Abstract

This paper empirically investigates and theoretically reflects on the generality of some “stylized facts” of business cycles. Using data for 1960–2016 and a sample of OECD countries, the duration of business cycles as well as three models capturing core macroeconomic relations are estimated: the Phillips curve (the inflation-unemployment nexus), Okun’s law (i.e. the relation between output growth and unemployment) and the inflation-output relation. Results are validated by relevant statistical tests. Observed durations vary from 4.2 to 7.4 years, and estimated coefficients differ in signs and magnitudes. An explanation of this heterogeneity is attempted by referring to proxies for various institutional variables. The findings suggest that core coefficients in the relations, such as the slope of the Phillips curve, show significant correlation with some of these variables, but no uniform results are obtained. In the detailed theoretical discussion and interpretation it is thus argued that the notable differences between countries call the universality of the “stylized facts” into question, but also that these variations cannot be explained exhaustively by the institutional proxy variables employed here.

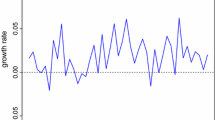

Source Own illustration, based on the HP filtered data of real GDP per capita, 1960–2016

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

First we test for heteroscedasticity and apply the robust errors only if the tests suggests heteroscedasticity on the 5% level. Robust errors do not alter the coefficients of interest; however, the significance level may change.

A 5% benchmark for the autocorrelation test is used and the autocorrelation consistent errors are applied only where necessary. As in the case of robust errors, the coefficients remain the same.

The VAR approach in context of business cycle theory is extensively discussed by Stock and Watson (2016).

The specifications contain from one to three lags according to parsimony and with consideration of the autocorrelation and normality tests for the residuals.

Setting signal dimensions higher than two does not significantly shift the estimated value of the dominant frequency and merely creates additional humps in the pseudo-spectrum up to the fourth signal dimension.

The estimates for the four models of interest are validated with tests for autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity.

Parametric methods are preferred if the data are normally distributed. Otherwise, one should consider non-parametric estimates. In this paper, normality is checked for with the test as in Shapiro and Wilk (1965). According to the test, the institutional proxies are not normally distributed and therefore non-parametric methods are appropriate.

The countries were selected according to the availability of especially the institutional data and bearing in mind the time frames.

For example, it is also worth noting in this context that the estimates of total business cycle duration used in the similar analysis of Altug et al. (2012, 350) are considerably longer at around 8 years on average. Despite the different sample and time period covered, this may be an instructive observation because the method Altug et al. (2012, 349 f.) used to determine the duration is different once again, namely based on an identification of peaks and troughs of fluctuations.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as fundamental cause of long-run growth. In P. Aghion & S. N. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 1A, pp. 385–472). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Agresti, A.-M., & Mojon, B. (2001). Some stylised facts on the euro area business cycle. ECB working paper series, 95.

Altug, S., & Canova, F. (2014). Do institutions and culture matter for business cycles? Open Economies Review, 25(1), 93–122.

Altug, S., Neyapti, B., & Emin, M. (2012). Institutions and business cycles. International Finance, 15(3), 347–366.

Andreano, M. S., & Savio, G. (2002). Further evidence on business cycle asymmetries in G7 countries. Applied Economics, 34(7), 895–904.

Arnone, M., Laurens, B. J., Segalotto, J.-F., & Sommer, M. (2007). Central bank autonomy: Lessons from global trends. IMF working papers 07/88, International Monetary Fund.

Bassani, A., & Duval R. (2006). Employment patterns in OECD countries: Reassessing the role of policies and institutions. OECD social, employment and migration working paper no. 35.

Baxter, M., & King, R. (1999). Measuring business cycles: Approximate band-pass filters for economic time series. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(4), 575–593.

Benczur, P., & Ratfai, A. (2014). Business cycles around the globe: Some key facts. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 50(2), 102–109.

Bergman, U. M., Bordo, M. D., & Jonung, L. (1998). Historical evidence on business cycles: The international experience. In J. C. Fuhrer & S. Schuh (Eds.), Beyond shocks: What causes business cycles?, volume 42 of conference series (pp. 65–113). Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Breusch, T. S. (1978). Testing for autocorrelation in dynamic linear models*. Australian Economic Papers, 17(31), 334–355.

Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1979). A simple test for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica, 47(5), 1287–94.

Burns, A. F., & Mitchell, W. C. (1946). Measuring business cycles. NBER book series studies in business cycles. New York: NBER.

Calmfors, L., Driffill, J., Honkapohja, S., & Giavazzi, F. (1988). Bargaining structure, corporatism and macroeconomic performance. Economic Policy, 3(6), 14–61.

Canova, F., Ciccarelli, M., & Ortega, E. (2012). Do institutional changes affect business cycles? Evidence from europe. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 36(10), 1520–1533.

Cukierman, A., Webb, S. B., & Neyapti, B. (1992). Measuring the independence of central banks and its effect on policy outcomes. The World Bank Economic Review, 6(3), 353–398.

Fiorito, R., & Kollintzas, T. (1994). Stylized facts of business cycles in the g7 from a real business cycles perspective. European Economic Review, 38(2), 235–269.

Fonseca, R., Patureau, L., & Sopraseuth, T. (2009). Divergence in labor market institutions and international business cycles. Annals of Economics and Statistics, (95/96):279–314.

Fonseca, R., Patureau, L., & Sopraseuth, T. (2010). Business cycle comovement and labor market institutions: An empirical investigation. Review of International Economics, 18(5), 865–881.

