrix

$$\begin{aligned} {\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n^{(m)} =\mathbf{C}_n\mathbf{P}_n \mathbf{J}_m^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_m\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}(\mathbf{Y}_n-{\bar{\mathbf{Y}}}_0) \end{aligned}$$(22)and an \(n\times n\) matrix \(\mathbf{Q}_n = \mathbf{J}_m^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_m\;\).

We construct an estimator of \(n\times p\) hidden state matrix \(\mathbf{X}_n^{*}\) only in the lower frequency parts by using the inverse transformation of \(\mathbf{Z}_n\) and deleting the estimated seasonal and noise parts. We denote the hidden trend-cycle state based on m frequencies as

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{X}_n^{(m)} =\mathbf{C}_n\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{J}_m^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_m \mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}{} \mathbf{X}_n^{*}. \end{aligned}$$(23)This quantity is different from \(\mathbf{X}_n^{*}\) because \(\mathbf{x}_t\;(t=1,\ldots ,n)\) in (9) and (10) contains not only the trend-cycle component of \(\mathbf{y}_t\;(t=1,\ldots ,n)\), but also the noise component in the frequency domain, which is different from the measurement noise component \(\mathbf{v}_t\;(t=1,\ldots ,n)\) in (9)–(13). We try to estimate the trend-cycle component of \(\mathbf{x}_t\) by using (22) and recover the trend-cycle component of \(\mathbf{X}_n\) near at the zero frequency because the effects of differenced measurement error noises (\(\mathbf{v}_t-\mathbf{v}_{t-1}\)) are negligible around at zero frequency. This method differs from some existing procedures that consider the decomposition of time series only in the time domain. Our arguments can be justified by using the frequency decomposition of \(\mathbf{y}_t\) and \(\mathbf{r}_t^{(n)}=\varDelta \mathbf{y}_t\) (\(=\mathbf{y}_t-\mathbf{y}_{t-1}\) and \(\mathbf{y}_0\) being fixed), and we shall discuss this issue in Sect. 5.2.

We partition \(\mathbf{P}_n\) into \([m+(n-m)]\times [m+(n-m)]\) matrices as

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{P}_n =\left( \begin{array}{ll} \mathbf{P}_{11}&{}\mathbf{P}_{12}\\ \mathbf{P}_{21}&{}\mathbf{P}_{22}\end{array} \right) \end{aligned}$$and then

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{J}_m^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_m\mathbf{P}_n =\left( \begin{array}{c} \mathbf{P}_{11}\\ \mathbf{P}_{21}\end{array} \right) \left( \mathbf{P}_{11}, \mathbf{P}_{12} \right) =\mathbf{I}_n- \left( \begin{array}{c} \mathbf{P}_{12}\\ \mathbf{P}_{22}\end{array} \right) \left( \mathbf{P}_{21}, \mathbf{P}_{22} \right) . \end{aligned}$$After straightforward calculations (see the “Appendices A and B” for the derivation), the \((j,j^{'})\)th element of \(\mathbf{A}_n=\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{J}_m^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_m\mathbf{P}_n\; \left( =\left( a_{j,j^{'}}^{(n,m)}\right) \right)\) is given by

$$\begin{aligned} a_{j,j}^{(n,m)}= & {} \frac{2m}{2n+1} +\frac{1}{2n+1}\left[ \frac{\sin \frac{2m\pi }{2n+1}(2j-1)}{\sin \frac{\pi }{2n+1}(2j-1)} \right] , \\ a_{j,j^{'}}^{(n,m)}= & {} \frac{1}{2n+1}\left[ \frac{\sin \frac{2m\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)}{\sin \frac{\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)} + \frac{\sin \frac{2m\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})}{\sin \frac{\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})} \right] \;\;(j\ne j^{'}). \nonumber \end{aligned}$$(24)It is possible to evaluate MSE of statistical state vector estimation. Let \({\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n^{(m)} =( {\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_{ni}^{(m)})\) (\({\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_{ni}^{(m)}\) is an \(n\times 1\) vector, \(i=1,\ldots ,p\)) and \(\mathbf{X}_n^{(m)} =(\mathbf{X}_{ni}^{(m)})\) (\(\mathbf{X}_{ni}^{(m)}\) is an \(n\times 1\) vector for \(i=1,\ldots ,p\)). By decomposing \(\mathbf{Y}_n-{\bar{\mathbf{Y}}}_0=\mathbf{X}_n^{*}+\mathbf{S}_n+\mathbf{V}_n\) and \({\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n^{(m)}-\mathbf{X}_n^{*} =\mathbf{C}_n\mathbf{P}_n \mathbf{J}_m^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_m\mathbf{P}_n \mathbf{C}_n^{-1}(\mathbf{S}_n+\mathbf{V}_n)\), we find

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{E}\left[ \left( {\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_{ni}^{(m)}-\mathbf{X}_{ni}^{(m)}\right) \left( {\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_{nj}^{(m)}-\mathbf{X}_{nj}^{(m)}\right) ^{'} \right] =\mathbf{K}_n^{*-1}\mathbf{Q}_n\mathbf{K}_n^{*} {{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_n^{(s+v)}(i,j) \mathbf{K}_n^{*'}{} \mathbf{Q}_n\mathbf{K}_n^{*' -1} , \end{aligned}$$(25)where \(\mathbf{K}_n^{*}=\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}\), \({{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_n^{(s+v)}(i,j)\) is the \(n\times n\) variance–covariance matrix of \(\mathbf{S}_{n i}+\mathbf{V}_{n i}\) and \(\mathbf{S}_{n j}+\mathbf{V}_{n j}\) (\(n\times 1\) vectors for \(i,j=1,\ldots ,p\)), and, \(\mathbf{S}_{n i}\) and \(\mathbf{V}_{n i}\) (\(n\times 1\) vectors) are the ith and jthe column vectors of \(\mathbf{S}_{n}\) and \(\mathbf{V}_{n}\), respectively.

Since (25) does not depend on \(\mathbf{x}_t\), (22) minimizes the MSE with respect to unknown state vector \(\mathbf{x}_t\) to estimate (23) and it is optimal in this sense.

-

(2)

Band filtering We consider a general filtering based on the \(\mathbf{K}_n\) transformation in (4) and use the inversion of some frequency parts of the random matrix \(\mathbf{Z}_n\). The leading example is the analysis of seasonal frequencies in the discrete time series and we take \(s\;(>1)\) being a positive integer as the seasonal lag.

Let an \(m_2\times [m_1+m_2+(n-m_1-m_2)]\) choice matrix \(\mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}=(\mathbf{O},\mathbf{I}_{m_2},\mathbf{O})\) (we take \(m_1+m_2<n\)), and let also \(n\times p\) matrix

and an \(n\times n\) matrix \(\mathbf{Q}_n =\mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}^{'}\mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}\;\).

When we have a particular seasonal frequency \(s\;(>1)\), for instance, we can take \(m_1=[2n/s]-[m/2]\) and \(m_2=m\). We set \(s=4\) for quarterly data and \(s=12\) for monthly data. (We may have many seasonal frequencies in data analysis as pointed out by Granger and Hatanaka (1964) already.)

As in the trend-cycle filtering problem, (26) is the SIML-filtering value for

and it is an estimate of some frequency components of \(\mathbf{x}_t+\mathbf{s}_t\; (t=1,\ldots ,n)\) in (9), (10) and (13). The filtering problem becomes difficult because some frequency component of \(\mathbf{y}_t\) includes not only some component \(\mathbf{x}_t\) at the same frequency, but also some component of the measurement errors at the same frequency.

After straightforward calculations (see the “Appendices A and B”) in this case, the \((j,j^{'})\)th element of \(\mathbf{A}_n=\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}{} \mathbf{P}_n \;\left( =\left( a_{j,j^{'}}^{(n,m_1,m_2)}\right) \right)\) is given by

when \(m_1=0\) and \(m_2=m\), the resulting formula reduces to the trend-cycle filtering case. There are existing filtering procedures having the frequency domain interpretation, but it seems that our procedure differs from some existing literature because of (24) and (28).

