Abstract

Minimalism is an increasingly popular low-consumption lifestyle whereby people deliberately live with fewer possessions. Proponents of minimalism claim the lifestyle offers a myriad of wellbeing benefits, including happiness, life satisfaction, meaning, and improved personal relationships, however, to date there has been no scientific study examining these claims. The current study aims to take a step towards rectifying this, by exploring the experiences of people living a minimalistic lifestyle. Ten people who identify as minimalists participated in semi-structured interviews to discuss their experience of minimalism and wellbeing. The data was collected and analysed using grounded theory methods. All participants reported that minimalism provided various wellbeing benefits. Five key themes were identified in the study: autonomy, competence, mental space, awareness, and positive emotions. Findings align with previous research examining voluntary simplicity, pro-ecological behaviours, and materialism, and offer new insights into the benefits of low-consumption lifestyles. The results have multidisciplinary implications, from positive psychology to education, business, marketing, economics, conservation and sustainability, with the potential to impact future research, policy, and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Consumerism and materialistic values have potentially negative repercussions for individuals and for society (Kasser 2002). Studies have shown a connection between materialism and a lack of concern about the environment (Hurst et al. 2013), higher financial debt (Gardarsdóttir and Dittmar 2012), and most pertinent to this study, lower levels of personal wellbeing (Dittmar et al. 2014). Low-consumption lifestyles have surged in popularity over the past decade, as people attempt to compensate for the above. One such lifestyle is minimalism, which is characterised by anti-consumerist attitudes and behaviours, including a conscious decision to live with fewer possessions (Dopierała 2017). Proponents of minimalism suggest the lifestyle leads to “happiness, fulfilment, and freedom” (Fields Milburn and Nicodemus n.d.), however, these claims have not been scientifically validated. Furthermore, studies examining low-consumption lifestyles and wellbeing are scarce, with few studies providing a meaningful link between them (Rich et al. 2017b).

The current study aims to understand minimalism by exploring the experience of ‘minimalists’ or people living a minimalistic lifestyle. The intended outcome of the study is to construct a preliminary theory of minimalism from the perspective of positive psychology. Positive psychology is concerned with how and why individuals and groups flourish (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000), and as such, is a fitting platform from which to explore the topic of minimalism and wellbeing. This article provides a summary of the existing literature regarding low-consumption lifestyles and materialism and their relationship to wellbeing; the methods by which the study was conducted; and a detailed discussion of the results, implications, and limitations of the study.

1 Low-Consumption Lifestyles and Wellbeing

People who engage in low-consumption lifestyles and behaviours such as voluntary simplicity, thrift, and pro-ecological behaviours tend to avoid excessive consumption and the acquisition of material possessions. As such, research regarding these lifestyles could provide useful insights for the current study.

Voluntary simplicity is a lifestyle that embraces the core values of material simplicity, self-determination, self-sufficiency, ecological awareness, social responsibility, spirituality, and personal growth (Elgin and Mitchell 1977). While voluntary simplicity appears frequently in scholarly literature, much of the research is criticised for lacking academic rigour and being largely anecdotal, descriptive, and at times speculative (Craig-Lees and Hill 2002; McDonald et al. 2006). Studies often allude to a link between voluntary simplicity and improved wellbeing, yet little empirical evidence has been provided to support this position (Boujbel and D’Astous 2012; Brown and Kasser 2005). In a meta-analysis exploring voluntary simplicity and wellbeing, only four studies were identified in which the link was explicitly examined (Rich et al. 2017a). These studies found that voluntary simplifiers are happier (Alexander and Ussher 2012) and have higher levels of life satisfaction (Boujbel and D’Astous 2012; Brown and Kasser 2005; Rich et al. 2017a), with those who engage in higher degrees of simplifying behaviours experiencing higher levels of life satisfaction (Rich et al. 2017a). Researchers suggest this enhanced life satisfaction is associated with satisfaction of the psychological needs proposed by Deci and Ryan’s (1985) self-determination theory; autonomy, competence, and relatedness; suggesting that psychological need fulfilment mediates the relationship between voluntary simplicity and life satisfaction (Rich et al. 2017a).

Similarly, it has been suggested that the relationship between wellbeing and thrift, “a lifestyle of strategic underconsumption” (Chancellor and Lyubomirsky 2014, pg. 13), is linked to the satisfaction of one’s need for safety, autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Kasser 2011). While this connection has not yet been empirically supported, under this needs-based theory, thrift in some circumstances would satisfy these needs and enhance wellbeing, whereas in other circumstances it would interfere with these needs and diminish wellbeing, which helps to explain some inconsistent findings relating to thrift and wellbeing (Kasser 2011).

