Abstract

Introduction

An integrated analysis was performed using safety data from 18 randomized, parallel-group studies from the fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (FF/VI) GSK asthma clinical study program. Efficacy data from four pivotal studies were also analyzed.

Methods

Data were integrated from 18 Phase IIb and Phase III clinical studies. Key treatment arms were FF/VI 200/25 µg, FF/VI 100/25 µg, FF 200 µg, FF 100 µg, VI [with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs)] 25 µg, and placebo. Safety endpoints included adverse events (AEs), AEs of special interest, 24-h urinary cortisol, vital signs, electrocardiograms, and asthma composite endpoints (defined as asthma-related hospitalizations, intubations, or death). Key efficacy endpoints included lung function assessments and symptomatic measures.

Results

In total, 7229 patients were randomized to one of six key treatment groups. The most frequently experienced AEs across key treatment groups were headache, nasopharyngitis, and upper respiratory tract infection. A greater incidence of local steroid effects was reported with FF-containing treatment groups versus placebo. No statistically significant difference was observed in asthma composite endpoint (asthma-related hospitalizations, intubations, or death) analysis of all FF/VI doses versus all ICS doses. A statistically significant difference in trough forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), 0–24 h weighted mean FEV1, and rescue-free and symptom-free 24 h periods was reported between FF/VI and FF treatment groups in all studies except one (NCT01165138).

Conclusion

There was no evidence of an increased safety risk associated with FF/VI versus FF, VI, or placebo. FF/VI improved lung function and symptomatic endpoints versus FF alone. These data support the positive benefit:risk ratio of FF/VI versus FF alone and of having two approved FF/VI strengths to ensure appropriate treatment for patients with different asthma severity.

Funding

GSK.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases with an estimated 300 million people diagnosed worldwide [1]. International guidelines for asthma treatment recommend the combination of long-acting β2-receptor agonist (LABAs) with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) as maintenance therapy in patients who remain symptomatic despite receiving low-to-medium doses of ICSs [1, 2].

Although many treatment options are available, asthma morbidity remains high, with an estimated 346,000 deaths annually worldwide [1, 3]. Despite treatment, the incidence of uncontrolled asthma remains high with a recent European survey of 8000 subjects with asthma showing that 45% of patients with asthma had uncontrolled disease [4]. Poor control often limits activity, and causes breathlessness and sleep difficulties. Patients with poorly controlled disease also experience more absenteeism and work impairment than those with asthma that is at least well controlled [4].

Asthma-related deaths, increased exacerbations, and poor disease control have been associated with non-adherence to medication [5], which is reported to be common in this patient population [6, 7]. A report from the UK suggested that 65% of asthma-related deaths occurring between February 2012 and January 2013 were due to patient-related factors, including non-adherence to medication [8]. Non-adherence to medication is a key factor contributing to poor disease control, which leads to more frequent visits to healthcare professionals, an increase in healthcare costs, and a reduction in health-related quality of life [9] and may be improved with once-daily dosing [10].

GSK has conducted a large complex program of Phase II and III clinical studies in more than 12,000 adults and adolescents with asthma to evaluate the efficacy and safety of fluticasone furoate/vilanterol (FF/VI), a once-daily ICS/LABA combination therapy administered as a single fixed dose using the ELLIPTA® dry powder inhaler (GSK, Brentford, London). Two doses of FF/VI (200/25 and 100/25 µg) have been approved as maintenance therapy for patients with asthma in the USA [11], Europe [12–14], Japan [15], and a number of other countries. The availability of two FF/VI strengths provides flexible treatment options to meet the individual needs of patients.

This paper presents an integrated analysis of safety data collected from 18 randomized, parallel-group studies that were part of the FF/VI GSK clinical study program. In addition, efficacy data from four pivotal studies have been evaluated and will be presented to allow a benefit:risk assessment, including an integrated efficacy analysis for forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) by demographic subgroups. Furthermore, greater comprehension of the safety, efficacy, and benefit:risk ratio of FF/VI, administered as a single fixed dose in a large patient population, will add to the clinical understanding of this therapy.