It is also possible to evaluate MSE of the state vector estimation in the same way as Case (1). Let \({\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n^{(m_1,m_2)}\) be an estimate of the hidden state as

\(\mathbf{X}_n^{(s, m_1,m_2)} =\mathbf{C}_n\mathbf{P}_n \mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2,n}^{'} \mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2,n}{} \mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n^{-1} (\mathbf{X}_n^{*}+\mathbf{S}_n)\).

By using the similar calculation as Case (1) and the notation of \({{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_n^{(v)}(i,j)\) \(\;(i,j=1,\ldots ,p)\), we find

where \({{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_n^{(v)}(i,j)\) is the \(n\times n\) variance–covariance matrix of \(\mathbf{V}_{ni}\) and \(\mathbf{V}_{nj}\). We use an \((m_2-m_1)\times n\) choice matrix \(\mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}=(\mathbf{O},\mathbf{I}_{m_2-m_1},\mathbf{O})\) and \(\mathbf{Q}_n^{*} =\mathbf{I}_n-\mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_{m_1,m_2}\).

If there are several seasonal frequencies, we need more complicated filtering procedures.

5 On a statistical foundation

5.1 Underlying asymptotic theory

At first glance, the SIML filtering procedure may be regarded as an ad-hoc statistical procedure without any mathematical foundation. However, it has a rather solid statistical foundation.

Let \(\theta _{jk}=\frac{2\pi }{2n+1} (j-\frac{1}{2})(k-\frac{1}{2}),\) \(p_{jk}^{(n)} =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2n+1}}(e^{i\theta _{jk}}+e^{-i\theta _{jk}})\;\) and for \(\mathbf{Y}_n=(\mathbf{y}_i^{'})\) we write \(\mathbf{z}_k^{(n)}\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\) as

which is a (real-valued) Fourier-type transformation and \(\mathbf{y}_0\) is fixed.

Then, we find that \(\mathbf{z}_k^{(n)}(\lambda _k^{(n)})\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\) are the (real-valued) Fourier-transformation of data at the frequency \(\lambda _k^{(n)}\;(= (k-1/2)/(2n+1))\), which is a (real-part of) estimate of the orthogonal incremental process \(\mathbf{z}(\lambda )\;(0\le \lambda \le 1/2)\), which is continuous in the frequency domain.

We shall utilize an asymptotic theory for the stationary linear processes because the time series model defined by (9)–(13) can be regarded as a special case. Let

where \({{\varvec{\mu }}}\) is a constant vector (we assume \({{\varvec{\mu }}}=\mathbf{0}\) for simplicity in this section), \({{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_j\) are \(p\times p\) matrices, and \(\mathbf{w}_i\) are a sequence of mutually independent random variables with \(\mathbf{E}[\mathbf{w}_i]=0,\) \(\mathbf{E}[\mathbf{w}_i\mathbf{w}_i^{'}]={{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_u\;(>0)\). The errors-in-variables model in Sect. 3 implies that the \(p\times p\) matrices \({{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_j\) satisfy \(\sum _{h=0}^{\infty } \Vert {{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_j \Vert <\infty \;\).

We then summarize the useful result on \(\mathbf{z}_k^{(n)}(\lambda _k^{(n)})\). Although it could be regarded as a direct extension of Theorem 8.4.3 of Anderson (1971) for discrete and (ergodic) stationary time series, we could not find the following representation. The proof is given in the “Appendices A and B”.

Proposition 1

Let \(\mathbf{r}_j\;(j=1,\ldots ,n)\) be an ergodic stationary stochastic process given by ( 31 ) with \(\sum _{h=0}^{\infty } \Vert {{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_j \Vert <\infty\) and the fourth order moments of each element of \(\mathbf{w}_i\) are finite.

Let also \(\mathbf{z}_k^{(n)} ({\lambda }_k^{(n)}) =\sum _{j=1}^n p_{jk}^{(n)}{} \mathbf{r}_j\) and \(\mathbf{r}_j\) be an ergodic stationary sequence with \(\mathbf{E}[\mathbf{r}_j]=\mathbf{0}\), \({{\varvec{\varGamma }}}(h)=\mathbf{E}( \mathbf{r}_j \mathbf{r}_{j-h}^{'})\), and the (symmetrized real-valued) spectral density matrix

is the positive definite and bounded (real-valued and symmetrized) spectral matrix. Assume that \(\lambda _k^{(n)}\rightarrow s\), \(\lambda _{k^{'}}^{(n)}\rightarrow t\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty\) for \(0<s<t<\frac{1}{2}\). Then, as \(n\longrightarrow \infty\)

This proposition covers the general model with (9)–(13) with the moment conditions because \(\varDelta \mathbf{y}_i\) are stationary. As the asymptotic variance–covariance matrix of the orthogonal random vectors \(\mathbf{z}_k^{(n)} ({\lambda }_k^{(n)})\) is the (symmetrized real) spectral density matrix, it can be estimated consistently. When we have noise terms as in Sect. 3, it is not possible to estimate the (long-run) variance–covariance matrix \({{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_x\) of trend-cycle component simply by using the differenced time series \(\mathbf{r}_j (= \varDelta \mathbf{y}_j) =\mathbf{y}_j-\mathbf{y}_{j-1}\). It is because

The SIML estimator of \(\mathbf{f}_{SR}(0)\;(=\mathbf{f}_{\varDelta x}(0))={{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_x\) in the general case can be defined by

Then we summarize the basic property of the SIML estimation of \({{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_x\) and the derivation is given in the “Appendices A and B”.

Proposition 2

Assume that the fourth order moments of each element of \(\mathbf{v}_i^{(x)}\) , \(\mathbf{v}_i\) and \(\mathbf{v}_i^{(s)}\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) in ( 9 )–( 13 ) are bounded. We set \(m_n=[n^{\alpha }]\;(0<\alpha <1))\) . Then, as \(n\longrightarrow \infty\)

The above result has some implication on the use of the frequency domain analysis of (non-stationary) multiple time series. For \(0\le \lambda \le \frac{1}{2}\), let the symmetrized (real-valued) spectral density matrix of \(\varDelta \mathbf{y}_j\;(j=1,\ldots , n)\) be \(\;f_{SR,\varDelta y}(\lambda )=(1/2)[f_{\varDelta y}(\lambda ) +{\bar{f}}_{\varDelta y}(\lambda )],\) where \({\bar{f}}(\;\cdot \;)\) is the complex conjugate of f and we have the initial condition \(\mathbf{y}_0\).

Similarly, we find that \(f_{SR,\varDelta x}(\lambda ) =(1/2)[f_{\varDelta x}(\lambda )+{\bar{f}}_{\varDelta x}(\lambda )]\;\),

\(f_{SR,\varDelta s}(\lambda ) =(1/2)(1-e^{2\pi i\lambda }) [f_{s}(\lambda )+{\bar{f}}_{s}(\lambda )](1-e^{-2\pi i \lambda })\;\) and

\(f_{SR,\varDelta v}(\lambda ) =(1/2)(1-e^{2\pi i\lambda }) [f_{v}(\lambda )+{\bar{f}}_{v}(\lambda )](1-e^{-2\pi i \lambda })\).

They are the consequence of (17), (30) and (32) for the symmetrized spectral (real-valued) density matrices.

From this interpretation, it may be easy to find that \(\mathbf{G}_m\) is a consistent estimator of the long-run variance–covariance matrix, which is the spectral density matrix at the zero-frequency \(f_{SR,\varDelta x}(0)\) when we use the \(\mathbf{Z}_n\)-transformation of data.

5.2 Frequency interpretation of SIML-filtering

In the traditional statistical time series analysis for a stationary discrete (vector) process with the (complex-valued) spectral distribution F, it has a representation with right-continuous (complex-valued) orthogonal increments in the frequency domain (see Doob 1953; Brillinger 1980; Brockwell and Davis 1990 for the details). Chapter 7 of Anderson (1971) is informative because of its discussion on real-valued representations although it has only univariate cases. The real-valued multivariate orthogonal processes and the spectral density matrix play important roles in our formulation.

