Abstract

Rent prices have a strong relationship with economic factors in addition to the structural and environmental characteristics of housing stocks. Previous research demonstrated that impacts of unexpected and sudden circumstances such as war and epidemics on urban housing markets relate to their effects on the economy. Following the first COVID-19 case in Turkey, which was officially announced on 11 March 2020, changes in both housing preferences and economic structure have significantly affected the rental housing market due to the pandemic conditions. To highlight challenges in the rental housing market, this study addressed how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced rental housing prices in 81 provinces of Turkey using the big data set of Endeksa, a private real-estate platform in Turkey. The data set was descriptively analyzed through four main periods identified on the basis of changing COVID-19 pandemic regulations and implementations in Turkey. Average rent prices of Turkish provinces during the identified periods were compared using ArcGIS 10.6. to show how private rent prices changed during the pandemic. The findings demonstrated that the unit rent prices generally increased from March 2020 to December 2021 throughout the whole country. Furthermore, the findings highlighted that while metropolitan cities have the highest unit rent price, the highest rent price rise occurred in provinces located in Central and Eastern Anatolia. This study contributes to the literature on how sudden shocks such as pandemics affect rent prices in free rental markets. In addition, it shows how the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the rental housing market differ from country to country by revealing the increasing trends in Turkey.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Across the world, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in over 542 million confirmed cases and 6.3 million deaths (World Health Organization 2022a). The pandemic has also caused a decreased workforce and dramatic changes in different sectors, such as health, education, finance, and tourism as well as the world economy (Nicola et al. 2020). The pandemic has created uncertainty for the real estate and housing sector due to self-isolation, social distancing, and travel restrictions. In addition to a decline in the number of viewings of rental accommodation because of the infection risk (Nicola et al. 2020), housing choice preferences of individuals have changed with the increase in time spent at home and the popularization of working from home (Nanda et al. 2021; Tomal and Helbich 2022). During the first period of the pandemic, housing investments decreased with increasing risks (Francke and Korevaar 2021). At the same time, different interest rate cuts were provided by many countries during this period (Sahin and Girgin 2021). These changes have affected supply (Chen and Frankin 2020), demand (Kuk et al. 2021), and prices (Li et al. 2022) in the housing markets.

Rental housing is one of the most important components of an effective housing market (Ugurlar and Eceral 2014), because it allows users to move easily in the market with its alternative and flexible structure (Scanlon and Whitehead 2011). However, the dramatic changes in mobility, workforce, and economy during the COVID-19 pandemic have affected the rental housing market in addition to properties for sale. Although previous studies have shown that rent prices have a negative relation with confirmed COVID-19 cases (Tomal and Marona 2021; Trojanek et al. 2021; Li et al. 2022), it is clear that a decline in household income and uncertainty created an insecure environment for tenants. According to Kholodilin (2020), several countries have developed housing policies specially to protect tenants from the negative impacts of the pandemic. For this purpose, governments have suspended or banned evictions, limited the rent increases, and provided rent subsidies to sustain rental market affordability.

The rental housing market in Turkey is shaped by a free-market environment and there is limited regulation to control rent increases and evictions. Rental activities throughout the country are carried out by real-estate offices and individuals without any limitation on the initial rent price. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the government has not developed any specific regulation to reduce negative impacts on tenants. Therefore, the private rental housing market in Turkey provides an example of how a global pandemic will affect rent prices if no policy is developed. This study aims to analyze the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the private rental housing sector in Turkey. For this purpose, the trend of unit rent price change is examined over four periods defined according to the particular national process adopted in response to COVID-19 at any given time. The methodology of the study is based on the descriptive analysis and comparison of the exchange of rental unit prices and unit prices at the provincial scale. Average unit rent prices of the Turkish provinces are compared using ArcGIS 10.6. to show how private rent prices have changed during the pandemic.

This study consists of five main parts. Following the Introduction, Sect. 2 examines the literature regarding private rental housing markets and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Sect. 3, the general characteristics of the rental housing market in Turkey and its current situation as of December 2021 are stated. In Sect. 4, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on rent prices in the provinces of Turkey is analyzed within the framework of the described periods. In Sect. 5, a general evaluation is carried out depending upon the results of the analysis.

2 Private rental housing market and COVID-19

2.1 Private rental housing markets

The rental housing sector is a system where the willing landlord provides the housing supply, and the willing user creates the housing demand. Nowadays, approximately 1.2 billion people globally live in rental housing (Gilbert 2015), because rental markets offer a variety of housing and appeal to different income groups for different reasons. For this reason, rental houses, which provide flexible housing supply to meet the demands and needs of user groups, have an important role in a well-structured housing market.