Methods

Clinical Studies

Four Phase IIb and 14 Phase III randomized, double-blind, parallel-group studies with FF/VI and/or an individual component (FF or VI) were included in this integrated safety analysis. The study designs are summarized in Supplementary Table 1; briefly FF/VI (200/25 or 100/25 µg), FF (200 or 100 µg), and VI 25 µg on a background of ICSs [VI (ICS) 25] were administered once-daily in the evening using the ELLIPTA inhaler. In ten of these studies, active comparators [fluticasone propionate (FP 500, 250, or 100 µg), salmeterol (SAL 50 µg) on an ICS background, or FP/SAL (250/50 µg)] were administered twice-daily using the DISKUS™ inhaler (GSK, Brentford, London). All active treatment doses are presented in micrograms (µg). Patients were provided with albuterol/salbutamol to be used as rescue medication throughout the study when and as required. The key treatment groups in this integrated analysis were: FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, FF 200, FF 100, VI (ICS) 25, and placebo. Only data from these key groups are presented.

Data from the following 18 clinical studies were used in this integrated analysis: NCT00603746 (FFA109684) [16], NCT00603278 (FFA109685) [17], NCT00603382 (FFA109687) [18], and NCT00600171 (B2C109575) [19] are Phase IIb studies; NCT01165138 (HZA106827) [20], NCT00134042 (HZA106829) [21], NCT01686633 (HZA116863) [22], NCT01086384 (HZA106837) [23], NCT01498653 (HZA113714) [24], NCT01498679 (HZA113719; data on file), NCT01147848 (HZA113091) [25], NCT01436071 (FFA115283) [26], NCT01436110 (FFA115285) [27], NCT01159912 (FFA112059) [28], NCT01431950 (FFA114496) [29], NCT01181895 (B2C112060) [30], NCT01018186 (HZA106839) [31], and NCT01086410 (HZA106851) [32] are Phase III studies.

Across all studies, eligible patients were ≥12 years of age and had been diagnosed with persistent asthma. Other inclusion criteria included a predicted pre-bronchodilator FEV1 of 40–90% (≥50% in NCT01086410 and NCT01018186, ≥60% in NCT01436071 and NCT01436110, 40–80% in NCT01686633, 40–85% in NCT01147848, and 50–90% in NCT01086384), and FEV1 reversibility of ≥12% and ≥200 mL within 10–40 min, following 200–400-µg albuterol/salbutamol inhalation. In addition, all patients in NCT01086384 must have experienced one or more asthma exacerbations requiring treatment with oral corticosteroids in the previous year. This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Safety Analyses

Safety analyses were performed on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which was defined as all patients who were randomized and had received at least one dose of study medication during the treatment period. The urinary cortisol (UC) population is defined as the population of primary interest for 24-h UC analyses. The safety endpoints assessed included adverse events (AEs), AEs of special interest (AESIs), 24-h UC, vital signs, electrocardiograms, and an asthma composite endpoint (defined as asthma-related hospitalizations, intubations, or deaths).

AEs were coded and grouped by system organ class and preferred term using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA V16.1 [IFPMA (Geneva, Switzerland)]). AEs that were assessed by the investigator as having a reasonable possibility of being caused by the study medication were termed ‘drug-related’. For all analyses, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used as appropriate. When significance testing was carried out, a two-sided test was used at the 0.05 significance level.

AESIs were defined using pre-selected MedDRA V16.1 preferred terms and based on the known drug class AE profile or pharmacology of corticosteroids [i.e., hypersensitivity, bone disorders, local steroid effects (e.g., oral candidiasis, hoarseness), ocular effects, glucose effects, pneumonia, lower respiratory tract infections, and systemic effects (e.g., hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis)] and LABAs (i.e., cardiovascular effects, effects on potassium, effects on glucose). Analysis of AESIs was performed using Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel corrected percentages of patients to compare each FF dose versus placebo, FF/VI 200/25 versus FF/VI 100/25, FF/VI 100/25 versus FF 100, and FF/VI 100/25 versus placebo.

For the composite endpoint, all serious AEs (SAEs) for studies that included VI, either as a monotherapy on a background of ICSs or as part of FF/VI, were assessed by an independent adjudication panel blinded to both treatments whether the event was respiratory-related or not respiratory-related. Respiratory-related events were further assessed as being asthma-related or not asthma-related. Five crossover studies (NCT01453023 [FFA112777], NCT01128569 [FFA113090], NCT01128595 [FFA113126], NCT00980200 [FFA113310], and NCT01287065 [FFA114624]) and an open-label clinical study (NCT01244984 [FFA113989]), which were not included in the integrated analysis, were used (in addition to the Phase IIb and Phase III studies) in the asthma composite endpoint adjudication and analysis to ensure that all available data on VI-containing studies were included.

