Abstract

Barriers to mental health care, including stigma, costs, and mental health professional shortages, have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Smartphone apps have the potential to increase scalability and improve access to mental health information, support, and interventions. However, evaluating these apps and selecting ones for use in care remain challenging, especially as apps are often updating and changing. Recommending apps requires knowledge of how stable apps are as the experience of one user several months ago may or may not be the same. A sample of 347 apps of the 650 apps on the M-health Index and Navigation Database (MIND) https://mindapps.org were reviewed between September 1, 2021, and January 5, 2022. Apps were selected by time since their last review, with updates occurring on average approximately 4 months from the last review. Eleven trained app evaluators reviewed apps across 105 evaluation criteria in 9 categories. Results were compared to initial ratings, identifying the changes that occurred. The average app updates every 433 days, though 19% were updated in the last 3 months and some nearly weekly. Changes in privacy and features made up the highest percentage of changes, both at 38%. The most frequently observed privacy-related change was increased privacy policy reading level. Functionality parameters changed in 28% of apps. The most common functionality change was the removal of an accessibility feature. Clinical foundations changed in 18% of apps and 9% added supporting studies. Cost structure changed in 17% of apps, with 10% adding a fee for use of the app. Engagement features changed in 17% of the apps, with additions and removals of validated assessments or screeners most common. The dynamic nature of the app stores is reflected in app privacy, features, and functionality. These changes, reflected by the increased reading levels required to understand privacy policies, the decrease in accessibility features, and the additions of fees to access mobile apps, reflect the need to constantly review apps and understand how they are evolving. Patient and clinicians should use the most recent and updated possible when evaluating apps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 1 in 5 US adults experienced mental illness in 2020, yet only 46% received treatment (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2021). Barriers to treatment include stigma, privacy concerns, costs, time constraints, and mental health professional shortages (Lattie et al., 2022; Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic introduced new barriers and exacerbated existing ones. While the demand for mental health services has increased, accessibility to face-to-face care has decreased (National Center for Health Statistics, 2020; Ganson et al., 2020; Pierce et al., 2021; Purtle, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). Underserved and high-risk populations continue to be disproportionately affected (National Center for Health Statistics, 2020; Kirby, 2020; Nagata et al., 2021). The growing demand for services has increased the need for unique solutions.

Mobile technology and smartphone apps offer one such solution with the potential to increase the capacity and improve access to mental health information, support, and interventions through scalable smartphones (Figueroa & Agilera, 2020). In 2020, 85% of Americans owned a smartphone, and access was high across all demographics, including minority and disadvantaged populations (Pew Research Center, 2021). This high prevalence of smartphone ownership suggests that mobile health interventions have the potential to improve access and reach traditionally underserved populations. Interest in mobile health solutions has grown since their introduction over 10 years ago, and the COVID-19 pandemic amplified interest to new high levels for all stakeholders, including patients, providers, and health insurance payers (Inkster & Digital Mental Health Data Insights Group, 2021).

Given the pressing need for more mental health services, research and commercial offerings have rapidly expanded. The literature indicates that apps are highly acceptable to patients, even those with serious mental illness (Torous et al., 2018), and feasibility is no longer a question. Results are more mixed for efficacy, with the most robust data suggesting a small but positive effect that is often less than that marketed (Goldberg et al., 2022). However, even the most comprehensive literature reviews do not identify which apps may be most effective for any particular patient or how to make an informed choice regarding selection.

The challenge is pressing, with even pre-COVID data suggesting that over 30% of youth may already be turning to mental health apps as first-line tools when they have a mental health concern (Cohen et al., 2021). While more than 10,000 mental health focused apps are available, few are empirically supported. An analysis of 278 mental health apps revealed that only 16% were supported by a feasibility or efficacy study (Lagan et al., 2021a). In addition, translation and implementation from clinical to real-world settings have been a challenge (Lattie et al., 2022; Lipschitz et al., 2019; Torous et al., 2018). Moreover, the fact that apps are dynamic and constantly updated makes evaluating them even more challenging for clinicians and patients. A 2016 paper examined the dynamics of mental health apps and reported that every 2.9 days a depression app disappears from the app stores (Larsen et al., 2016). However, this paper only explored the rate of apps being removed from the marketplace and not the nature of changes within apps over time.

