Abstract

Eight sister North-East states of India are unique in diverse flora and fauna and manifest distinctive social and ethnocultural identities. Meanwhile, North-East states exhibit common problems ranging from ethnic conflict, insurgency, and secessionist movement, illegal taxing and extortion, and drug trafficking to poor transportation and communication and immigration issues. The region incurs prolonged ethnopolitical turmoil, which left imprints on the migration from this region. The present study examines the level, trend, and pattern of interstate migration from the North-East during 1991–2011 and associates it with prolonged ethnopolitical turmoil. The exodus of workers to the mainland Indian states implies a lack of employment opportunities. Employment elasticity suggests that income growth in North-East states lacks inclusiveness and fails to sensitise the employment opportunities, inducing the workers to migrate from North-East into mainland Indian states. Not only the labour migration but the student migration is also conspicuous, which exhibits the weakness of the educational system. The decades-long ethnopolitical unrest and enforcement of AFSPA of 1958 for more than 60 years caused predicaments of economic developments, employment opportunities, and challenge to the fundamental human rights and social well-being, resulting in people being forced to move out in the 1990s and 2000s.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Migration is an indicator that implies socio-economic changes in an area or region. In the 2011 Census, more than one-third of Indians, 37.6 per cent or 455.8 million, reported as lifetime migrants—four out of every ten Indian are migrants. The proportion increased from 31 per cent or 314.5 million, with a growth rate of 4.5 per cent per annum between 2001 and 2011. When the total volume of migrants is quite large, interstate migrants are minuscule and have been surprisingly low since 1961. It was recorded 3.3, 3.4, 3.6, 3.3, and 4.1 per cent in 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, and 2001, respectively, and finally reached 4.5 per cent or 54.3 million in 2011 (Das and Mistri 2015).

As the cheap labour force is one of the important factors of production, interstate labour migration balances the demand of labour to the economically well-off states like Maharashtra, Gujrat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Delhi, Punjab, and Haryana, supplying from the economically less-progressive states, namely Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, and Rajasthan. This trend has remained the same since the 1991 Census (Mistri 2021). In the 2011 Census, the North-East States and even West Bengal contributed substantially to the labour force supply (Mistri 2021). Despite a very meagre proportion, interstate migration plays a significant role in India's economic growth, and it shows unique characteristics for North-East states. The present study mainly focuses on migration from North-East states during 1991–2011 and its association with decades-long ethnopolitical turmoil.

2 North-East as an Ethnopolitical Disturbed Frontier

North-East India comprises eight sister states—Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura, and Sikkim. It was politically recognised in 1972 when North Eastern Council (NEC) was formed by the North Eastern Council Act of 1971. Being a frontier region, North-East is geostrategically significant and a potential corridor for trading with the vibrant economic zone of South and South-East Asia. The region incurs a distinctive social and cultural identity. The multi-ethnic demographical composition of the indigenous peoples manifests a unique culture, language and religious profiles, which are not found in any other region of India.

Meanwhile, North-East counters common problems ranging from poor transportation and communication, ethnic conflict and insurgency, illegal taxing and extortion, and drug trafficking to immigration issues. The ethnic-based conflicts often backed by underground organisations are still alive and mobile. Nowadays, ethnic movements in North-East have deviated from the traditional socio-cultural roots to ethnopolitical aspirations. A populist political aspiration, ‘self-determination’ has been witnessed in North-East politics (Shimray 2004). The demand for a Greater Nagaland (Nagalim), along with a separate constitution and flag consolidation of the Naga-inhabited areas of neighbouring Assam, Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh, and border areas of Myanmar, creates widespread discontent among the North-East states. The ethnic consciousness in the region entices ‘identity expansion’ by merging, either voluntarily or forcefully, several smaller groups together (Shimray 2004). More than 40 odd ethnic groups combined emergence as great Nagas. Mizos include various clans, such as the Hmar, Ralte, Lai, Lusei, etc. Haokip, Kipgen, and other Thadou speaking groups together form Kuki Groups. The nomenclature, Zomi, is adopted by Zous, Simtes, Vaipheis, Paites, Raltes, Suhtes, Gangte, and Tedim-Chin ethnic groups (Kipgen 2013; Shimray 2004). Demographic power strengthens the ethnopolitical movements and leads to ethnic hegemony of the majority over the minority, resulting in ethnic conflict. Kuki-Naga clash and Kuki-Zomi violence in the 1990s in Manipur and surroundings are notable instances (Brahmachari 2019; Hoenig and Kokho 2018; Haokip 2015; Shimray, 2004; 2001). Indeed, the ethnopolitical issue has been the internal security concern of India as a nation. More than 60 years of implementation Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) of 1958 has failed to tackle the problem (Yumnam 2018), and reassessment is an urgent need.

Economic development and social well-being are embedded in a peaceful environment (Aisen and Veiga 2013; Fosu 2001; Feng 1997; Alesina et al. 1996). Migration acts as a barometer that infers the socio-political and economic changes in a region. Conflict, insurgency and political instability are used to leave an imprint on the processes of migration. More than one million North-East people, around two per cent of interstate migrants in India, were recorded as interstate migrants in each of the 2001 and 2011 Census. The highest proportion of Scheduled Tribes (STs) lives in the North-East States. Indigenous people hardly leave their territory for livelihood purposes (GOI 2018). Around 0.75 and 0.54 million North-East people migrated to mainland Indian states in 2001 and 2011. Almost 30 per cent migrated in search of work. In addition, student migration from North-East in a large volume is conspicuous. A substantial proportion of 13 per cent also migrated for ‘others’ reasons, such as seeking to avoid or escape conflict, political unrest, and natural calamities.

3 Objectives of the Study

The focal point of the present study is migration from North-East India during 1991–2011, and its association with prolonged ethnopolitical turmoil in the region. The study discusses the level, trend, pattern, and processes of interstate migration from the North-East. State-specific net balances of migration are estimated to examine the moving in- and out-migrants from the region. The exodus of North-Eastern workers to mainland Indian states implies a lack of employment opportunities. Employment opportunities are inextricably linked with economic growth, considered a prerequisite for growing employment (ILO 2018). Hence, employment and economic growth in the North-East states are investigated with empirical rigour. In this backdrop, employment elasticity for North-East states during 1991–2011 is estimated to relate the migration due to work/employment with economic growth in the region.

