Abstract

Research indicates that network structure affects the diffusion of a single behavior. However, in many social settings, two or more behaviors may compete for adoption, as in the case of religious competition, social movements and counter-movements, or conflicting rumors. Lessons from one-behavior diffusion cannot be easily applied because the outcome can take the form of one-behavior domination, two behaviors splitting the network, both behaviors occupying a small fraction of the network, or no diffusion. This article tests how three well-known factors of single-behavior diffusion—network transitivity, adoption threshold, and connectedness of early adopters—apply to scenarios of competitive diffusion. Results show that minor differences in initial adopter size tend to magnify, creating a significant “head-start advantage.” Nevertheless, the degree of this advantage depends on the interaction between network transitivity, adoption threshold, and connectedness of initial adopters. The article describes the conditions under which countervailing ties may (or may not) create inequality in behavioral diffusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

Not applicable: this is a simulation study

Code availability

Available in supplementary file.

Notes

I use the term behavior in relation to a wide range of adoption phenomena, such as using technology, wearing a particular fashion item, joining a collective action, and practicing a religion. The key notion is that the behavior is a dichotomous choice: one can either adopt or not adopt.

There are many ways to consider the connectedness of initial adopters. In this article, I connect them as a connected component where all initial adopters are connected as one group through social relationships. Also see section on experiment design.

This is equivalent to “rewiring” the network.

These examples are broadly illustrative rather than strictly true for each case. For instance, although transitivity is generally low in social media networks, it may be high for the social media pages of certain groups where users connect more (e.g., support pages for patients with the same disease).

This refers to the probability of deleting ties from the original network and replacing them with new random ties.

Actors may adopt different behaviors or none at different iterations.

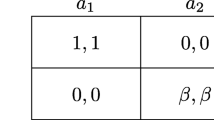

I assume the same threshold and setup of early adopters for both behaviors, rendering the behaviors substitutable.

References

Andrews, K. T. (2002). Movement-countermovement dynamics and the emergence of new institutions: The case of ‘white flight’ schools in mississippi. Social Forces, 80(3), 911–936.

Apt, K. & Evangelos M. 2011. “Diffusion in social networks with competing products.” Pp. 212–23 in Algorithmic Game Theory. Berlin: Springer.

Aral, S., & Van Alstyne, M. (2011). The diversity-bandwidth trade-off. The American Journal of Sociology, 117(1), 90–171.

Baldassarri, D., & Bearman, P. (2007). Dynamics of political polarization. American Sociological Review, 72(5), 784–811.

Barash, V., Cameron, C., & Macy, M. (2012). Critical Phenomena in Complex Contagions. Social Networks, 34(4), 451–461.

Barnett, D., & Njama, K. (1966). Mau mau from within. . New York: Monthly Review Press.

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768.

Berman, B. (1990). Control and crisis in colonial Kenya. . London: James Currey.

Borodin, A., Filmus, Y., & Oren, J. (2010). Threshold models for competitive influence in social networks. In International workshop on internet and network economics (pp. 539-550). Springer, Berlin

Buskens, V., Corten, R., & Weesie, J. (2008). Consent or Conflict: Coevolution of coordination and networks. Journal of Peace Research, 45(2), 205–222.

Burt, R.S. 2001. “Structural holes versus network closure as social capital.” Pp. 31–56 in Social Capital: Theory and Research, edited by N. Lin and K. S. Cook. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Centola, D. (2010). The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science, 329(5996), 1194–1197.

Centola, D. 2018. How behavior spreads: The science of complex contagions. Princeton University Press.

Centola, D. (2013). Homophily, networks, and critical mass: Solving the start-up problem in large group collective action. Rationality And Society, 25(1), 3–40.

Centola, D., & Macy, M. (2007). Complex contagions and the weakness of long ties. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 702–734.

Centola, D., Willer, R., & Macy, M. (2005). The emperor’s dilemma: A computational model of self-enforcing norms. American Journal of Sociology, 110(4), 1009–1040.

Coleman, J.S., Elihu K., & Herbert M. 1966. Medical innovation: A diffusion study. Bobbs-Merrill Co.

Collins, R. (2012). C-Escalation and D-escalation: A theory of the time-dynamics of conflict. American Sociological Review, 77(1), 1–20.

David, P. A. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 332–337.

Esteban, J., & Ray, D. (2008). Polarization, fractionalization and conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 45(2), 163–182.

Fazeli, A., Ajorlou, A., & Jadbabaie, A. (2017). Competitive diffusion in social networks: quality or seeding? IEEE Transactions on Control of Network Systems, 4(3), 665–675.

Fell, D. (2012). Government and politics in Taiwan. . London: Routledge.

Frederiks, M. (2010). Let us understand our differences: Current trends in christian-muslim relations in Sub-Saharan Africa. Transformation Groups, 27(4), 261–274.

González-Bailón, S., Borge-Holthoefer, J., Alejandro R., & Yamir M. 2011. “The Dynamics of Protest Recruitment through an Online Network.” Scientific Reports 197

Gould, R. V. (1991). Multiple networks and mobilization in the paris commune, 1871. American Sociological Review, 56(6), 716–729.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380.

Granovetter, M. (1978). Threshold models of collective behavior. The American Journal of Sociology, 83(6), 1420–1443.

Heckathorn, D. D. (1993). Collective action and group heterogeneity: Voluntary provision versus selective incentives. American Sociological Review, 58(3), 329–350.

Heckathorn, D. D. (1996). The dynamics and dilemmas of collective action. American Sociological Review, 61(2), 250–277.