In addition to the clear clinical decision-making benefits of understanding apps changes over time, this knowledge is also relevant to regulatory efforts. The FDA’s next generation of regulation of software as a medical device is called the Pre-Certification program. A critical component of the program is to use real-world data to evaluate when an app needs to be re-examined or re-approved (Kadakia et al., 2020). Data on how apps change over time is thus necessary to inform programs like Pre-Certification.

The majority of apps that fall outside of this regulation instead self-identified as wellness devices (Kahane et al., 2021). This information is still critical for patients and clinicians seeking to evaluate the stability of wellness apps. Given that most wellness apps are not bound to protect personal health data and can legally transfer or sell it to third parties (Blenner et al., 2016), the need for timely information about risks of these apps is important. Recognition of this need has led professional organizations like the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to offer public facing guidance and education around evaluation of apps (Lagan et al., 2021b).

The APA’s App Evaluation Model was developed as a way to critically evaluate an app by answering questions regarding background information, privacy and security, clinical foundation, ease of use, and interoperability. It was developed through a six-step process distilling 961 questions across 45 app evaluation frameworks into 357 questions across five categories, then updated for clarity in concert with the APA’s Expert App Evaluation Panel (Henson et al., 2019). The model’s interrater reliability is detailed in previous literature (Lagan et al., 2020). The APA App Evaluation Model was operationalized into 105 objective binary or numeric questions, which serve as the foundation of the M-health Index and Navigation Database (MIND) (see Appendix) (Lagan et al, 2020).

The M-health Index and Navigation Database (MIND), accessible at https://mindapps.org, is an easily accessible and free database of over 650 mental health apps, each rated across 105 questions with a focus on accessibility, privacy, evidence, engagement, and therapeutic goal. MIND has been noted as one of the most comprehensive databases that reflects diversity, equity, and inclusion principles (Ramos et al., 2021), adopted by third parties (Spadaro et al., 2022), and reaches beyond academics into the popular press (The Economist, 2021; Esquire, 2021; Maldarelli & Whitcomb, 2022). Users are able to filter by criteria and find apps that meet their individual needs and access app information across nine categories. Apps on MIND are regularly updated within 100–180 days to ensure current information and provide insights over time. Thus, the detailed data on and frequent updating of apps on mindapps.org presents an ideal platform to study the dynamic of apps and how they change over time. This paper analyzes apps available on MIND to investigate prominent changes in efficacy, safety, and privacy over time.

Methods

A sample of 347 apps of the 650 apps available on MIND were reviewed between September 1, 2021, and January 5, 2022. Apps were selected by time since their last review with the oldest apps rated first. All apps were updated within 6 months of last review, with updates occurring on average approximately 4 months from the last review. Apps were downloaded from the Apple iOS store and Google Play store and reviewed by eleven trained app evaluators by updating answers to 105 questions in 9 categories, according to the American Psychiatric Association App Evaluation Model (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). All raters underwent interrater reliability training. Training included instruction on the APA App Evaluation Model, reviewing each of the 105 questions and potential responses with the project manager, practicing app evaluations and reviewing potential errors, and passing an assessment of interrater reliability. Interrater reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa statistic (Lagan et al., 2020), for which raters demonstrated very good interrater reliability, defined as a kappa value above 0.750. App evaluations were reviewed by the project manager and raters met with the project manager weekly to review questions. After app evaluation of 347 apps, data was tabulated and change parameters were measured by percentage of apps changed across the following 9 categories: privacy, features, functionalities, cost, clinical foundations, engagements, supported conditions, uses, and developer type. See Appendix for a complete list of evaluation criteria.

Results

The average app updates every 433 days, though 19% (n = 65) were updated in the last 3 months and some nearly weekly. In the 3-month period between September 1, 2021, and January 5, 2022, 6% (n = 21) of apps were removed from platforms. The percentage of apps with changes was high across the nine app rating categories. Application changes were at least 10% in 8 of 9 categories, 27% in 3 of 9 categories, and 38% in 2 of 9 categories. Only the category of developer type showed little change, which is to be expected. Details are shown below in Table 1.

Privacy and Security

Privacy and security factors changed in 38% (n = 133) of apps. The most frequently observed privacy-related change was increased privacy policy reading level. The next most common change was the addition of the ability to delete your own data.