4 Data Sources

Population Census of 1991, 2001, and 2011 are consulted to discuss the migration scenario during 1991–2011. Census reference Table-D contains the data of migration. The periodic employment and unemployment data are compiled from the various rounds,1993-94, 1999-00, 2004-05, 2007-08, 2009-10, and 2011-12 of the National Sample Survey (NSS), and Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017-18 conducted by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) under the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MOSPI). The data on economic growth are collected from the Handbook of Statistics on Indian States by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and erstwhile the Planning Commission of India, now NITI Aayog.

5 Method

Various measures of migration, descriptive statistics, and cartographic techniques are incorporated to analyse and represent the data sets. Employment elasticity for the North-East States estimates the ability of the economy to generate employment opportunities for its population. Employment elasticity is a convenient way of summarising the sensitivity of employment to income growth (Misra and Suresh 2014; Kapsos 2005). The ‘arc’ elasticity with the ‘Compound Annual Growth Rate’ (CAGR) approach (Misra and Suresh 2014) is adopted in the study; the formula is as follows.

6 Operational Definitions

Census of India collects information on migration based on two aspects—migration by ‘place of birth’ (POB) and ‘place of last residence’ (POLR). A person would be considered a migrant by POLR if she/he had last resided at a place other than her/his place of enumeration. Migration by POLR during 1991–2011 is considered in the present study. Census of India has produced the data (table D-3) on migration by POLR into certain ‘fixed-term’ or ‘period migration’ based on the duration of stay in village/town since migration, such as duration less than 1 year, 1–4 years, 5–9 years, 10–19 years, 20 years and above, and duration not stated. Migrants who had migrated within 0–9 years are called ‘intercensal migrants’ (Mistri 2021; Lusome and Bhagat 2006). In the present study, ‘intercensal migration’ (0–9 years) is computed by adding up less than 1 year, 1–4 years, and 5–9 years duration of staying. In addition, migration of all durations is defined as ‘lifetime migration’ as the migration time is unknown (Lusome and Bhagat 2006). Further, employment elasticity measures the change in employment with a one percentage point change in the economic growth (Misra and Suresh 2014; Kapsos 2005).

The study is divided into three sections. Section A deals with migration processes, which include volumes of migration, streams and places of destinations, and net balances of intercensal migration. Section B focuses on push factors of migration, such as various reasons directly captured in the population Censuses, unemployment rate, and employment elasticity. Finally, a critical discussion and conclusion are drawn in Section C.

7 Section A: Processes of Migration

A migration process comprises a wide range of migration aspects, such as level, trend and rate of migration, its balance over the periods, who migrates and from where, where they are going, changing macro-patterns, and so.

7.1 Interstate Migration Stock

According to the migration by POLR, a total of 1.03 million migrants, that is 2.24 per cent of North-East’s 45.8 million population and 1.89 per cent of the country’s 54.3 million interstate migrants, reported as interstate (lifetime) out-migrants in the 2011 Census (Table 1). The previous 1991 and 2001 Census had recorded 0.65 million or 2.04 per cent of North-East’s population and 1.11 million or 2.86 per cent interstate out-migrants, respectively. Lifetime migrants increased in 2001, but again declined in 2011. Likewise, the share of intercensal (0–9 years) migrants increased to 1.18 per cent in 2001 from 0.92 per cent in 1991 but slightly dropped to 1.03 per cent in 2011 (Table 1). The observed growth of interstate migration is 56.2 per cent during 1991–2001 and drastically declines to 3.2 per cent during 2001–2011.

Among the North-East states, Assam always contributed the highest, 58.8, 61.4, and 64.5 per cent (intercensal migrants) in 1991, 2001, and 2011, respectively, that is, on average, 60 per cent of the interstate out-migrants (Table 1). In contrast, none of the North-East States shares more than 7.0 per cent. In Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, and Meghalaya, the growth rates of intercensal migrants have turned positive in the 2000s from negative ones in the 1990s. Nagaland and Mizoram witnessed an unprecedented expansion of out-migrants, 306.5 and 168.2 per cent, respectively, in the 1990s, while, in the 2000s, out-migration from these has declined drastically. This appears to reflect a strong connection between ethnic conflict and migration.

7.2 Migration to Mainland India

In the 2011 Census, 0.54 million or 52.7 per cent out of 1.03 million total lifetime migrants moved to the mainland Indian states (Table 2). In 2001, it was recorded 0.75 million or 67.9 per cent out of 1.11 million lifetime migrants. Likewise, intercensal North-East migrants in mainland India declined to 56.9 per cent (0.27 million) in 2011 from 62.5 per cent (0.29 million) in 2001. The growth of North-East migrants in the mainland has fallen at 6.0 per cent during 2001–2011. While most migrants in Sikkim and Assam prefer to migrate to the mainland, migrants in the rest of the six states witnessed the retention within the North-East. Except for Sikkim and Mizoram, all the North-East States have experienced a declining share of migration in mainland India in 2011 (Table 2).

7.3 Place of Destinations

Most of the interstate migrations occur between neighbouring states those are close to each other in geographic proximity. In 2011, almost half of the intercensal migrants from Sikkim preferred to migrate to West Bengal. A substantial proportion of migrants from Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Meghalaya, liked to move to Assam, 46.2, 45.8, and 47.8 per cent, respectively. Likewise, migrants from Tripura prefer Assam (31.4 per cent) and West Bengal (20.0 per cent). Assamese prefer to migrate to four neighbouring states, namely WB (15.1 per cent), Arunachal Pradesh (13.9 per cent), Nagaland (8.2 per cent), and Meghalaya (7.7 per cent).

