Abstract

Loneliness has emerged as a chronic and persistent problem for a considerable fraction of the general population in the developed world. Concurrently, use of online social media by the same societies has steadily increased over the past two decades. The present study analyzed a recent large country-wide loneliness survey of 20,096 adults in the US using an unsupervised approach for systematic identification of clusters of respondents in terms of their social media use and representation among different socioeconomic subgroups. We studied the underlying population heterogeneity with a computational pipeline that was developed to gain insights into cluster- or group-specific patterns of loneliness. In particular, distributions of high loneliness were observed in groups of female users of Facebook and YouTube of certain age, race, marital, and socioeconomic status. For instance, among the group of predominantly YouTube users, we noted that non-Hispanic white female respondents of age 25–44 years who have high school or less education level and are single or never married have more significant high loneliness distribution. In fact, their high loneliness scores also seem to be associated with self-reported poorer physical and mental health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to adoption of social distancing measures that have made societies worldwide acutely aware of phenomena such as loneliness and social isolation as well as rising concerns about their potential impacts on individual health and behavior. Yet, more general erosion of social ties and bonds within communities in the United States (US) and other parts of the developed world has long been observed. Some experts have positioned US to be in the midst of a deepening “loneliness epidemic (The “Loneliness Epidemic”, 2019).” While social isolation typically refers to the objective lack of (or limited) social contact of an individual with others, loneliness refers to the perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling that “one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or quality of one’s social relationships” (Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, 2020; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Peplau & Perlman, 1982).”

Loneliness is a chronic and persistent problem for about 15–30% of the general US population (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). About 80% of those under 18 years of age and 40% of adults over 65 years report being lonely at least sometimes (Berguno et al., 2004; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001; Weeks, 1994). A recent report notes that more than one-third of US adults aged 45 and older feel lonely, and nearly a quarter of adults aged 65 and older are considered to be socially isolated (Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, 2020). Different models to explain loneliness ranging from the individualistic nature of certain societies to cognitive maladaptation of individuals have been proposed (Lykes & Kemmelmeier, 2014; Masi et al., 2011).

In general, levels of loneliness reduce in middle age, and then increase at older ages. When left unattended, loneliness is known to have serious consequences for cognition, emotion, behavior, and physical health. Loneliness and social isolation are comparable to other risk factors such as smoking, lack of exercise, obesity, and high blood pressure in older adults (Fakoya et al., 2020). Further, loneliness is associated with cognitive decline, depression, dementia, reduced immunity, and suicidal ideation (Calati et al., 2019; Jaremka et al., 2013; Sutin et al., 2020). Both social isolation and loneliness were found to be associated with increased all-cause mortality, and conversely, social integration with reduced mortality risk (Hobbs et al., 2016; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Steptoe et al., 2013).

It seems ironic that concurrent to this growing loneliness phenomenon in the developed world, the past two decades have also seen tremendous increase in the use of Internet-based social media platforms by the same societies. Here, we refer to social media as a broad term encompassing all communication platforms and technologies enabling users to create and share content with their constructed networks consisting of friends, followers, groups, etc. In principle, such platforms have the potential to address the problem of perceived social isolation through access to virtual supportive networks, including for those who may find it difficult to engage in face-to-face interactions. Yet, curiously, aggressive social media use may increase perceived social isolation because users may choose to use social media interactions in lieu of in-person interactions thereby leading to weakening of ties within groups and lowering of social capital (Rasmussen & Rasmussen, 2014; Steinfield et al., 2008).

There is little doubt that social media has revolutionized how human beings interact with each other in the 21st century. Social media use among the US adults has steadily increased since the early 2000s (The rise of social media - Our World in Data, 2020). During just the first quarter of 2019, there were 68 million Twitter users. In 2019, there were 180 million Facebook, 107.2 million Instagram, and 80.2 million users of Snapchat in the US. Other platforms such as YouTube, LinkedIn, Tumblr, Pinterest, etc., also continue to rise in their popularity and use (Social media - Statistics & Facts, 2020).