For \(\lambda _k^{(n)}=(k-1/2)/(2n+1)\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\), we rewrite (30) as

Then, by using the inversion transformation with \(\mathbf{P}_n\), we can confirm that

It is another representation of \(\mathbf{R}_n=(\mathbf{r}_i^{(n)'})=\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}{\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n(\mathrm{Q})\) in (19) when \(\mathbf{Q}_n=\mathbf{I}_n\). For any \(s\;(s=1,\ldots ,n)\), \(\mathbf{r}_s^{(n)}\) can be recovered as the weighted sum of othogonal processes \(\mathbf{z}_n (\lambda _k^{(n)})\) at frequency \(\lambda _k^{(n)}\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\). We then, by using \(\mathbf{Y}_n=\mathbf{C}_n\mathbf{R}_n\), recover the non-stationary process \(\mathbf{y}_t^{(n)}\;(t=1,\ldots ,n)\) given the initial condition \(\mathbf{y}_0\) as

Let

Then, when \(\lambda _m^{(n)}\rightarrow \lambda\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty\) (\(0<\lambda <\frac{1}{2}\)), using Lemma 5.1 of Kunitomo et al. (2018), we find

If we set the uncorrelated stochastic process of uncorrelated increments with continuous parameter \(\lambda\) (\(0\le \lambda \le \frac{1}{2}\)) as \(A_n(\lambda )=\sum _{j=1}^n\alpha (\lambda , j-\frac{1}{2})\mathbf{r}_j^{(n)},\) then we find

This corresponds to the continuous representation of a discrete (real-valued) stationary time series in the frequency domain (see Chapter 7.4 of Anderson (1971)). If we write the limit of \(\mathbf{A}(\lambda ) = \lim _{n\rightarrow \infty } \mathbf{A}_n(\lambda )\) (assuming it exists), the (real-valued) spectral distribution matrix \(F_{RS}\) for any \(0\le \lambda _1<\lambda _2\le 1/2\) can be defined as

if \(F_{RS}\) is absolutely continuous and the matrix-valued density process \(f_{RS}(\lambda )\;(0\le \lambda _1<\lambda _2\le 1/2)\) exists.

From (22), we set \({\hat{\mathbf{R}}}_n(m)=({\hat{\mathbf{r}}}_i^{(m,n) '})=\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}{\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n(m)\) and \({\hat{\mathbf{r}}}_i^{(m,n)}\) are \(p\times 1\) vectors for \(i=1,\ldots ,n\). If we write

it is the trend-cycle estimate of the SIML-filtering value for \(\mathbf{r}_s^{(m,n)}\), which is the corresponding element of \(\mathbf{R}_n(m)\;(=\mathbf{C}_n\mathbf{X}_n(m))\). It corresponds to

where \(\mathbf{z}_n^{*}(\lambda _k^{(n)})\) are constructed from the \(n\times p\) hidden states matrix \(\mathbf{X}_n\) instead of the observed \(n\times p\) matrix data \(\mathbf{Y}_n\). Hence (43) is the same as the element of \(\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}{\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n^{(m)}\) in (22), and for \(\lambda _m^{(n)} =m/(2n)\) in the frequency domain it is a discrete version of

Then, (44) is the same as the element of \(\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}\mathbf{X}_n^{(m)}\) in (23), and it has the corresponding (continuous) version in the frequency domain.

Similarly, \({\hat{\mathbf{r}}}_s^{(m_1,m_2,n)} =\sum _{k=m_1+1}^{m_1+m_2} p_{s k} \mathbf{z}_n (\lambda _k^{(n)})\) \(={\hat{\mathbf{r}}}_s^{(m_2,n)}-{\hat{\mathbf{r}}}_s^{(m_1,n)}\;\) (\(s=1,\ldots ,m;\) \(0<m_1<m_2<n\)) can be regarded as a discrete version of

From our interpretation of the SIML filtering we find an interesting representation of (discrete time and real-valued) stationary processes and orthogonal incremental stochastic processes. They are closely related to our method of data analysis for non-stationary vector time series.

5.3 On multivariate filtering methods

There may be a natural question whether any multivariate method of seasonal adjustment or detrending is necessary because the filtered series can depend on the particular choice of co-variables. This may be true if we use some time-domain models such as multivariate ARMA models or other multivariate transformations. An application of Kalman-filtering approach may be an example because it has a multivariate state equation. On the other hand, the application of univariate ARIMA models with X-12-ARIMA has another problem because the filtering result depends on ARIMA for each series and there is no guarantee to keep the original relation among variables at each frequency of our interest. Some filters such as the HP filter use the minimization of univariate criterion function with restriction. Then the filtered result depends on the choice of criteria for each series and there is no guarantee to preserve the original relation among variables at each frequency.

Because our method solely depends on the frequency decomposition, it may be free from these problems. Hence it should be a robust filtering method and with this respect it may be appropriate for analyzing non-stationary multivariate time series.

6 Some simulation and the choice of frequencies

6.1 A guide of choosing frequencies

When we are interested in filtering a non-stationary time series with trend-cycle, seasonality and measurement errors, we need to choose the parameter m. We give a guide to set m in the trend-cycle filtering case for practical purpose. From the discussion of Sect. 5.2, the orthogonal process \(\mathbf{z}_n({\lambda }_k^{(n)})\) corresponds to the frequency \({\lambda }_k^{(n)}=(k-\frac{1}{2})/(2n+1) \;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\). When we are interested in the trend-cycle component, we may only use \({\lambda }_k^{(n)}=(k-\frac{1}{2})/(2n+1) \;(k=1,\ldots , m)\) and then the maximum frequency is approximately

For instance, when we have monthly data over 20 years as an example, we have \(n=240\) and \(s=12\). Since we have seasonal frequencies, we want to find trend-cycle components as business cycles more than 1.5 year, say. Then an appropriate maximum frequency would be \({\lambda }_{max}^{(n)} =1.5/24\) and then we could take \(m^{*}=480\times (1.5/24) =30\).

As another example if we have quarterly data over 30 years, we have \(n=120\) and \(s=4\). Since we have a seasonal frequency, we want to find trend-cycle components as business cycles more than 1.5 years, say. Then an appropriate maximum frequency would be \({\lambda }_{max}^{(n)} =1.5/8\) and then we could take \(m^{*}=240\times (1.5/8) =45\).

If we were interested in the trend-cycle component of the non-stationary time series, these choices might be reasonable candidates.

As we shall see in the next subsection, this point could be checked by simulation for prediction.

6.2 Some simulation

When we have estimates of the state variables \(\mathbf{x}_i^{(m)}\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\), the estimates of error components are \({\hat{\mathbf{v}}}_i^{(m)}=\mathbf{y}_i-{\hat{\mathbf{x}}}_i^{(m)}\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\). Then, an estimated MSE of the one-step ahead prediction errors based on the SIML-smoothing or filtering is given by

where \({{{\mathcal {F}}}}_n\) is the \(\sigma\)-field (information) available at n.

One may try to minimize the estimated h-step prediction MSE by choosing an appropriate m. It may be reasonable to take \(h=2,3\) as short-run prediction and \(h=4, 8\) for long-run prediction from our limited experiments.

We only show a result on the simple trend plus noise model when \(p=1\), \(x_i=x_{i-1}+v_i^{(x)}\) and \(y_i=x_i+v_i\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) with \(v_i^{(x)}\sim N(0,\sigma _x^2)\) and \(v_i\sim N(0,\sigma _v^2)\). The criterion function is the prediction MSE given by

where \({{\hat{x}}}_i^{(m)}\) is the estimate of \(x_i^{(m)}\).

We present the minimum m as \(m^{*}\) based on the trend-cycle filtering as Tables 1, 2 and 3 by taking \(h=2,4,6,8\) and \(n=80, 120, 200, 400\). In our simulations, as n increases, we have larger choice of \(m^{*}\) while \(m^{*}\) decreases as h increases. When we have a long horizon with h, it may be natural to use a small number of lower frequencies, and for a wide range of \(\sigma _x\) and \(\sigma _v\).