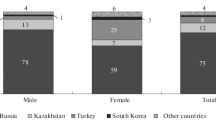

Irrespective of individual preference, people from the North-East prefer to migrate to West Bengal. West Bengal shared 13.4 and 13.8 per cent in the 2001 and 2011 Census, respectively. Other predominant destinations in mainland India are Delhi, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar (Fig. 1). A fair proportion of North-East migrants are also recorded in Haryana and Punjab. During the intercensal period, north-East migrants in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi have dropped drastically. North-East migrant in Bihar was recorded 13.4 per cent in 2001, but it drastically reduced to 1.4 per cent in 2011; it is nearly 12 per cent point downfall during 2001–2011 (Census, 2011; 2001). Likewise, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi have been recorded an almost 5.0 and 2.0 per cent point (respectively) decline of North-East migrants from 2001 to 2011 (Census, 2011; 2001). Two South Indian States, namely Karnataka and Maharashtra, have been gaining the ground of North-East migrants during the intercensal period. Another two Southern States, such as Kerala and Tamil, have emerged as new destinations for North-East migrants in the 2011 Census. A changing pattern of migration flow to the mainland states is observed—while the overall volume of North-East people migrating to the North and East Indian states has declined during 2001–2011, the Southern states have been accounted increasing of the same.

Source: Computed from Census of India, 2011

Flow of migrants from North-East to Mainland States/UTs, 2011 Census.

7.4 Migration from Mainland to the North-East

According to the 2011 Census, around 0.57 million or 54.1 per cent out of 1.06 million total lifetime in-migrants in the North-East came from mainland Indian states. In 2001, it accounted for about 0.51 million or 58.8 per cent out of a total 0.87 million in-migrants. Therefore, interstate lifetime migrants from mainland Indian States have slightly declined from 59 to 54.1 per cent between 2001 and 2011. Meanwhile, the share of intercensal in-migration remained the same, 51.0 and 50.8 per cent in 2001 and 2011, respectively.

Considering the data on state-specific intercensal migration, around 43 per cent of the total migrants came from six mainland states, namely West Bengal (18.7 per cent), Bihar (12.3 per cent), Jharkhand (4.4 per cent), Uttar Pradesh (4.3 per cent), Rajasthan (2.6 per cent) and Odisha (1.0 per cent). Bihar contributed 17.0 and 19.0 per cent in the 2001 and 2011 Census, respectively, followed by West Bengal, 13.0 and 12.3 per cent in 2001 and 2011. Migration flow from the states mentioned above, excluding Bihar and Jharkhand which have witnessed an increasing trend, has declined during 2001–2011.

There is a wide contention that in-migration or immigration to the North-East region is perceived as threatening to indigenous people. The fear of assimilation and diffusion begets the syndrome of xenophobia among the indigenous population in the North-East (Shimray 2004). Earlier, colonial regulations like the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation (BEFR) of 1873, and its later extension, the Inner Line Permit (ILP) system in the post-independence period, have been one of the safeguards on the policy front. Since the 1990s, the North-East has been confronted with further challenges in the trade-off between economic development and traditional economic and socio-cultural systems due to India’s economic liberalisation and the effects of globalisation (Yumnam 2018). Outsiders, either in the form of interstate migration or immigration, enter into the North-East, fuelling social unrest against them, contributing to the North-East's image as an anti-migration region.

7.5 Net Balance of Migration

The migration balance is the difference between the number of migrants entering and leaving an area in a certain period. If the net migration becomes negative, it infers that people are leaving the area through out-migration. The positive net migration suggests the population gaining through in-migration. According to the intercensal (0–9 years) migration, the North-East region has witnessed a negative balance of migration, − 69,476 and − 15,865 in the 2001 and 2011 Census, respectively (Table 3). The rate of migration has declined to − 0.04 per cent during 2001–2011 from − 0.22 per cent during 1991–2001. Though the negative balance of migration has reduced around four folds from the 2001 to 2011 Census, it is still negative. It suggests that more people are still leaving the North-East region than migrating into it.

Manipur and Assam experienced negative migration balance in the 2011 Census; these had also witnessed negative in 2001. Nagaland (− 1.37 per cent) and Mizoram (− 0.10 per cent) had witnessed negative net migration in 2001, but these turned into a substantial positive in 2011.

8 Section B: Thrust of Migration

8.1 Reasons for Migration

The Census of India collects information on reasons for migration in seven categories: work/employment, business, education, marriage, moved after birth, moved with household, and others. The category ‘natural calamities’ as one of the reasons for migration was excluded, and a new reason ‘moved at birth’ was added in the 2001 Census.

Table 4 shows the reason for (intercensal) migration, ‘family moved/moved with household’ was recorded highest share over the census periods, 36.5, 30.3 and 29.3 per cent in 1991, 2001, and 2011, respectively. It is followed by marriage and work/employment. ‘Moved with household’ is the association migration or family unification, as in due course of time, the entire dependent family members unite with the migrant at the new place.

In India, there is a wide gender difference in the reasons for migration, especially for work/employment and marriage. Interstate migration is female-dominated. The share of interstate lifetime migrants for females was recorded- 55.5, 53.6, and 56.0 per cent in the 1991, 2001, and 2011 Census, respectively. More than half of females migrate due to marriage. In contrast, interstate male migration is attributed to work/employment. Interstate lifetime male migration due to work/employment was reported- 43.4, 52.2, and 47.2 per cent in the 1991, 2001, and 2011 Census, respectively. The North-East states are not an exception. The intercensal male migration for work/employment was recorded 31.9, 38.0, and 46.9 per cent in 1991, 2001, and 2011, which is observed an increasing trend. In India, interstate educational migration is always low, 3.5, 2.6, and 2.5 per cent in 1991, 2001, and 2011, respectively. But the North-East states witnessed almost double, 6.1, 5.8, and 6.9 per cent in 1991, 2001, and 2011, respectively (Table 4), compared to all India average. Migration due to ‘business’ has twofold declined between 1991 and 2001 and this trend is continuing in 2011.

Those who are not covered above-mentioned six reasons for migration are categorised as migration for ‘other’ reasons. Significantly, a large proportion of North-East people reported the cause of migration, ‘other’, 13.5, 15.2, and 13.0 per cent, respectively, in 1991 and 2001 and 2011 (Table 4), which are higher than all India average, 11.0, 8.4, and 11.3 per cent, respectively. It has been mentioned at the beginning that the category ‘natural calamities’ was omitted in the 2001 Census. When ‘natural calamities’ are excluded from the primary category, it is automatically merged with reason, ‘other’, which includes natural calamities or hazards and socio-economic and political stressors, such as riots, conflict, and political unrest.