Pro-ecological behaviours are those that aim to reduce one’s overall consumption or produce a relatively lower environmental impact (Kasser 2017). Despite pro-ecological behaviours often being framed in terms of self-sacrifice (Jacob et al. 2009) there is increasing evidence suggesting that people who act in an environmentally-conscious manner report higher levels of subjective wellbeing (Binder and Blankenberg 2017; Brown and Kasser 2005; Jacob et al. 2009; Kaida and Kaida 2016; Kasser 2017; Kasser and Sheldon 2002; Suárez-Varela et al. 2016). Evidence indicates that intrinsic value orientation and mindfulness, as well as the fulfilment of the needs of security, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, may explain the positive relationship between wellbeing and pro-ecological behaviours (Brown and Kasser 2005; Kasser 2009). This aligns with findings and theorising relating to wellbeing and its links to voluntary simplicity (Rich et al. 2017a) and thrift (Kasser 2011).

2 Materialism and Wellbeing

While definitions of materialism vary, they consistently contain the notion that possessions are a central focus in materialists’ lives, being viewed as the primary means to life satisfaction and wellbeing and the markers of a successful life (Richins and Dawson 1992). Studies have consistently shown a negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction (Ah Keng et al. 2000; Belk 1984, 1985; La Barbera and Gürhan 1997; Richins and Dawson 1992; Wright and Larsen 1993) as well as in specific domains of life, such as standard of living, family relationships, and leisure (Richins and Dawson 1992). These findings have implications for the current research, given the likelihood that minimalists would not hold materialistic values.

A number of explanations have been proposed for the relationship between materialism and wellbeing (Dittmar et al. 2014). These include negative self-appraisals and social comparisons (Richins 1991; Sirgy 1998); compensating for insecurities or dissatisfaction with life (Fournier and Richins 1991; Richins and Dawson 1992); and failure to satisfy the psychological needs proposed by self-determination theory (Kasser 2002). Research suggests that when these needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness are not met, materialists tend to compensate with possessions (Chang and Arkin 2002; Sheldon and Kasser 2008), perpetuating the cycle of materialism by continually and unsuccessfully attempting to find fulfilment through possession acquisition (Kasser and Ryan 1993). These extrinsic goals do not align with the fulfilment of intrinsic goals of developing autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and as such, result in goals and behaviours that fail to meet these psychological needs (Kasser 2002; Ryan and Deci 2000). These findings provide some support for the wellbeing-related claims of minimalism advocates.

Given the above findings related to materialism and the somewhat limited research into low-consumption lifestyles, exploring the experiences, characteristics, attitudes, and behaviours of people who identify as minimalists is an important step in beginning to understand the mechanisms by which a lifestyle of minimalism may increase well-being.

3 Methods

3.1 Research Design

The limited field of research relating to low-consumption lifestyles and wellbeing is dominated by quantitative studies. Considering this, as well as the lack of research into minimalism specifically and the exploratory nature of the research, qualitative grounded theory methods (Glaser and Stauss 1967) were employed with the objective of developing a preliminary theory of minimalism and wellbeing.

3.2 Participants

There were ten participants in the study, three males and seven females, ranging in age from 24 to 52 years old. The participants resided in the United Kingdom, Australia, the United States of America, Canada, and Germany, and in a range of living situations, including living alone, living with their partner, living with their children, and living in shared accommodation.

Participants were sought through purposeful sampling (Patton 1990) which enabled the researcher to find participants who met participation criteria of self-identifying with the term “minimalist” or identifying as living a minimalistic lifestyle. Participation was sought through social media groups relating to minimalism and through the primary researcher’s personal and professional networks.

Upon expressing interest in the study, potential participants were sent an information letter outlining the study, a short pre-interview questionnaire to gather demographics and to assist in ensuring diversity within the sample, and a consent form. Upon receiving the completed forms, participants were contacted to arrange a suitable time for an interview. Interviews were conducted online via video-conferencing and recorded with the consent of the participant.

3.3 Data Collection and Analysis

Data was obtained through semi-structured interviews, which assisted in guiding participants to remain within the scope of the research, ensured flexibility and responsiveness to new ideas or topics raised, and encouraged deeper exploration, reflection, and clarification (Charmaz 2006; Fielding 1994). Semi-structured interviews also enabled the researchers to apply existing knowledge about minimalism throughout the interview, which assisted in reaching theoretical saturation given institutional time constraints (Rose 1994). The interviews were based on a set of open-ended questions, and additional questions were added and adapted after each interview to explore emerging themes (Charmaz 2006; Strauss and Corbin 1998).

The grounded theory approach necessitates that data collection, analysis, and theorising occur simultaneously and continually from the outset of the research. This process, known as the constant comparative method, enables the systematic development of theory as data collection becomes increasingly focused (Glaser and Stauss 1967). Constant interaction with the data and immediate, continuous analysis allowed for emerging theory to influence later data collection through revising questions and theoretical sampling, whereby pertinent data was actively pursued to fully comprehend the participants’ experiences of minimalism (Glaser and Stauss 1967). The researcher aimed to transcribe and code each interview before the subsequent interview. On occasions when this was not possible, for example when interviews occurred within a short period of time, the researcher listened to the recorded interview and made notes on emerging topics. Due to time constraints, interviews were transcribed using an automated transcription program. To ensure accuracy of the transcription, the researcher reviewed each transcript by listening to the interview audio and editing the transcript as necessary. Each section of the transcript was reviewed several times, which meant the researcher became deeply familiar with the content of the interviews.