Efficacy Analyses

Efficacy data from the following four pivotal Phase III studies are described: NCT01165138, NCT01134042, NCT01686633, and NCT01086384. All analyses were performed using the ITT population. Key efficacy endpoints included lung function assessments (trough and weighted mean FEV1) and symptomatic measures (rescue- and symptom-free 24-h periods). Results were shown as treatment differences, least squares means, 95% CI, and p values. Due to the differences between the four studies (i.e., study design and study populations), efficacy findings will focus on the individual studies. Data showing trough FEV1 at week 12 were integrated to facilitate efficacy evaluation by the following subgroups: gender, age, race, and region.

Results

The cut-off date for all data included in this analysis was 31 January, 2014. A total of 9919 (>99%) patients received ≥1 dose of study medication (Fig. 1). The ITT population for this integrated analysis comprised 7229 patients who were randomized to one of the six key treatment groups: FF/VI 200/25 (n = 956), FF/VI 100/25 (n = 2369), FF 200 (n = 608), FF 100 (n = 2010), VI (ICS) 25 (n = 216), and placebo (n = 1070). The majority of these patients received either FF/VI 100/25 or FF 100. The VI (ICS) 25 group contained the smallest number of patients, as this treatment was only included in two studies. Across the studies, 84% of patients in the key treatment groups completed the study and 16% withdrew prematurely. Lack of efficacy was the most common reason for withdrawal in all groups except for FF/VI 100/25; 23% of patients in the placebo group withdrew citing this reason. In the FF/VI 100/25 group, withdrawal of consent was the most common reason for withdrawal (reported by 4% of patients). Other reasons for withdrawal, such as protocol deviation and AEs, were reported by ≤2% of patients within each treatment group.

Demographic characteristics for the key treatment groups are provided in Table 1. The proportion of males to females and the mean age were similar across these groups. The majority of patients in each treatment group were aged 18–64 years and the majority were Caucasian. The mean duration of asthma ranged from 15 to 18 years.

Cumulative exposure varied widely across the key treatment groups, which is likely to reflect the differing duration of these studies (range of 4–76 weeks). The highest exposure was reported for the FF/VI 100/25 group (1537 patient years; key treatment groups displayed in Table 2). More than half (59%) of the FF/VI 100/25 patients were in studies of ≥24 weeks’ duration. As patients may not receive a long-term placebo, no patient was exposed to placebo for more than 28 weeks. Most (63%) of the patients who were randomized to receive placebo were in studies of <12 weeks’ duration.

Safety Analysis

The most frequently reported common AEs were headache, nasopharyngitis, and upper respiratory tract infection (key treatment groups displayed in Table 3). The incidence of some events was numerically higher in the FF/VI 100/25 group compared with the placebo group. However, there was no notable difference in exposure-adjusted incidence across treatment groups with the exception of oropharyngeal pain, for which the incidence was numerically greater in the FF/VI 200/25 group than the FF/VI 100/25 group, and back pain, which was reported at a numerically higher incidence in all active treatment groups compared with placebo.

Figure 2a presents the incidence of AEs reported by ≥3% of patients for FF/VI 100/25 compared with placebo (in those studies that included both FF/VI 100/25 and placebo) and shows that the incidence is similar (95% CI for the risk ratio included 1) for nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection, and favored placebo for headache. When the incidence of any AE reported by ≥3% of patients for FF/VI 100/25 was compared with FF 100, there was no evidence of a significant difference as the 95% CI for the risk ratio includes 1 (Fig. 2b). There is also no evidence of an increase in the incidence of any AEs reported by ≥3% of patients for FF/VI 200/25 compared with FF/VI 100/25 (Fig. 2c).

Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel adjusted commonly experienced (≥3%) on-treatment AEs by relative risk for a FF/VI 100/25 versus placebo (including: NCT01165138, NCT01086410, and NCT01498679), b FF/VI 100/25 versus FF 100 (including: NCT01165138, NCT01086384, and NCT01686633), and c FF/VI 200/25 versus FF/VI 100/25 (including: NCT01018186, NCT01086410, and NCT01686633). AE adverse event, CI confidence interval, FF fluticasone furoate, OD once-daily, VI vilanterol

The incidence of any drug-related AE (based on investigator opinion) was 6% in the FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, FF 200, and FF 100 groups, and 2% in the VI (ICS) 25 group, compared with 2% in the placebo group (Table 4). Among the drug-related AESIs, oral candidiasis had the highest incidence in the FF/VI 200/25 group (2%) compared with 0% in the placebo group, <1% in the FF/VI 100/25 and FF 100 groups, and 1% in the FF 200 group. The incidence of other drug-related AESIs was low across all groups [dysphonia: 1% with FF/VI 100/25, <1% with FF/VI 200/25, FF 100, FF 200, and placebo, 0% with VI (ICS) 25; oropharyngeal candidiasis: 1% with FF 200, <1% with FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, FF 100, and placebo, 0% with VI (ICS) 25; oropharyngeal pain: <1% with FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, FF 200, FF 100, and placebo, 0% with VI (ICS) 25; and bronchitis: <1% with FF/VI 100/25 and FF 100, 0% with FF/VI 200/25, FF 200, VI (ICS) 25, and placebo].