North-East is affected by three major natural stressors: floods, earthquakes, and landslides. The whole North-East region, excluding Sikkim, is included in the seismic zone V, a very severe intensity zone. The low-intensity tremors are quite frequent in the North-East. Since the mid-nineteenth century, North-East has witnessed seven earthquakes with an intensity of more than 7.0 on the Richter scale, of which two (in 1897 and 1950) occurred during the last hundred years (Dikshit and Dikshit 2014). These were measured 8.7 and 8.5 on the Richter scale, respectively. The earthquake of 1950 was triggered a colossal loss of property and life and changed the course of rivers (Dikshit and Dikshit 2014). Flood is very common in Assam in every monsoon caused by the mighty Brahmaputra. Another river is the Barak flows through Manipur, Mizoram, and Assam. During 1953–1995, a total of 98.10 million people was affected by flood in Assam itself (Dikshit and Dikshit 2014, p. 181). The most landslide-prone states are Mizoram, Manipur, and Arunachal Pradesh. Frequent tremors and heavy rainfall lead to landslides with various scales from large to small intensity.

Earthquakes and landslides do not force the people to move long-distance, relatively locally displaced (Perch-Nielsen 2004; Belcher and Bates 1983). Even people return to their original places after the water goes down in case of a flood (Mistri 2019; Banerjee et al. 2011). In the Indian context, natural calamities either cause displacement locally or migration within the state boundary but hardly cause interstate migration (Mistri and Das 2020). It is observed that natural calamities induced 25,107 interstate migrants in North-East states during 1981–1991 (Census 1991). The share is pretty small, 0.9 per cent to total interstate migrants in North-East in the 1991 Census (Table 4), whereas all-India share is 0.4 per cent. Meanwhile, the reason for migration, ‘other’ accounted for around 17 per cent of interstate migrants in the same Census, 1991. Therefore, the reason for migration, ‘natural calamities’, which fall in the category, ‘other’, hardly contribute to a large. In the North-East context, the reason for migration, ‘other’ reflects socio-political factors underlying migration. The prolonged ethnopolitical turmoil caused predicaments of economic development, employment opportunities, and challenge to social well-being resulting in people being forced to move out.

8.2 Reasons for Migration to the Mainland States

In the 2011 Census, on average, 30 per cent of North-East migrants reported work/employment as the reason for migration to mainland states, which accounted for around 17.0 per cent in 2001 and increased by 13.0 per cent point during 2001–2011 (Table 5). Nearly one-third (32.1 per cent) of intercensal migrants from Assam and one-fourth from Manipur (29.0 per cent), Mizoram (26.0 per cent), and Nagaland (25.0 per cent) migrated for work/employment in 2011. Student migrants in the mainland in 2011 were recorded as 9.0 per cent, which increased from 7.0 per cent in 2001. The students mostly prefer to go to cities like Bengaluru and Delhi (Marchang 2017; McDuie-Ra 2014; 2012), and to some extent, to Mumbai and Kolkata. Except for Assam, all the North-East states witnessed substantially higher student migration to mainland India. Manipur ranked top, which shared 29 per cent in 2011, though it had stepped down from 37.3 per cent in 2001, followed by Mizoram (25.0 per cent) and Arunachal Pradesh (23.3 per cent). Assam, especially Guwahati, is educationally and culturally endowed since the colonial period. Post-independent period, many central and state-funded universities, IIT, NIT, and research institutions have been set up; these helped retain the students and also attract others from neighbouring states.

The reason, ‘other’, which includes forced migrants, increased to 13.0 per cent in 2011 from 10.2 per cent in 2001. Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh witnessed the highest addition in interstate migrants, 7.0 and 6.0 per cent points, respectively, between 2001 and 2011. Migration for ‘business’ to mainland states from Tripura was recorded, 3.6 per cent, a bit higher than the rest of the North-East states.

8.3 Unemployment Rate

Since the 1990s, the unemployment rate of the North-East, both in rural and urban areas, strode up (Fig. 2). The urban unemployment rate on usual status (principal status + subsidiary status) jumped to 6.2 per cent in 1999–2000 from 4.5 per cent in 1993–1994 and shot up to 10.2 per cent in 2007–2008.

At the far end of the 2000s, it declined to 6.8 per cent in 2009–2010, but again bounced to 9.6 per cent in 2011–2012 and finally reached 10.5 per cent in 2017–2018. Likewise, the rural unemployment rate in the North-East States has steadily worsened and doubled in every decade since 1993–1994. In 2017–2018, the rural unemployment rate reached 7.9 per cent. The urban–rural difference was around 3.0 per cent in 2017–2018. At the beginning of the 1900s, the urban and rural unemployment rate in North-East was more or less equal to the Indian average. Since the end of the 1990s, these surpassed the Indian average, and the gaps have started widening in the 2000s and 2010s.

The state-specific unemployment rate (Table 6) reveals that Nagaland has caught severe unemployment since the end of the 2000s. According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2017–2018, Nagaland ranked top among the Indian State/UTs (NSO, 2019). The state's estimated total unemployment rate was 21.8 per cent, followed by Manipur (11.6 per cent) and Mizoram (10.1 per cent). In the 2000s, the highest unemployment rate in North-East was observed in Tripura, 13.3 and 28.0 per cent in rural and urban areas, respectively, in 2004–2005, but, later, it has started to decline. Manipur has witnessed a consistently high unemployment rate, especially in urban areas, during the last three decades. According to the 2011 Census, nearly 82 per cent of people lived in rural areas in North-East states. Meanwhile, the rate of urbanisation is also very high, 37.5 per cent during 2001–2011. Hence, growing unemployment, both in urban and rural areas, leads to interstate migration to urban centres elsewhere in India.

8.4 Employment Elasticity of Economic Growth

Employment is one of the essential components of the growth and development process of an economy; it links economic growth and poverty elimination. Thus, employment opportunities are considered a way of attaining inclusive growth and sustainable development in a region or a country. When the lack of job opportunities is inducing a considerable volume of migration from the North-East, it is essential to provide insight into the economic growth and its ability to generate employment opportunities for its population. The employment elasticity of economic growth serves the purpose best. Employment elasticity refers to the percentage change in employment associated with a one percentage change in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or economic growth (Misra and Suresh 2014; Kapsos 2005). In the study, the employment elasticity of North-East states is computed for the 1900s and 2000s.