Interestingly, studies have shown that associations that may exist between rising social media use and increasing loneliness are not straightforward. Whereas some studies have noted a negative link between the two, others have not. Further, subtle platform-specific patterns were observed. For instance, while Instagram interaction and browsing were related to lower loneliness, broadcasting on the same platform was associated with higher loneliness (Yang, 2016). It was found that image-based social media was associated with increased perceived well-being and decreased loneliness whereas text-based social media use was not associated with psychological well-being (Pittman & Reich, 2016). Self-reported Facebook and Instagram use were found to correlate positively with depression, and higher Facebook use was associated with lower self-esteem and greater loneliness (Hunt et al., 2018; Quan-Haase & Young, 2010).

Researchers are now looking into different modes of spread—or “contagion”—of loneliness via social networks. To determine the role of various social network processes and to explore the topography of loneliness as it spread in such networks, they have used population-based data such as the Framingham Heart Study (Cacioppo et al., 2009). They noted that loneliness occurred in clusters, extended up to three degrees of separation, and spread though emotional contagion. Such transmission of loneliness was found to be stronger than the spread of perceived social connections, stronger for friends than family members, and stronger for women than for men. In fact, a meta-analysis of more than a hundred loneliness studies found that women report significantly higher levels of loneliness than men (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001). This appears to underscore the importance of studying group-specific, heterogeneous distributions of loneliness in a given population.

In this study, therefore, we adopted an unsupervised data-driven approach rather than making any model-based assumption about the association between social media use and loneliness. In such unsupervised learning of patterns, no class label is used to guide the grouping of the data, which is determined purely based on similarity among the samples. First, we identified the common patterns of social media use by clustering the respondents of a nationwide loneliness survey of US adults. Second, we used statistical testing for demographic characterization of these clusters. Third, we used a user-friendly procedure to select different socioeconomic subgroups of interest within the clusters, and observe and compare their distributions of loneliness and health outcomes. We perform these steps using a computational pipeline that was developed for integrating different types of data: social media use, demographic and socioeconomic variables, loneliness measures, and health outcomes.

The rich collection of variables used in our platform was originally recorded in the hitherto largest nationwide survey of loneliness among the US adults conducted by Cigna, a large US health services company, in 2018 (Bruce et al., 2019). Their report included a multivariable linear regression model which identified key contributors such as social anxiety and social media overuse to the outcome of loneliness (Bruce et al., 2019). The present study analyzed the survey data with a different unsupervised approach, which is described in the next section. The following section demonstrates the findings of that approach. We conclude with discussion and plans of future work.

Data and Methods

In this study, we analyzed survey data that were originally collected by Ipsos on behalf of Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company and Cigna Behavioral Health, Inc., and provided to us courtesy of Cigna. (Bruce et al., 2019) The data were collected by an online survey of 20,096 adults in the US conducted between February and March of 2018. Respondents to the survey yielded data based on two types of variables: (a) demographic and structural, and (b) cognitive and behavioral. We focused on self-reported information on variables of type (a) that included age, gender, race, ethnicity, geographic region, education, presence of children in the household, marital status, employment status, etc. Information on variables of type (b) relevant to this study included social media platform type and usage, perceived social well-being and functioning, self-rated mental health, and overall physical health, etc. Response categories for each of these survey items are described by (Bruce et al., 2019).

In this study, we grouped the age, race, education, and income data from the survey into intuitive categories for our analysis. The age of respondents, recorded as an integer in years, was categorized into 4 groups indexed as: (1) less than 25, (2) 25 to 44, (3) 45 to 64, and (4) 65 or above. The race information was derived as non-Hispanic white (W), black (B), and Hispanic (H), while the remaining categories were combined to a fourth group called “Others” (O). We grouped the education variable into 4 categories as follows: (a) HS: high school or less, (b) SC: some college, (c) BD: bachelor’s degree, and (d) MH: master’s or higher degree. The marital status variable was categorized as (a) SNM: single or never married, (b) MLP: married or living with partner, and (c) WDS: widowed, divorced, or separated. The gender variable was used as originally recorded: male (M) and female (F).