No differences were observed in the incidence of SAEs between the FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, FF 200, FF 100, and VI (ICS) 25 groups, and the placebo group (Table 5). Across the FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, FF 200, and FF 100 groups, seven patients experienced SAEs considered by the investigator to be related to study medication: one patient in the FF/VI 200/25 group (atrial fibrillation); two patients in the FF/VI 100/25 group (tachyarrhythmia and atrial fibrillation); and four patients in the FF 100 group (non-cardiac chest pain, asthma exacerbation, pleurisy, and pneumonia). Four deaths were reported. One patient died in the FF/VI 100/25 group (road accident) and two in the FF 100 group (stage IV lung cancer, and sepsis and pneumonia); none of these was determined to be asthma-related or considered to be related to the study medication. One patient in the placebo group died of an unknown cause.

The incidences of AESIs across the key treatment groups are presented in Table 6. The incidence of local steroid effects was numerically higher with FF-containing treatment arms (7–8%) compared with placebo (2%). The incidence of lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in the FF/VI 200/25 and FF/VI 100/25 groups was 3% and 4%, respectively, compared with 2% in the placebo group, and 3% and 6% in the FF 200 and FF 100 groups, respectively, with the rate of bronchitis events (5%) being the main factor in the FF 100 group. Symptoms that may be associated with hypersensitivity reactions were observed at a similar incidence across the groups [2% with FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, FF 100, and placebo; <1% with FF 200 and VI (ICS) 25].

The exposure-adjusted incidence of local corticosteroid effects, pneumonia and LRTIs, cardiovascular effects, and hypersensitivity reactions was numerically higher within the FF/VI 200/25 group versus the FF/VI 100/25 group. A numerically greater exposure-adjusted incidence of local steroid effects was observed with FF 200 (283.8/1000 patient years) versus FF 100 (104.5/1000 patient years), and with FF/VI 200/25 (183.2/1000 patient years) versus FF/VI 100/25 (100.8/1000 patient years). A numerically greater exposure-adjusted incidence of cardiovascular events was experienced in the FF/VI 200/25 group (120.4/1000 patient years) compared with the FF/VI 100/25 group (66.3/1000 patient years). This was influenced by the higher number of extrasystoles observed in study NCT01018186 during Holter monitoring, although the events were not associated with any symptomatic AEs (investigators were instructed to record all events of extrasystoles as AEs). As the dose of VI is similar in both FF/VI 200/25 and FF/VI 100/25, the reason for this discrepancy is unclear.

Pneumonia was reported by <1% of patients in any of the key treatment groups. Investigators determined the diagnosis of pneumonia and were requested, but not mandated, to provide X-ray confirmation. Of the 40 patients in the key treatment groups who reported a pneumonia event, only 27 patients received a chest X-ray, and pneumonia was confirmed by X-ray in 25 of them (Table 7). The incidence of X-ray confirmed pneumonia was <1% in all the active treatment groups, compared with <0.1% in the placebo group (Table 7). The low number of events in each treatment group may mean any differences are difficult to identify. The exposure-adjusted incidence of X-ray confirmed pneumonia in the FF/VI 200/25 and FF/VI 100/25 groups was 5.2 and 7.2/1000 treatment years, respectively, compared with 4.7 in the placebo group, and 5.9 and 7.2 in the FF 200 and FF 100 groups, respectively (Table 7).

The safety of FF/VI in patients with asthma was evaluated in subpopulations based on age, gender, race, and region. The incidences of AEs in these subgroups were similar to the incidence in the ITT population across the key treatment groups.

The change from baseline in heart rate by treatment group is shown in Fig. 3. The mean baseline heart rates across the six key treatment groups ranged from 69.5 to 72.4 beats per minute. The maximum mean change from baseline at 24-h pre-dose was <1 beat per minute for the FF/VI and placebo groups.