The average annual growth rate (AAGR) of per capita Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) in the North-East (excluding Mizoram) had retained at 2.7 per cent from 1993–1994 to 1999–2000 (Table 7). Later, it increased to 4.9 per cent during 2001–2004 to 7.1 per cent during 2004–2009. The AAGR for the 2000s is estimated at 6.3 per cent, which is higher than the Indian average of 5.9 per cent. All the states, except Manipur, have experienced economic growth in the 1990s and 2000s.

The ‘arc’ elasticity based on the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) approach unveils that there has been a continuous decline in employment elasticity since 1993–1994 in the North-East region (Table 8). During 1993–1994 to 1999–2000, employment elasticity in North-East (excluding Mizoram) is estimated at 0.81 and has declined significantly to 0.05 in the second half of the 2000s. In the first half of the 2000s, the employment rate is elasticFootnote 1 for Arunachal Pradesh (2.16), Assam (1.21) and Manipur (2.01), and almost unitaryFootnote 2 elastic for Meghalaya (0.99) in response to the per capita NSDP growth, but in the latter half, they have slipped significantly. Though all the financial years' income statistics are not available, Nagaland has performed the worst in employment elasticity among the North-East states. Despite the world economic crisis in 2007–2008, North-East states as a whole had maintained an average of 7.8 per cent per capita economic growth (CAGR) in the second half of the 2000s (Table 8). But none of the North-East states has shown an improvement in employment elasticity. The growth output has not able to sensitise employment in North-East India.

The indicator of employment elasticity not only infers the employment intensity of growth but also implies the technological intervention, GDP share for public expenditure, policies and implementation. Governments often try to take good policies, but the essential parts are the proper implementation, which is associated with the system's functioning, a conducive socio-political environment and inclusiveness (Aisen and Veiga 2013; Fosu 2001; Alesina et al. 1996). Another important aspect is the public expenditure that energises the job market. In the financial year 2007–2008, the public expenditure in India was nearly 30 per cent of the GDP; after that, it started to decline. It has recently reached the bottom level (Basu 2020). The North-East states are not an exception. The limited budgetary allocation for North Eastern Council (NEC) has affected the accelerating economic progress of the region (Umdor 2016). A declining trend of budget allocation for NEC from 1,485 crores in 2018–2019 to 1,476.28 crores in 2019–2020 and 1,474.49 crores in 2020–2021 has been witnessed (PIB 2021). Moreover, trustworthy ambient, stable political condition, and acceptance of dissent are prerequisites for private investment or Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Divisive politics based on ethnicity jeopardise the investment environment in North-East (Yumnam 2018). Ethnic politics control the legislative assemblies; stable governments are hardly found (Shimray 2004). In addition, illegal taxing and extortion by underground groups (Sharma 2016) and political corruption are rampant (Muhindro 2016; Time of India 2011). The income per capita growth in the North-East is far from inclusiveness and has become a fiasco to incentivise employment opportunities.

In addition to that, it is a broad consensus that youth unemployment leads to insurgency or terrorism (Jelil et al. 2018; Bagchi and Paul 2017; Urdal 2004). If a county fails to provide employment opportunities to its youth bulge, a sense of grievances is fumed. Terrorist groups take advantage of recruiting frustrated youth, resulting in violence increases (Bagchi and Paul 2017; Urdal, 2004). Likewise, in the North-East, economic opportunities in the form of employment by the underground groups lure the educated and unemployed youth. Upadhyay (2006) pointed out that terrorism in North-East has taken a form of ‘criminal enterprise’ and become a ‘lucrative industry’, particularly for the unemployed-educated youth. The Government of India has also expressed grave concern regarding youth recruiting in militancy due to ‘inadequate economic development and employment opportunities’ and ‘corruption in Government machinery’ in the North-East (GOI, 2008, p.146; GOI, 2006, p.2).

9 Section C

9.1 Discussion

Since the balance of intercensal migration in the North-East is negative, more people are leaving than entering the region. It is conspicuous that Nagaland and Mizoram have witnessed an unprecedented growth of out-migrants in the 1990s. Even Assam and Manipur have also experienced a mass out-migration in the 1900s and recorded a persistently negative migration growth rate. On average, 30 per cent of workers migrated from the North-East region to mainland India in the 2011 Census. This tendency is more prominent in Nagaland, Mizoram, Assam, and Manipur. Employment opportunities remain a grave concern in North-East India. Employment elasticity implies that per capita income growth does not lead to employment opportunities, inducing the workers to migrate from North-East into mainland India on a large scale. Not only the labour migration but the student migration at large infers the poor educational provisions in the North-East. A considerable proportion of students, one-fourth of intercensal migration, of Manipur, Mizoram, and Arunachal Pradesh are migrating out. A noticeable aspect of interstate migration from the North-East is the reason for migration ‘other’, which includes the forced migration, is far higher than the Indian average. During the last two decades, the 1990s and 2000s, no large natural disasters occurred with mass casualties in the North-East. Hence, the reason ‘other’ strongly indicates the mass interstate migration induced by ethnopolitical unrest in the North-East.

The 1990s witnessed the pick of ethnopolitical movements in different parts of the North-East. The demand for ‘Nagalim’ (Greater Nagaland) was intensified in the 1990s by the solidarity of the Naga clans spreading over Manipur, Assam, Arunachal, and across the border of Myanmar. In 1997, the Naga ceasefire agreement was signed between the largest Naga group, the National Socialist Council of Nagalim- Isak-Muivah (NSCN-IM) and the Indian Government (GOI 2001). Though the Ceasefire Agreement tried to restore a peaceful ambient in North-East, NSCN—Khaplang faction has engaged in unlawful and violent activities in the Eastern Nagaland and the Tirap and Changlang districts of neighbouring Arunachal Pradesh. The demand for ‘Nagalim’, along with a separate flag and constitution, necessitates a massive re-organisation of neighbouring states, which is not only a matter of widespread discontent and agitation, but may also fuel the ethnic conflict and resume insurgency at a large scale.