6.3 A comparison of the SIML filtering and HP filtering

To characterize some property of the SIML filtering, we give an illustrative example. For this purpose, we take a monthly original consumption data in Sect. 2 (Kakei-Chosa series in Fig. 3) and show the result of the SIML filtering and the HP filtering with two parameter values (\(\lambda\)) as Fig. 4. (We used hpfilter procedure in mFilter R-package for HP filter and took \(m=12\) for the SIML filter, which corresponds to frequencies over 2 year cycles since \(\lambda _{\mathrm{{max}}}^{(n)}=1/24\).) An important point is that when we have strong seasonality in data, the SIML often gives reasonable estimates while the usefulness of HP filter depends on the particular parameter value chosen for \(\lambda\).

Further comparison would be interesting, but it is beyond the scope of this paper.

7 Applications

7.1 An interpretation of Müller and Watson (2018)

Recently, Müller and Watson (2018) have proposed the so-called long-run co-variability of macro-economic time series. They have investigated many non-stationary time series and obtained some empirical findings. In this sub-section, an interpretation of their method will be given as measuring the relationships among long-run trend-cycle in our framework when \(p=2\). Moreover, we obtain an important consequence from Proposition 2 in Sect. 5.1.

In this sub-section, we consider the case of \(p=2\) in (9)–(13). Let \(2\times 2\) matrices \({{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_x=(\sigma _{ij}^{(x)})\), we then define the (long-run) regression coefficient \(\beta =[\sigma _{22}^{(x)}]^{-1} \sigma _{21}^{(x)}\) under the assumption that \(\sigma _{22}^{(x)}>0\). Let also \({{\varvec{G}}}_m(0) =(g_{ij}^{(m)})\), and an \(n\times 2\) matrix

For estimating \({\beta }\), we define

This quantity can be interpreted as the least squares slope of the transformed vector from \(\mathbf{y}_{1n}\) on the transformed vector from \(\mathbf{y}_{2n}\) for an \(n\times 2\) matrix \(\mathbf{Y}_n=(\mathbf{y}_{1n},\mathbf{y}_{2n})\), which is essentially the same as the one proposed by Müller and Watson (2018).Footnote 7 Then, from Proposition 2 in Sect. 5 and its proof in the “Appendices A and B” we immediately obtain the following result.

Proposition 3

In ( 9 )–( 13 ) with \(p=2\) , we assume that the fourth order moments of each element of \(\mathbf{v}_i^{(x)}\) , \(\mathbf{v}_i\) and \(\mathbf{v}_i^{(s)}\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) are bounded, and \({{\varvec{\varSigma }}}_x\) is positive definite.

-

(1)

We fix an m , then \({{{\hat{\beta }}}}\) is not consistent when \(n\rightarrow \infty .\)

-

(2)

Set \(m_n=[ n^{\alpha }]\) and \(0< \alpha <1 ,\) then as \(n\longrightarrow \infty\)

$$\begin{aligned} {{\hat{\beta }}} -{\beta } {\mathop {\longrightarrow }\limits ^{p}} \mathbf{0}. \end{aligned}$$(51)

The second part of this proposition is an extended version of the first part of Theorem 4.1 of Kunitomo and Sato (2017).

A simulation example To illustrate our arguments in Proposition 3, we performed a set of Monte Carlo experiments under the simple situation with \(p=2\) (the replication was 10,00 in each simulation). The model is given by

where we have generated the normal errors \(\mathbf{v}_i^{(x)'}=(v_{1,i}^{(x)},v_{2,i}^{(x)})\), \(\mathbf{v}_i^{'}=(v_{1,i},v_{2,i}),\) \((i=1,\ldots ,n)\) with zero means, variances \(\sigma _j^{(x)}=0.75\) and \(\sigma _j^{(v)}=1.5\;(j=1,2)\), zero covariances and an initial value \(\mathbf{x}_0\).

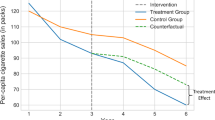

This is a two dimensional I(1)-process, which is not co-integrated, but close to a cointegrated-process. We present the finite sample properties of the (naive) least squares (LS) estimator from the original data, the M\(\ddot{u}\)ller–Watson (MW) estimatot, and the SIML (SIML) estimator from the transformed data.

The simulation results in Tables 4, 5 and 6 are consistent with our arguments in Proposition 3. In the tables, Direct LS stands for the standard regression on \(\mathbf{y}_{1n}\) on \(\mathbf{y}_{2n}\), while MW and SIML stand for Muller-Watson and SIML, respectively. When we have two-dimensional time series and they are not cointegrated, the standard least square method is badly biased. The procedure proposed by Müller and Watson (2018) often gives reasonable results, but its variance does not decrease as the sample size increases. The SIML estimation method has reasonable finite sample properties as well as reasonable asymptotic properties and it is applicable to more general cases.

7.2 Some macro-economic data and constructing a monthly consumption index

As illustrations for the empirical analysis, we have used our filtering method to analyze Japanese quarterly (real) consumption-GDP data as the first example, and three sets of monthly consumption data as the second example, which have been discussed in Sect. 2. “Appendix B” contains all figures in this subsection.

As the first example, the ratio of real GDP and real consumption (quarterly original series) and their time series plots are given in Figs. 1 and 2. They show non-stationarity in their trend-cycle and seasonality as typical macro-economic variables. We then calculate the transformed data using \(\mathbf{P}_n\) (a kind of real Fourier transformation) as Fig. 5 from the original consumption data. In this case, the transformed series gives a wild up and down fluctuation, and trend-cycle and seasonality are sucked. To find seasonal components from the original series, we calculated the realized \(z_k\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\) (Fig. 6) and the empirical cumulative distribution of \(z_k^2\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\) (Fig. 7), which roughly correspond to the normalized and real-valued sample spectral distribution function. Each component of \(\mathbf{z}_k\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\) is an orthogonal decomposition in the frequency domain. Because we have quarterly macro-data, we have a large up and down around (\(\lambda _k^{(n)}=\)) 0.25, which corresponds to the seasonal frequency at \(s=4\). The empirical spectral distribution has an abrupt change at this frequency. From these figures, we can judge that the real Fourier transformation based on \(\mathbf{K}_n\) does give useful information.

As it has been a practice in time series data analysis to use seasonal differencing \(\varDelta _s \mathbf{y}_i=\mathbf{y}_i-\mathbf{y}_{i-s}\) (\(s=4\)) in the Box–Jenkins method, we calculated the real Fourier transformation based on \(\mathbf{P}_n\) (Fig. 8) after seasonal differencing. Although the contribution of the resulting orthogonal process around the seasonal frequency could be significant, there are some rather wild fluctuations on at many other frequencies by using \(\mathbf{P}_n\)-transformation. Because we have some difficulty in interpreting the resulting time series, it may not be possible to justify the seasonal differencing procedure, and we recommend not to use this representation. In the following analysis, we simply use the differencing and then use the frequency domain analysis.

In Fig. 9, we have analyzed real Quarterly-GDP. We show one example with \(m=[n^{0.99}]\) and the deleted seasonal frequency are around 48–52 (48/196–52/196 in [0, 1/2]) and we delete extremely high-frequency part. We deleted only five transformed data around the seasonal frequency and the main intention was to investigate the effect of seasonality with a narrow band. We have taken \(\alpha =0.99\) since we wanted to remove some contribution of high frequency, but we could have used other choices and the results are not much different from Fig. 8 in most cases. We compared the filtered time series using our method and the official (published) seasonally adjusted time series. We found that the differences in two-time series (i.e., the published time series and the SIML filtered time series) are rather small and they are often of negligible magnitude. Although our filtering procedure is simple, this empirical example suggests the usefulness of our method developed in this study.