Features

Features also changed in 38% (n = 133) of apps. The four most common changes to app features were as follows: the addition of physical exercise, addition of goal setting related content, removal of productivity, and removal of psychoeducation content.

Functionality

Functionality parameters changed in 28% (n = 88) of apps. The most common change was the removal of an accessibility feature. The subsequent most common changes were additions to exportability and offline access. Functionality features were removed (53%) more often than they were added (47%).

Clinical Foundation

Clinical foundations changed in 18% (n = 58) of the apps, with the most common changes being improvements or additions (84%). The most common changes indicate that apps have improved the writing and correctness of content and added disclaimers that they are not a replacement for care. In addition, 9% (n = 29) of apps added supporting studies.

Engagement Style, Cost Structure, and Supported Conditions

Engagement features changed in 17% (n = 54) of the apps, and of those changes 52% were additions and 48% were removals. The majority of the changes were additions and removals of clinically validated assessments or screeners. Cost structure changed in 17% (n = 56) of apps, with 10% adding a fee for use of the app. Supported conditions changed in 12% (n = 40) of apps. Mood disorders and sleep were the most common conditions added, while stress and anxiety conditions were the most commonly removed.

Comparison of Paid and Unpaid Apps

Although 35% (n = 114) of apps were totally free and 66% (n = 216) were free to download, 41% (n = 143) offered in-app purchases, 35% (n = 114) offered subscriptions, and 20% (n = 70) had a one-time payment. Of free to download apps, 88% (n = 190) also offered in-app purchases, subscriptions, or one-time payment. Paid apps (apps that were not totally free or free to download) changed more than unpaid apps in privacy, cost, and clinical foundations. Unpaid apps changed more than paid apps in features, functionalities, engagements, supported conditions, and uses as shown in Tables 2 and 3. There were technical issues in 20% of unpaid apps, but only 3% of paid apps.

Comparison of Developer Types

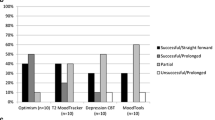

Eighty-eight percent (n = 304) of apps reviewed in this paper from MIND were from for-profit developers. Academic institutions developed 3% (n = 10) of apps, government 4% (n = 14), nonprofit companies 3% (n = 10), and healthcare providers 3% (n = 9). Partnerships between two or more developer types were responsible for 4% (n = 14) of apps. The app rating categories with the highest changes (see Fig. 1) were not uniform across app developer types, but privacy was consistently high across developer types. Thirty-three percent (n = 3) of apps from healthcare developers made privacy and clinical foundations changes; 21% (n = 3) of apps from government developers made privacy, features, functionality, clinical foundations, and engagement changes; 50% (n = 5) of apps from non-profit developers made changes to privacy; and 70% (n = 7) of apps from academic developers made changes in clinical foundations.

Discussion

Our results confirm the dynamic nature of mental health apps and highlight frequent changes in their privacy protections, functionality, and features. While how these changes may benefit or harm the user is not simple to discern, we can say that the frequent and varied nature of these changes necessitates evaluation based on constantly updated data.

Dynamic pricing models combined with transparency in data reporting from apps will be necessary to understand the economic value of mental health apps. For health insurance payers to offer app formularies, they need to create metrics to assess these changes in the app landscape or tightly control app updates themselves. Other aspects necessary for valuation, such as real-world engagement with the apps and mean effect size, are not publicly available and thus not reported in our results.

One practical consideration of our results is to caution patients and clinicians away from static app rating systems that rely on outdated information. While having lists of “the best” or “top 10” apps is appealing, the challenge in trusting data from these sources is highlighted with our results showing that after just 4 months over a quarter of apps made changes to privacy, features, or functionality. While many app rating websites or services do not always note when they last updated content, a 2019 paper offers information with Mindtool.io having a mean of 714 days, Psyberguide 598 days, and ORCHA 109 days (Carlo et al., 2019). Our team’s prior findings that apps not updated in 180 days may be a marker for lower quality apps (Liu et al., 2019) offer further caution towards relying on out-of-date apps in addition to reviews of apps that are also out of date.