In the rental housing markets, housing supply is provided by the landlords. Landlords are generally classified as publicly supported organizations, individuals, private institutions and organizations, employers, cooperatives, religious institutions (churches, mosques, etc.), and non-profit institutions and organizations (foundations, etc.), and they can be grouped under two headings as non-profit and for-profit/speculative concerns (Scanlon 2011). While social rental housing is mostly offered to the market by non-profit individuals, institutions, or organizations, such as public bodies, churches, religious institutions, and foundations; the supply of private rental houses may vary from country to country (Scanlon and Kochan 2011; Scanlon 2011).

Housing demand is defined as the willingness of individuals or households to have sufficient income to be able to buy or rent them at a certain price to meet their housing needs (Keleş 2015). In private rental markets, different tenant groups create housing demand based on their wishes, goals, social, demographic, and economic structure like life stage, age, gender, income, household characteristics, and marital status (Scanlon and Kochan 2011).

Rent prices are shaped by the supply and demand relationship in the free market. The structural, qualitative, and quantitative characteristics of the house, neighborhood, and its environmental characteristics are the main determinants for rental housing prices. Previous studies state that the price of a housing unit depends upon the structural and building features of the house (year of construction, construction style, building order, number of floors, etc.), the features of the environment including natural environmental features (topography, sunbathing, scenery, ground, etc.), built environment features (closeness to main transportation and public transportation axes, proximity to social reinforcement areas, etc.), and socio-economic environment features (income level of tenant households, education level, occupation, etc.) (Alkay 2002; Chin and Chau 2003; Malpezzi 2003; Verbrugge et al. 2017; Leung and Yiu 2019).

The rental housing market and rent prices also have an important relationship with the property market for sale. Alp (2019) emphasizes a linear relationship between property housing prices and leasing, and rents increase in parallel with the rise in housing prices. In other words, Tiwari (2000) indicates that as rental housing prices increase, property housing prices also increase. In countries where rent prices are controlled by government regulations, these increases can be kept under control, while in countries where there is no regulation, rents are determined by landlords in the free market. Rent regulations change in line with the development level and political structures of the states. Carmon and Manheim (1979) emphasize that the different social aims of states are one of the important factors affecting the content of housing policies. Policies to regulate rent prices are being developed, especially among social democrats and Continental Europe’s conservative welfare states (Whitehead et al. 2012). For example, in Austria, Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden, initial rental levels for private rental housing are regulated by the government via different approaches. Austria and Germany monitor the initial rent for subsidized rental housing, while Denmark regulates rents for buildings constructed before 1991 (Scanlon 2011). In the Netherlands, the point value system is used to determine the maximum rental value depending on the quality of the residence (Sarıoglu 2007a). In Turkey, which is classified within the Mediterranean welfare countries group due to its structural similarities (Sharkh and Gough 2010; Toprak 2015; Alkan and Ugurlar 2015), the free market determines the initial rent prices, while rent increases are restricted based on the consumer price index.

A possible rent price increase will affect consumers in two ways. These are the rise in the amount of savings required to own a house, and in the share of income allocated to rent. Hike in housing prices causes a rise in the cost of purchasing a new home, both in terms of return and investment, and a decrease in the ownership ratio of low- and middle-income households. At the same time, increase in purchasing costs enhances the expectations of landlords from rental income (Tiwari 2000). Stone (2006) emphasizes that low- and middle-income households, whose access is restricted by rising housing prices, will tend to rent housing and this will cause a growth in rents depending on the demand.

2.2 COVID-19 impact on private rental housing markets

Pandemics have a noticeable impact not only on renters as demanders but also the housing supply. In terms of housing supply, pandemics cause a decrease in the willingness to invest in housing due to the risks they create (Francke and Korevaar 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic is different from disasters where the property is damaged. However, there are clear mechanisms by which both the rental and purchased residential property markets are affected. Kuk et al. (2021) state that rising infection rates can reduce home seekers' willingness to search. A fall in demand could result in both lower prices and reduced listing. Especially after the first COVID-19 outbreak, the listing volume in the rental markets was affected. Chen and Frankin (2020) investigated Manhattan as a case and indicated that the number of properties listed in the first half of 2020 was 26% lower than in the first half of 2019.

On the other hand, there is a strong relationship between housing demand and pandemics due to their impacts on mortality and social and economic structure (Francke and Korevaar 2021). Nanda et al. (2021) state that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in remarkable shifts in individuals’ housing choices to cope with a new lifestyle, particularly during the lockdowns. Especially with the rise of working from home, people started to need additional room to create a workspace at home. Extra space turns into an advantage as it allows options and flexibility to perform various activities not only for work but also leisure, exercise, and relaxation.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, importance of housing came into prominence not only financially but also psychologically and emotionally (Nanda et al. 2021; Waldron 2022). The internal quality of houses, such as indoor air quality, building materials, and having a balcony or garden, are all becoming more essential factors in the housing search process as people spend more time at home. Haaland and Van den Bosch (2015) state that there is limited access to green spaces in compact city areas. Even though the houses in suburban areas are surrounded by recreational places, there is restricted access to social facilities like shopping which gained importance during the COVID-19 pandemic due to lockdowns. However, Liu and Su (2021) state that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a reduction in housing demand in central neighborhoods which have higher population density.