As the second example, we have analyzed three consumption (monthly) time series and the quarterly consumption time series, which are mentioned in Sect. 2. Then this is an empirical example when \(p=4\) and \(s=12\) with missing observations because the quarterly one series cannot give monthly information. As we have seen in Fig. 3, three monthly consumption series have similarities and some differences in their components. In our example, our goal is to construct the monthly consumption index, which is consistent with the observed quarterly consumption time series in trend-cycle component. Because of non-stationary trend-cycle, seasonal and measurement errors, it may not be obvious to construct a useful consumption index using existing statistical tools.

Let \(Y_i\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) be the target (quarterly) time series and \(Z_{j t}\;(j=1,2,3; t=3(i-1)+l,l=1,2,3)\) be the jth monthly time series (\(t=0\) is the initial period and we fix the initial values \(Y_0, Z_{j 0}\)). Then the criterion function is

where \(\varDelta {{\hat{Y}}}_i^{(T)}={{\hat{Y}}}_i^{(T)}-{{\hat{Y}}}_{i-1}^{(T)},\) (the trend part of the estimated \(\varDelta Y_i\) because we observe quarterly data on \(Y_i\)), \(\varDelta Z_{j t}^{(T)}=Z_{j t}^{(T)}-Z_{j,t-1}^{(T)}\) (the trend parts of \(\varDelta Z_{j t}\)), and \(w_j\;(j=1,2,3)\) are (unknown) weight coefficients and m, \(m_j\;(j=1,2,3)\) are the numbers of trend-cycle filtering. In the above formulation, we need to measure the prediction errors based on differenced data because we have non-stationary trend-cycle component.

Using the least-squares method, we minimized the MSE criterion with respect to the underlying parameters. The estimated \(w_j\;(j=1,2,3)\) are 3.69, 5.19, and 1.64 (while the measurement units are different), but their magnitudes are comparable to the published quarterly consumption level at 2002Q1–2016Q4), which are statistically significant at \(1\%\). We have chosen \(m=29\), \(m_1=36, m_2=23\) and \(m_3=33\). Although it may be possible to use other possibilities, but in our limited experiments, we found some improvements in prediction error over other cases with different combinations of m and \(m_j\;(j=1,2,3)\).

The black curves are the original series and the red curves are the estimated trend curves in Figs. 10 and 11 for two monthly series. By taking relatively large \(m_j\;(j=1,2,3)\), we can recover the cycle components of each series, which are crucial as the indicators of macro-business condition. In Fig. 12, the green curve shows the predicted state value calculated from the latest observed (quarterly) data plus the predicted monthly part based on the estimated parameters. As there is no monthly observation of quarterly published consumption, we draw their latest (quarterly) level with the black curve and the estimated SIML (filtered) values with the red curve.Footnote 8 Overall, we found that while our procedure is much simpler than the X-12-ARIMA seasonal adjustment with reg-ARIMA model, the estimated filtered series are consistent with the (published) quarterly series given the fact we have non-stationary trend-cycle, seasonal and measurement errors components even when we do not have large samples. In Fig. 13, we have drawn the prediction errors in terms of the differenced value \(Y_i\;(i=1,\ldots ,n)\) based on our procedure. This figure illustrates the usefulness of the procedure because the macro-economic time series are non-stationary with measurement errors.

The empirical data analyses in this subsection are presented for illustrations. We are currently investigating the consumption data and the results will be reported on another occasion.

8 Concluding remarks

When the observed non-stationary multivariate time series contain seasonality and noises, it may be difficult to disentangle the effects of trend-cycle, seasonal and measurement errors. In real (seasonally unadjusted) times series, we often observe non-stationary trend-cycle, seasonality and measurement errors while the X-12-ARIMA program in official agencies uses the univariate reg-ARIMA model to remove the seasonality from the original time series. In this study, we investigate a new procedure to decompose time series into non-stationary trend-cycle components, stationary seasonal and noise (or measurement errors) components. The resulting method for non-stationary multivariate series is simple and free from the underlying distributions of components. Hence, it is robust against possible misspecification in the non-stationary multivariate economic time series. An important conclusion is that it is useful to transform the observed time series using the \(\mathbf{K}_n\)-transformation and investigate the transformed \(\mathbf{Z}_n\) series.

In empirical example in Sect. 7, we have illustrated our method to analyze quarterly and monthly macro-consumption data in Japan. We presented a way to construct the monthly consumption index as the second example, which is consistent with the published or official (GDP-)consumption quarterly data. Although the problem is practically complicated, we have shown that our method gives a useful way for a practical purpose.

There can be several further problems. Although it is easy to handle the \(\mathbf{K}_n\)-transformations of non-stationary multivariate time series and construct the transformed \(\mathbf{Z}_n\)-data, there is a non-trivial initial value problem of filtering. Another direction would be to handle some abrupt changes in multiple time series, such as the changes in consumption tax in Japan. Some progress on these problem has been made (Sato and Kunitomo 2020a, b), which will be reported on other occasions. As there are many important empirical applications, we need to develop a systematic statistical procedure.

Notes

Currently, GDP time-series data in Japan are constructed and seasonally adjusted since 1994Q1, although some may think the historical data before 1994 was constructed and measured exactly in the same way. The measuring procedures of official GDP series has been changed several times including the base-year changes. See https://www.esri.cao.go.jp/index-e.html for the detailed explanation of how GDP in Japan is constructed.

In Japan, both the original quarterly series and the seasonally adjusted series of GDP and its major components are regularly published. It differs from macro-data in the US in some aspect.

See Findley et al. (1998) for the detail of X-12-ARIMA program.

It is possible to use the log-transformed data for multiplicative models. It is known that the standard model in X-12-ARIMA is a multiplicative one although it uses moving averages, for instance.

When we assume that \(\varDelta \mathbf{s}_i\) is stationary, most arguments in the following sections would go through. We have omitted its details.

Our notation of spectral density is slightly different from the standard notation used in Anderson (1971). Let \(\mu =2\pi \lambda\) and \(f^A(\mu )\;(-\pi \le \mu \le \pi )\) be the spectral density in Chapter 7 of Anderson (1971). Then, \(f( \lambda )=2\pi f^A(\mu )\;\left(-\frac{1}{2}\le \lambda \le \frac{1}{2}\right)\). The present defition of spectral density corresponds to \(2\pi f^{A}(-\mu )\) in some literature.

In their notation, m corresponds to q, which is fixed. They did use the (differenced) stationary data, and thus, we could interpret that they calculated the linear regression from the filtered data \({\hat{\mathbf{X}}}_n^{*} =\mathbf{P}_n^{ '} \mathbf{J}_m^{'}{} \mathbf{J}_m\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}(\mathbf{Y}_n-\mathbf{Y}_0)\) as a modification of (19) in our notation.

One notable event was the introduction of consumption tax in April 2014 and a sharp deviation of the trend. In the present study, we do not focus on this aspect and it will be in Sato and Kunitomo (2020b).

References

Anderson, T. W. (1971). The statistical analysis of time series. New York: Wiley.

Anderson, T. W. (1984). Estimating linear statistical relationships. Annals of Statistics, 12, 1–45.

Anderson, T. W. (2003). An introduction to multivariate statistical analysis. 3rd edn, Wiley

Baxter, H., & King, R. (1999). Measuring business cycles: Approximate band-pass filters for economic time series. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81–4, 575–593.

Brillinger, D. (1980). Time series: Data analysis and theory, expanded edition. San Francisco: Holden-Day.

Brillinger, D., & Hatanaka, M. (1969). An harmonic analysis of nonstationary multivariate economic processes. Econometrica, 35, 131–141.

Brockwell, P., & Davis, R. (1990). Time series: Theory and methods (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Christiano, L., & Fitzgerald, T. (2003). The band pass filter. International Economic Review, 44–2, 435–465.

Doob, J. L. (1953). Stochastic processes. New York: Wiley.

Durrett, R. (1991). Probability: Theory and examples. Pacific Grove: Duxbury Press.

Engle, R., & Granger, C. W. J. (1987). Co-integration and error correction. Econometrica, 55, 251–276.

Findley, D., Monsell, B., Bell, W., Otto, M., & Chen, B. (1998). New Capabilities and Methods of the X-12-ARIMA Seasonal Adjustment Program. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 16, 127–177.