A number of coding phases were implemented throughout the study, specifically initial coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding. During initial coding, the researcher coded the data line-by-line and remained open to all possible theoretical directions the data presented. In order to provide clearer, more integrated explanations for the data, focused coding identified and categorised the most prominent and prevalent initial codes. Theoretical coding then involved the researcher postulating possible relationships between the categories, directing the data from the descriptive and analytical into a theoretical perspective (Charmaz 2006; Glaser 1978). This careful, in-depth process ensured the impact of the researcher’s own biases, views, and values was minimised (Charmaz 2006). Concepts and themes revealed through all levels of coding were examined, tested, and refined by comparing incidents and anecdotes for similarities and differences within and across participants.

During data collection and analysis the researcher engaged in memo-writing and diagramming, which served as a tool of analysis, aided in the acceleration of productivity and the development of abstraction, and provided a record of ideas and insights as they were revealed (Charmaz 2006). Codes, theoretical categories, memos, and diagrams were shared and discussed with colleagues throughout the process, to assist in maintaining objectivity and criticality.

Data collection ceased after ten interviews due to institutional constraints, however at this point the interviews were no longer generating insight, nor were they revealing new ideas, suggesting theoretical saturation had been met (Charmaz 2006).

4 Results

All participants indicated that adopting a minimalistic lifestyle afforded a myriad of wellbeing benefits. The key themes and sub-themes (in parentheses) were identified as: Autonomy (freedom/liberation, aligning with values, authenticity); Competence (feeling in control of environment, less stress and anxiety); Mental Space (saving mental energy, internal reflecting external); Awareness (reflection, mindfulness, savouring); and Positive Emotions (joy, peacefulness).

4.1 Autonomy

Self-choosing one’s own behaviour that is congruent with one’s sense of self was a key theme in the study. Sub-themes within autonomy included a sense of freedom and liberation, aligning with one’s values, and a sense of authenticity.

Many participants recalled that before minimalism they felt ‘trapped’, ‘tied down’, or ‘burdened’ by their possessions and by unwanted gifts from others. Participants reported a feeling of freedom and liberation – not only from their possessions, but from societal expectations; from the monotony of routine; and from the trap of the hedonic treadmill, the endless cycle of expecting and adapting to the hedonic pleasure of new purchases (Brickman and Campbell 1971).

We both recognize that when things weren’t good, spending was how we fixed it... it was a quick fix to go out and buy something new. It was a really quick fix. (P7).

I find it’s much easier…and it’s just not as stressful and I don’t have to continually feel like I’m chained to domestic tasks to make my house presentable. (P9).

Many participants, particularly those with children, highlighted saving time as a result of spending less time cleaning and organising, which contributed to this feeling of freedom.

Participants described minimalism as enabling them to become more aware of their values and aligning their actions accordingly. Participants reported various actions that assisted them to become more aligned with their values. These actions included spending more time with family and friends, volunteering, engaging in pro-ecological behaviours and making sustainable and ethical purchases, and choosing to spend money on experiences rather than material objects. One participant recalled dismay at the realisation of the monotony of her family’s routine and lack of quality time with her young child and described how minimalism enabled her to have more meaningful experiences with her family.

I just said to [my husband] one day, ‘There has to be more to life than this. There just has to be.’ [Now] I think we’re feeling more connected as a family…We have stories now. Memories instead of doing the same old thing. (P7).

Aligning one’s values contributed to a feeling of authenticity, which was also a sub-theme of autonomy. Many participants reported that minimalism has supported them to develop a clearer view of their authentic self. A number of participants recognised the idea that stripping back to minimal possessions also enabled them to strip back to their true identity.

I think the process of minimalism and decluttering…brings me closer to my authentic self because it gives me that confidence of knowing what I want and what I don’t want...I’ve got so much more of an idea of what I want for myself and what is going to make me happy. (P10).

I think by becoming a minimalist you become more aware of what really expresses you or what you really value…And I think by having this awareness, you kind of become more authentic. (P4).

The rejection of materialism and consumer culture was evident among participants. Many participants reported they no longer engage in recreational shopping, and almost all participants reported any purchases they now made were strategic, purposeful, and well-researched. While participants tended to reject the materialistic idea that possessions portrayed status, a number of participants reported that the possessions they currently own add joy or value to their lives. As they truly liked and identified with their possessions, they assisted them to feel more authentic.

Possessions before allowed me to be inauthentically something that was more socially acceptable, now my possessions are more an expression of who I consider to be my authentic self. (P8).

4.2 Competence

Feeling effective in one’s environment, or competence, was a key theme that arose from the study. Sub-themes within competence included a sense of control over one’s environment, and reduced anxiety and stress.

When recalling their life before minimalism, a number of participants described ‘chaos’, ‘confusion’, and ‘disorientation’. Minimalism provided a sense of control and the ability to maintain order in their environment, which many indicated was key to their wellbeing.