Change from baseline in heart rate at a T max (data from: NCT00600171, NCT01165138 [subset], NCT01134042 [subset], and NCT01018186) and b pre-dose (data from: NCT00600171, NCT01181895, NCT01165138, NCT01134042, NCT01498653, and NCT01498679). FF fluticasone furoate, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, T max time to reach the observed maximum concentration, VI vilanterol

Data from ten clinical studies (n = 2547) were used to assess urine free cortisol excretion (key treatment groups displayed in Table 8). At baseline, the geometric means for 24-h UC excretion ranged from 57.46 to 64.30 nmol/24 h across the five treatment groups. At the end of treatment, the 24-h UC excretion geometric means were numerically similar to baseline.

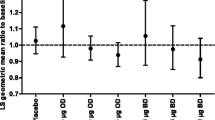

There were no statistically significant differences in the asthma composite endpoint (defined as asthma-related hospitalizations, intubations, or death) analysis of all FF/VI doses versus all ICS doses (i.e., the 95% CIs for the difference all included zero; Fig. 4). The common odds ratio was 0.854 (95% CI 0.344–2.146). Within the subgroup analyses by race and age, there were no differences between all FF/VI and all ICS doses. For African Americans, there was a single composite endpoint event with FF/VI. In adolescents, there were four events in the FF/VI group and two in the ICS group; it is notable that three of the four events on FF/VI occurred at a single site in Eastern Europe, where the site protocol was to hospitalize patients with asthma exacerbations who required treatment with systemic corticosteroids. One patient was hospitalized due to an asthma exacerbation, but did not require treatment with systemic corticosteroids.

Efficacy Analysis

Data for trough and weighted mean FEV1 for the four pivotal studies are shown in Fig. 5. There was a statistically significant difference in trough FEV1 (p < 0.014; Fig. 5a) and 0–24 h weighted mean FEV1 (p < 0.048; Fig. 5b) between the FF/VI and FF treatment groups in all studies, with the exception of NCT01165138. It is notable that in the NCT01165138 study (which investigated FF/VI 100/25, FF 100, and placebo), the weighted mean FEV1 was assessed in just over half (51%) of the population, whereas all patients in the NCT01686633 study (which investigated FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, and FF 100) underwent 24-h serial spirometry. In the NCT01134042 study, FF/VI 200/25 significantly improved trough and weighted mean FEV1, peak expiratory flow, and rescue- and symptom-free 24-h periods compared with FF 200. When rescue- and symptom-free 24-h periods were assessed, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.010) between FF/VI and FF treatment groups was observed in all studies, with the exception of study NCT01165138. The analysis of study NCT01165138 is descriptive only, as the statistical hierarchy stated that a positive outcome must be shown for the primary endpoints of FEV1 to allow interpretation of the secondary endpoints (Fig. 6) [21]. To account for multiplicity across treatment comparisons and key endpoints, a specific step-down testing procedure was applied, whereby inference for a test in the predefined hierarchy was dependent upon statistical significance having been achieved for the previous tests in the hierarchy. For study NCT01165138, statistical significance was achieved at the 5% level for four of the six designated primary comparisons at the top of the hierarchy (FF/VI 100/25 versus placebo and FF 100 versus placebo for the co-primary endpoints of trough FEV1 and weighted mean FEV1), but was not achieved for the primary comparisons of FF/VI 100/25 versus FF 100 for these co-primary endpoints. Statistical significance was not demonstrated by all primary comparisons and no statistical inference could be made on the secondary endpoints (which included rescue- and symptom-free 24-h periods); therefore, these are only descriptive.

Integrated efficacy data were utilized to assess the effects of treatment on trough FEV1 at week 12 in subpopulations. Data from four key efficacy studies (NCT01165138, NCT01134042, NCT01086384, and NCT01686633) were integrated and the treatments were combined regardless of dose, so that treatment with FF/VI could be compared with FF for the subpopulations. Subpopulation analyses of trough FEV1 demonstrated that the treatment effect was directionally similar as in the total ITT population (Fig. 7). The widths of the CIs are a reflection of the sample size.