The survey asked the respondents about their use of eight major social media platforms. In this study, we indexed these as (1) Instagram, (2) Snapchat, (3) Twitter, (4) Pinterest, (5) YouTube, (6) LinkedIn, (7) Facebook, and (8) Tumblr. Henceforth, we use these indices 1 through 8 to denote the corresponding platforms. We categorized the responses into 5 frequency levels of social media use indexed in the following order: (1) “Never,” (2) “Less often” or “Every few weeks,” (3) “1–2 times a week,” (4) “3–6 times a week” or “About once a day,” and (5) “Several times a day.”

As a measure of each respondent’s level of loneliness, the survey reported a score based on the well-known UCLA Loneliness Scale (LS) (Russell et al., 1980, 1996). The LS scale includes 20 questions which are grouped into positively and negatively worded questions groups. A positively worded question such as, “How often do you feel that there are people you can talk to?” is paired its negatively worded counterpart, “How often do you feel that people are around you but not with you?” There are four possible answers to each question: “always,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never,” which are scored as 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively, for a positively worded question, while the same for a negatively worded question is reversed. The total LS score for a respondent is in the range of 20 to 80 points, with the mid-point at LS = 50. Thus, higher LS score indicates a greater level of loneliness for the respondent.

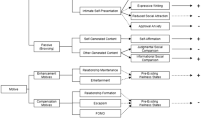

We created a computational pipeline that consists of the following sequence of steps:

-

1.

Clustering of social media use: unsupervised identification of common patterns of social media use by the respondents.

-

2.

Demographic characterization of clusters: test of representation of all possible combinations of age and race groups in the clusters from step 1.

-

3.

Selection of subgroups: using chosen socioeconomic variables to split the demographically characterized clusters from step 2 into corresponding subgroups.

-

4.

Visualization of subgroups: comparison of the distributions of LS scores of subgroups obtained from step 3 using statistics and plots.

Given the significant variation in the frequencies of social media use across different platforms (see Supplementary Fig. S1), for clustering in step 1, we used an agglomerative and sparse hierarchical clustering algorithm described in (Witten & Tibshirani, 2010) with Manhattan distance measure. The algorithm uses an optimization strategy to select the features that contribute significantly to the clustering of social media use data on 8 platforms from the survey respondents.

In step 2, over-representation in a given cluster (identified in step 1) of each of 16 demographic groups (i.e., all \(4\times 4\) combinations of age and race categories) was tested with one-sided chi-square test of association, and its significance determined by a p value threshold of 0.05. In step 3, we split these demographically characterized clusters into different subgroups of interest, such as by gender, or different socioeconomic variables as specified by the user. In step 4, we study the differences in the LS distributions across the selected subgroups. The LS distributions could be compared numerically with Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistics, or using visual aids such as boxplot, density plot, violin plot, empirical cumulative distribution function (ecdf) plot, etc. Survey weights were used in the computation of KS statistics and ecdf plots to allow for comparison of weighted distributions.

Results

During initial processing of survey data, we noted that for a significant proportion of respondents, social media use is predominantly of just one platform. For platforms 1 through 8, we denote the clusters of these “loyal” users as L1–L8, respectively. Further, a significant number of respondents who have minimal use of all the 8 social media platforms were assigned to a cluster denoted by L0. The patterns of social media use in the 8-dimensional data, due to 8 platforms, of the remaining respondents were identified with an agglomerative and sparse hierarchical clustering algorithm as described in the “Data and Methods” section.