…And there’s just something about having that level of control of your environment that I think brings me a sense of peace. (P8).

We’re in control of our happiness rather than stuff being in control of us. (P7).

Many participants spoke about feeling stressed, anxious, overwhelmed, or uncomfortable in the presence of clutter. Most participants reported a reduction in stress and anxiety after adopting a minimalistic lifestyle. A number of participants only realised after adopting the lifestyle that their excessive possessions had been a major cause of this stress and anxiety.

I would walk into my [home] office and see the clutter on my desk and see the things all over the walls...I would just feel my heart rate rise, you know…and my chest seize up and I had always just kind of thought, ‘well that’s just how work is’. But now that things are so much more cleared out and it’s just an open space… I don’t have chest tightening from the space…It just makes me breathe easier. (P1).

Others reported that an organised and tidy household was important to their mental health and wellbeing, with minimalism making it easier to maintain this.

4.3 Mental Space

Participants described mental space as a feeling of clear-headedness, of space, lightness, and clarity within one’s mind. Two sub-themes comprise mental space, the connection between the internal and external world, and saving ‘mental energy’.

Almost all participants conveyed the belief that what is happening in one’s physical space (the external world) is reflected in one’s mental space (the internal world) and vice versa. For example, a cluttered, chaotic home was the cause and result of a cluttered, chaotic mind. Participants reported that minimalism provided the means to ‘create space’ in both one’s external and internal world.

If it clutters your physical world, it clutters your mental world. (P3).

There is this interplay between your inner self and your outer environment…and I think that people should be doing a lot more to do what they can to control the outer environment…it reflects who you are on the inside…but also the outside can give you the peace and calm that you need. (P10).

The word ‘purge’ was used by a number of participants to describe decluttering or reducing possessions in one’s physical space, which suggested a feeling of relief. Another participant described feeling renewed when reducing their possessions.

I’ve shucked off my old skin and now I’m moving onto a new phase of living…every time you throw away something you don’t need anymore, it feels like…it can feel like you’re growing and making progress and you’re freeing yourself up. (P8).

Many participants identified the idea of saving ‘mental energy’ as a benefit of minimalism that promotes wellbeing. Participants reported this was due to having fewer choices to make and not pre-occupying the mind with trivial matters.

It’s almost like saving your brain energy by reducing the things that you have to actually think about. Sometimes it’s people just occupying their brain with these things and for me it’s like I just think to myself, ‘God, I’m so glad I don’t have to divert any brain power to those sorts of things’. (P5).

I feel like the decision of what to wear is going to be easier...it’s going to take less time. Like it’s less mental energy. (P7).

4.4 Awareness

As previously mentioned, participants reported that minimalism assisted in raising their awareness of their values and what is important to them. Findings also suggest that the mental space created by minimalism facilitates awareness in other, varying ways. The sub-themes of creating awareness are reflection, mindfulness, and savouring.

Many participants suggested that the mental space resulting from minimalism creates the ideal conditions for reflection, developing new insights, and learning and growing from these insights. Participants reported varying degrees of self-reflection, reflecting on their relationships with others, and reflecting on other aspects of their minimalistic lives, such as how they spend their money, or the environmental impact of their purchases.

It’s been introspective, you know, kind of going through my past. (P1).

…whereas now I try and think a bit more about where that came from or, you know, it’s impact on the environment or that kind of stuff. (P7).

Many participants reported an improved ability to be mindful, that is, more focused on the present moment, and more open and accepting of what is happening in the moment.

I just notice more…because I’m so part of his play now or…just part of his day…he’ll ask for stories about what we’ve done that day and I can tell them because I was present. (P7).

A number of participants reported that they are now more likely to savour the positive experiences in their lives. These participants noted an increase in savouring meaningful exchanges with family and friends, the simple pleasures in life, and their valued possessions.

I think if you put the effort into your possessions and your house and your space, you can just savour the day-to-day. You can savour your daily experiences so much more. (P10).

I would much rather buy something that’s really nice and well-made that I can appreciate and savour and just have one of those rather than have lots of things that are kind of a bit cheap that I don’t really engage with. (P8).

4.5 Increased Positive Emotions

In addition to the absence of stress and anxiety, all participants reported that their minimalistic lifestyle was a catalyst for positive emotions, in particular joy and peacefulness. Positive emotions appeared to stem from the other benefits of minimalism; autonomy, competence, mental space, and awareness.

I’m just not the same person I used to be… I’m very peaceful and calm and very happy. (P3).

A lot calmer. Definitely a lot calmer. (P2).

We’re not spending money, and we’re just having the best time….my heart has sung the last three weekends. (P7).

4.6 Motivation for Minimalism

Motivation towards a minimalistic lifestyle appeared to stem from one of two pathways, attempting to satisfy the need for autonomy or competence. A few participants adopted a minimalistic lifestyle almost as a natural progression from a relatively non-consumerist past. To these participants, minimalism felt autonomous, authentic, and aligned with their values. Becoming minimalist was not necessarily a conscious decision, however maintaining their minimalistic lifestyle required some effort. The main motivation for most participants appeared to be an attempt to fulfil the need of competence; to feel more in control and effective in their everyday lives. Even the people largely motivated by autonomy felt minimalism would fulfil the need for competence.