Glaeser, E. L., La Porta, R., Lopez-de Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (2004). Do institutions cause growth? Journal of Economic Growth, 9(3), 271–303.

Gnocchi, S., Lagerborg, A., & Pappa, E. (2015). Do labor market institutions matter for business cycles? Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 51, 299–317.

Godfrey, L. G. (1978). Testing against general autoregressive and moving average error models when the regressors include lagged dependent variables. Econometrica, 46(6), 1293–1301.

Haberler, G. (1946). Prosperity and depression. A theoretical analysis of cyclical movements (3rd ed.). New York: United Nations.

Hodrick, R. J., & Prescott, E. C. (1997). Postwar U.S. business cycles: An empirical investigation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(1), 1–16.

Huang, H.-C. R., & Yeh, C.-C. (2013). Okuns law in panels of countries and states. Applied Economics, 45(2), 191–199.

Johansen, S. (1995). Likelihood-based inference in cointegrated vector autoregressive models. Number 9780198774501 in OUP catalogue. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaldor, N. (1957). A model of economic growth. The Economic Journal, 67(268), 591–624.

Kendall, M. G. (1938). A new measure of rank correlation. Biometrika, 30(1/2), 81–93.

Kollintzas, T., Konstantakopoulou, I., & Tsionas, E. (2011). Stylized facts of money and credit over the business cycles. Applied Financial Economics, 21(23), 1735–1755.

Kromphardt, J. (1993). Wachstum und Konjunktur. Grundlagen der Erklärung und Steuerung des Wachstumsprozesses, volume 26 of Grundriss der Sozialwissenschaft (3rd ed.). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Kydland, F. E., & Prescott, E. C. (1990). Business cycles: Real facts and a monetary myth. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review, 14(Spring), 3–18.

Lucas, R. E. (1977). Understanding business cycles. In K. Brunner & A. Meltzer (Eds.), Stabilization of the domestic and international economy (pp. 7–29). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Maußner, A. (1994). Konjunkturtheorie. Berlin: Springer.

Milanovic, B. (2014). All the Ginis database [ATG]. Accessed on August 30, 2017.

Mitchell, W. C. (1951). What happens during business cycles: A progress report. NBER book series studies in business cycles. New York: NBER.

Moosa, I. A. (1997). A cross-country comparison of Okun’s coefficient. Journal of Comparative Economics, 24(3), 335–356.

Newey, W. K., & West, K. D. (1987). A simple, positive semi-definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica, 55(3), 703–08.

Nickell, W. (2006). The CEP-OECD institutions data set (1960–2004). CEP discussion paper no. 759.

North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.

Ochel, W. (2001). Collective bargaining coverage in the OECD from the 1960s to the 1990s. CESifo Forum, 2(4), 62–65.

Okun, A. M. (1962). Potential GNP: Its measurement and significance. In American Statistical Association (ed.), Proceedings of the business and economic statistics section.

Perman, R., & Tavera, C. (2005). A cross-country analysis of the Okun’s law coefficient convergence in Europe. Applied Economics, 37(21), 2501–2513.

Pisarenko, V. F. (1973). The retrieval of harmonics from a covariance function. Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 33(3), 347–366.

Ravn, M. O., & Uhlig, H. (2002). On adjusting the Hodrick–Prescott filter for the frequency of observations. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(2), 371–375.

Rodrik, D. (2000). Institutions for high-quality growth: What they are and how to acquire them. Studies in Comparative International Development, 35(3), 3–31.

Romer, C. D. (2008). Business cycles. In D. R. Henderson (Ed.), The concise encyclopedia of economics (2nd ed.). Indianopolis: Library of Economics and Liberty.

Rumler, F. & Scharler, J. (2009). Labor market institutions and macroeconomic volatility in a panel of OECD countries. ECB working paper series, 1005.

Ryan, C. (2002). Business cycles: Stylized facts. In B. Snowdon & H. R. Vane (Eds.), An encyclopedia of macroeconomics (pp. 97–104). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Schmidt, R. O. (1986). Multiple emitter location and signal parameter estimation. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, 34, 276–280.

Shapiro, S. S., & Wilk, M. B. (1965). An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52(3/4), 591–611.

Spearman, C. (1987). The proof and measurement of association between two things. By C. Spearman, 1904. The American Journal of Psychology, 100(3–4), 441–471.

Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2016). Dynamic factor models, factor-augmented vector autoregressions, and structural vector autoregressions in macroeconomics. In J. B. Taylor & H. Uhlig (Eds.), Handbook of macroeconomics (Vol. 2, pp. 415–525). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

The Conference Board. (2017). Total economy database. Accessed on August 30, 2017.

The World Bank. (2017). World development indicators, trade (% of GDP) [NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS]. Accessed on September 25, 2017.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48(4), 817–38.

Woitek, U. (1997). Business cycles. An international comparison of stylized facts in a historical perspective. Heidelberg: Physica.

Zarnowitz, V. (1992). Business cycles: Theory, history, indicators, and forecasting. NBER book series studies in business cycle. Chicagos: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Harald Hagemann, Martyna Marczak, Klaus Prettner and Johannes Schwarzer for their support during the work on the given paper and beyond. In addition, the authors are thankful to Michael Graff and the anonymous referees for their suggestions and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kufenko, V., Geiger, N. Stylized Facts of the Business Cycle: Universal Phenomenon, or Institutionally Determined?. J Bus Cycle Res 13, 165–187 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-017-0018-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-017-0018-5