Hierarchical clustering is among the most popular methods of unsupervised learning of nested groups in data. Based on the dendrogram produced by our hierarchical clustering, we determined 4 clusters (called 1, 2, 3, 4) representing 4 different patterns of social media use (Supplementary Fig. S2). The median use of the members of each cluster is shown in the radar plot of Fig. 1. Facebook and YouTube were the most significant features that are common across multiple clusters, with Snapchat and Instagram also significant in some of them. Moderate interest in Pinterest and Twitter were also noted. Including the clusters L0 and L1–L8, we obtained a total of 13 clusters of social media use in the survey data, as shown in Table 1. The demographic characterization of each cluster yields the most significantly represented age- and race-groups in each cluster, also shown in Table 1.

Patterns of social media usage of clustered respondents. The radar chart shows the median frequency of use of 8 social media platforms for the members of the clusters 1, 2, 3, and 4. The 5 levels of use of the platforms 1-8 are described in the “Data and Methods” section

For analysis of loneliness data within the context of these social media clusters, a user-friendly procedure allows us to select different parameters of interest to identify subgroups of the cluster members. Thus, we can compare the subgroup-specific distributions of LS scores and other health outcomes using either KS statistics or visual tools. The subgroups could be selected either in parallel or sequential manner. It may be noted that during sequential selection, the sample size of a small subgroup may be further reduced, thereby making it harder for comparing patterns. (We followed a standard abbreviated notation for denoting the subgroups in the Figures and Tables, as shown in the Supplementary Table T1.)

As an example of comparison of subgroups in parallel, we compared the LS distributions of 3 subgrouping criteria: (1) male vs. female, (2) age below 45 years vs. 45 years or above, and (3) marital status SNM vs. MLP vs. WDS. We used these 3 selection criteria to dissect 4 clusters based on the most significant features in clustering, viz., Facebook and YouTube. These clusters are (1) L5: YouTube users (2) L7: Facebook users, (3) 2: users of both platforms, and (4) L0: non-users. This produces an interesting set of results as shown in Fig. 2. We observed that there is no noticeable difference among the male and female LS distributions for clusters 2, L0, or L5 (Fig. 2a, g, and j). Yet, there is a clear difference among the LS distributions for male and female users of Facebook (L7) shown in Fig. 2d. The null hypothesis that these LS distributions are equal was rejected by the KS test (p value = 0.0014).

Comparison of LS distributions across different clusters and subgroups. The x-axis represents LS, and its mid-point is shown with a dashed line. The 4 row panels represent the clusters L5, L7, 2, and L0 from top to bottom. The 3 column panels represent from left to right the subgroup selection criteria: gender, age, and marital status. The LS distributions of the subgroups are shown using different colors in each plot

Notably, the two younger age groups (i.e., 1 and 2) in the survey, as compared to the two older groups (3 and 4), overlap with the popular definition of generations considered “digital natives,” or those who grew up in the “digital age.” Interestingly, when we compared these younger vs. older groups (i.e., of age below 45 years vs. 45 years or above), not only did we observe clear differences in their LS distributions for L5 and L7, but the percentile of high LS (\(\ge 50\)) actually flips from being higher among the younger users of L5 (shown in green in Fig. 2b) to older users of L7 (red in Fig. 2e). That is, lonelier respondents were more common among the younger YouTube users, while the same is true among the older users of Facebook.

Finally, we selected subgroups of the same clusters using marital status as the selection parameter, as shown in Fig. 2 (right column). We observed a pattern that was consistent across all clusters. As is expected, MLP had the least proportion of high LS respondents as compared to those in SNM and WDS in every cluster. Among the last two subgroups, the same proportion was marginally higher for SNM than WDS.