4.7 A Preliminary Model of Minimalism and Wellbeing

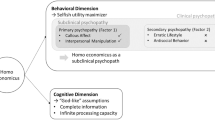

Given the above findings, a preliminary model has been presented in Fig. 1 portraying the possible relationships between minimalism and the key themes.

5 Discussion

The goal of the present study was to explore the experience of people living a minimalistic lifestyle in order to develop a deeper understanding of the wellbeing benefits of minimalism. The participants conveyed a myriad of positive effects on wellbeing, providing evidence to support past research on low-consumption lifestyles, as well as offering new insights into the ways these lifestyles may improve wellbeing. This discussion will examine the findings in reference to previous research and theory, explore the limitations of the study, and make recommendations for future research.

The findings of the current study align with the limited research examining low-consumption lifestyles and behaviours which have generally found that people who engage in such actions have higher levels of personal wellbeing (Boujbel and D’Astous 2012; Brown and Kasser 2005; Kasser 2009, 2011; Rich et al. 2017a). While previous studies explored elements of hedonic wellbeing such as self-reported happiness and life satisfaction, the current study has provided additional insight into how minimalism may enhance eudaimonic wellbeing, a more multidimensional representation of wellbeing (Ryan and Deci 2001).

Aligning with past research relating to materialism and low-consumption lifestyles, psychological needs satisfaction appears relevant to the current study. The key themes of autonomy and competence are supported by self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan 1985; Ryan and Deci 2000), and strengthen findings by Rich et al. (2017a) and theorising by Kasser (2009, 2011) that suggest psychological needs satisfaction may mediate the relationship between low-consumption lifestyles and increased wellbeing. Of particular relevance is cognitive evaluation theory (CET), one of the sub-theories of self-determination theory, which aims to explain intrinsic motivation (Deci and Ryan 1985). CET proposes that, during a particular action, feedback and rewards that promote competence can enhance intrinsic motivation for that action, but only when autonomy is present (Deci and Ryan 1985). This suggests that the feelings of competence experienced when adopting a minimalistic lifestyle, which are accompanied by a sense of autonomy, trigger a cycle of positive reinforcement that further encourages the minimalistic lifestyle. This finding indicates that the benefits of minimalism and other low-consumption lifestyles may only be present if the lifestyle is chosen voluntarily and consciously, and not for those who involuntarily live with fewer possessions, such as people living in poverty or developing countries. The findings relating to autonomy and the sub-themes of freedom/liberation, aligning values, and authenticity support the growing body of research in positive psychology and other disciplines that knowing your true self and acting accordingly promotes subjective and psychological wellbeing (see for example Wood et al. 2008).

The theme of competence and the sub-themes of feeling in control and experiencing less stress and anxiety provide insight into the motivation to adopt minimalism and the wellbeing benefits of the lifestyle. There are a number of possible explanations for the link between minimalism and competence. Minimalists may feel more competent in their environment due to being able to easily locate needed items and not misplacing everyday items such as keys, as described by one participant. Minimalists may be more likely to repair a broken item rather than buy a new one to replace it, an act which could make them feel more competent and is more likely to encourage further competence-inducing acts (De Young 1996). Minimalism may also enhance competence by building life skills in relation to saving money, researching purchases, and practising self-restraint (Kasser 2011). While significant evidence exists connecting a sense of control to a number of physical and psychological benefits (Rodin 1986), contradictory findings suggest that high levels of control may be determinantal (Thompson et al. 1988). While some participants reported unease at being unable to control some elements of their life, such as the purchasing habits of their family, this did not appear to greatly impact the overall benefits of a sense of control in one’s environment. Regarding the final sub-theme of competence, while the absence of stress and anxiety alone does not equate to wellbeing, the absence of mental illness symptoms is an important factor in a complete state of mental health and human flourishing (Keyes 2002).

The key theme of mental space is a notable finding, and while “making space for what matters” is somewhat a catchphrase of minimalist bloggers, there is little discussion regarding mental space in the literature regarding low-consumption lifestyles. The sub-theme regarding the connection between the internal and external world echoes writing by Gregg, who coined the term ‘voluntary simplicity’ and suggested it “involves both inner and outer condition. It means singleness of purpose, sincerity and honesty within, as well as avoidance of exterior clutter, of many possessions irrelevant to the chief purpose of life” (1936, p. 5–6). The findings are reflected in research regarding the negative impact of cluttered homes on subjective wellbeing (Roster et al. 2016), decreased performance and increased stress as a result of the attentional effects of clutter (McMains and Kastner 2011), and a link between clutter and high levels of the stress hormone, cortisol (Arnold et al. 2012). These findings also align with research indicating that cluttered homes and classrooms may be detrimental to attention, cognition, and learning (Fisher et al. 2014; Hanley et al. 2017; Tomalski et al. 2017).