Fuller, W. (1987). Measurement error models. New York: Wiley.

Granger, C. W. J., & Hatanaka, M. (1964). Spectral analysis of economic time series. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Harvey, A., & Trimbur, T. (2008). Trend estimation and the Hodorick–Prescott filter. Journal of Japan Statistical Society, 38–1, 41–49.

Hayashi, F. (2000). Econometrics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Johansen, S. (1995). Likelihood based inference in cointegrated vector autoregressive models. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Kitagawa, G. (2010). Introduction to time series analysis. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Kunitomo, N., Awaya, N. & Kurisu, D. (2020) Japanese Journal of Statistics and Data Science, 2, 73–101.

Kunitomo, N. & S. Sato (2017). Trend, seasonality and economic time series: The non-stationary errors-in-variables models. SDS-4, MIMS, Meiji University. http://www.mims.meiji.ac.jp/publications/2017-ds.

Kunitomo, N., Sato, S., & Kurisu, D. (2018). Separating information maximum likelihood estimation for high frequency financial data. New York: Springer.

Morgenstern, O. (1950). On the accuracy of economic observations, (1966, revised edition). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Müller, U., & Watson, M. (2018). Long-run covariability. Econometrica, 86–3, 775–804.

Nerlove, M., Grether, D. M., & Carvalho, J. L. (1995). Analysis of economic time series: A synthesis, revised edition. Cambridge: Academic Press.

Nishimura, G. K., Sato, S., Takahashi, A. (2019). Term structure models during the global financial crisis: A parsimonious text mining approach. Asic-Pacific Financial Markets.

Sato, S., & Kunitomo, N. (2020a). On backward filtering for noisy non-stationary time series, MIMS-RBP statistics & data science series (SDS-15). Tokyo: MIMS, Meiji University.

Sato, S. & N. Kunitomo (2020b) Frequency regression and smoothing for noisy non-stationary time series (in preparation)

Yamada, H. (2019) A smoothing method that looks like the Hodrick–Prescott filter (unpublished Manuscript)

Acknowledgements

This is a revised version of the paper (SDS-9, MIMS=RSP Statistics and Data Science Series, Meiji University) presented at the conference “Theory and Applications of Economic and Government Statistics 2019” held at University of Tokyo on January 31, 2019. We thank anonymous referees for their detailed comments, which led to a significant revision of the original paper. We also thank Akihiko Takahashi for giving a valuable suggestion on the SIML filtering method and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing at the initial stage of this work. The research has been supported by JSPS-Grant JP17H02513.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Mathematical derivations

We now present some details of derivations that we have omitted in the previous sections. We refer to Kunitomo et al. (2018) as KSK 2018).

-

(1)

On (24) and (28) When we take \(m_1=0\) and \(m_2=m\), then (28) reduces (24). Hence, we show (28).

For \(\theta _{jk}=\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-\frac{1}{2})(k-\frac{1}{2})\; (j,k=1,\ldots ,n)\), we use the relation that

$$\begin{aligned} \theta _{jk}+\theta _{j^{'},k}=\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)\left( k-\frac{1}{2}\right) ,\; \theta _{jk}-\theta _{j^{'},k}=\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})\left( k-\frac{1}{2}\right) . \end{aligned}$$We then have

$$\begin{aligned}&4 \sum _{k\in I_n^{(1)}}\left[ \cos \theta _{jk}\cos \theta _{j^{'},k}\right] \\= & {} \sum _{k\in I_n^{(1)}}\left[ e^{i(\theta _{jk}+\theta _{j^{'},k})} + e^{-i(\theta _{jk}+\theta _{j^{'},+k})}\right] +\sum _{k\in I_n^{(1)}}\left[ e^{i(\theta _{jk}-\theta _{j^{'},k})} + e^{-i(\theta _{jk}-\theta _{j^{'},k})}\right] , \nonumber \end{aligned}$$(55)where \(\mathbf{I}_n^{(1)}=[1,\ldots ,m]\) (or \(\mathbf{I}_n^{(2)}=[m_1+1,\ldots ,m_1+m_2]\)) is the index set for j and k.

For \(\mathbf{I}_n^{(2)}=[m_1+1,\ldots ,m_1+m_2]\), by rewriting

$$\begin{aligned} \theta _{jk}+\theta _{j^{'},k} =\left(m_1-\frac{1}{2}\right)\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}\left( j+j^{'}-1\right) +\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}\left( j+j^{'}-1\right) (k-m_1), \end{aligned}$$and

$$\begin{aligned} \theta _{jk}-\theta _{j^{'},k} =\left(m_1-\frac{1}{2}\right)\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'}) +\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})(k-m_1), \end{aligned}$$the summation of the first two terms in (55) becomes

$$\begin{aligned} e^{ i(m_1+\frac{1}{2})\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)} \times \frac{1-e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)m_2} }{1-e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)} } +e^{-i(m_1+\frac{1}{2})\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)} \times \frac{1-e^{-i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)m_2} }{1-e^{-i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)} }. \end{aligned}$$For the last two terms in (55), we need to evaluate each term when (1) \(j=j^{'}\) and (2) \(j\ne j^{'}\), separately. Using similar calculations in (55) with the index set \(\mathbf{I}_n^{(2)}\), when \(j\ne j^{'}\), the summation of last two terms becomes

$$\begin{aligned} e^{ i(m_1+\frac{1}{2})\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})} \times \frac{1-e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})m_2} }{1-e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})} } +e^{-i(m_1+\frac{1}{2})\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})} \times \frac{1-e^{-i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})m_2} }{1-e^{-i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j-j^{'})} }. \end{aligned}$$When \(j =j^{'}\), \(\theta _{jk}-\theta _{j^{'},k}=0\) and the summation of last two terms with the index set \(\mathbf{I}_n^{(2)}\) becomes \(2 m_2\). Hence, it is possible to evaluate each terms of (24) and (28). Using the relation

$$\begin{aligned}&e^{ i(m_1+\frac{1}{2})\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1) } \times \frac{1-e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)m_2 } }{1-e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1) } } \\&\qquad \qquad +e^{-i(m_1+\frac{1}{2})\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)} \times \frac{1-e^{-i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)m_2} }{1-e^{-i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j+j^{'}-1)} }. \\= & {} \frac{ e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}\frac{1}{2}(j+j^{'}-1)(m_1) } -e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}\frac{1}{2}(j+j^{'}-1)(m_1+m_2)} }{ e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(-\frac{1}{2})(j+j^{'}-1) } -e^{ i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(\frac{1}{2})(j+j^{'}-1)} } \\&\qquad \qquad + \frac{ e^{ -i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}\frac{1}{2}(j+j^{'}-1)(m_1) } -e^{ -i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}\frac{1}{2}(j+j^{'}-1)(m_1+m_2)} }{ e^{ -i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(-\frac{1}{2})(j+j^{'}-1) } -e^{ -i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(\frac{1}{2})(j+j^{'}-1)} }\; \end{aligned}$$and the corresponding results for \(j-j^{'}\) (there are two cases when (a) \(j=j^{'}\) and (b) \(j\ne j^{'}\)), we obtain the results of (28), and then (24) by using \(\mathbf{I}_n^{(1)}\) instead of \(\mathbf{I}_n^{(2)}\).

-

(2)

The proof of Proposition 1 Essentially, we apply the Central Limit Theorem (Theorem 8.4.3 of Anderson (1971) or Theorem 7.6 of Durrett (1991)) to the sequence of ergodic stationary (discrete) time series. We will give the basic steps of our derivations and mention that the problem here is similar to those explained in Chapters 7–9 of Anderson (1971) in details.

First, we need to show that the resulting variance–covariance terms correspond to those of the limiting Gaussian random variables.