Our findings also suggest that mental health apps are becoming more difficult for the average user to navigate. This is depicted by the increased reading levels required to understand privacy policies, the decrease in accessibility features, and the additions of fees to access mobile apps. The most common changes to privacy, functionality, and cost have profound implications, especially for vulnerable or high-risk populations. Privacy risk is high—a great percentage of the apps reviewed made changes to privacy features, yet users are unlikely to review privacy feature changes regularly. Those who regularly review privacy features will find information on data sharing challenging to parse, with missing or complicated explanations around sharing protected health information, de-identified data, anonymized data, and sharing policies with third parties. One solution to the increasing complexity of app evaluation is to offer support in the form of a trained staff member, called a digital navigator (Wisniewski et al., 2020), who can guide users through the many choices. Researchers examining app evaluation have noted that the process can feel like a “minefield” (Szinay et al., 2021), called for assistance from digital navigators (Roberts et al., 2021), and offered detailed training resources (Wisniewski et al., 2020).

Results of our study are in line with prior work. Larsen et al. in 2016 found that 50% of marketplace apps were no longer found using the same search terms after 130 days but did not examine how many apps were actually removed from the marketplace. We found nearly 40% change in apps across a similar time frame although did not confirm if these changes resulted in different search results. When updating the 177 apps reviewed on Pysberguide, the authors report that 9% of those apps they publicly reviewed were no longer available (Neary et al., 2021), which is similar to our result of 6%.

This study is limited to apps in MIND and the sample may not be representative as app update order was not randomized. Important metrics such as average length of user engagement (Molloy & Anderson, 2021) and average effect size of an app are not publicly available and thus we are not able to code them on MIND or report on them around app dynamics.

Conclusion

This study highlights the dynamic nature of the app store environments, revealing rapid and substantial changes that could present challenges for app selection, consumer safety, and assessing the economic value of apps. Future studies could evaluate the dynamics of particular subsets of apps in MIND, focusing on app types or conditions. Follow-up studies could investigate the reasons for app changes, for example, reasons privacy policy language reading levels are increasing or reasons for removal of apps from the marketplaces. There may also be changes in the app landscape dynamics pre- and post-pandemic due to COVID-19’s impact on mental health apps. With time, researchers using mindapps.org will be able to gather data over longer and longer periods, potentially allowing for modeling changes in the app landscape.

Data Availability

Updated data is avalaible on mindapps.org.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). The app evaluation model. Retrieved February 25, 2022, from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/mental-health-apps/app-evaluation-model

Blenner, S. R., Köllmer, M., Rouse, A. J., Daneshvar, N., Williams, C., & Andrews, L. B. (2016). Privacy policies of Android diabetes apps and sharing of health information. JAMA, 315(10), 1051–1052. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.19426

Carlo, A. D., Hosseini Ghomi, R., Renn, B. N., & Areán, P. A. (2019). By the numbers: Ratings and utilization of behavioral health mobile applications. NPJ Digital Medicine, 2, 54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0129-6

Cohen, K. A., Stiles-Shields, C., Winquist, N., & Lattie, E. G. (2021). Traditional and nontraditional mental healthcare services: Usage and preferences among adolescents and younger adults. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 20, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-020-09746-w

Dramatic growth in mental-health apps has created a risky industry. (2021, December 11). The economist. https://www.economist.com/business/2021/12/11/dramatic-growth-in-mental-health-apps-has-created-a-risky-industry

Figueroa, C. A., & Aguilera, A. (2020). The need for a mental health technology revolution in the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 523. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00523

Ganson, K. T., Weiser, S. D., Tsai, A. C., et al. (2020). Associations between anxiety and depression symptoms and medical care avoidance during COVID-19. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35, 3406–34082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06156-8

Goldberg, S. B., Lam, S. U., Simonsson, O., Torous, J., & Sun, S. (2022). Mobile phone-based interventions for mental health: A systematic meta-review of 14 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. PLOS Digital Health, 1(1), e0000002. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000002

Henson, P., David, G., Albright, K., & Torous, J. (2019). Deriving a practical framework for the evaluation of health apps. The Lancet Digital Health, 1(2), e52–e54.

Inkster, B., & Digital Mental Health Data Insights Group (DMHDIG). (2021). Early warning signs of a mental health tsunami: a coordinated response to gather initial data insights from multiple digital services providers. Frontiers in digital health, 2, 578902. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2020.578902

Kadakia, K., Patel, B., & Shah, A. (2020). Advancing digital health: FDA innovation during COVID-19. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-00371-7

Kahane, K., François, J., & Torous, J. (2021). Perspective: The digital health app policy landscape: Regulatory gaps and choices through the lens of mental health. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 24(3), 101–108. PMID: 34554108.

