Abstract

This paper aims to describe the context for the migrant camp in a small municipality, and it discusses the challenge of adopting the easyRights information technology (IT) to make it easier for migrants to exercise their human rights. The easyRights project “Enabling immigrants to easily know and exercise their rights” (https://www.easyrights.eu/) is an ongoing European Horizon 2020 project that addresses the challenge of migrant integration through IT-enabled solutions. This project aims to combine co-creation and intelligent language-oriented technologies to make it easier for migrants to understand and access the services to which they are entitled. The easyRights IT–enabled solutions and toolkits for the implementation of inclusion policies can facilitate the management of the integration of migrants, and improve their autonomy and inclusion. Initial interviews with two stakeholders and one migrant in the city of Kavala (in northern Greece) were conducted. Aspects of the information described in this study are intended to be utilized within the Work Package WP7 of the project, which is with regard to the communication and dissemination plan. We recommend for the easyRights IT tools to be adopted in Kavala, so as to facilitate migrants’ exercise of their human rights, and alleviate the tasks of public administrations and local authorities. Possible solutions to avoid migrant marginalization within Kavala’s municipality include adoption of the easyRights IT solutions and investigation of stakeholders’ and migrants’ use of these technology tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the last decade, a large number of migrants, in particular from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, arrived in Greece, due to general political instability and/or war in the region. Although migrants have other countries in Northern and Western Europe as their final destinations, there are around 119,700 refugees and asylum seekers who remain in Greece—mainland and islands (UNHCR, 2021). UNHCR supports the Government of Greece, which leads the refugee response working closely with other United Nations agencies, state institutions, municipalities, international and national NGOs, refugee communities, and local communities. Refugee camps exist in different Greek cities, including Kavala (see Fig. 1) (latitude: 40.94–longitude: 24.42). The municipality of Kavala (https://kavala.gov.gr/?lang=en-gb) is located in the northeastern part of Greece, with a population of 70,501 inhabitants within its administrative boundaries, most of them (around 59,000 inhabitants) living in the city of Kavala. Close to the city center (2.5 km), there is a refugee camp that accommodates approximately 608 migrants-refugees. Migrants who are newcomers to the city encounter and interact with other community members in public space (e.g., streets, transport, schools, community centers), and like any other city inhabitants, they have various needs for employment, education, community services, housing, health care, and transportation. Due to this situation, it is challenging to understand migrants’ settlement and integration processes and experiences at the ground level, such as in small cities/municipalities. As the major service provider, local municipalities play a vital role in providing needed infrastructure and services to support migrant settlement and integration (Zhuang, 2021).

This paper aims to describe the context for the migrant camp in the small municipality of Kavala, and it discusses the challenge of adopting the easyRights information technology (IT) to make it easier for migrants to exercise their human rights. For this purpose, we initially describe the migrant camp in Kavala, and then we present the easyRights project and its information technology (IT) solutions/tools. Afterwards, we discuss the challenge of adopting the IT solutions in this small municipality, and we conclude with some suggestions-recommendations. The term “information and communication technology” (ICT) is treated as synonym to “information technology” (IT), which includes mobile technology/applications as well. Τhe term “migrant integration” refers to the process during which migrants are incorporated into the social structure of the host society; integration aims to improve migrants’ inclusion, autonomy, and sense of belonging.

Migrant Camp: Kavala Long-Term Accommodation Site

The Characteristics of the Camp and its Migrants (It Accommodates)

The migrant camp in Kavala is located in a suburban seaside site 2.5 km away from the center of Kavala and 160 km from Thessaloniki (Greece’s 2nd largest city). The camp covers 61,705.22 m2, and it can accommodate up to 1207 people. Transportation to the Kavala city center and to the hospital is provided by public transportation via bus. There are supermarkets, pharmacies, and other services accessible. For example, the distance to the Citizens’ Service Center (KEP) is 3 km, the distance to the tax office is 3 km, and the distance to ATM is 0.5 km.