For this purpose, we need to evaluate

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{E}\left[ \mathbf{z}_k^{(n)} ({\lambda }_k^{(n)}) \mathbf{z}_k^{(n)} ({\lambda }_{k^{'}}^{(n)})^{'} \right] =\left[ \frac{1}{2n+1}\right] \sum _{j,j^{'}=1}^n (e^{i\theta _{jk}}+e^{-i\theta _{jk}}) (e^{i\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}}}+e^{-i\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}}}) \mathbf{E}[\mathbf{r}_j\mathbf{r}_{j^{'}}^{'}]. \end{aligned}$$(56)When \(k\ne k^{'}\), we find that the right-hand side terms are bounded by using the straightforward calculations. We notice that the right-hand side consists of sums of four terms associated with

$$\begin{aligned}&(e^{i\theta _{jk}}+e^{-i\theta _{jk}}) (e^{i\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}}}+e^{-i\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}}}) \\&\quad= {} e^{i(\theta _{jk}+\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}})}+e^{-i(\theta _{jk}+\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}})} +e^{i(\theta _{jk}-\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}})}+e^{-i(\theta _{jk}-\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}})} \nonumber \\&\quad= {} (A)+(B)+(C)+(D)\;(\mathrm{, say}). \nonumber \end{aligned}$$(57)Then we find that the sums of each terms associated with (A) and (B) in (56) are bounded, which becomes small when n is large. We write

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{j,j^{'}=1}^n e^{i (\theta _{jk}+\theta _{jk^{'}})} \mathbf{E}[\mathbf{r}_j\mathbf{r}_j^{'}] = \sum _{h=-(n-1)}^{n-1}\sum _{j^{'}\in S(h)} e^{i (\theta _{h+j^{'},k}+\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}}) }{{\varvec{\varGamma }}}(h), \end{aligned}$$(58)where \(S(h)=\{ 1,2,\ldots ,n-h\}\) for \(h\ge 0\) and \(S(h)=\{ 1-h,2-h,\ldots ,n\}\) for \(h< 0\). When \(h\ge 0\) given h, the second sum is given as

$$\begin{aligned}&\sum _{j^{'}=1}^{n-h} e^{i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(h+j^{'}-\frac{1}{2})(k-\frac{1}{2})} e^{i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j^{'}-\frac{1}{2})(k^{'}-\frac{1}{2})} \times {{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (h) \\&\quad= {} \left[ \sum _{j^{'}=1}^{n-h} e^{i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(k+k^{'}-1)(j^{'}-1)} \right] e^{i\frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(h+1/2)(k-\frac{1}{2})+\frac{1}{2}(k^{'}-\frac{1}{2}) } \times {{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (h). \end{aligned}$$When \(h< 0\) given h, the sum can be written

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{j^{'}+h-1=0}^{n+h-1} e^{i \frac{2\pi }{2n+1} \left[ (h+j^{'}-1)(k+k^{'}-1)+\frac{1}{2}\left( k-\frac{1}{2}\right) -\left( h+\frac{1}{2}\right) \left( k^{'}-\frac{1}{2}\right) \right] } \times {{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (h). \end{aligned}$$Because these sums are finite and we have the condition \(\sum _{h=-\infty }^{+\infty } \Vert \varGamma (h) \Vert <+\infty\), the sum with (A) and (B) in (56) become arbitrarily small when n is large. (The terms with (B) are the same as those with (A) except their signs in the exponential parts.)

Second, we need to show that the sums of each terms with (C) and (D) in (56) when \(k=k^{'}\) are dominant terms. We utilized the relation

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{j,j^{'}=1}^n e^{i (\theta _{jk}-\theta _{jk^{'}})} \mathbf{E}[\mathbf{r}_j\mathbf{r}_j^{'}] = \sum _{h=-(n-1)}^{n-1}\sum _{j^{'}\in S(h)} e^{i (\theta _{h+j^{'},k}-\theta _{j^{'}k^{'}}) } \times {{\varvec{\varGamma }}}(h), \end{aligned}$$(59)When \(h\ge 0\) given h, the second sum is given as

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{j^{'}=1}^{n-h} e^{i \frac{2\pi }{2n+1}(j^{'}-1)(k-k^{'})} e^{i \frac{2\pi }{2n+1}\left[ \left( h+\frac{1}{2}\right) \left( k-\frac{1}{2}\right) -\frac{1}{2}\left( k^{'}-\frac{1}{2}\right) \right] } \times {{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (h) \end{aligned}$$and when \(h< 0\) given h, the sum can be written

$$\begin{aligned} \sum _{j^{'}+h-1=0}^{n+h-1} e^{i \frac{2\pi }{2n+1} \left[ (h+j^{'}-1)(k-k^{'})+\frac{1}{2}\left( k-\frac{1}{2}\right) -\left( h-\frac{1}{2}\right) \left( k^{'}-\frac{1}{2}\right) \right] } \times {{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (h). \end{aligned}$$The sums of the above terms are bounded when \(k\ne k^{'}\) by using the same argument as we have (58). (The terms with (D) are the same as those with (C) except their signs in the exponential parts.) On the other hand, when \(k=k^{'}\), \(\sum _{j^{'}=1}^{n-h} e^{i2\pi \frac{k-k^{'}}{2n+1}(j^{'}-1)}=n-h\). Then the dominant sums with (C) and (D) in (56) become

$$\begin{aligned} \left[ \frac{n}{2n+1}\right] \sum _{h=-(n-1)}^{n-1} \left[ \cos 2\pi \frac{k-1/2}{2n+1}h \right] \left[ {{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (h) +{{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (-h) \right] . \end{aligned}$$(60)We note that under the assumption of stationarity of \(\mathbf{r}_j\), it has been known that \(\frac{1}{n}\sum _{j^{'}=1}^n \mathbf{r}_{h+j^{'}}{} \mathbf{r}_{j^{'}}^{'} {\mathop {\longrightarrow }\limits ^{p}} {{\varvec{\varGamma }}}(h).\) (See Chapter 8 of Anderson (1971), and Brockwell and Davis (1990), for instance.)

Third, we consider the situation that \(\lambda _k^{(n)}\rightarrow s\), \(\lambda _{k^{'}}^{(n)}\rightarrow t\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty\) for \(0<s<t<\frac{1}{2}\). Since \(\sum _{h=-\infty }^{+\infty } \Vert \varGamma (h) \Vert <+\infty\) and \(\Vert \varGamma (h) \Vert\) is small as h is large, in the situation that \(\lambda _k^{(n)}\rightarrow \lambda\) for \(0<\lambda < \frac{1}{2}\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty\), we have (32). (We can take k such that \(k/(2n)=\lambda +o(1/n^{\epsilon })\) (\(\epsilon >0\)) such that \(\sum _{\vert h\vert >n^{\epsilon }} \Vert \varGamma (h) \Vert\) is arbitrary small.)

For the asymptotic normality, we set a sequence of random variables

$$\begin{aligned} W_{k,k^{'}}^{(n)}=({{\varvec{\alpha }}}^{'}_1,{{\varvec{\alpha }}}^{'}_2) \left[ \begin{array}{c}{} \mathbf{Z}_n^{'}{} \mathbf{e}_k^{(n)}\\ \mathbf{Z}_n^{'}{} \mathbf{e}_{k^{'}}^{(n)} \end{array}\right] , k,k^{'}=1,\ldots , n, \end{aligned}$$(61)and \(\mathbf{Z}_n=\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{R}_n,\;\mathbf{R}_n=(\mathbf{r}_j^{'})\) (\(n\times p\) matrix), where \({{\varvec{\alpha }}}_i\;(i=1,2)\) are \(p\times 1\) (non-zero) constant vectors and \(e_k^{(n)}=(0,\ldots ,0,1,0\ldots ,0)^{'}\;(k=1,\ldots ,n)\) are \(n\times 1\) unit vectors.

We can also construct a sequence of random variables \(W_{s,t}^{(n)}\) by using \(p_{s, j}^{(n)} =\sqrt{2/(2n+1)}\cos 2\pi s(j-1/2)\) instead of \(p_{jk}^{(n)}\) in \(\mathbf{P}_n\).