According to statistics of major pandemics in history, housing prices decrease after the outbreak of a pandemic, especially in heavily affected areas (Francke and Korevaar 2021). Li et al. (2022) specified that although there is a negative relation between pandemics and housing prices, the extent and terms of these negative effects differ based on different regions. According to Qian et al. (2021), housing prices can respond to the COVID-19 shock in the long term because of the lower liquidity of residential properties. Even though especially for 2020, it is emphasized that the impact of COVID-19 on housing prices remains uncertain, there are several studies in the literature examining the effect of COVID-19 on housing prices. Del Giudice et al. (2020) investigated the Italian housing market between March and June 2020, and found that there was a 4.16% decline. Similarly, while the Irish residential sales prices fell after March 2020 (Allen-Coghlan and McQuinn 2020), a sudden decline happened in the housing market of the United Kingdom due to restrictive implementations. Moreover, Qian et al. (2021) estimated a decrease of 2.47% in the housing prices in areas of China with confirmed COVID-19 cases, and Huang et al. (2020) found a 2% fall in housing prices between January 2019 and May 2020 in the 64 cities of China.

In contrast, Zhai and Peng (2021) reveal a mean rise of 10% in housing prices between October 2019 and June 2020 in most U.S. states outside central places, while Wang (2021) pointed out that the COVID-19 pandemic has had minimal impact on the U.S. housing sale prices. Furthermore, Yiu (2021) stated that housing prices in several countries increased after the COVID-19 pandemic because of the interest rate cuts which have been implemented by central banks of several countries to support their economies and added that a 1% decrease in the real interest rate gives rise to a 1.5% increase in prices in New Zealand, the U.S., Canada, the UK, and Australia’s housing markets. In 2020, 207 interest rate cuts were implemented by central banks across the globe (Sahin and Girgin 2021) which resulted in homeownership becoming more attractive (Himmelberg et al. 2005).

Turning to rent prices, there are limited studies examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Kuk et al. (2021) found that although there is a negative correlation between rent prices and COVID-19 cases in the Black, Latino, and diverse neighborhoods in the largest metropolitan areas of the United States, white neighborhood rent prices are increasing. Li et al. (2022) state that rents decreased in China’s provincial-level municipalities and provincial capital cities in 2020. While Tomal and Marona (2021) assert that a 6–7% fall in housing rents occurred as a consequence of the first COVID-19 wave and an extra 6.25% decrease in the second wave in Cracow, Trojanek et al. (2021) estimated a 7% decline between March and December 2020 in Warsaw, Poland. Moreover, Tomal and Helbich (2022) emphasized that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in changing rent-determined factors as well as reduced rents in Cracow, Poland.

3 Rental housing market in Turkey

Turkey’s housing policies mainly aim to encourage individuals into homeownership and to promote new housing development (Tekeli 1996; Gökler 2022). Therefore, the rental housing supply is indirectly provided as a part of the housing for sale system (Ugurlar 2013). Units that are purchased for investment purposes or not used by homeowners for individual reasons (relocation, changing housing requirements, etc.) are presented to the rental housing market (Tekeli 2010).

The housing market in Turkey consists of owner-occupied and private rental housing. According to historical housing policies in Turkey, the ‘lojman’ housing produced for civil servants in the 1940s can be said to be the closest housing form to social rental housing. Lojman is defined as a form of rental housing produced by the state or public institutions for civil servants (Ugurlar 2013). In the 1960s, lojman supply by the state became widespread, especially in cities where industrialization was intense and was not preferred by civil servants. However, with the adoption of the neoliberal approach since the 1990s, lojman have been privatized. Therefore, nowadays, the rental housing market has been left to the monopoly of private rental housing.

Today, the rental housing market is shaped within the framework of the Turkish Law of Obligations. Within the scope of the law, rent prices are determined by the lease agreements concluded between the landlord and the tenant (Turkish Law of Obligations 2011). The law ensures that no changes can be made to the detriment of the tenant, except for the determination of the rent, in the lease agreements. Rent increases are determined not to exceed the 12-month average rate in the consumer price index of the previous year. Tenants are given the right to object to both the rent price and the rent increase rate and to file a lawsuit (Turkish Law of Obligations 2011). Under the law, there is no defined rental assistance for tenants. In Turkey, rental assistance is only provided to landlords in urban renewal areas. Within urban renewal projects, tenants are provided with one-time relocation assistance or interest discount in case of buying a house (Law on Transformation of Areas at Disaster Risk 2012).