Results indicate participants consider saving ‘mental energy’ as a benefit of minimalism, with several participants suggesting spending less time on clothing choices as an example of this. Self-limiting choices by engaging in minimalism could remedy the ‘tyranny of choice’ which Schwartz (2000) describes as the result of an extreme view of self-determination in which too many choices are overwhelming and daunting. On the other hand, some participants reported partaking in considerable product research before making a purchase, with a few describing this as a painstaking process. Maximisation, that is, examining all alternatives and striving for maximum benefit, is negatively correlated with happiness and life-satisfaction (Schwartz et al. 2002). Findings in the current study suggest that although some minimalists may be maximisers, the wellbeing benefits of minimalism may compensate for any detrimental effects of maximising tendencies.

Participants reported a heightened awareness, and enhanced reflection, mindfulness, and savouring as a result of minimalism. There is substantial evidence suggesting these practices can greatly enhance wellbeing and the experience of positive emotions (Bryant and Veroff 2007; Ivtzan and Lomas 2016). Furthermore, mindfulness enhances the savouring experience (Garland et al. 2015). If one is able to savour the benefits they experience when they adopt minimalism, they may be more likely to experience the full range of wellbeing benefits of the lifestyle.

All of the previous empirical research on low-consumption lifestyles and wellbeing has examined life satisfaction. While the presence of positive emotions is generally included in measures of life satisfaction, no studies have examined the impact of low-consumption lifestyles on positive emotions exclusively. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson 2001) could provide some explanation as to minimalism’s effect on positive emotions. The theory proposes that the experience of positive emotions encourages the broadening of one’s mind, which enables creativity and flexible, and in turn builds one’s personal resources. The feelings of competence and autonomy, as well as peacefulness and joy that result from minimalism, could therefore be seen as a catalyst creating awareness and capacity building, which could in turn further encourage a minimalistic lifestyle.

5.1 Limitations and Future Directions

A number of limitations of the current study should be considered when examining the results and conclusions. While the ten participants differed in geographical location, age, occupation, marital status, parental status, and living arrangements, they were all from Western developed countries and similar socio-economic backgrounds. While people from lower socio-economic backgrounds or developing nations may engage in low consumption as a necessity rather than a lifestyle choice (Alexander and Ussher 2012), they may still be subject to the same consumer messages and consumption desires. Future research could include participants from developing countries and low socio-economic backgrounds to determine whether the attitudes associated with minimalism, such as rejection of materialism, could improve the wellbeing of those already living with less. Furthermore, given the popularity of minimalistic lifestyles in Japan (Kondo 2011; Sasaki 2017), future studies could aim to include participants from Eastern countries. There were substantially more female (seven) than male (three) participants, and while future research could aim to include more male participants, other studies examining low-consumption lifestyles have also had a higher number of female participants (Alexander and Ussher 2012; Boujbel and D’Astous 2012; Breen Pierce 2000; Huneke 2005; Rich et al. 2017a). This could indicate that females are more likely to engage in minimalism or are more likely to participate in research about their lifestyle.

The current research required people to self-identify as minimalists, which could be a limitation as there is no set definition of minimalism. While some view minimalism as an anti-consumerist lifestyle that encourages finding meaning in life beyond the material (Dopierała 2017) or simply valuing fewer possessions (Alexander and Ussher 2012), others view minimalism as voluntary simplicity’s ‘second-wave’ or use the terms interchangeably (Kasperek, 2014, as cited in Dopierała 2017). In contrast, some argue that a set definition is conflicting with the lifestyle, as becoming a minimalist requires “building and sustaining one’s own self-definition” (Dopierała 2017, p. 69). Variance between participants as to their motivation towards minimalism, the extent of their minimalism, and the length of time they had been engaged in the lifestyle could play a factor in their reported wellbeing (McDonald et al. 2006). This heterogeneity has been problematic in studies of voluntary simplifiers, and researchers have attempted to reconcile this by testing for differences between groups based on characteristics from the literature, or by using a measure of voluntary simplicity values (Boujbel and D’Astous 2012; Brown and Kasser 2005). However, no such measure exists for minimalism, and it could be premature to identify characteristics of minimalists beyond ‘has made a conscious decision to live with fewer possessions.’ More research regarding minimalism and the characteristics of minimalists specifically is required before sample selection by self-identification is obsolete.

Despite all participants reporting an overwhelmingly positive outlook on minimalism and its relationship to wellbeing, a number of less positive stories came to light, such as a heightened sensitivity to clutter, worry about acquiring possessions after the death of family members, and painstaking research before purchasing a product. While it was beyond the scope of the current study, future research could investigate whether different personality traits, such a need for control, neuroticism, and maximising tendencies, impact the experience of minimalism and, in turn, the wellbeing of minimalists. Research on personality could also assist in determining whether particular types of people are attracted to a lifestyle of minimalism, and whether some people may not experience the wellbeing benefits espoused by the participants in the current study and other advocates of the lifestyle.