Then \(\mathbf{E}\left[ \left| W_{k,k^{'}}^{(n)}-W_{s,t}^{(n)}\right| ^2\right] {\mathop {\rightarrow 0}\limits ^{p}}\) as \(n\rightarrow \infty\) ( \(\lambda _k^{(n)}\rightarrow s\), \(\lambda _{k^{'}}^{(n)}\rightarrow t\) (\(0<s<t<\frac{1}{2}\)).

Finally, we utilize the truncation argument used in the proof of Theorem 8.4.3 of Anderson (1971) and approximate (31) by the (finite order) moving-average representation for a large \(h>0\)

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{r}_i^{(n,h)} ={{\varvec{\mu }}}+\sum _{j=0}^{h} {{\varvec{\varGamma }}}_j\mathbf{w}_{i-j}\; \end{aligned}$$(62)and \(\mathbf{z}_{n,h} ({\lambda }_k^{(n)}) =\sum _{j=1}^n p_{jk}^{(n)}{} \mathbf{r}_j^{(n,h)}\). By applying the standard method of proof in Theorem 8.4.3 of Anderson (1971), i.e., first we fix a \(h>0\) and we show the CLT for \(\mathbf{z}_{n,h} ({\lambda }_k^{(n)})\) and then by taking \(h\rightarrow \infty\) and we can show that the effects of h are negligible because \(\sum _{s=-\infty }^{+\infty } \Vert \varGamma (s) \Vert <+\infty\). \(\square\)

-

(3)

The proof of Proposition 2 Let \(\mathbf{z}_{k}^{(x)}=(z_{k j}^{(x)})\) and \(Z_{k }^{(s+v)}=(z_{k j}^{(s+v)})\) (\(k=1,\ldots ,n\)) be the kth row vector elements of \(n\times p\) matrices

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{Z}_n^{(x)} =\mathbf{K}_n^{*}(\mathbf{X}_n-{\bar{\mathbf{Y}}}_0), \; \mathbf{Z}_n^{(s+v)} =\mathbf{K}_n^{*}(\mathbf{S}_n+\mathbf{V}_n) ,\;\mathbf{K}_n^{*}=\mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n ^{-1}, \end{aligned}$$(63)respectively, where we denote \(\mathbf{X}_n=(\mathbf{x}_{k}^{'})=(x_{k g})\), \(\mathbf{S}_n=(\mathbf{s}_{k}^{'})=(s_{k g})\), \(\mathbf{V}_n=(\mathbf{v}_{k}^{'})=(v_{k g})\), \(\mathbf{Z}_n=(\mathbf{z}_{k}^{'})\;(=(z_{k g}))\) are \(n\times p\) matrices with \(z_{k g}=z_{k g}^{(x)}+z_{k g}^{(s+v)}\). We write \(z_{k g} , z_{kg}^{(x)}, z_{kg}^{(s+v)}\) as the gth component of \(\mathbf{z}_{k}, \mathbf{z}_k^{(x)}, \mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)}\;(k=1,\ldots ,n;g=1,\ldots ,p)\). We use \(z_{k g}^{(f)}\;(f =x,s+v)\) and decompose \({{\hat{\varSigma }}}_{x} - \varSigma _x\;\) (\(=( {{\hat{\sigma }}}_{gh}^{(x)} - \sigma _{gh}^{(x)})_{gh})\) for \(g,h=1,\ldots ,p\)). We re-write

$$\begin{aligned}&\frac{1}{m_n}\sum _{k=1}^{m_n} \mathbf{z}_k\mathbf{z}_k^{'} -\varSigma _{x} \\&= {} \left[ \frac{1}{m_n}\sum _{k=1}^{m_n} \mathbf{z}_k^{(x)} \mathbf{z}_k^{(x)'} - \varSigma _{x} \right] +\frac{1}{m_n}\sum _{k=1}^{m_n} \mathbf{E}\left[ \mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)} \mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)'}\right] \nonumber \\& \quad + \frac{1}{m_n}\sum _{k=1}^{m_n} \left[ \mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)} \mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)'} -\mathbf{E}\left[ \mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)} \mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)'}\right] \right] +\frac{1}{m_n}\sum _{k=1}^{m_n} \left[ \mathbf{z}_k^{(x)}\mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)'} +\mathbf{z}_k^{(s+v)}{} \mathbf{z}_k^{(x)'}\right] . \nonumber \end{aligned}$$(64)Then we will investigate the conditions that three terms except the first one of (64) are \(o_p(1)\) and

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{1}{m_n}\sum _{k=1}^{m_n} \mathbf{z}_k^{(x)}{} \mathbf{z}_k^{(x)'} -\varSigma _{x} {\mathop {\longrightarrow }\limits ^{p}} \mathbf{O}\; \end{aligned}$$(65)as \(m_n\rightarrow \infty \; (n\rightarrow \infty )\). Since \(\varDelta \mathbf{x}_i\) is stationary, it is not difficult to show the second assertion via Chapter 5 of KSK (2018). By using (60), the expected (matrix) value of \((1/m)\sum _{k=1}^{m_n} \mathbf{z}_k\mathbf{z}_k^{'}\) is given by

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{n}{2n+1} \sum _{h=-(n-1)}^{n-1} \left[ \frac{1}{m}\sum _{k=1}^n \cos 2\pi \frac{k-1/2}{2n+1}h \right] \left[ {{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (h) +{{\varvec{\varGamma }}} (-h) \right] . \end{aligned}$$Then by Lemma 5.1 of KSK (2018), the middle sum is \([1/2m]\sin [2\pi m h/(2n+1)]/\sin [ \pi h/(2n+1)]\), which becomes 1 as \(m\rightarrow \infty ,m/n \rightarrow 0\) for a fixed h. Then the limit is \(f_{SR}(0)=\sum _{-\infty }^{+\infty }{{\varvec{\varGamma }}}(h)\) because it is finite. Here we use the notation \(c_{ij}\;(i,j=1,\ldots ,n)\) of Chapter 5 of KSK (2018) as \(c_{ij}=(2/m)\sum _{k=1}^m \theta _{ik}\theta _{jk}\). Then for (non-zero \(p\times 1\)) constant vector \({{\varvec{\alpha }}}\) we can evaluate

$$\begin{aligned} \mathbf{E}\left[ \frac{1}{m_n}\sum _{k=1}^{m_n}({{\varvec{\alpha }}}^{'}\mathbf{z}_k)^2 -{{\varvec{\alpha }}}^{'}\varSigma _{x}{{\varvec{\alpha }}} \right] ^2= & {} \left( \frac{2}{2n+1}\right) ^2\mathbf{E}\left[ \sum _{j,j^{'}=1}^nc_{j j^{'}}{{\varvec{\alpha }}}^{'} (\mathbf{r}_j\mathbf{r}_{j^{'}}^{'}-\mathbf{E}(\mathbf{r}_j\mathbf{r}_{j^{'}}^{'})) {{\varvec{\alpha }}}\right] ^2 \\\le & {} K_1 \left[ \frac{2}{2n+1}\right] ^2 \sum _{j,j^{'}=1}^nc_{j,j^{'}}^2, \end{aligned}$$where \(K_1\) is a positive constant and we used the boundedness of fourth moments. Again by using Lemma 5.2 of KSK (2018), we find that \(\sum _{j,j^{'}=1}^nc_{j,j^{'}}^2=(n+1/2)^2/m\) and we have shown the first assertion as \(m\rightarrow \infty ,m/n \rightarrow 0\).

Next we show that the second, third and fourth terms in the right-hand-side of (64) are asymptotically negligible as \(n\rightarrow \infty\). and we could estimate the variance and covariance of the underlying processes consistently as if there were no seasonal and noise terms

Let \(\mathbf{b}_k= (b_{kj})= \mathbf{e}_k^{'}{} \mathbf{P}_n\mathbf{C}_n^{-1}=(b_{kj})\) and \(\mathbf{e}_k^{(n) '}=(0,\ldots ,1,0,\cdots )\) be an \(n\times 1\) vector. We write \(z_{kg}^{(s+v)}=\sum _{j=1}^n b_{kj}(s_{jg}+{v}_{j g})\) for the seasonal and noise part and use the relation