Benefit:risk Ratio

The benefit:risk ratio of FF/VI 200/25 versus FF/VI 100/25 and FF/VI 100/25 versus FF 100 is shown in Fig. 8. The combination of FF with VI showed increased efficacy compared with FF alone across a range of efficacy endpoints, including lung function, rescue-free 24-h periods, rate of asthma exacerbations, and asthma control [as measured by the Asthma Control Test™ (ACT) (GSK, Brentford, London)]. There was a relatively low incidence of drug-related AEs with FF/VI (6% for both doses) compared with 2% for placebo; no event occurred in >2% of patients at either dose of FF/VI, showing that the combination is associated with a low risk of events. As shown in Fig. 2b, there were no relevant differences with the addition of VI to FF on the incidence of asthma events and other safety outcomes. In the clinical setting, having an alternative dose of an ICS allows treatment to be modified with differences in disease severity. This ability to adjust the corticosteroid dose is in agreement with treatment guidelines for the ICS/LABA combination products. Comparing the efficacy of FF/VI 200/25 with FF/VI 100/25, there was a numerical benefit with the higher strength versus the lower strength on several efficacy variables, including lung function, rescue-free 24-h periods, and asthma control (as measured by ACT). As also shown, comparison of the safety profile of FF/VI 200/25 versus FF/VI 100/25 supports the positive benefit:risk ratio of FF/VI 200/25, as we did not observe any relevant increases in AEs with the higher strength; these include SAEs and other potential ICS-related effects. The efficacy and safety of FF/VI shows an overall positive benefit:risk profile for the combination therapy.

Summary of benefit:risk ratios for a FF/VI 100/25 versus FF/VI 200/25, b FF 100 versus FF/VI 100/25, c ICS versus FF/VI. ACT Asthma Control Test™, AE adverse event, CI confidence interval, FEV 1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, FF fluticasone furoate, ICS inhaled corticosteroid, VI vilanterol, WM weighted mean

Discussion

The integrated safety analyses presented here provide evidence that FF/VI administered as a maintenance therapy has a favorable safety profile in patients with asthma. No drug-related AEs or safety signals were identified from these integrated analyses that were not already established as known class effects of ICS/LABA combination therapy and included in the labeling information for FF/VI. Findings from the efficacy analyses demonstrate that the once-daily combination of FF/VI improves lung function and symptomatic endpoints at both approved doses.

Some potential pharmacological class risks have been associated with ICSs and LABAs. In these integrated analyses, an increased incidence of oropharyngeal pain, dysphonia, oral candidiasis, and oropharyngeal candidiasis was observed in the FF-containing key treatment groups compared with the placebo group. These effects are known potential risks associated with ICS use and are included in the label for FF/VI. A numerically higher exposure-adjusted incidence of local steroid effects, cardiovascular effects, and hypersensitivity reactions was observed in the FF/VI 200/25 group compared with the FF/VI 100/25 group. It is unclear why there was a numerically higher exposure-adjusted incidence of cardiovascular events in FF/VI 200/25 compared with FF/VI 100/25, as the same dose of the LABA (VI) is included in both strengths. Cardiovascular events were reported by 4–5% of patients receiving FF/VI compared with 3% or less in any of the other key treatment groups. It is notable that Holter monitoring was only carried out in the long-term safety study [31], and this was the only study to include FF/VI 200/25, FF/VI 100/25, and twice-daily FP 500. The low incidences of X-ray confirmed pneumonia observed across all key treatment groups are consistent with the background rate in the asthma population, and for FF/VI 200/25, the exposure-adjusted rates are similar to the exposure-adjusted rates of pneumonia that were reported for placebo, FP, and budesonide in a meta-analysis of data from budesonide studies [33].

The use of LABA monotherapy in asthma has been associated with potential increased risk of serious asthma-related outcomes [34], although the same concern has not been shown with ICS/LABA combination therapies [35]. Assessment of the asthma composite endpoint, comprising asthma-related hospitalizations, intubations, or deaths, may help to indicate the risk of asthma-related deaths with LABA treatment. There were no differences in the asthma composite endpoint between the FF/VI treatment groups and the ICS or non-LABA group. This demonstrated that the addition of VI, a LABA, was not associated with any increase in the frequency of asthma-related events requiring hospitalization. The risk difference for patients receiving FF/VI versus patients receiving ICSs alone was −0.02%, which represents two fewer hospitalizations per 10,000 patients with FF/VI versus ICSs alone. These data suggest the risk of asthma-related events does not increase when VI is used concurrently with FF.

It is evident that the combination of FF with VI increases treatment efficacy compared with FF alone, as demonstrated by the improvement in lung function and increase in rescue-free 24-h periods (improvement in lung function is expected with the addition of a LABA). The higher dose of FF/VI, 200/25, appears to provide some numerical benefit over FF/VI 100/25 on several efficacy variables with no additional safety risk to patients.