According to the latest Site Factsheet (October 2021) published by Supporting the Greek Authorities in Managing the National Reception System for Asylum Seekers and Vulnerable Migrants (SMS), International Organization for Migration (IOM) Office in Greece (https://greece.iom.int/en), the total camp population is 608 people (occupancy: 50.37%) (see Fig. 2) including 135 women (22%), 164 (27%) men, and 309 (51%) children. Regarding nationality breakdown, 81.38% are from Afghanistan, 9.06% from Iraq, 3.62% from Iran (the Islamic Republic of Iran), 2.47% from Syrian Arab Republic, 1.32% from Somalia, and 2.14% other (4 nationalities, less than 1% each). Regarding access to the labor market, 65.22% of the population have a tax number (AFM holders), while 7.49% of the population above 15 years old hold an employment card. Table 1 provides information on the gender and age of camp residents. According to this factsheet, the camp management is represented by the Ministry of Migration and Asylum (until May 2020, the administration was exercised by international organizations and NGOs).

Regarding children’s education, the Formal Education Actor is the Greek Ministry of Education, and the Non-Formal Education (NFE) Actor(s) is UNICEF and Solidarity Now. For refugee children, there is access to local public schools; 348 students were enrolled in Greek public schools (latest available data on the previous academic year 2020–2021). There are also non-formal education services in site, such as NFE courses for minors, and Greek and English language support. Figure 3 is a photo of the camp.

Photo of the camp in Kavala (source: Greek Ministry of Migration and Asylum, https://migration.gov.gr/ris/perifereiakes-monades/domes/domi-kavalas/)

Local Initiatives and Community Debate for Migrants-Refugees

Local initiatives and activities for the migrants living in the camp include cleaning of the beach opposite the camp (Fig. 4) and gardening, as well as sports activities for the children. The beach was cleaned as part of the World Coastal Cleanup Day (17–9-2020). As the local online newspaper reported, at the urging of the staff of the IOM and the cooperation of the cleaning service of the Municipality of Kavala, refugees of the camp took the initiative and cleaned the beach located just opposite the camp’s entrance where they are staying. An IOM executive said: “We are happy because many people registered with the largest percentage being women, who started cleaning the coast. We believe that these actions will continue on our own initiative…We will continue to try, because we want the coexistence of the people who live in the camp with Kavala’s citizens and the whole local community to be harmonious.” The municipality of Kavala provided bags, gloves, and masks, and the refugees collected all the rubbish along the beach, where they spent most of their day with their families during the summer.

Cleaning the beach opposite the camp (source: https://www.lifo.gr/now/greece/prosfyges-kai-metanastes-katharisan-paralia-stin-kabala-opoy-ekanan-mpanio-kalokairi)

Regarding gardening, the manager of the migrant accommodation structure stated: “No one is sitting inside the structure. There are plenty of tasks (to be done) from young and old people. Gardens play a central role. In every camp corner there is a garden with fruits and vegetables, while in other places gardens with roses are prepared.” (Koiveroglou, K-Typos, 2021).

Regarding community debate for migrants-refugees, negative comments are also expressed in the local press. For example,

“A lung on the east side of Kavala, became a small ‘village’ for Afghans in the majority and other migrants, who have not secured, or expect to secure asylum in Greece…Kavala’s citizens, certainly, did not have this vision for the great eastern ‘lung’ of the city” (Proini, 2021).

“The prediction and at the same time concern expressed, a few years ago, by the municipal council of Kavala was verified. At that time, the city council expressed its opposition to the creation of a ‘ghetto’ within the urban fabric. Today, in order for a Kavala citizen, or Media, to enter the camp, the accompaniment of the manager, or an employee is required” (Proini, 2021).

The comments in the local press (Proini, 2021) (several of them anonymous and all written in Greek) reveal that some citizens feel threatened by the migrants’ settlement.

We recommend local policymakers and social workers apply inclusive policies for migrants/refugees. Social workers, as human rights professionals, have been in the forefront of the migration and refugee humanitarian crisis in Greece (social welfare services are part of the local authorities, municipalities, and prefectures). In Greek cities, social and everyday practices (such as housing, childcare practices, and medical treatment) of local authorities/municipalities have played an important role in the implementation of the immigration policy, where refugees were often perceived as a threat to personal and community security; yet, new forms of social mobilization and solidarity by community initiatives have worked to alter these attitudes, mitigating tensions and obstacles in refugee acceptance (Vergou et al., 2021).