Kirby, T. (2020). Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(6), 547–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30228-9

Lagan, S., Aquino, P., Emerson, M. R., Fortuna, K., Walker, R., & Torous, J. (2020). Actionable health app evaluation: Translating expert frameworks into objective metrics. npj Digital Medicine, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-00312-4

Lagan, S., D’Mello, R., Vaidyam, A., Bilden, R., & Torous, J. (2021a). Assessing mental health apps marketplaces with objective metrics from 29,190 data points from 278 apps. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 144(2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13306

Lagan, S., Emerson, M. R., King, D., Matwin, S., Chan, S. R., Proctor, S., Tartaglia, J., Fortuna, K. L., Aquino, P., Walker, R., Dirst, M., Benson, N., Myrick, K. J., Tatro, N., Gratzer, D., & Torous, J. (2021b). Mental health app evaluation: Updating the American Psychiatric Association’s Framework Through a Stakeholder-Engaged Workshop. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.), 72(9), 1095–1098. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000663

Larsen, M. E., Nicholas, J., & Christensen, H. (2016). Quantifying app store dynamics: Longitudinal tracking of mental health apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(3), e96. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.6020

Lattie, E. G., Stiles-Shields, C., & Graham, A. K. (2022). An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nature Reviews Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-021-00003-1

Lipschitz, J., Hogan, T. P., Bauer, M. S., & Mohr, D. C. (2019). Closing the research-to-practice gap in digital psychiatry. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 80(3). https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.18com12659

Liu, G., Henson, P., Keshavan, M., Pekka-Onnela, J., & Torous, J. (2019). Assessing the potential of longitudinal smartphone based cognitive assessment in schizophrenia: A naturalistic pilot study. Schizophrenia research. Cognition, 17, 100144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2019.100144

Maldarelli, C., & Whitcomb, I. (2022). Mental wellness apps are basically the Wild West of therapy. Popular Science. Retrieved February 1, 2022, from https://www.popsci.com/science/mental-health-apps-safety/

Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). (2021). Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved February 1, 2022, from https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

Molloy, A., & Anderson, P. L. (2021). Engagement with mobile health interventions for depression: A systematic review. Internet interventions, 26, 100454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100454

Nagata, J. M., Ganson, K. T., Bonin, S. L., Twadell, K. L., Garcia, M. E., Langrock, O., Vittinghoff, E., Tsai, A. C., Weiser, S. D., & Abdel Magid, H. S. (2021). Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of unmet need for mental health counseling among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatric Services, appi.ps.2021001. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100111

National Center for Health Statistics. (2020). Mental health: Household pulse survey. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 27, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm

Neary, M., Bunyi, J., Palomares, K., Mohr, D. C., Powell, A., Ruzek, J., Williams, L. M., Wykes, T., & Schueller, S. M. (2021). A process for reviewing mental health apps: Using the One Mind PsyberGuide Credibility Rating System. DIGITAL HEALTH, 7, 205520762110536. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076211053690

Pew Research Center. (2021). Mobile fact sheet. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. Retrieved January 1, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile

Pierce, B. S., Perrin, P. B., Tyler, C. M., et al. (2021). The COVID-19 telepsychology revolution: A national study of pandemic-based changes in US mental health care delivery. American Psychologist, 2021(76), 14–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000722

Purtle, J. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health equity in the United States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 2020(55), 969–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01896-8

Ramos, G., Ponting, C., Labao, J. P., & Sobowale, K. (2021). Considerations of diversity, equity, and inclusion in mental health apps: A scoping review of evaluation frameworks. Behaviour research and therapy, 147, 103990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103990

Roberts, A. E., Davenport, T. A., Wong, T., Moon, H. - W., Hickie, I. B., & Lamonica, H. M. (2021). Evaluating the quality and safety of health-related apps and e-tools: Adapting the Mobile App Rating Scale and developing a quality assurance protocol. Internet Interventions, 24, 100379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100379

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21–07–01–003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved December 27, 2021, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data

Spadaro, B., Martin-Key, N. A., Funnell, E., & Bahn, S. (2022). mHealth solutions for perinatal mental health: Scoping review and appraisal following the mHealth index and navigation database framework. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 10(1), e30724. https://doi.org/10.2196/30724