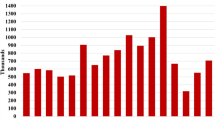

In December 2021, the average unit rent price in Turkey was 17.45 ₺/sqm (Endeksa 2022). Across the country, the average rental housing size is 110 square meters. As of December 2021, the average unit rent price in Turkey had increased by 63.81% compared to the previous year. When the change in the unit rent price by years is analyzed, the average price was 11.72 ₺/sqm in 2019, increased to 12.46 ₺/sqm in 2020, and continued to rise to 15.51 ₺/sqm in 2021 (Fig. 1) (Endeksa 2022). Furthermore, the unit rent prices have increased since November 2019 throughout the country (Fig. 2) (Endeksa 2022).

Source: Produced by authors based on Endeksa 2022

Unit rent price in Turkey (₺/sqm).

Source: Produced by authors based on Endeksa 2022

Unit rent price Change in Turkey (%) (TL).

Surplus housing purchased for investment purposes in Turkey is offered to the rental housing market; therefore, there is a strong relationship between housing sales and the rental housing market. During the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey, no policy or housing rental assistance program has been developed for the private rental housing market. However, in June 2020, with the support of the government, 4 new loan packages were implemented by public banks (Ziraat Bank, Halkbank, and Vakıf Bank) for the transition to the normalization process and the revival of social life. The package provided a low-interest rate (0.64%), no payment up to 12 months, and maturity up to 15 years in the purchase of first-hand/new or second-hand housing (Palabıyık 2020; Birinci 2020). As a result, the package increased house sales after June 2020, which directly altered rental housing supply in the private rental market. (Fig. 3) (TURKSTAT 2022).

Source: TURKSTAT 2022

House sales.

4 Analysis of the change in rent prices affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey

4.1 Data and methodology

According to World Health Organization (WHO) (2022b), in Turkey, there have been 10.735.324 confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to WHO, from January 2020 to January 2022. As Fig. 4 shows, cases peaked in late November 2020, mid-April 2021, and January 2022. During the pandemic, different policies have been developed by the government depending upon the number of cases, deaths, and vaccinated individuals.

To investigate the COVID-19 pandemic process in Turkey, first of all, the regulations are examined to classify the process (Sert Karaaslan 2020; Anadolu Agency 2020; Palabıyık 2020; Birinci 2020; Budak and Korkmaz 2020; T.C. İçişleri Bakanlığı 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2021a, 2021b). After the first official COVID-19 case was announced by the government on March 11, 2020, an attempt was made to keep the pandemic under control with strict regulations until May 2020. In this period, it was ensured that individuals stay at home with practices such as encouraging working from home, curfews, restriction of public transportation use, and online education. As of May 2020, the slogan “mask, distance and cleaning” has been adopted with the Controlled Social Life Program and people have been encouraged to return to social life. In this context, an interest rate reduction program was implemented in June 2020 to support individuals economically.

With the increase in the number of cases in November 2020, the period of New Precautions for COVID-19 Pandemic started. In this period, the curfew practices were expanded once again, and individuals were warned to stay at home again. Although vaccination programs started in this period, it was limited to people at risk and priority groups. As of July 2021, the New Normalization process has been in operation with widespread COVID-19 vaccination. In this period, with the resumption of face-to-face education and the opening of social activity areas, urban life began to return to normal.

In this context, it has been determined that the COVID-19 pandemic process and policies in Turkey consist of four main periods as of 2021, December.

-

1.

First case of COVID-19 and first restrictions (2020, March–2020, May)

-

2.

Controlled social life (Kontrollü Sosyal Hayat) (2020, May–2020, November)

-

3.

New precautions for COVID-19 pandemic (Koronavirüs Salgını Yeni Tedbirler) (2020, November–2021, July)

-

4.

New normalization (2021, July–2021, December).

The Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT) is the primary data provider in Turkey, and according to Sarıoglu Erdogdu (2022), it has limited housing data because of the Turkish government’s market-based housing approach. She emphasizes that there is no continuous housing policy in Turkey, so the government has not needed to create a comprehensive housing data source to date. Moreover, the geographical coverage of housing data is another significant problem in the country and there are almost no provincial-based data for housing research (Sarıoglu 2007b).

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant alterations in the rental housing market across the country. Therefore, this research was conducted on the provincial scale for 81 provinces of Turkey. The monthly unit rent prices data from January 2019 to December 2021 were collected from Endeksa’s big data set (Endeksa 2022) to investigate the evolution of Turkey’s private rental prices. Endeksa is an online real-estate data platform providing cutting-edge machine learning technology-enhanced real-estate data spatially produced with the data collected by field experts and various resources. Currently, Endeksa is the only open-data source for the province scale housing research, and the company does not share any information about what percent of the actual market is reflected in the database. The methodology of this paper is based on the descriptive analysis of the average unit rent price changes over the defined periods and the results were evaluated by graphing in Excel and mapping in ArcGIS 10.6. The most important limitation of the research is that the relationship between unit rent price changes and other variables cannot be examined due to the lack of data at the provincial scale in Turkey, and therefore, it remains descriptive evidence.