After the Mizoram Peace Accord in 1986, Mizo National Front (MNF) had surrendered all arms, ammunition, and equipment, and Mizoram emerged as a full-fledged state. The 1990s was the formation stage, where the ethnopolitical aspiration for ‘self-determination’ like Lai, Mara and Chakma Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) led to the ethnic conflicts in Mizoram. It was very challenging to tackle by the newly formed government led by MNF. The insurgent activities by the Hmar Tribe for autonomy in Mizoram are still alive. In the 2000s, the situation has improved in Nagaland and Mizoram, and by now, Mizoram is quite a peaceful state (GOI 2008).

Manipur has often been disturbed due to ethnic conflicts and secessionist movements. Hostility between Nagas and Kukis dates back to colonial times (Haokip 2015). The conflict was heavily landed in 1992, and more ruthlessly on 13 September 1993, known as ‘Joupi Massacre’ and observed as ‘Black Day’ every year. NSCN-IM faction uprooted roughly 350 Kuki villages, killed more than 1000 ordinary people, and displaced more than tens of thousands between 1992 and 1997 (Saikia 2018). Kukis residing hilly areas are claiming as ‘Koki-homeland’, which coincides with the ‘Nagalim’ envisioned by the NSCN is a prime cause of conflicts. Naga Ceasefire of 1997 and the latter Framework Agreement of 2015 are not only a matter of ethnopolitical brawl between the two major hilly tribal groups but also involve non-tribal ethnic groups, such as the Meitei and Meitei-Pangal. Manipur also witnessed the Meitei-Pangal riots in 1993 in Imphal valley and the Kuki-Zomi clash in 1997 in Churachandpur District by Kuki militants (Shimray 2004). Apart from inter-ethnic conflicts, separatist movements and incidents of ambushing are common in Manipur. These disturbances are historically rooted. Once an independent princely state, Manipur was merged with Indian Union on 21 September 1949. Hence, a political, social, and emotive issue is associated with the Meiteis. Different Meiteis outfits have emerged from time to time with a demand for a sovereign nation, almost resembling the Kashmir issue.

Assam has also been suffering problems ranging from internal ethnic conflict for autonomy or a separate state like the Bodoland Movement, and separatist demands for sovereignty by the United Liberation Front of Asom to controversies over linguistic and religious issues and tension on illegal immigrants from neighbouring Bangladesh. Recently, the political uproar over the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) of 2019, both dealing with the ‘outsider’, has brought worrisome consequences. Assam has witnessed periodic riots between plane land tribes, Bodos, and Bengali speaking Muslims. The ‘Nellie Massacre’ in 1983 was one of the worst pogroms since World War II, and further violence on 20 July 2012 and 01 May 2014 (Choudhary 2019).

A contrasting pattern of migration flow to the mainland Indian States from the North-East is portrayed in the 2001 and 2011 Census. North-East migrants in the North and East Indian States have declined, whereas the South Indian States have witnessed an increase of North-East people. There is a significant drop of interstate migrants entering Delhi from the North-East and South India from the 2001 to 2011 Census. The North-East migrants to Delhi have dropped 26 per cent, and South Indian migrants to Delhi have dropped 20 per cent during 2001–2011, and migrants from UP and Bihar have filled up that vacuum (Singh and Gandhiok 2019). Fewer people from the North-East States are ‘making Delhi their home’ (Singh and Gandhiok 2019) and moving South instead. This phenomenon could be attributed to the sporadic racial violence against North-East people in mainland India (McDuie-Ra 2014; 2012). In Delhi and its surroundings, UP and Bihar, violence against north-easterners are rampant.

9.2 Conclusion

Eight North-East states of India share around four per cent of the country’s total population. Though it is a small proportion, it is significant in the demographic and ethnopolitical perspective. North-East’s 45.8 million people divide into many ethnic groups, and most of them are recognised as Scheduled Tribes (ST), around 28 per cent or 12.7 million in the 2011 Census. Hilly states like Mizoram, Meghalaya, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh are predominated (more than two-thirds) by the tribal. Tribal communities are primarily dependent on agriculture and forest-based livelihoods (Majaw 2021). According to the report on ‘Tribal Health in India’ in 2018, more than half the country’s 104.3 million tribal population have to reside outside India’s 809 tribal majority blocks (GOI 2018). Their migration from tribal to non-tribal areas are primarily searching for job and educational opportunities (GOI 2018). Tribals of the North-East are not an exception. Irrespective of social groups, on average, nearly 60.0 per cent of migrants prefer to migrate to mainland India for various reasons, primarily for work/employment and education. In the last couple of decades, more people are moving out than entering the region. The negative balance of migration has gradually declined, and some states have already started to gain.

North-East India is endowed with natural resources and eco-tourism for its pristine beauty. The frontier region is a significant geostrategically and potential corridor for foreign trade with South and South-east Asia. Since the financial year 1993–1994, North-East has witnessed the positive growth of the economy. Income growth per capita has been observed higher than the Indian average in the 2000s and the first half of the 2010s. But the income growth in North-East states lacks inclusiveness and fails to sensitise employment opportunities, which induce the mass exodus of workers from North-East states in the 1990s and 2000s. Not only the labour migration but the student migration is also conspicuous, which exhibits the weakness of the educational system. States, namely Manipur, Mizoram, and Arunachal Pradesh, witness a very high level of student migration.

Inclusive development is deep-rooted in the peaceful socio-cultural and political atmosphere and trustworthy economic conditions. North Eastern Council (NEC), a ‘regional planning body’, constituted under the NEC Act of 1971 with the great hope of accelerating development and addressing the region's common security challenges. The member states have widely criticised the functioning of the council (Umdor 2016). The council has limited power to sanction big projects. Limited budget allocation to NEC and delayed sanction of funds severely hamper the acceleration of developments in the region (Umdor 2016). Moreover, the council lacks expertise in many areas, poor assessment and review processes, and the absence of a funding mechanism to maintain assets (Umdor 2016). In addition, ‘progressive erosion of states’ authority’ to uphold ‘rules of law’ (Yumnam 2018; Upadhyay 2006) and weak governance capacities shackle their ability for effective planning and execution (Kundra 2019). Security cannot be separated from the issues of development, and it is also an important mandated function of NEC, which has been shown a severe apathy in dealing (Kundra 2019; Umdor 2016). In 2011, a separate ministry, the Ministry of Development of the North Eastern Region, was set up for better care of economic and social development in the North-East region. Governmental structures, legislation, policies, and various agreements or accords are not the sole criteria of development. Proper implementation is crucial along with these. Ethnopolitical unrest for self-determination or sovereignty, illegal taxing and extortion, ambushing by different ethnic outfits, and rampant corruption are major predicaments to the execution of any project and a hindrance for investment. In addition to that, more than sixty years of enforcement of draconian law, AFSPA of 1958, and militarisation under the act subdue the culture, fundamental human rights, and social well-being of the North-East peoples. The non-armed public got frustrated and depressed and migrated out of states in the 1990s and 2000s.