Szinay, D., Perski, O., Jones, A., Chadborn, T., Brown, J., & Naughton, F. (2021). Influences on the uptake of health and well-being apps and curated app portals: Think-aloud and interview study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(4), e27173. https://doi.org/10.2196/27173

The reluctant man’s guide to starting therapy. (2021, December 30). Esquire. https://www.esquire.com/lifestyle/a38241141/guide-to-starting-therapy-mental-health/

Torous, J., Wisniewski, H., Liu, G., & Keshavan, M. (2018). Mental health mobile phone app usage, concerns, and benefits among psychiatric outpatients: Comparative survey study. JMIR Mental Health, 5(4), e11715. https://doi.org/10.2196/11715

Wisniewski, H., Gorrindo, T., Rauseo-Ricupero, N., Hilty, D., & Torous, J. (2020). The role of digital navigators in promoting clinical care and technology integration into practice. Digital Biomarkers, 4(Suppl 1), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510144

World Health Organization. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on mental, neurological and substance use services: Results of a rapid assessment. Retrieved December 27, 2021 from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/335838/9789240012455-eng.pdf

Funding

Argosy Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception/model: JT, EC. Data collection: SES, ETH, EC. Analysis/interpretation: SES, EC, JT. Writing: SES, EC, ETH, JT. Editing: SES, EC, ETH, JT.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

JT has received past research support from Otsuka. JT is the co-founder of a mental health company called Precision Mental Wellness. SES is an employee of Happify Health and consultant for Found Health. These apps were not rated on MINDapps by SES to ensure impartiality.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix. MindApps Database: complete list of evaluation categories and criteria

Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

Platform | Android |

iOs | |

Web | |

Cost | Free to download |

Totally free | |

One-time payment | |

In-app purchase(s) | |

Subscription | |

Developer types | Government |

For profit company | |

Non-profit company | |

Healthcare company | |

Academic institution | |

Supported conditions | Mood disorders |

Stress & anxiety | |

Sleep | |

Phobias | |

OCD | |

Schizophrenia | |

Eating disorders | |

Personality disorders | |

Self-harm | |

PTSD | |

Substance use | |

Substance use (alcohol) | |

Substance use (smoking & tobacco) | |

Headache | |

Pain | |

Non-specific | |

Functionalities | Spanish |

Offline | |

Accessibility | |

Own your own data | |

Email or export your data | |

Send your data to a medical record | |

Uses | Self help |

Reference | |

Hybrid | |

Features | Track mood |

Track medication | |

Track sleep | |

Track symptoms | |

Productivity | |

Physical health | |

Psychoeducation | |

Journaling | |

Mindfulness | |

Deep breathing | |

Picture gallery/hope board | |

iCBT or sleep therapy | |

CBT | |

ACT | |

DBT | |

Peer support | |

Coach/therapist connection | |

Biodata | |

Goal setting/habits | |

Physical health exercises | |

Chatbot interaction | |

Bio feedback with sense data | |

Engagements | User generated data |

Chat/message | |

Assessments/screenings | |

Real time response | |

Asynchronous response | |

Gamification (points/badges) | |

Videos | |

Audio/music/scripts | |

AI support | |

Peer support | |

Network support | |

Collaborative with provider/other | |

Application inputs | Surveys |

Diary | |

Geolocation | |

Camera | |

Microphone | |

Step count | |

External devices | |

Social network | |

Application outputs | Notifications |

References/information | |

Social network | |

Reminders | |

Graphs of data | |

Summary of data | |

Link to formal care/coaching | |

Evidence & clinical foundations | Well-written relevant content |

Does what it claims | |

Patient facing | |

Can cause harm | |

Use warning | |

Supporting studies | |

Privacy & security | Has privacy policy |

Data stored on device | |

Data stored on server | |

Can delete data | |

App declares data use and purpose | |

App reports security measures in place | |

Is PHI shared | |

Is de-identified data shared | |

Is anonymized/aggregate data shared | |

Can opt out of data collection | |

Claims to meet HIPAA | |

Has crisis management feature | |

Reading grade level of privacy policy |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Stoeckl, S.E., Torres-Hernandez, E., Camacho, E. et al. Assessing the Dynamics of the Mental Health Apple and Android App Marketplaces. J. technol. behav. sci. 8, 465–472 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-023-00300-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-023-00300-x