4.2 Findings

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the average unit rent price between 2019 January and 2020 March was 11.72 ₺/sqm in Turkey. The highest unit rent prices, respectively, were in Mugla, Istanbul, Izmir, and Antalya (Fig. 5). With the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in Turkey, called the First Case of COVID-19 and First Restrictions period between 2020 March and 2020 May, the average unit rent price in Turkey was 11.96 ₺/sqm and the highest unit rent prices, respectively, were in Mugla (18.29 ₺/sqm), Istanbul (15.57 ₺/sqm), Antalya (14.45 ₺/sqm), and Izmir (13.95 ₺/sqm) (see Fig. 6). However, when the unit rent price change is analyzed compared with the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively, Tunceli (41.22%), Elazig (25.70%), Nevsehir (22.77%), and Kars (22.31%) have the highest increment ratio. Furthermore, except for Nigde (− 2.10%), Gumushane (− 3.41%), and Hakkari (− 29.47%), the rent prices in all provinces of Turkey increased during that period (see Figs. 6, 7). In contrast, previous studies show that the shock effect of historical pandemics reduced housing prices in the first place. However, after the first outbreak, rent prices in the private rental housing market in Turkey, which is shaped by a free-market environment, rose across the country, with the exception of a few provinces. When the unit price change trend (see Fig. 7) and the number of confirmed cases (see Fig. 4) are examined mutually, there is no parallelism. According to Aksoy Khurami and Özdemir Sarı (2022), the economic crisis in 2018/19 had a more negative impact on housing markets than the pandemic. Similarly, it is estimated that the rent increases experienced in this period may be due to the long-term effects of the 2018/19 crisis.

From the Controlled Social Life period (between 2020 May and 2020 November) to New Precautions for COVID-19 Pandemic period (between 2020 November and 2021 July), the average unit rent price in Turkey increased from 12.61 to 14.10 ₺/sqm. Similarly, the highest unit rent prices were in Mugla (19.31–20.39 ₺/sqm), Istanbul (16.63–19.58 ₺/sqm), Antalya (14.81–16.22 ₺/sqm), and Izmir (14.55–16.15 ₺/sqm) during both terms (see Fig. 6). While Tunceli (24.24%), Kahramanmaras (13.34%), Elazig (12.01%), and Batman (11.80%) have, respectively, the highest increase ratio compared with the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic, the unit rent price in Isparta (− 0.13%) and Hakkari (− 5.07%) declined (see Figs. 6, 7). On the other hand, the rent prices climbed in the whole country in comparison with Controlled Social Life period, when the rent prices in Tunceli (28.33%), Nevsehir (27.87%), Mersin (27.51%), and Diyarbakir (27.09%) saw an overall increase (see Figs. 6, 7). In the fourth period of the COVID-19 pandemic, called the New Normalization (from 2021 July to 2021 December) the average unit rent price in Turkey was 16.63 ₺/sqm, and likewise, the highest unit rent prices were in Mugla (23.83 ₺/sqm), Istanbul (22.68 ₺/sqm), Antalya (20.70 ₺/sqm), and Izmir (19.21 ₺/sqm) (see Fig. 6). In that period, the rent prices in Nevsehir (38.38%), Mus (37.53%), Tekirdag (32.10%), and Kayseri rose rapidly, while they dropped in Elazig (-0.22%) and Hakkari (− 0.21%) (see Figs. 6, 7).

While there were no drastic changes in the number of confirmed cases during the Controlled Social Life period (see Fig. 4), maximizing the housing sales had a noticeable impact on the rental housing supply, and thus the rent prices. Although there were ups and downs in the case numbers during the New Precautions for COVID-19 Pandemic, the increase in rent prices across the country similarly may be related to housing sales. In this period, a rise is observed in all of the small city housing markets in the east. While increases continued in some provinces in the New Normalization, there was a decrease in the increment rates and/or in prices in some provinces. The policies that developed with New Normalization and affect people’s mobility, such as the restart of face-to-face education and a decline in remote working, are considered the main causes of this change in contrast to the number of confirmed cases.

According to Fig. 7, it is clear that there is no stability in the unit rent prices in Turkey. While unit rent prices throughout the country had risen slightly, the rate of increase started to climb after the COVID-19 outbreak. While there is no common breaking point for all provinces as regards to the general trend, the rate of increase started to climb rapidly at the end of the New Precautions for COVID-19 Pandemic and during the New Normalization periods. Contrary to the general trend, unit rent prices decreased in Hakkari, except for during the New Precautions for COVID-19 Pandemic period, while the average rental values remained at the lowest level in Nigde and Sirnak. Rent prices in Elazig, which increased rapidly with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, started to decrease during the New Normalization period.