The empirically unexplored subject of minimalism has benefited from this research, however, as the title suggests, the proposed theory is tentative – a step towards developing a more thorough, robust theory. Quantitative, correlational research could assist to further substantiate the theory, and experimental methods could test the effects of minimalism on wellbeing and establish causal relationships. The development and validation of minimising techniques as positive psychology interventions would be a valuable addition to the literature, and to the field of positive psychology as a whole.

The findings of the current study relating to minimalism and wellbeing have implications across multiple disciplines besides psychology, such as education, business, marketing, economics, and perhaps most importantly, conservation and sustainability. Many people express concern over issues such as climate change, loss of biodiversity, deforestation, and pollution, yet the vast majority fail to modify their consumerist lifestyles. While some suggest this gap between attitude and behaviour could be alleviated through examining marketing and social policy (Kilbourne and Pickett 2008), some suggest that until the association between material possessions and wellbeing is eliminated, it is unlikely that people will adopt low-consumption lifestyles (Kasser 2017). Perhaps an understanding of the wellbeing benefits of minimalism can provide the encouragement to reduce individual consumption and ultimately lessen the population’s ecological footprint.

References

Ah Keng, K., Jung, K., Soo Jiuan, T., & Wirtz, J. (2000). The influence of materialistic inclination on values, life satisfaction and aspirations: An empirical analysis. Social Indicators Research, 49(3), 317–333 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27522439.

Alexander, S., & Ussher, S. (2012). The voluntary simplicity movement: A multi-national survey analysis in theoretical context. Journal of Consumer Culture, 12(1), 66–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540512444019.

Arnold, J. E., Graesch, A. P., Ragazzini, E., & Ochs, E. (2012). Life at home in the twenty-first century: 32 families open their doors. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Belk, R. W. (1984). Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. Advances in Consumer Research, 11, 291–297 Retrieved from http://acrwebsite.org/volumes/6260/volumes/v11/NA-11.

Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 265. https://doi.org/10.1086/208515.

Binder, M., & Blankenberg, A. K. (2017). Green lifestyles and subjective well-being: More about self-image than actual behavior? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 137, 304–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.03.009.

Boujbel, L., & D’Astous, A. (2012). Voluntary simplicity and life satisfaction: Exploring the mediating role of consumption desires. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 11, 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1399

Breen Pierce, L. (2000). Choosing simplicity: Real people finding peace and fulfillment in a complex world. Carmel: Gallagher Press.

Brickman, P., & Campbell, D. T. (1971). Hedonic relativism and planning the good society. In M. H. Appley (Ed.), Adaptation level theory: A symposium (pp. 287–302). New York: Academic.

Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8207-8.

Bryant, F. B., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). Money for happiness: The hedonic benefits of thrift. In M. Tatzel (Ed.), Consumption and well-being in the material world (pp. 13–47). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7368-4_2.

Chang, L., & Arkin, R. M. (2002). Materialism as an attempt to cope with uncertainty. Psychology and Marketing, 19(5), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10016.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Craig-Lees, M., & Hill, C. (2002). Understanding voluntary simplifiers. Psychology and Marketing, 19(2), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10009.

De Young, R. (1996). Some psychological aspects of reduced consumption behavior: The role of intrinsic satisfaction and competence motivation. Environment and Behavior, 28(3), 358–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916596283005.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 879–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037409.

Dopierała, R. (2017). Minimalism – A new mode of consumption? Przegląd Socjologiczny, 66(4), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.26485/PS/2017/66.4/4.

Elgin, D., & Mitchell, A. (1977). Voluntary simplicity. CoEvolution Quarterly, 3, 2 Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313754669_Voluntary_Simplicity_in_Co-Evolution_Quarterly_1977.

Fielding, N. (1994). Varieties of research interviews. Nurse Researcher, 1(3), 4–13.

Fields Milburn, J., & Nicodemus, R. (n.d.). The Minimalists. Retrieved 15 Jan 2018, from https://www.theminimalists.com

Fisher, A. V., Godwin, K. E., & Seltman, H. (2014). Visual environment, attention allocation, and learning in young children: When too much of a good thing may be bad. Psychological Science, 25(7), 1362–1370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614533801.

Fournier, S., & Richins, M. L. (1991). Some theoretical and popular notions concerning materialism. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6(6), 403–414.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218.

Gardarsdóttir, R. B., & Dittmar, H. (2012). The relationship of materialism to debt and financial well-being: The case of Iceland’s perceived prosperity. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(3), 471–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.12.008.

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P. R., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294.

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley: The Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Stauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Gregg, R. B. (1936). The value of voluntary simplicity. Portland: The Floating Press.

Hanley, M., Khairat, M., Taylor, K., Wilson, R., Cole-Fletcher, R., & Riby, D. M. (2017). Classroom displays-attraction or distraction? Evidence of impact on attention and learning from children with and without autism. Developmental Psychology, 53(7), 1265–1275. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000271.