The EasyRights Project and Its Information Technology Solutions

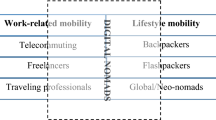

The easyRights project “Enabling immigrants to easily know and exercise their rights” is an ongoing European Horizon 2020 project that addresses the challenge of migrant integration through ICT-enabled solutions. The overarching objective of easyRights is “to develop a co-creative ecosystem in which different actors belonging to the local governance system can cooperate in increasing the quantity and quality of public (welfare) services available to immigrants” (EASYRIGHTS proposal, March 2019). The project is being developed and deployed in four pilot locations including Birmingham (UK), Larissa (Greece), Palermo (Italy), and Malaga (Spain). The specific aims of the project are twofold: (a) to help migrants to use the newly created project services, helping them to work at their own pace, and (b) to allow different stakeholders to assist migrants to work on the services, if migrants ask them to do so (for the project overview, see Concilio et al., 2021, 2022). The project aims to combine co-creation and intelligent language-oriented technologies to make it easier for migrants to understand and access the services to which they are entitled. The easyRights ICT-enabled solutions and toolkits for the implementation of inclusion policies may facilitate the management of the integration of migrants and improve autonomy and inclusion and thus migrants’ lives. Such tools are expected to alleviate the tasks of public administrations and local authorities.

Co-creational approaches often include different actors in terms of practices and scientific fields (i.e., collaboration among designers, IT experts, local service providers, etc.; professionals from diverse fields co-create/design in order), so that new knowledge leading to organizational change can be applied. Intelligent language-oriented easyRights technologies include (a) a personalized vocabulary training mobile app (Capeesh) oriented to train migrants in vocabulary and expressions that can help them better navigate specific services (e.g., seeking for job) and (b) a pronunciation training platform (CALST—Computer-Assisted Listening and Speaking Tutor) that focuses on the most challenging sounds in the local language that might hamper communication. The migrant learners in the easyRights project can be categorized as second-language learners because they are speaking their maternal language first, for instance Arabic, while learning the language spoken in their host country.

Capeesh can provide all language combinations and a highly customizable language learning corpus, e.g., creates numerous contextualized examples of how any given word/phrase/sentence/concept is described in the target language. CALST teaches vocabulary for specific topics which are related to complex procedures that migrants need to deal with in order to achieve inclusion. For example, some sounds can present problems for Arabic speakers learning Greek; CALST offers two types of listening exercises in which phonetically similar sounds are contrasted, in addition to pronunciation and spelling exercises (Nteliou et al., 2021).

Digital inclusion is a human rights issue (Sanders & Scanlon, 2021); therefore, access to easyRights IT constitutes part of migrants’ human rights. It is crucial for migrants to easily exercise their (human) rights. Ease is linked to both (i) improving migrants’ knowledge of their (basic) human rights as a precondition for accessing local welfare services and (ii) communication that involves migrants and service providers (EASYRIGHTS proposal, March 2019).

The Challenge of Adopting the easyRights IT Solutions in Kavala

Municipal governance, policies, infrastructure, and service provisions play a vital role in facilitating migrant settlement and integration. The role and importance of the local socio-political texture in refugee inclusion in Greece was stressed by Vergou et al. (2021). Attention needs to be paid to how the municipality can support migrants in their settlement and integration, so as to secure a sense of belonging and inclusion. Greek gateway cities (e.g., Mytilene, Piraeus) are undergoing changes and facing challenges, by increasing ethno-cultural diversity. Cities have become places where migrants experience civic life, integrate with local economies and communities, and negotiate and claim their rights (Zhuang, 2021).