In the next example, given the high representation of older Hispanic respondents in the cluster L7 of Facebook users (see Table 1), we conducted a parallel comparison of loneliness patterns among subgroups of female Hispanic age-group 3 (FH3) users of L7 (denoted by FH3_L7). By fixing FH3_L7 as our reference group, we varied over different choices of parameters Fig. 3. When we fixed the cluster to L7 but varied the FH3 subgroup selection criteria between marital status Fig. 3a and education levels Fig. 3b, we noted that only the former revealed a significant proportion of high LS users in the SNM subgroup shown in green in Fig. 3a. No such distinctive high LS subgroup of FH3 appeared when we fixed the criteria to marital status, and varied the clusters Fig. 3c, d.

Comparison of LS distributions across different subgroup selection parameters. For illustrative example, we use the group FH3 as reference. To compare, we fix the cluster L7 but vary the FH3 subgroup criteria between a marital status and b education; fix the criteria to marital status and vary the clusters to c L0 and d 2. The x-axis represents LS, and its mid-point is shown with a dashed line. The LS cumulative distributions of the subgroups are shown using different colors in each plot

To assess the distinctiveness of the loneliness signature identified above, we varied over multiple selection criteria as another illustration of such parallel comparison. We fixed age, race and cluster but varied the gender to male (Supplementary Fig. S3a); fixed gender, race, and cluster but changed the age group to 4 (Supplementary Fig. S3b); and fixed age, gender, and cluster but varied the race to white and black (Supplementary Fig. S3c, d). While we observed a significant percentile of high LS members among the SNM subgroups in the Supplementary Fig. S3a, c, these were not distinct from the corresponding WDS subgroups.

In our final example, we illustrate the process of sequential selection of subgroups. We begin with comparing the LS densities of non-Hispanic whites across the 4 different age-groups (denoted by W1–W4) and the clusters in which they are significantly represented (see Table 1). In Fig. 4, we noted interesting bimodal distributions for female white (FW) respondents, in contrast to their male counterparts, that have significant peaks of high LS scores (≥ 50). For instance, such bimodal distributions appeared in FW age-groups 2 and 3 of a given cluster L5 (YouTube users). They also appeared in FW age-group 1 of the clusters 3 and 4. Such bimodality could indicate the presence of finer subgroup structures with varying densities of loneliness, which may be revealed by the right choice of socioeconomic parameters used for further dissection.

Comparison of loneliness across clusters, age groups, and sexes. For illustrative example, the data for non-Hispanic whites (W) are shown here, for all 4 age groups a 1, b 2, c 3, and d 4. The violin plots show the densities of LS scores (y-axis) for both males (blue) and females (pink) for the clusters (x-axis) in which the groups are significantly represented. The mid-point of LS is shown with a dotted line

To demonstrate, based on different levels of education, the 4 subgroups selected above reveal interesting variations of LS densities as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. In particular, one group that consistently showed peaks in the high LS (≥ 50) range was “high school or less” (denoted by FW:HS, and shown in green). In the next step, we further probed this FW:HS subgroup based on marital status of its members, as shown in the cumulative distributions of LS in Fig. 5. Notably, the percentile of high LS members is significantly higher for those with marital status SNM (as compared to MLP or WDS) among the FW:HS YouTube users (L5) of age-group 2 Fig. 5a but not of age-group 3 Fig. 5b. In fact, this distinctive high LS signature for SNM L5 users (denoted by FW2:HS:SNM_L5) did not appear in any other FW:HS subgroup (e.g., Fig. 5c, d).

Comparison of LS distributions in subgroups across marital status. The x-axis represents LS scores, and its mid-point is shown with a dashed line. The data for FW:HS are shown. The LS distributions of SNM, MLP, and WDS subgroups are shown in green, red, and blue respectively. Two age-groups a 2 and b 3 are compared across a fixed cluster L5, and two clusters c 3 and d 4 for a fixed age group (1)

We conclude our sequential analysis by comparing the LS distributions across the ordered categories of physical health and mental health of the FW2:HS:SNM_L5 respondents, as shown in Fig. 6. We observed clear and consistent patterns suggesting higher LS to be associated with poorer health outcomes in both cases.

