Abstract

The intensity of cyclones in the Pacific is predicted to increase and sea levels are predicted to rise, so an atoll nation like Tuvalu can serve as the ‘canary in the coal mine’ pointing to the new risks that are emerging because of climatic change. Based on a household survey we conducted in Tuvalu, we quantify the impacts of Tropical Cyclone Pam (March 2015) on households, and the determinants of these impacts in terms of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and responsiveness. Households experienced significant damage due to the storm surge caused by the cyclone, even though the cyclone itself passed very far away (about a 1000 km from the islands). This risk of distant cyclones has been overlooked in the literature, and ignoring it leads to significant under-estimation of the disaster risk facing low-lying atoll islands. Lastly, we constructed hypothetical policy scenarios, and calculated the estimated loss and damage they would have been associated with – a first step in building careful assessments of the feasibility of various disaster risk reduction policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In terms of lowest maximum elevation, Tuvalu is the second lowest-elevation country in the world after the Maldives.

Christenson et al. (2014) found out that in their estimations of population exposed to cyclones, more than half of the top 20 countries world-wide are from the SIDS

The Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) recorded only four storms that affected Tuvalu from 1900 to 2016: the 1972 Tropical Cyclone Bebe, 1990, 1993, and the recent 2015 Tropical Cyclone (TC) Pam. Bebe in 1972 struck down 90% of the houses and killed six people. The other publicly available database of disaster impacts - DesInventar, in contrast, lists tropical cyclones that hit Tuvalu in 1959, 1965, 1972, 1984, 1987, 1990, 1992, 1993 (twice), 1997 (twice), and 2015. Both datasets underestimate disaster damages for Tuvalu for a variety of reasons (see Noy 2016, for details). Kaly and Pratt (2000) reported that out of the 4 Pacific Island Countries they examined (Fiji, Samoa, Tuvalu and Vanuatu), Tuvalu received the highest environmental vulnerability. Of the atoll island countries, Tuvalu, Kiribati, and the Maldives were found to be extremely vulnerable while Marshall Islands and Tokelau were marginally less vulnerable.

This figure is proportionally twice as large as the damage experienced in Japan from the 2011 triple earthquake-tsunami-nuclear accident catastrophe.

The Atoll nations are Tuvalu, Kiribati, Tokelau, Marshall Islands (in the Pacific) and the Maldives (in the Indian Ocean). There are other populated atoll islands in other countries in the Pacific and elsewhere.

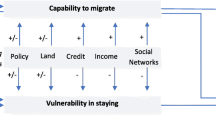

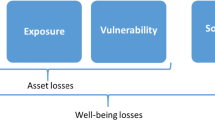

Examples include Clark et al. (1998) which stresses that the two functions of vulnerability are exposure and coping ability. This coping ability is partitioned in their analysis into resistance and resilience. According to Briguglio et al. (2009), risk is determine by exposure and coping ability that are associated with vulnerability and resilience, respectively. Cutter et al. (2008) discusses a framework called the Disaster Resilience of Place (DROP) model which explains and articulates the relationship between vulnerability, resilience and adaptive capacity. However, they defined vulnerability and resilience as the inherent characteristics that create the potential for harm, and the ability to respond and recover from disasters, respectively. There are multiple other frameworks, including many works that emphasized the root causes of vulnerability and the role of poverty in these dynamics; work that is frequently associated with Wisner and his co-authors (e.g., Wisner et al. 2003). See Noy and Yonson (2016) for a survey of the relevant concepts and their measurement.

Previous empirical examinations of direct cyclone impact include, for example, Akter and Mallick (2013), which examine the impacts of a cyclone in Bangladesh, and show the negative impacts of the cyclone on income, employment and access to clean water and sanitation.

The full questionnaire is available for download at: https://sites.google.com/site/noyeconomics/research/natural-disasters.

We used a systematic random sampling approach. We started with the full list of households compiled by the 2012 census. From there, we calculated a skip interval before randomly selecting a starting point from this list of households (made available to us from the Central Statistical Division). We then count down and skipped by the skip interval to identify the list of households to be questioned. The survey questionnaire was approved by the Victoria University of Wellington’s Ethics Committee before the survey was conducted. We encountered some difficulties during the period of the survey around December 2015 as Tuvalu was hit by gale-force winds from TC Ula, preventing ships from going to the outer-islands for almost a week, but the administration of the survey was eventually completed in early 2016. The results presented here were weighted using weights employed by the Central Statistics Division Tuvalu to represent the population of the outer islands.

The survey was conducted using trained interviewers, trained and supervised by one of the authors.

Since there may be differences in the valuation people attached to identical assets, we ask people about the assets they lost, and then convert these to monetary values using market prices. This follows the methodology followed by the Desinventar, the disaster damage dataset collected by the United Nations (UNISDR).

In places with more nuanced topography with potentially lower elevation further inland, distance to the coast and elevation may not be enough. In such case the exact layout of the land will be necessary in order to understand exposure. For Tuvalu, this is unnecessary.