In Kavala’s case, some internet posts reveal anti-migrant debates and racial tensions, while some citizens feel threatened by the migrants’ settlement. We argue that the municipality must provide explicit policies and services for migrants so as, for example, to ensure that the refugees have equal chances of gaining employment, accessing social work services, and exercising their (human) rights. We argue that the easyRights IT solutions could offer the challenge—and the opportunity—to integrate migrants in local communities. Improving language skills (e.g., via IT apps) is a key precondition for effective inclusion of migrants. Social work and equity are suggested as key goals of Kavala’s municipal programs; i.e., demonstrating the commitment to include migrants/refugees into the planning and community engagement processes. The role of social workers is important especially lately, after the refugee crisis has gained new visibility and increasing complexity. It includes addressing the claims, rights, and needs of refugees (e.g., knowledge of rights for accessing local welfare services), as well as solving conflicts. Social workers need to be equipped with different skills to cope with their demanding duties and also smoothly cooperate with non-governmental organizations, local authorities, etc. For example, local social workers need to work as a team with other professionals such as psychiatrists, psychologists, and administrative officers in order to provide specialized services to migrants (Fylla et al., 2022). A range of activities address the needs of migrants in Greece, including the distribution of clothing and food; accommodation outside the migrant camps; medical and mental health services; educational activities and language classes for adults and children; work-related activities; and legal assistance with access to social rights (Shutes & Ishkanian, 2022). Local social workers help migrants in some such activities, since there is a lack of central planning-coordination of activities in Greece. Among others, social workers are expected to engage in a helping relationship with migrants and help them overcome linguistic and/or cultural barriers. Strong community opposition to planning decisions could emerge due to distrust and/or the lack of communication and engagement. Migrants’ access to social work and educational services may be effectively facilitated via IT. A recent review on mobile learning for refugees (Drolia et al., 2020) indicated that mobile access provides refugees with better access to and quality of education. In the case of Kavala’s municipality, the adoption and usage of appropriate IT (e.g., mobile apps) could prove useful for adult asylum seekers who seek work, for migrant-refugee students (for their education), and for local stakeholders (to facilitate migrant integration process). The needs of minors are also a challenge, since the policy problems in some countries that accommodate migrants neglect the needs of young refugees (Vitus & Jarlbyb, 2021). Aspects of IT solutions are to be used via social media. Research (Alencar, 2018) indicated that social media networking sites were particularly relevant for refugee participants to acquire language and cultural competences; also, the role of government, host society, and the agency of refugees are important actors in determining the way refugees experience social media.

In order to explore the challenge of adopting the easyRights IT solutions in Kavala, we conducted initial interviews with two stakeholders and one migrant in the city of Kavala: the education vice mayor, the camp manager, and one migrant from Afghanistan. Ethical issues were considered; the participation was voluntary, and official permission was obtained from both the easyRights project coordinator and the Greek Ministry of Migration and Asylum. The interviews were conducted in December 2021 and were video-recorded and transcribed by the authors. Although the interviews are not the focus of this paper, we present examples of excerpts with regard to the direct benefit of easyRights IT solutions for the migrants. The vice mayor reported: “It is straight forward that the first barrier that migrants face in their trial for social integration is the language…due to the fact that the average age of public/civil servants is quite high, a great percentage among them does not speak any foreign language, which makes it impossible to serve migrants. Therefore, IT solutions are the only realistic way to serve efficiently those people, thanks to the capability they provide for direct translation between any language.” A migrant commented: “a helpline or support center could be the direct benefit for the migrants,” clarifying that “An application that includes all information about migrants; for example, AFM (tax identification number), AMKA (social security registration number), Refugee stats etc. This application must be in multiple languages, can help migrants to check their stats, appointments etc. quite easily.” The aforementioned views/opinions strengthen our argument for adopting the easyRights IT solutions, in the small municipality. Since we did not collect data with regard to migrants’ literacy or familiarity with digital technologies, we hypothesize that the “digital divide” (typically between young and old; better off and worse off) almost certainly exists within these migrant communities. It is hoped that the ease of use of the apps will facilitate the effective use of the developed technology by these “digital migrants.”

Suggestions to Facilitate ΙΤ Inclusion

We discussed the challenge of adopting the easyRights IT solutions to facilitate migrants’ (human) rights, in the small municipality of Kavala. This city is suggested to participate within the project’s Work Package WP7, which is with regard to the communication and dissemination plan. We conclude with some suggestions-recommendations to facilitate inclusion of migrants/refugees.

-

1.

To investigate and record local leading actors’, municipal stakeholders’ (e.g., vice mayor, migrant camp manager, etc.) and migrants’ use of the easyRights IT tools.

-

2.

To investigate migrants’ perceptions of their needs (e.g., with regard to employment and education), and record their stories.

-

3.