5 Conclusion

There has been no steady increase or decrease in the number of confirmed cases following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. During the First Case of COVID-19 and First Restrictions period, the number of cases increased and after a while decreased slightly. After that, the number of cases, which seemed to be stable since the middle of the Controlled Social Life period, showed a rapid increase and then stabilized. This is due to the government's official announcement of the total number of confirmed cases. The cases, which were also fluctuating during the New Precautions for the COVID-19 Pandemic and New Normalization periods, reached their peak as of December 2021. When the relationship between the confirmed cases and the trend in unit rent prices is examined, it is observed that rent prices in Turkey generally increased after the COVID-19 pandemic, unlike the effect of historical pandemics on housing markets. Although there is no parallel relationship with the number of cases, it is estimated that the rise in unit rent prices in many provinces after the New Precautions for the COVID-19 Pandemic period was also influenced by the uncertain environment created by the pandemic.

Mugla, Istanbul, Antalya, and Izmir are the provinces with the highest unit rent prices across the country, both before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the analyzed periods. The unit rent prices in these cities grew slightly. The metropolitan cities of Turkey like Istanbul and Izmir have several universities which cause an increment in the student population during education terms. However, online education was adopted in the education system in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic which meant that students could follow their classes from their hometown. Therefore, the reduced student population in metropolitan cities may have resulted in declined housing demand and this can be a reason for slow or stabilized unit rent price increase.

While it is observed that there were drastic increases in provinces like Tunceli and Nevsehir located in Central and Eastern Anatolia, in some cities, such as Hakkari, the unit rent prices went down in all except for the New Precautions for the COVID-19 Pandemic period. Rental housing is mostly preferred by civil servants, especially in the eastern part of Turkey’s provinces. If these workers postponed their viewings of potential housing or delayed the moving process due to the popularization of working from home, they may have caused a fall in rental housing demand. Furthermore, the level of preferability based on personal reasons for the Anatolian cities can be another factor. These diversifying housing demands may have resulted in a different increase or decrease in unit rent price change ratios.

During the New Precautions for COVID-19 Pandemic period, there was a rise in rent increase rates in all provinces throughout the country. This situation could be a consequence of interest rate reductions for selling houses. Lowering interest rates can encourage individuals to buy a house and there has been an increase in home sales in Turkey after the interest rate cuts. The houses listed in the rental housing market in Turkey are generally unused houses due to differing individual needs. In other words, there is no direct rental housing supply across the country. Therefore, the decline in interest rates directly affects the number of properties listed as rental houses. The withdrawal of these listed units from the market will cause an increase in rent prices if the housing demand remains stable or increases in the free-market environment.

The pandemic has impacted the private rental housing market around the world. This impact is observed at various scales due to infection rates, mobility restrictions, increasing risks, decreasing willingness to search for homes, etc. Therefore, the literature shows that the direct effect of the pandemic results in a decrease or change in demand and thus a decrease in supply. Previous studies demonstrate that, historically, pandemics impacted housing prices negatively and it took a long time for the markets to adjust. However, in the COVID-19 pandemic, the prices dropped or stagnated during the first couple of months as a shock response but then, with a global interest cut intervention, the tides of the market turned with increasing prices. It implies that price changes in the rental housing market are more of an outcome of demand and supply changes in the overall housing market impacted by interest rates, instead of the pandemic’s first-hand social and health impacts.

Despite data limitations, this study has revealed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the rental housing prices in Turkey. Compared to previous studies in the literature, although the average unit rent price in Turkey tended to decrease before the pandemic, it increased after the COVID-19 outbreak. From this perspective, this contributes to the literature on how pandemics can affect rent prices when governments adopt market-oriented approaches. Even though this paper does not cover the current situation, unit rental prices continue to rise in Turkey in 2022. The government has limited the rent increase rates to 25% for the next year as of July 2022. However, it is observed that the lack of a restriction on the rent price determination process causes the initial rents to sharply increase in the market with corresponding tension in the landlord–tenant relationship. In addition, a social housing project is currently being developed by the government as a solution to the current rental housing crisis. It is clear that solutions to the rental housing crisis, which deepened with the pandemic in Turkey, are still sought through policies developed for homeownership. However, it is very important to develop comprehensive governmental data sets for the rental housing markets in Turkey and to test the reasons for the rental housing crisis with different factors in future studies.

References

Abu Sharkh M, Gough I (2010) Global welfare regimes: a cluster analysis. Global Social Policy 10(1):27–58

Anadolu Agency AA (2020) Cumhurbaşkanı Erdoğan: Normal hayata dönüşü kademe kademe başlatacağız. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/turkiye/cumhurbaskani-erdogan-normal-hayata-donusu-kademe-kademe-baslatacağız/1828617. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

Aksoy Khurami E, Özdemir Sarı ÖB (2022) Trends in housing markets during the economic crisis and COVID-19 pandemic: Turkish case. Asia Pac J Reg Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-022-00251-w

Alkan L, Ugurlar A (2015) Türkiye’de konut sorunu ve konut politikalari. Kent Arastirmaları Enstitüsü, Rapor 1, pp 1–62

Alkay E (2002) Hedonik Fiyat Yöntemi ile Kentsel Yeşil Alanların Ekonomik Değerlerinin Ölçülmesi (Doktora tezi). İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, İstanbul