On the other hand, intercensal migration in the North-East region, especially from geographic proximity states like Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh, has remained more or less the same in the 2001 and 2011 Census and is expected to decline in the forthcoming Census. Since the mid of 2019, Assam had been rumbling when more than 1.2 million Hindus out of 1.9 million were excluded from the NRC list published on 31 August 2019, and later erupted in a violent demonstration over the CAA of 2019. These tremors have spread over the country and reeked of the anti-migration image of Assam. The President of India issued the Adaptation of Laws (Amendment) Order of 2019 to amend the historic law, the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation (BEFR), 1873, where areal exclusion (from Assam) and inclusion under Inner Line Permit (ILP) system had been done. An ILP is a travel document required by non-domiciled persons to enter the region. The area under the ILP system is exempted from the provision of CAA passed in December 2019. On 10 December 2019, Manipur was brought under ILP, and just a day before, on 9 December 2019, the Nagaland government extended IPL to include Dimapur. Meghalaya Assembly also adopted a resolution favouring ILP in December 2019 but could not implement it like Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, and Nagaland. However, the ILP system not only controls the movement of labourers from mainland Indian states but also bars the spontaneous movement of ethnic groups among the sister states.

Nowadays, North-East is relatively peaceful, and there have been no massive demonstrations witnessed in the 2010s. The demand for ‘Nagalim’ by certain Naga factions is still a great apprehension, which often turns into ethnic hostility and creates political unrest. Besides, unemployment in North-East is still high and growing. Though the increasing unemployment rate gets mass anxiety in every Indian, in the North-East, this has become gradually severe. Some North-East states like Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Tripura have already touched a double-digit unemployment rate in the 2010s. In addition, the annual income growth has started to decline since the beginning of the 2010s. Furthermore, the pandemic Covid-19 hard-hit the economic growth and employment in the recent time.

There is no hope of reducing North-Eastern labour migrants to mainland India in the figures of the forthcoming Census. But it can be expected that there may be a decline in student migrants. Because of the many centrally funding educational institutions, research centres, tribal universities, sports and cultural universities have been set up and upgraded to the existing ones in the 2010s. State governments have also taken initiatives. Hence, nowadays, there is much more scope for studying and pursuing research within the North-East region.

Notes

The proportional change of employment rate is larger than the change of NSDP per Capita growth.

The proportional change of employment rate is equal to change of NSDP per Capita growth.

References

Aisen, A., and F.J. Veiga. 2013. How does political instability affect economic growth? European Journal of Political Economy 29 (2013): 151–167.

Alesina, A., O. Sule, R. Nouriel, and S. Phillip. 1996. Political instability and economic growth. Journal of Economic Growth 1 (2): 189–211.

Bagchi, A., and J.A. Paul. 2017. Youth unemployment and terrorism in the MENAP (Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, and Pakistan) region. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 64 (2018): 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2017.12.003.

Banerjee, S., J.Y. Gerlitz, and B. Hoermann. 2011. Labour migration as a response strategy to water hazards in the Hindu Kush-Himalayas. Kathmandu: ICIMOD.

Basu, K. 2020. India’s divisive politics, intolerance a major obstacle to economic growth', the WIRE. Retrieved May 19, 2022, from https://thewire.in/economy/watch-kaushik-basu-karan-thapar-chief-economic-covid-19-world-back.

Belcher, J.C., and F.L. Bates. 1983. Aftermath of natural disasters: coping through residential mobility. Demography 7 (2): 118–128.

Brahmachari, D. 2019. Ethnicity and violent conflicts in northeast india: Analysing the trends. Strategic Analysis 43 (4): 278–296.

Census of India. (1991). Migration tables, CD-ROM. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India, Government of India.

Census of India. 2001. Migration tables- (D- Series). From https://censusindia.gov.in/DigitalLibrary/TablesSeries2001.aspx.

Census of India. 2011. Data on migration 2011. From https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/migration.html.

Choudhary, R. 2019. Nellie massacre and ‘citizenship’: When 1,800Muslims were killed in Assam in just 6 hours. The Print, 18 February 2019, from https://theprint.in/india/governance/nellie-massacre-and-citizenship-when-1800-muslims-were-killed-in-assam-in-just-6-hours/193694/.

CSO. 2014. Databook for PC’. Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation (MOSPI), GOI, from https://niti.gov.in/planningcommission.gov.in/docs/data/datatable/data_2312/comp_data2312.pdf.

Das, B., and A. Mistri. 2015. Is nativity on rise? Estimation of interstate migration based on census of india 2011 for major States in India. Social Change 45 (1): 137–144.

Dikshit, K.R., and J.K. Dikshit. 2014. North-east India: Land, people and economy. Heidelberg: Springer.

Feng, Yi. 1997. Democracy, political stability and economic growth. British Journal of Political Science 27 (3): 391–418.

Fosu, A.K. 2001. Political instability and economic growth in developing economies: Some specification empirics. Economics Letters 70 (2001): 289–294.

GOI. 2001. Question No: 297 on Ceasefire Agreements, Raised by mr. Jayanta Rongpi, MP, Answer on: 24.07. 2001 by Home Affairs, Lok Saba. from http://eparlib.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/408376/1/24972.pdf.

GOI. 2006. Annual report, 2004–05, Ministry of Home Affairs, GOI. from https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/AnnualReport_04_05.pdf.

GOI. 2008. Capacity building for conflict resolution. Second Administrative Reforms Commission, GOI. from https://darpg.gov.in/sites/default/files/capacity_building7.pdf.

GOI. 2018. Tribal health in India: Bridging the gap and a roadmap for the future. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), Ministry of Tribal Affair, GOI. from http://nhm.gov.in/nhm_components/tribal_report/Executive_Summary.pdf.

