Abstract

Misinformation under the form of rumor, hoaxes, and conspiracy theories spreads on social media at alarming rates. One hypothesis is that, since social media are shaped by homophily, belief in misinformation may be more likely to thrive on those social circles that are segregated from the rest of the network. One possible antidote to misinformation is fact checking which, however, does not always stop rumors from spreading further, owing to selective exposure and our limited attention. What are the conditions under which factual verification are effective at containing the spreading of misinformation? Here we take into account the combination of selective exposure due to network segregation, forgetting (i.e., finite memory), and fact-checking. We consider a compartmental model of two interacting epidemic processes over a network that is segregated between gullible and skeptic users. Extensive simulation and mean-field analysis show that a more segregated network facilitates the spread of a hoax only at low forgetting rates, but has no effect when agents forget at faster rates. This finding may inform the development of mitigation techniques and raise awareness on the risks of uncontrolled misinformation online.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acemoglu, D., Ozdaglar, A., & ParandehGheibi, A. (2010). Spread of (mis) information in social networks. Games and Economic Behavior, 70(2), 194–227.

Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. (1947). The psychology of rumor. Oxford, England: Henry Holt.

Anagnostopoulos, A., Bessi, A., Caldarelli, G., Del Vicario, M., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Zollo, F.,& Quattrociocchi, W. (2014). Viral misinformation: the role of homophily and polarization. arXiv:1411.2893.

Andrews, C., Fichet, E., Ding, Y., Spiro, E. S.,& Starbird, K. (2016). Keeping up with the tweet-dashians: The impact of ’official’ accounts on online rumoring. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, CSCW ’16 (pp. 452–465). New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Asch, S. E. (1961). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgements. In M. Henle (Ed.), Documents of gestalt psychology (pp. 222–236). Oakland, California, USA: University of California Press.

Bakshy, E., Hofman, J. M., Mason, W. A., & Watts, D. J. (2011). Everyone’s an influencer: Quantifying influence on Twitter. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, WSDM ’11 (pp. 65–74). New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Bakshy, E., Rosenn, I., Marlow, C.,& Adamic, L. (2012). The role of social networks in information diffusion. In Proceedings of the 21st international conference on World Wide Web (pp. 519–528). ACM.

Bakshy, E., Messing, S., & Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science, 348(6239), 1130–1132.

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. London: Yale University Press.

Bessi, A., Coletto, M., Davidescu, G. A., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2015). Science vs conspiracy: Collective narratives in the age of misinformation. PLoS ONE, 10(2), e0118093.

Borel, B. (2016). The Chicago guide to fact-checking. Chicago, IL, USA: The University of Chicago Press.

Butler, A. C., Fazio, L. K., & Marsh, E. J. (2011). The hypercorrection effect persists over a week, but high-confidence errors return. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(6), 1238–1244.

Centola, D., & Macy, M. (2007). Complex contagions and the weakness of long ties. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 702–734.

Chierichetti, F., Lattanzi, S.,& Panconesi, A. (2009). Rumor spreading in social networks. In Automata, Languages and Programming (pp. 375–386). Springer.

Ciampaglia, G. L., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2015). The production of information in the attention economy. Scientific Reports, 5, 9452.

Ciampaglia, G. L., Shiralkar, P., Rocha, L. M., Bollen, J., Menczer, F., & Flammini, A. (2015). Computational fact checking from knowledge networks. PLoS One, 10(6), e0128193.

Daley, D. J., & Kendall, D. G. (1964). Epidemics and rumours. Nature, 204, 1118.

Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., Stanley, H. E.,& Quattrociocchi W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Dong, X. L., Gabrilovich, E., Murphy, K., Dang, V., Horn, W., Lugaresi, C., et al. (2015). Knowledge-based trust: Estimating the trustworthiness of web sources. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment, 8(9), 938–949.

Factcheck.org. (2017). A project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center. Online. Accessed 28 Oct 2017.

Friggeri, A., Adamic, L. A., Eckles, D.,& Cheng, J. (2014). Rumor cascades. In Proc. Eighth Intl. AAAI Conf. on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM) (pp. 101–110).

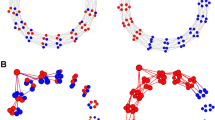

Fruchterman, T. M. J., & Reingold, E. M. (1991). Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Software: Practice & Experience, 21(11):1129–1164.

Funk, S., & Jansen, V. A. A. (2010). Interacting epidemics on overlay networks. Phys. Rev. E, 81, 036118.

Galam, S. (2003). Modelling rumors: the no plane Pentagon French hoax case. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 320, 571–580.

Gleeson, J. P., Ward, J. A., O’Sullivan, K. P., & Lee, W. T. (2014). Competition-induced criticality in a model of meme popularity. Phys. Rev. Lett., 112, 048701.

Howell, L., et al. (2013). Digital wildfires in a hyperconnected world. In Global Risks: World Economic Forum.

Knapp, R. H. (1944). A psychology of rumor. Public Opinion Quarterly, 8(1), 22–37.