Generally, families (homeowners) in the outer islands rarely move away from their land. Land is very scarce in Tuvalu, and owners are therefore reluctant to leave the family land (lest it be occupied by more distant relatives). It is therefore implausible that the storm triggered any population movement that will bias our sample (as the survey was conducted ex-post).

The consumption bundle of adequate food and non-food estimates a poverty line that is seen as a reasonable minimum expenditure required to satisfy both basic food and non-food needs. We used an estimated food consumption expenditure required for daily calorie energy intake per person that is parallel with the FAO requirement of 2100 kcal (Kcal). This measure is consistent with the official poverty measure used by the Government of Tuvalu. More details regarding poverty measures in Tuvalu are available from Taupo et al. (2016)

We gathered price lists of building materials and furniture from hardware outlets in the capital. We used market prices for estimating equipment values.

These estimated cost of houses, local kitchens, outdoor toilets, water tanks and others were gathered from the Public Works Department (PWD), while the 2015 prices of building materials were collected from the Central Statistics Division and quotations from the 3 main hardware stores (JY Ltd., McKenzie Ltd. and Messamesui Ltd) on Funafuti.

The same principles were also applied for other damages, by tagging a value on an item that is being lost or destroyed, using local market prices to determine their values. If two pigs died as a consequence of the cyclone, then we used a value of AUD 200 if they both weigh 20 kg at a local price of AUD 10 per kg. We used a similar procedure for crops and plants. Local market prices for 2015 were gathered from the Central Statistics Division. Unlike crops and plants that have a shorter lifespan and are harvested and new ones are replanted again in their places, fruit trees provide fruits for a longer period. Valuing their loss is therefore more complex. The only information that was collected is the number of fruit trees and their expected lifetime left in years. For consistency across households, the acquired information together with the local market prices of the fruits were used to calculate the values of fruit trees that were lost.

Poultry (chickens and ducks) was excluded in the calculations of losses since they are mostly left in the open. Unlike pigs, they are easily accounted as they are well kept in pigsties.

Based on the latest GDP figure of AUD 41.2 million in the Government of Tuvalu 2015 National Budget.

Residents of Nukufetau only experienced damage to water storage facilities due to the intrusion of sea water into water storage tanks; and the crops on Nukufetau were mostly destroyed since they are located on a western islet that was directly exposed to the cyclone-generated surges.

Given the small size of these islands, the only significant variability in terms of distance from the storm is across islands rather than across households within an island.

This reliance on distance as a unique indicator of hazard strength is only relevant within the unique context of a distant cyclone hitting an atoll island. A more nuanced hazard model, that also includes wind speed, rainfall, and the topography of the affected area will be required in other instances.

The prevailing winds are easterlies. In islands without lagoons, populations tend to concentrate on the western side of the island (away from the wind), while on islands with lagoons, populations tend to reside on the lagoon side.

Information calculated from the 1991 and 2012 Censuses.

As the hazard we explore here is the storm surge that was generated by the TC, the distinction adopted here between hazard (distance from cyclone) and exposure (elevation and proximity to coast) is arbitrary, and our choice of terminology is not driven by any clear distinction between the two concepts in this specific case.

The conversion rate of 1USD Dollar (US Dollar) = 1.33AUD Dollar (Australian Dollar) was used throughout.

In the 2012 Census, 80% of households reported having access to NBT, the only bank operating in Tuvalu.

This observation is based on conversations with AirWorldwide, the modeler for the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Insurance (PCRAFI) program. We suspect this is the case for other natural hazard risk modelers such as RMS.

Though we cannot rule out the possibility that the availability of early warning is somehow endogenously determined.

The World Bank (2014) estimated Tuvalu’s GDP at AUD 41.7 million, so that total loss and damage to households was about 4.6% of GDP.

References

Akter S, Mallick B (2013) The poverty–vulnerability–resilience nexus: evidence from Bangladesh. Ecol Econ 96:114–124 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2013.10.008

Briguglio L (1995) Small island developing states and their economic vulnerabilities. World Dev 23(9):1615–1632

Briguglio L, Cordina G, Farrugia N, Vella S (2009) Economic vulnerability and resilience: concepts and measurements. Oxf Dev Stud 37(3):229–247. doi:10.1080/13600810903089893

Cavallo E, Noy I (2011) Natural disasters and the economy — a survey. Int Rev Environ Resour Econ 5(1):63–102. doi:10.1561/101.00000039

Christenson E, Elliott M, Banerjee O, Hamrick L, Bartram J (2014) Climate-related hazards: a method for Global assessment of urban and rural population exposure to cyclones, droughts, and floods. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11(2):2169–2192. doi:10.3390/ijerph110202169

Clark GE, Moser SC, Ratick SJ, Dow K, Meyer WB, Emani S et al (1998) Assessing the vulnerability of coastal communities to extreme storms: the case of revere, MA., USA. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Chang 3(1):59–82