Haokip, T.L. 2015. Ethnic separatism: The Kuki-Chin insurgency of Indo-Myanmar/Burma’. South Asia Research 35 (1): 21–41.

Hoenig, P., and K. Kokho. 2018. Armed opposition groups in northeast India: The Splinter scenario. In Northeast India: A reader, ed. B. Oinam and D.A. Sadokpam, 41–51. New Delhi: Routledge.

ILO. 2018. Employment-rich Economic Growth. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/dw4sd/themes/employment-rich/lang--en/index.htm.

Jelil, M. A., Bhatia, K., Brockmeyer, A., Do, Q.T., Joubert, C. 2018. Unemployment and violent extremism: Evidence from daesh foreign recruits. World Bank Group, Policy Research Working Paper (WPS) 8381. from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/29561/WPS8381.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y.

Kapsos, S. 2005. The employment intensity of growth: Trends and macroeconomic determinants. Employment Strategy Department, International Labour Office. from http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_elm/documents/publication/wcms_143163.pdf.

Kipgen, N. 2013. Politics of ethnic conflict in Manipur. South Asian Research 33 (1): 21–38.

Kundra, A. 2019. Realise the potential of the North Eastern Council. Hindusthan Times, Sep 26, 2019 08:41 PM IST. from https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/realise-the-potential-of-the-north-eastern-council/story-vsKCoecueMrKTEgdKDmeqK.html.

Lusome, R., and R. B. Bhagat. 2006. Trends and Patterns of Internal Migration in India, 1971–2001. In The Annual Conference of Indian Association for the Study of Population (IASP), Thiruvananthapuram.

Majaw, B. 2021. Indo-Bangladesh borderland issue in Meghalaya. South Asian Research 18 (1): 22–37.

Marchang, R. 2017. Out-migration from North Eastern region to cities: Unemployment, employability and job aspiration. Journal of Economic & Social Development 13 (2): 43–53.

McDuie-Ra, D. 2012. Cosmopolitan tribal: Frontier migrants in Delhi. South Asian Research 32 (1): 39–55.

McDuie-Ra, D. 2014. Ethnicity and place in a ‘disturbed City’: Ways of belonging in Imphal, Manipur. Asian Ethnicity 15 (3): 374–393.

Misra, S., and K. S. Suresh. 2014. Estimating employment elasticity of growth for the Indian economy. RBI Working Paper Series, Department of Economic and Policy Research. from https://www.rbi.org.in/SCRIPTs/PublicationsView.aspx?id=15763.

Mistri, A. 2019. Is the migration from Indian Sundarban an environmental migration? Investigating through sustainable livelihood approach (SLA). Asian Profile 47 (3): 195–219.

Mistri, A. 2021. Migrant workers from West Bengal since 1991: From the left to TMC Government. Economic and Political Weekly 56 (29): 21–26.

Mistri, A., and B. Das. 2020. Environmental change, livelihood issues and migration sundarban biosphere reserve, India. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Muhindro, L. 2016. Corruption and election in conflict Northeast India. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention 5 (9): 38–45.

NSSO. 1997, 2001, 2006, 2010, 2011 and 2014. Employment and unemployment situation in India. MOSPI, GOI.

NSO. 2019. Periodic labour force survey (PLFS) 2017-18. MOSPI, GOI.

Perch-Nielsen, S. 2004. Understanding the effect of climate change on human migration: The contribution of mathematical and conceptual models. department of environmental studies. Zurich: Swiss Federal Institute of Technology.

PIB. 2021. Budgetary allocation for North Eastern Council. Ministry of Development of North-East Region, GOI. From https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1779733.

Saikia, A. 2018. 25 years after naga-kuki clashes in Manipur, reconciliation is still elusive. Scroll.in. On 14 September 2018. From https://scroll.in/article/894324/25-years-after-naga-kuki-clashes-in-manipur-reconciliation-is-still-elusive.

Sharma, S. K. 2016. Taxation and extortion: A major source of militant economy in Northeast India. New Delhi: Vivekananda International Foundation. https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/Taxation%20and%20Extortion%20A%20Major%20Source%20of%20Militant%20Economy%20in%20Northeast%20India.pdf.

Shimray, U.A. 2001. Ethnicity and socio-political assertion: The Manipur experience. Economic and Political Weekly 36 (39): 3674–3677.

Shimray, U.A. 2004. Socio-political unrest in the region called North-East India. Economic and Political Weekly 39 (42): 4637–4643.

Singh, P., and J. Gandhiok. 2019. Fewer people from northeast and southern states making Delhi their Home. The Times of India. On 11 November 2019, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/fewer-people-from-northeast-and-southern-states-making-delhi-their-home/articleshow/70458576.cms.

Times of India. 2011. Root out corruption from the system, cries northeast. Times of India. On 11 August 2011, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/guwahati/root-out-corruption-from-the-system-cries-northeast/articleshowprint/9652976.cms.

Umdor, S. 2016. Challenges before the North Eastern council. The Shillong Times. On May 26, 2016. From https://theshillongtimes.com/2016/05/26/challenges-before-the-north-eastern-council/

Upadhyay, A. 2006. Terrorism in the North-East: Linkage and implications. Economic and Political Weekly 41 (48): 4993–4999.

Urdal, H. 2004. A clash of generations? Youth bulges and political violence. International Studies Quarterly 50 (2006): 607–629.

Yumnam, A. 2018. Critiquing the development intervention in the northeast. In Northeast India: A reader, ed. B. Oinam and D.A. Sadokpam, 406–419. Routledge.

Acknowledgements

The author is thankful to Prof. Kh. Pradeep Singh and Dr. A. Mangalam, Dept. of Geography, Manipur University, for sharing their in-depth knowledge and views on ethnic history and conflicts in the North-East.

Funding

There was no funding for the research work; it is the research of personal interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The work has not been published before, and it is not under consideration for publication anywhere else. There was no funding for continuing the research work, and no financial interest was involved with it and will not be in future. The work is only for the dissemination of knowledge and policy intervention for the development.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mistri, A. Migration from North-East India During 1991–2011: Unemployment and Ethnopolitical Issues. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 65, 397–423 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00379-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-022-00379-5