Discussion

A 2018 PEW survey found that while 10% of its respondents reported feeling lonely or isolated, the same rate is considerably higher for low-income Americans (16%) than the high-income group (6%) or for those who have never been married (17%) than those who are married (6%) (Bialik, 2018). Indeed, a large-scale study of a nationally representative sample of US adults aged 19–32 years indicated that perceived social isolation in its study population was greater among single adults and those with lower incomes (Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012). In this study, therefore, we have focused on capturing different aspects of population heterogeneity in a large nationwide survey with the needed computational capacity to gain insights into cluster- or group-specific patterns of loneliness.

Our clustering of data on social media use of respondents revealed a variety of interesting patterns with Facebook and YouTube being selected as the most prominent of features that contributed to the clustering. We observed significant differences in the distributions of high loneliness scores within the subgroups of users of both these platforms defined by age, gender and marital status. We identified particular groups such as predominantly Facebook users who are Hispanic female of age 45–64 years and single or never married to have more significant high loneliness percentile than other comparable subgroups. Similarly, among the group of predominantly YouTube users, we noted that the group of non-Hispanic white female respondents of age 25–44 years who have high school or less education level and are single or never married have more significant high loneliness distribution. In fact, their high loneliness scores also seem to be associated with self-reported poorer physical and mental health outcomes. Such group-specific vulnerability has also been noted by other studies, such as significantly higher suicide rates in the recent years among all women of age 25–44 years in the US (Hedegaard & Curtin, 2018).

It is possible that that the concurrent rise of social media use and loneliness are due to their occurrence at the crossroads of multiple overlapping social psychological processes (Cacioppo et al., 2009). Such factors as the need to belong, self-presentation, and awareness of events in one’s social network could be attributed to popularity of platforms such as Facebook while information seeking, status seeking, and socializing may drive the Twitter users (Quan-Haase & Young, 2010; Nadkarni & Hofmann, 2012; Lee & Ma, 2012). In turn, social media use may lead to a variety of both social as well as individual level behavioral changes and health outcomes for different groups of users. For instance, a group of undergraduate students in the US were found to have significant reductions in loneliness and depression upon limiting their use of social networking sites (Hunt et al., 2018).

Relationships between social media use and loneliness or social isolation remain unclear, and our findings suggest that a deeper focus on group-specific patterns is warranted. In a recently published “biography” of loneliness, the author explored the landscape of this phenomenon as it affects different groups of people and their very specific conditions—from widowhood to old age to homelessness, among others (Alberti, 2019). The pathways through which loneliness may develop in a particular community, and the variety of responses that it may generate from its members, call for detailed studies that are focused on specific groups, and that could inform various psychosocial aspects of healthcare.

Our socioeconomic group dissection approach assumes greater significance in the recent context of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which social isolation may have had divergent effects in different subgroups. In our future work, therefore, we look forward to extending our approach using social network data analysis to identify shared patterns of loneliness and depression—possibly using a social group vulnerability index—as communities worldwide were forced to interact online extensively during their largely isolated, digital existence over the course of the pandemic.

References

Alberti, F. B. (2019). A biography of loneliness. The history of an emotion. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berguno, G., Leroux, P., McAinsh, K., & Shaikh, S. (2004). Children’s Experience of Loneliness at School and Its Relation to Bullying and the Quality of Teacher Interventions. The qualitative report, 9(3), 483–499.

Bialik, K. (2018). Americans unhappy with family, social or financial life are more likely to say they feel lonely. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/12/03/americans-unhappy-with-family-social-or-financial-life-are-more-likely-to-say-they-feel-lonely/ Published 2018. Accessed October 2020.

Bruce, L. D. H., Wu, J. S., Lustig, S. L., Russell, D. W., & Nemecek, D. A. (2019). Loneliness in the United States: A 2018 national panel survey of demographic, structural, cognitive, and behavioral characteristics. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(8), 1123–1133.