This integrated analysis was performed on a large patient database (>7000 patients), with 46% of these patients receiving the approved dose of FF/VI (i.e., 200/25 or 100/25 µg), and consisted of a rigorous assessment of pharmacologically predictable effects, such as cortisol suppression and effects on heart rate, and independent adjudication for the asthma composite endpoint. One limitation of this analysis is that there were differences between the studies in the populations, treatments, and treatment durations, which precluded the integration of efficacy endpoints other than FEV1, at week 12, such as rescue-free days and withdrawals. The difference in treatment durations also limits the interpretation of long-term effects, as the longest duration of treatment with placebo was 24 weeks compared with 76 weeks for FF/VI and FF. In the subgroup analysis by race and age, some treatment groups were small in size.

Conclusion

In this integrated analysis, there was no evidence of an increased safety risk associated with FF/VI compared with FF or placebo. These data support the positive benefit:risk ratio of FF/VI compared with FF alone. The availability of two approved strengths of FF/VI offers flexible treatment options for patients with differing disease severity, and the single dosing of FF/VI may improve treatment adherence.

References

Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global burden of asthma. 2015. http://www.ginasthma.org/. Accessed Nov 2015.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH). National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. 2007. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf. Accessed Nov 2015.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128.

Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14009. doi:10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.9.

Lindsay JT, Heaney LG. Non-adherence in difficult asthma and advances in detection. Exp Rev Resp Med. 2013;7(6):607–14.

Cooper V, Metcalf L, Versnel J, Upton J, Walker S, Horne R. Patient-reported side effects, concerns and adherence to corticosteroid treatment for asthma, and comparison with physician estimates of side-effect prevalence: a UK-wide, cross-sectional study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:15026.

Wu AC, Bulter MG, Li L, et al. Primary adherence to controller medications for asthma is poor. Ann Am Thoracic Soc. 2015;12(2):161–6.

Levy ML, Andrews R, Buckingham R, et al. Why asthma still kills: The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD). Royal College of Physicians. May 2014. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills. Accessed Nov 2015.

Mäkelä MJ, Backer V, Hedegaard M, Larsson K. Adherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(10):1481–90.

Wells KE, Peterson EL, Ahmedani BK, Williams LK. Real-world effects of once vs greater daily inhaled corticosteroid dosing on medication adherence. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(3):216–20.

GlaxoSmithKline. BREO ELLIPTA US prescribing information. https://www.gsksource.com/pharma/content/dam/GlaxoSmithKline/US/en/Prescribing_Information/Breo_Ellipta/pdf/BREO-ELLIPTA-PI-MG.PDF. Accessed Sept 2015.

GlaxoSmithKline. RELVAR ELLIPTA EU prescribing information. https://hcp.gsk.co.uk/products/relvar/prescribing-information.html. Accessed Sept 2015.

GlaxoSmithKline. RELVAR ELLIPTA EU summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002673/WC500157633.pdf. Accessed Aug 2015.

GlaxoSmithKline. REVINTY ELLIPTA EU summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002745/WC500168853.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016.

GlaxoSmithKline. RELVAR ELLIPTA Japanese Drug Information. http://glaxosmithkline.co.jp/healthcare/. Accessed Feb 2016.

Busse WW, Bleecker ER, Bateman ED, et al. Fluticasone furoate demonstrates efficacy in patients with asthma symptomatic on medium doses of inhaled corticosteroid therapy: an 8-week, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Thorax. 2012;67(1):35–41.

Bleecker ER, Bateman ED, Busse WW, et al. Once-daily fluticasone furoate is efficacious in patients with symptomatic asthma on low-dose inhaled corticosteroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(5):353–8.

Bateman ED, Bleecker ER, Lötvall J, et al. Dose effect of once-daily fluticasone furoate in persistent asthma: a randomized trial. Respir Med. 2012;106(5):642–50.

Lötvall J, Bateman ED, Bleecker ER, et al. 24-h duration of the novel LABA vilanterol trifenatate in asthma patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(3):570–9.

Bleecker ER, Lötvall J, O’Byrne PM, et al. Fluticasone furoate-vilanterol 100-25 mcg compared with fluticasone furoate 100 mcg in asthma: a randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(5):553–61.

O’Byrne PM, Bleecker ER, Bateman ED, et al. Once-daily fluticasone furoate alone or combined with vilanterol in persistent asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(3):773–82.

Bernstein DI, Bateman ED, Woodcock A, et al. Fluticasone furoate (FF)/vilanterol (100/25 mcg or 200/25 mcg) or FF (100 mcg) in persistent asthma. J Asthma. 2015;52(10):1073–83.