Social work with migrants and refugees is suggested to manage their (un)official activities/tasks and provide resources to facilitate the exercise of their rights.

-

4.

Local policies could consider areas such as community engagement and empowerment, equitable access to resources and services, and dialogue with public forums to share and appreciate diverse perspectives. Initiatives such as migrants’ participation in specific decision-making processes are also important to engage migrants (as is the case for Birmingham-UK, an easyRights pilot city).

-

5.

Policy context is suggested to incorporate the IT solutions, to ease the bureaucratic procedures (migrants’ digital rights are part of human rights). For example, provision of IT-enhanced services for migrants, to ensure they have equal chances of gaining employment.

Our recommendations also initiate future research within the context of the easyRights project and beyond (e.g., for similar small municipalities).

References

Alencar, A. (2018). Refugee integration and social media: A local and experiential perspective. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11), 1588–1603. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1340500

Concilio, G., Costa, G., Karimi, M., Vitaller del Olmo, M., & Kehagia, O. (2022). Co-designing with migrants’ easier access to public services: A technological perspective. Social Sciences, 11(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020054

Concilio, G., Karimi, M., & Rössl, L. (2021). Complex projects and transition-driven evaluation: The case of the easyRights European Project. Sustainability, 13(4), 2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042343

Drolia, M., Sifaki, E., Papadakis, S., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2020). An overview of mobile learning for refugee students: Juxtaposing refugee needs with mobile applications’ characteristics. Challenges, 11(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe11020031

Fylla, I., Fousfouka, E., Kostoula, M., & Spentzouri, P. (2022). The interventions of a mobile mental health unit on the refugee crisis on a Greek island. Psychology, 4(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych4010004

Koiveroglou, K-Typos (2021). “Asimakopoulou” migrant structure: A new district, inside the Perigiali district! https://www.k-tipos.gr/%CE%B4%CE%BF%CE%BC%CE%AE-%CE%BC%CE%B5%CF%84%CE%B1%CE%BD%CE%B1%CF%83%CF%84%CF%8E%CE%BD-%CE%B1%CF%83%CE%B7%CE%BC%CE%B1%CE%BA%CE%BF%CF%80%CE%BF%CF%8D%CE%BB%CE%BF%CF%85-%CE%BC%CE%AF%CE%B1-%CE%BD/

Nteliou, E., Koreman, J., Tolskaya, I., & Kehagia, O. (2021). Digital technologies assisting migrant population overcome language barriers: The case of the EasyRights research project. In P. Zaphiris & A. Ioannou (Eds.), Learning and collaboration technologies: new challenges and learning experiences. HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 12784. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77889-7_8

Sanders, C. K., & Scanlon, E. (2021). The digital divide is a human rights issue: Advancing social inclusion through social work advocacy. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 6, 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-020-00147-9

Shutes, I., & Ishkanian, A. (2022). Transnational welfare within and beyond the nation-state: Civil society responses to the migration crisis in Greece. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(3), 524–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1892479

UNHCR - United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Greece Factsheet (2021, June 2020). Retrieved from https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/84481

Vergou, P., Arvanitidis, P. A., & Manetos, P. (2021). Refugee mobilities and institutional changes: Local housing policies and segregation processes in Greek cities. Urban Planning, 6(2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v6i2.3937

Vitus, K., & Jarlbyb, F. (2021). Between integration and repatriation – frontline experiences of how conflicting immigrant integration policies hamper the integration of young refugees in Denmark. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(7), 1496–1514. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1873112

Zhuang, Z.C. (2021). Cities of migration: The role of municipal planning in immigrant settlement and integration. In Y. Samy & H. Duncan (Eds.), International affairs and Canadian Migration Policy. Canada and International Affairs (pp. 205–226). Palgrave Macmillan: Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46754-8_10

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements to the easyRights project. Some of the ideas developed in this paper were inspired by research conducted in the easyRights. However, the opinions expressed herewith are of the authors.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. This work was supported by easyRights project. The easyRights project is funded by EU Horizon 2020, grant number 870980.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikolopoulou, K., Kehagia, O. & Gavrilut, L. EasyRights: Information Technology Could Facilitate Migrant Access to Human Rights in a Greek Refugee Camp. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 8, 22–28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-022-00233-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-022-00233-0