Allen-Coghlan M, McQuinn KM (2020) The potential impact of COVID-19 on the Irish housing sector. Int J Hous Mark Anal 14:636–651

Birinci M (2020) Kamu bankalarından 4 yeni kredi destek paketi. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/kamu-bankalarindan-4-yeni-kredi-destek-paketi/1860427. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

Budak F, Korkmaz Ş (2020) COVID-19 pandemi sürecine yönelik genel bir değerlendirme: Türkiye örneği. Sosyal Araştırmalar Ve Yönetim Dergisi 1:62–79

Carmon N, Mannheim B (1979) Housing policy as a tool of social policy. Soc Forces 58(1):336–354

Chen S, Franklin S (2020) Real estate prices fall sharply in New York. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/02/realestate/coronavirus-real-estateprice-drop.html?action=click&module=Latest&pgtype=Homepage. Accessed 2 July 2020

Chin TL, Chau KW (2003) A critical review of literature on the hedonic price model. Int J Hous Sci Appl 27(2):145–165

Del Giudice V, De Paola P, Del Giudice FP (2020) COVID-19 infects real estate markets: short and mid-run effects on housing prices in Campania region (Italy). Social Sciences 9(7):114

Endeksa (2022) Retrieved from https://www.endeksa.com/tr/analiz/turkiye/endeks/kiralik/konut. Accessed 06 Jan 2022

Francke M, Korevaar M (2021) Housing markets in a pandemic: evidence from historical outbreaks. J Urban Econ 123:103333

Gilbert A (2015) Rental housing: the international experience. Habitat Int 54:173–181

Gökler LA (2022) Housing market dynamics: economic climate and its effect on Turkish housing. Housing in Turkey: policy, planning, practice. Routledge, London

Haaland C, Van Den Bosch CK (2015) Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: a review. Urban for Urban Green 14(4):760–771

Himmelberg C, Mayer C, Sinai T (2005) Assessing high house prices: Bubbles, fundamentals and misperceptions. J Econ Perspect 19(4):67–92

Huang N, Pang J, Yang Y (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the housing market in China. Soc Sci Electron Publ. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3642444

İçişleri Bakanlığı TC (2020a) Koronavirüs Salgını Yeni Tedbirler. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/koronavirus-salgini-yeni-tedbirler. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

İçişleri Bakanlığı TC (2020b) 81 İle Koronavirüs Salgını Yeni Tedbirler Genelgesi. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/81-ile-koronavirus-salgini-yeni-tedbirler-genelgesi. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

İçişleri Bakanlığı TC (2020c) Koronavirüs Ek Tedbirleri Genelgesi. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/koronavirus-ek-tedbirleri-genelgesi. Accessed 02 Jan 2022.

İçişleri Bakanlığı TC (2021a) 81 İl Valiliğine Kademeli Normalleşme Tedbirleri Genelgesi Gönderildi. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/81-il-valiligine-kademeli-normallesme-tedbirleri-genelgesi-gonderildi. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

İçişleri Bakanlığı TC (2021b) 81 İl Valiliğine Koronavirüs Tedbirlerinin Gözden Geçirilmesi Genelgesi Gönderildi. https://www.icisleri.gov.tr/81-il-valiligine-koronavirus-tedbirlerinin-gozden-gecirilmesi-genelgesi-gonderildi. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

Keleş R (2015) 100 soruda Türkiyeʼde kentleşme, konut ve gecekondu. Cem Yayınevi, İstanbul

Kholodilin KA (2020) Housing policies worldwide during coronavirus crisis: Challenges and solutions. DIW, Berlin

Kuk J, Schachter A, Faber JW, Besbris M (2021) The COVID-19 pandemic and the rental market: evidence from craigslist. Am Behav Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211003149

Leung KM, Yiu CY (2019) Rent determinants of sub-divided units in Hong Kong. J Housing Built Environ 34(1):133–151

Li T, Jing X, Wei O, Yinlong L, Jinxuan L, Yongfu L, Li W, Ying J, Weipan X, Yaotian M, Yifan D (2022) Mobility restrictions and their implications on the rental housing market during the COVID-19 pandemic in China’s large cities. Cities 126:103712

Liu S, Su Y (2021) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the demand for density: evidence from the US housing market. Econ Lett 207:110010

Malpezzi S (2003) Hedonic pricing models: a selective and applied review. In: O’Sullivan T, Gibb K (eds) Housing economics and public policy. Blackwell, Malden, pp 67–89

Nanda A, Thanos S, Valtonen E, Xu Y, Zandieh R (2021) Forced homeward: The COVID-19 implications for housing. Town Planning Review 92(1):25–31

Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, Agha R (2020) The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg 78:185–193

Palabıyık DÇ (2020) Bakan Albayrak'tan yeni finansman paketi değerlendirmesi. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/ekonomi/bakan-albayraktan-yeni-finansman-paketi-degerlendirmesi/1860679. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