Bateman ED, O’Byrne PM, Busse WW, et al. Once-daily fluticasone furoate (FF)/vilanterol reduces risk of severe exacerbations in asthma versus FF alone. Thorax. 2014;69(4):312–9.

Lin J, Kang J, Lee SH, et al. Fluticasone furoate/vilanterol 200/25mcg in Asian asthma patients: a randomized trial. Respir Med. 2015;109(1):44–53.

Woodcock A, Lötvall J, Busse WW, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluticasone furoate 100 µg and 200 µg once daily in the treatment of moderate-severe asthma in adults and adolescents: a 24-week randomised study. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:113.

O’Byrne PM, Woodcock A, Bleecker ER, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily fluticasone furoate 50 mcg in adults with persistent asthma: a 12-week randomized trial. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):88.

Busse W, Bateman E, O’Byrne P, et al. Once-daily fluticasone furoate 50mcg in mild to moderate asthma: a 24-week placebo-controlled randomized trial. Allergy. 2014;69(11):1522–30.

Lötvall J, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluticasone furoate 100 µg once-daily in patients with persistent asthma: a 24-week placebo and active-controlled randomised trial. Respir Med. 2014;108(1):41–9.

Woodcock A, Bleecker ER, Lötvall J, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluticasone furoate/vilanterol compared with fluticasone propionate/salmeterol combination in adult and adolescent patients with persistent asthma: a randomized trial. Chest. 2013;144(4):1222–9.

Lötvall J, Bateman ED, Busse WW, et al. Comparison of vilanterol, a novel long-acting beta2 agonist, with placebo and a salmeterol reference arm in asthma uncontrolled by inhaled corticosteroids. J Negat Results Biomed. 2014;13(1):9.

Busse WW, O’Byrne PM, Bleecker ER, et al. Safety and tolerability of the novel inhaled corticosteroid fluticasone furoate in combination with the β2 agonist vilanterol administered once daily for 52 weeks in patients ≥12 years old with asthma: a randomised trial. Thorax. 2013;68(6):513–20.

Allen A, Schenkenberger I, Trivedi R, et al. Inhaled fluticasone furoate/vilanterol does not affect hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in adolescent and adult asthma: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Respir J. 2013;7(4):397–406.

O’Byrne PM, Pedersen S, Carlsson LG, et al. Risks of pneumonia in patients with asthma taking inhaled corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(5):589–95.

Levenson M. Long-acting beta-agonists and adverse asthma events meta-analysis: statistical briefing package for joint meeting of the Pulmonary–Allergy Drugs Advisory Committee, Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee, and Pediatric Advisory Committee on December 10–11, 2008. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/briefing/2008-4398b1-01-FDA.pdf. Accessed Feb 2016.

Bateman E, Nelson H, Bousquet J, et al. Meta-analysis: effects of adding salmeterol to inhaled corticosteroids on serious asthma-related events. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:33–42.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were funded by GSK. All studies were funded by GSK (NCT01165138, NCT01134042, NCT01686633, NCT01086384, NCT01498653, NCT01498679, NCT01147848, NCT00603746, NCT00603278, NCT00603382, NCT01436071, NCT01436110, NCT01159912, NCT01431950, NCT00600171, NCT01181895, NCT01018186, and NCT01086410). The authors would like to express thanks to all participating patients, investigators, and technicians involved in these studies. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval of the version to be published. Editorial support in the form of development of the draft outline and manuscript first draft in consultation with the authors, editorial suggestions to draft versions of this paper, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, referencing, and graphic services was provided by Katherine St John, Ph.D. at Gardiner-Caldwell Communications (Macclesfield, UK), and was funded by GSK.

Disclosures

WB reports personal fees from Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Roche, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Teva, Aerocrine, Boston Scientific, Circassia, and ICON. LA, LF, CH, and LJ are all employed by GSK and all hold GSK stocks/shares.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. All studies complied with the principles of Good Clinical Practice (International Conference on Harmonisation, 1996) and were approved by relevant Ethics Committees/Institutional Review Boards. Informed consent was obtained. The studies were performed in accordance with the applicable version of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013) at the time the studies were conducted. Regulatory approval was obtained from the relevant health authority where required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/94C4F06042C0D1C9.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Busse, W.W., Andersen, L., Frith, L. et al. An Integrated Analysis of Fluticasone Furoate/Vilanterol (FF/VI) Versus FF Safety Data Across Phase II and III Asthma Studies. Pulm Ther 2, 91–114 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-016-0015-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41030-016-0015-1