Cutter SL, Barnes L, Berry M, Burton C, Evans E, Tate E, Webb J (2008) A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Glob Environ Chang 18(4):598–606. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013

ECLAC (2014) Handbook for disaster assessment. Santiago, Chile: United Nations and economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mastrandrea MD, Mach KJ, Bilir TE (eds) (2014a) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: working group II contribution to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, New York

Field CB, Barros VR, Mastrandrea MD, Mach KJ, Abdrabo M-K, Adger N, … et al (2014b) Summary for policymakers. Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part a: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental panel on Climate Change, p 1–32

Frankenberger T, Nelson S (2013) Background paper for the expert consultation on resilience measurement for food security. FAO & WFP

Gall M (2013) From social vulnerability to resilience measuring progress toward disaster risk reduction. UNU-EHS, Bonn

Hallegatte S (2013) A cost effective solution to reduce disaster losses in developing countries: hydro-meteorological services, early warning, and evacuation. In: Lomborg B (ed) Global problems, smart solutions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 481–499 http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ref/id/CBO9781139600484A019

Haughton J, Khandker S (2009) Handbook on poverty and inequality. The World Bank. http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/978-0-8213-7613-3

Kahn ME (2005) The death toll from natural disasters: the role of income, geography, and institutions. Rev Econ Stat 87(2):271–284. doi:10.1162/0034653053970339

Kaly UL, Pratt C (2000) Environmental vulnerability index: development and provisional indices and profiles for Fiji, Samoa, Tuvalu and Vanuatu : EVI phase II report. SOPAC, Fiji

López-Marrero T, Wisner B (2012) Not in the same boat: disasters and differential vulnerability in the insular Caribbean. Caribb Stud 40(2):129–168

Mitchell T, Jones L, Lovell E, Comba E (2013) Disaster Risk Management in Post-2015 Development Goals. Overseas Development Institute, London

Mechler R, Schinko T (2016) Identifying the policy space for climate loss and damage. Science 354(6310):290–292

Noy I (2016) Natural disasters in the Pacific Island countries: new measurements of impacts. Nat Hazards 84(S1):7–18. doi:10.1007/s11069-015-1957-6

Noy, I., & Yonson, R. (2016). Economic vulnerability and resilience to natural hazards. Oxford Research Encylopedia of Natural Hazard Science doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.76

Schumacher I, Strobl E (2011) Economic development and losses due to natural disasters: the role of hazard exposure. Ecol Econ 72:97–105. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.09.002

Smith, R.-A. J., & Rhiney, K. (2015). Climate (in)justice, vulnerability and livelihoods in the Caribbean: the case of the indigenous Caribs in northeastern St. Vincent Geoforum doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.11.008

Strobl E (2012) The economic growth impact of natural disasters in developing countries: evidence from hurricane strikes in the central American and Caribbean regions. J Dev Econ 97(1):130–141. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.12.002

Taupo T, Cuffe H, Noy I (2016) Household vulnerability on the frontline of climate change: the Pacific atoll nation of Tuvalu. SEF working papers 20/2016 - Victoria University of Wellington. http://www.victoria.ac.nz/sef/research/pdf/SEF-Working-Paper-20-2016.pdf

Tuvalu Government (2015) Rapid assessment report on cyclone pam for Tuvalu. Tuvalu Government, Funafuti

UNDP (2013) Community based resilience assessment (CoBRA) conceptual framework and methodology.Pdf. UNDP drylands development center

UNISDR (2009) UNISDR terminology on disaster risk reduction. United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, Geneva

United Nations (2015) 2015 Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, New York

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2015) Tuvalu: Tropical Pam Situation Report No.1. United Nations

Wisner B, Blaikie P, Cannon T, Davis I (2003) At risk: natural hazards, people’s vulnerability and disasters, 2nd edn. Routledge, New York

Wisner B, Gaillard JC, Kelman I (2011) Framing disaster https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203844236.ch3

World Bank (2014) Hardship and vulnerability in the Pacific Island countries. Washington D.C, The World Bank

World Bank & GFDRR (2013) Building resilience. The World Bank

Yonson R, Gaillard JC, Noy I (2016) The measurement of disaster risk: an example from tropical cyclones in the Philippines. SEF working papers 04/2016 - Victoria University of Wellington. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/4979

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all interviewers for carrying out the field work in Tuvalu, and the Tuvalu Central Statistics Office for their valuable inputs and immense support. Taupo also acknowledges the financial support of NZAID and ADB. We gratefully acknowledge inputs and feedback from participants and reviewers of the 2016 New Zealand Association of Economists conference (Auckland), the 2016 Pacific Update conference (Suva, Fiji), and the 2016 International Conference on Building Resilience (Auckland).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taupo, T., Noy, I. At the Very Edge of a Storm: The Impact of a Distant Cyclone on Atoll Islands. EconDisCliCha 1, 143–166 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-017-0011-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-017-0011-4