Hsiao, Y. 2017. “Virtual ecologies, mobilization and democratic groups without leaders: Impacts of internet media on the wild strawberry movement.” Pp. 50–69 in Taiwan’s social movements under Ma Ying-jeou. London: Routledge.

Hu, H. (2017). Competing opinion diffusion on social networks. Royal Society Open Science, 4(11), 171160.

Iannaccone, L. R. (1991). The consequences of religious market structure: Adam smith and the economics of religion. Rationality And Society, 3(2), 156–177.

Johnson, C. (1962). Peasant nationalism and communist power: The emergence of revolutionary China, 1937–1945. Stanford University Press.

Kalyvas, S. N. (2006). The logic of violence in civil war. Cambridge University Press.

Kim, H., & Bearman, P. S. (1997). The structure and dynamics of movement participation. American Sociological Review, 62(1), 70–93.

Kim, H., & Pfaff, S. (2012). Structure and dynamics of religious insurgency: students and the spread of the reformation. American Sociological Review, 77(2), 188–215.

Kim, H., Rhee, E.-Y., & Yee, J. (2008). Comparing fashion process networks and friendship networks in small groups of adolescents. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 12(4), 545–564.

Kitts, J. (2000). Mobilizing in black boxes: Social Networks and participation in social movement organizations. Mobilization, 5(2), 241–257.

Kitts, J.A. & Yongren S. 2018. “Toward an analytical framework of social influence: Behavioral diffusion.” National Academy of Sciences, Exploring the Development of Analytic Frameworks.

Macy, M. W. (1990). Learning theory and the logic of critical mass. American Sociological Review, 55(6), 809–826.

Mahmood, S. (2012). Religious freedom, the minority question, and geopolitics in the middle east. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 54(2), 418–446.

Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and Society, 29(4), 507–548.

Marwell, G., & Oliver, P. (1993). The critical mass in collective action. . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Marwell, G., Oliver, P. E., & Prahl, R. (1988). Social networks and collective action: A theory of the critical mass. III. American Journal of Sociology, 94(3), 502–534.

McPherson, M. (1983). An ecology of affiliation. American Sociological Review, 48(4), 519–532.

McPherson, M. (2004). A blau space primer: Prolegomenon to an ecology of affiliation. Industrial and Corporate Change, 13(1), 263–280.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444.

McVeigh, R., Cunningham, D., & Farrell, J. (2014). Political polarization as a social movement outcome: 1960s klan activism and its enduring impact on political realignment in southern counties, 1960 to 2000. American Sociological Review, 79(6), 1144–1171.

Mercea, D. (2013). Probing the implications of Facebook use for the organizational form of social movement organizations. Information, Communication & Society, 16(8), 1306–1327.

Montalvo, J. G., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2005). Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. The American Economic Review, 95(3), 796–816.

Morris, A. D. (1984). The origins of the civil rights movement. . New York: The Free Press.

Newman, M. E. J., & Watts, D. J. (1999). Renormalization group analysis of the small-world network model. Physics Letters. A, 263(4), 341–346.

Oliver, P., Marwell, G., & Teixeira, R. (1985). A theory of the critical mass. I. Interdependence, group heterogeneity, and the production of collective action. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 522–556.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. . New York: Penguin.

Petersen, A. M., Jung, W.-S., Yang, J.-S., & Eugene Stanley, H. (2011). Quantitative and empirical demonstration of the matthew effect in a study of career longevity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(1), 18–23.

Rogers, E.M. 1995. “Diffusion of innovations: Modifications of a model for telecommunications.” Pp. 25–38 in Die Diffusion von Innovationen in der Telekommunikation, edited by M.-W. Stoetzer and A. Mahler. Berlin: Springer.

Salganik, M. J., Dodds, P. S., & Watts, D. J. (2006). Experimental study of inequality and unpredictability in an artificial cultural market. Science, 311(5762), 854–856.

Schelling, T. C. (1978). Micromotives and macrobehavior. . New York: Norton.

Siegel, D. A. (2009). Social networks and collective action. American Journal of Political Science, 53(1), 122–138.

Soule, S. A., & King, B. G. (2008). Competition and resource partitioning in three social movement industries. American Journal of Sociology, 113(6), 1568–1610.

Taylor, D. G., Lewin, J. E., & Strutton, D. (2011). Friends, fans, and followers: Do ads work on social networks? How gender and age shape receptivity. Journal of Advertising Research, 51(1), 258–275.

Thomas, S. A. (2007). Lies, damn lies, and rumors: An analysis of collective efficacy, rumors, and fear in the wake of Katrina. Sociological Spectrum, 27(6), 679–703.

Valente, T. W. (1996). Social network thresholds in the diffusion of innovations. Social Networks, 18(1), 69–89.

Vise, David. 2007. “The Google Story.” Strategic Direction.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Watts, D. J. (1999). Networks, dynamics, and the small-world phenomenon. American Journal of Sociology, 105(2), 493–527.

Watts, D. J., & Strogatz, S. H. (1998). Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature, 393(6684), 440–442.

Wimmer, A. (2003). Democracy and Ethno-Religious conflict in Iraq. Survival, 45(4), 111–134.

Wojcieszak, M. (2010). ‘Don’t talk to me’: Effects of ideologically homogeneous online groups and politically dissimilar offline ties on extremism. New Media & Society, 12(4), 637–655.

Wood, E. J. (2003). Insurgent collective action and civil war in El salvador. Cambridge University Press.

Zhang, J. & Damon C. 2019. Social networks and health: new developments in diffusion, online and offline. Annual Review of Sociology.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hsiao, Y. Network diffusion of competing behaviors. J Comput Soc Sc 5, 47–68 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-021-00115-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-021-00115-x