Cacioppo, J. T., Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2009). Alone in the crowd: The structure and spread of loneliness in a large social network. Journal of personality and social psychology, 97(6), 977–991.

Calati, R., Chiara, F., Marie, B., et al. (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. Journal of affective disorders, 245, 653-667.

Fakoya, O. A., McCorry, N. K., & Donnelly, M. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 129.

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of behavioral medicine, 40(2), 218–227.

Hedegaard, H., Curtin, S. C., Wagner, M. (2020). Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db330.htm Published 2018. Accessed Dec 2020.

Hobbs, W. R., Burke, M., Christakis, N. A., & Fowler, J. H. (2016). Online social integration is associated with reduced mortality risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 113(46), 12980–12984.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on psychological science, 10(2), 227–237.

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(10), 751–768.

Jaremka, L. M., Fagundes, C. P., Peng, J., et al. (2013). Loneliness promotes inflammation during acute stress. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1089–1097.

Lee, C. S., & Ma, L. (2012). News sharing in social media: The effect of gratifications and prior experience. Computers in human behavior, 28(2), 331–339.

Lykes, V. A., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2014). What predicts loneliness? Cultural difference between individualistic and collectivistic societies in Europe. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(3), 468–490.

Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personal Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266.

Nadkarni, A., & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Why do people use facebook? Personality and individual differences, 52(3), 243–249.

Peplau, L. A., Perlman, D. (1982). Loneliness : A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy. Wiley-Interscience. Volume 36 of Wiley Series on Personality Processes.

Pinquart, M., & Sorensen, S. (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and applied social psychology, 23(4), 245–266.

Pittman, M., & Reich, B. (2016). Social media and loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Computers in Human Behavior, 62, 155–167.

Quan-Haase, A., & Young, A. L. (2010). Uses and gratifications of social media: A comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. Bulletin of science, technology & society, 30(5), 350–361.

Rasmussen, T., Rasmussen, T. (2014). Social capital and social media. In: Personal Media and Everyday Life. Palgrave Macmillan UK; 104-126.

Russell, D. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of personality assessment, 66, 20–40.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of personality and social psychology, 39(3), 472–480.

Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. (2020). https://www.nap.edu/read/25663/chapter/1 Published 2020. Accessed Sep 2020.

Social media - Statistics & Facts. (2020). Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/1164/social-networks/. Accessed Sep 2020.

Steinfield, C., Ellison, N. B., & Lampe, C. (2008). Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of applied developmental psychology, 29(6), 434–445.

Steptoe, A., Shankar, A., Demakakos, P., & Wardle, J. (2013). Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5797–5801.

Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Luchetti, M., & Terracciano, A. (2020). Loneliness and risk of dementia. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(7), 1414–1422.

The “Loneliness Epidemic”. (2020). Health Resources & Services Administration. https://www.hrsa.gov/enews/past-issues/2019/january-17/loneliness-epidemic Published January 2019. Accessed September 2020.

The rise of social media - Our World in Data. (2020). https://ourworldindata.org/rise-of-social-media Accessed Sep 2020.

Weeks, D. J. (1994). A review of loneliness concepts, with particular reference to old age. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 9(5), 345–355.

Witten, D. M., & Tibshirani, R. (2010). A framework for feature selection in clustering. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105(490), 713–726.

Yang, C. (2016). Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: Interact and browse on social media, but don’t compare. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 19(12), 703–708.

Acknowledgements

The loneliness survey data analyzed in the study were provided courtesy of Cigna. SP thanks Donald Burke and Stuart Lustig for their advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gharani, P., Ray, S., Aruru, M. et al. Differential Patterns of Social Media Use Associated with Loneliness and Health Outcomes in Selected Socioeconomic Groups. J. technol. behav. sci. 6, 535–544 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-021-00208-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-021-00208-4