Huneke, M. E. (2005). The face of the un-consumer: An empirical examination of the practice of voluntary simplicity in the United States. Psychology and Marketing, 22(7), 527–550. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20072.

Hurst, M., Dittmar, H., Bond, R., & Kasser, T. (2013). The relationship between materialistic values and environmental attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 36, 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.09.003.

Ivtzan, I., & Lomas, T. (Eds.). (2016). Mindfulness in positive psychology: The science of meditation and wellbeing. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jacob, J., Jovic, E., & Brinkerhoff, M. B. (2009). Personal and planetary well-being: Mindfulness meditation, pro-environmental behavior and personal quality of life in a survey from the social justice and ecological sustainability movement. Social Indicators Research, 93(2), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl1205-008-9308-6.

Kaida, N., & Kaida, K. (2016). Pro-environmental behavior correlates with present and future subjective well-being. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9629-y.

Kasperek, A. (2014). Wyrażanie sprzeciwu poprzez duchowość. przypadek minimali- zmu”. Stan Rzeczy 2:179–197.

Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kasser, T. (2009). Psychological need satisfaction, personal well-being, and ecological sustainability. Ecopsychology, 1(4), 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2009.0025.

Kasser, T. (2011). Can thrift bring well-being? A review of the research and a tentative theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(11), 865–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00396.x.

Kasser, T. (2017). Living both well and sustainably: A review of the literature, with some reflections on future research, interventions and policy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 375(2095). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2016.0369.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410.

Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2002). What makes for a merry Christmas? Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(August), 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021516410457.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197.

Kilbourne, W., & Pickett, G. (2008). How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Business Research, 61(9), 885–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.09.016.

Kondo, M. (2011). The life-changing magic of tidying. London: Vermilion.

La Barbera, P. A., & Gürhan, Z. (1997). The role of materialism, religiosity, and demographics in subjective well-being. Psychology and Marketing, 14(1), 71–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199701)14:1<71::AID-MAR5>3.0.CO;2-L.

McDonald, S., Oates, C. J., Young, C. W., & Hwang, K. (2006). Toward sustainable consumption: Researching voluntary simplifiers. Psychology and Marketing, 23(6), 515–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20132.

McMains, S., & Kastner, S. (2011). Interactions of top-down and bottom-up mechanisms in human visual cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(2), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3766-10.2011.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Rich, S. A., Hanna, S., & Wright, B. J. (2017a). Simply satisfied: The role of psychological need satisfaction in the life satisfaction of voluntary simplifiers. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9718-0.

Rich, S. A., Hanna, S., Wright, B. J., & Bennett, P. C. (2017b). Fact or fable: Increased wellbeing in voluntary simplicity. International Journal of Wellbeing, 7(2), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v7i2.589.

Richins, M. L. (1991). Social comparison and the idealized images of advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1086/209242.

Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1086/209304.

Rodin, J. (1986). Aging and health: Effects of the sense of control. Science, 233(4770), 1271–1276. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3749877.

Rose, K. (1994). Unstructured and semi-structured interviewing. Nurse Researcher, 1(3), 23–32.

Roster, C. A., Ferrari, J. R., & Jurkat, M. P. (2016). The dark side of home: Assessing possession “clutter” on subjective well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 46, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.03.003.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141.

Sasaki, F. (2017). Goodbye, things: On minimalist living. London: Penguin.

Schwartz, B. (2000). Self-determination: The tyranny of freedom. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.79.

Schwartz, B., Ward, A., Monterosso, J., Lyubomirsky, S., White, K., & Lehman, D. R. (2002). Maximizing versus satisficing: Happiness is a matter of choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1178–1197. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1178.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5.

Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (2008). Psychological threat and extrinsic goal striving. Motivation and Emotion, 32, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9081-5.

Sirgy, M. J. (1998). Materialism and quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 43(3), 227–260 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27522311.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Suárez-Varela, M., Guardiola, J., & González-Gómez, F. (2016). Do pro-environmental behaviors and awareness contribute to improve subjective well-being? Applied Research in Quality of Life, 11(2), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-014-9372-9.

Thompson, S., Cheek, P., & Graham, M. (1988). The other side of perceived control: Disadvantages and negative effects. In S. Spacapan & S. Oskamp (Eds.), The social psychology of health (pp. 69–93). Newbury Park: Sage.

Tomalski, P., Marczuk, K., Pisula, E., Malinowska, A., Kawa, R., & Niedzwiecka, A. (2017). Chaotic home environment is associated with reduced infant processing speed under high task demands. Infant Behavior & Development, 48, 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.04.007.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Baliousis, M., & Joseph, S. (2008). The authentic personality: A theoretical and empirical conceptualization and the development of the authenticity scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.385.

Wright, N. D., & Larsen, V. (1993). Materialism and life satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction, and Complaining Behavior, 6, 158–165 Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284155427.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (University of East London School of Psychology Research Ethics Committee) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lloyd, K., Pennington, W. Towards a Theory of Minimalism and Wellbeing. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 5, 121–136 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-020-00030-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-020-00030-y