Kwak, H., Lee, C., Park, H.,& Moon, S. (2010). What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, WWW ’10 (pp. 591–600). New York, NY, USA: ACM.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444.

Moreno, Y., Nekovee, M., & Pacheco, A. F. (2004). Dynamics of rumor spreading in complex networks. Physical Review E, 69(6), 066130.

Nematzadeh, A., Ciampaglia, G. L., Menczer, F.,& Flammini, A. (2017). How algorithmic popularity bias hinders or promotes quality. e-print, CoRR.

Newman, M. E. J., & Ferrario, C. R. (2013). Interacting epidemics and coinfection on contact networks. PLoS One, 8(8), 1–8.

Nikolov, D., Oliveira, D. F., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2015). Measuring online social bubbles. PeerJ Computer Science, 1, e38.

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2015). The effect of fact-checking on elites: A field experiment on us state legislators. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 628–640.

Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Ubel, P. A. (2013). The hazards of correcting myths about health care reform. Medical Care, 51(2), 127–132.

Onnela, J.-P., Saramäki, J., Hyvönen, J., Szabó, G., Lazer, D., Kaski, K., et al. (2007). Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(18), 7332–7336.

Owens, E., & Weinsberg, U. (2015). News feed fyi: Showing fewer hoaxes (p. 2016). Online. Accessed Jan.

Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. London, UK: Penguin.

Pastor-Satorras, R., Castellano, C., Van Mieghem, P., & Vespignani, A. (2015). Epidemic processes in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys., 87, 925–979.

Qiu, X., Oliveira, D. F., Shirazi, A. S., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2017). Limited individual attention and online virality of low-quality information. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(7), s41562–017.

Rosnow, R. L., & Fine, G. A. (1976). Rumor and gossip: The social psychology of hearsay. New York City: Elsevier.

Snopes.com. (2017). The definitive fact-checking site and reference source for urban legends, folklore, myths, rumors, and misinformation. Online. Accessed 28 Oct 2017.

Sunstein, C. (2002). Republic.com. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tambuscio, M., Ruffo, G., Flammini, A.,& Menczer, F. (2015). Fact-checking effect on viral hoaxes: A model of misinformation spread in social networks. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion (pp. 977–982). International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee.

The Duke Reporters’ Lab keeps an updated list of global fact-checking sites. https://reporterslab.org/fact-checking/. Accessed 29 June 2018.

Times, T. B. (2017). Fact-checking U.S. politics. Online. Accessed 28 Oct 2017.

Weng, L., Flammini, A., Vespignani, A., & Menczer, F. (2012). Competition among memes in a world with limited attention. Scientific Reports, 2, 335.

Wood, T.,& Porter, E. (2016). The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence. e-print, SSRN.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Filippo Menczer and Alessandro Flammini for feedback and insightful conversations. DFMO acknowledges the support from James S. McDonnell Foundation. GLC acknowledges support from the Indiana University Network Science Institute (http://iuni.iu.edu) and from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBTIP2_142353).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix: Mean-field computations

Appendix: Mean-field computations

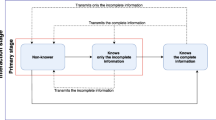

In previous work we showed mean-field analysis for our model on a homogeneous network [44]. Similarly, here we perform a similar analysis for our model on a network segregated in two groups, skeptic and gullible: for each group we have three equations (see Eq. 5) representing the spreading process.

In these equations we can substitute \(s_i(t)\) with \(p_i(t)\) and when \(t \rightarrow \infty \) we can assume \(p_i(t)=p_i(t+1)=p_i(\infty )\) for all \(i \in N\). Hereafter we simplify the notation using \(p_\mathrm{g}^B(\infty )=p_\mathrm{g}^B\) (and analogously for the other cases). Now, let us consider the spreading functions for the gullible agents. Similar equations can be written for the case of skeptic agents. The spreading functions are:

Assuming that all vertices have the same number of neighbors \(\langle k \rangle \), and that these neighbors are chosen randomly, we can write \(n_i^B= s\cdot n^B{i_\mathrm{g}} + (1-s) \cdot n^B_{i_\mathrm{sk}}\), where \(n^B_{i_\mathrm{g}}= \gamma \cdot \langle k \rangle p^B_\mathrm{g}\) and \(n^B_{i_\mathrm{sk}}= (1-\gamma ) \cdot \langle k \rangle p^B_\mathrm{sk}\). Similarly, for \(n_i^F\), we can obtain an expression that is not dependent on i. This simplifies the equations and lets us to simulate the process iterating the application of them until the values of \(p^S_\mathrm{sk},p^B_\mathrm{sk}, p^F_\mathrm{sk}, p^S_{g}, p^B_{g},p^F_{g}\) have reached stability.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tambuscio, M., Oliveira, D.F.M., Ciampaglia, G.L. et al. Network segregation in a model of misinformation and fact-checking. J Comput Soc Sc 1, 261–275 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-018-0018-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-018-0018-9