Qian X, Qiu S, Zhang G (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on housing price: evidence from China. Financ Res Lett 43:101944

Resmî Gazete TC (2011) Turkish Law of Obligations (6098 sayılı Türk Borçlar Kanunu). 27836, 04 Şubat 2011

Resmî Gazete TC (2012) Law on Transformation of Areas at Disaster Risk (6306 Sayılı Afet Riski Altındaki Alanların Dönüştürülmesi Hakkında Kanun). 28309, 16 Mayıs 2012

Sahin T, Girgin Y (2021) Central Banks Cut Interest Rates 207 Times in 2020, AA Economy, 18 January 2021. Aa.com.tr/en/economy/central-banks-cut-interest-rates-207-times-in-2020/2113971. Accessed 08 Jan 2022

Sarıoglu GP (2007a) Hollanda’da Konut Politikaları ve İpotekli Kredi Sistemi. METU JFA, Ankara

Sarıoglu GP (2007b) Türkiye’de konut araştırmaları için veri kaynakları ve geliştirme olanakları üzerine. Planlama Dergisi 2:43–48

Sarıoglu Erdoğdu GP (2022) Limitations of housing research data in Turkey and proposals for a better system. Housing in Turkey: policy, planning, practice. Routledge, London

Scanlon K (2011) Private renting in other countries. In: Scanlon K, Kochan B (eds) Towards a sustainable private rented sector - the lessons from other countries. LSE London, London, pp 15–44

Scanlon K, Kochan B (2011) Towards a sustainable private rented sector: The lessons from other countries. London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE London

Scanlon K, Whitehead C (2011) Introduction: the need for a sustainable private rented sector. Towards a sustainable private rented sector: The lessons from other countries. London School of Economics and Political Science, LSE London

Sert Karaaslan Y (2020) A’dan Z’ye Kovid-19 rehberi. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/kategori-sayfasi-manset/adan-zye-kovid-19-rehberi/1777116. Accessed 02 Jan 2022

Tekeli İ (1996) Türkiye'de yaşamda ve yazında konut sorununun gelişimi. T.C. Başbakanlık Toplu Konut İdaresi Başkanlığı, Ankara

Tekeli İ (2010) Konut Sorununu Konut Sunum Biçimleriyle Düşünmek. Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, İstanbul

Tomal M, Helbich M (2022) The private rental housing market before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a submarket analysis in Cracow, Poland. Environ Plan B Urban Anal City Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083211062907

Tomal M, Marona B (2021) The impact of the covid-19 pandemic on the private rental housing market in poland: What do experts say and what do actual data show? Crit Hous Anal 8(1):24

Toprak D (2015) Uygulamada Ortaya Çıkan Farklı Refah Devleti Modelleri Üzerine Bir İnceleme. J Suleyman Demirel Univ Inst Soc Sci 21(1):151–175

Trojanek R, Gluszak M, Hebdzynski M, Tanas J (2021) The COVID-19 pandemic, Airbnb and housing market dynamics in Warsaw. Crit Hous Anal 8(1):72–84

TURKSTAT (2022) House sales by provinces and years, 2013-202.

Ugurlar A (2013) Türkiye’de Kiralık Konut: Ankara Örneğinde Talep ve Kullanım. Özellikleri (Doktora Tezi). Gazi Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, Ankara

Ugurlar A, Eceral TÖ (2014) Ankara’da mevcut konut (mülk ve kiralık) piyasasına ilişkin bir değerlendirme. İdealkent 5(12):132–159

Verbrugge R, Dorfman A, Johnson W, Marsh F III, Poole R, Shoemaker O (2017) Determinants of differential rent changes: mean reversion versus the usual suspects. Real Estate Econ 45(3):591–627

Waldron R (2022) Experiencing housing precarity in the private rental sector during the covid-19 pandemic: the case of Ireland. Hous Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2022.2032613

Wang B (2021) How does COVID-19 affect house prices? A cross-city analysis. J Risk Financ Manage 14(2):47

Whitehead CM, Monk S, Markkanen S, Scanlon K (2012) The private rented sector in the new century: a comparative approach (med dansk sammenfatning). Boligøkonomisk Videncenter, Copenhagen

World Health Organization (WHO) (2022a) WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/ Accessed 29 June 2022

World Health Organization (WHO) (2022b) Retrieved from https://covid19.who.int/region/euro/country/tr. Accessed 22 January 2022

Yiu CY (2021) Why House prices increase in the COVID-19 recession: a five-country empirical study on the real interest rate hypothesis. Urban Science 5(4):77

Zhai W, Peng ZR (2021) Where to buy a house in the United States amid COVID-19? Environ Plan Econ Space 53(1):9–11

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Subaşı, S.Ö., Baycan, T. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on private rental housing prices in Turkey. Asia-Pac J Reg Sci 6, 1177–1193 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-022-00262-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-022-00262-7