Abstract

Youth experiencing systemic oppression(s) face heightened challenges to wellbeing. Critical consciousness, comprised of reflection, motivation, and action against oppression, may protect wellbeing. Wellbeing here refers to mental, socioemotional, and physical health. The aim of this systematic review was to synthesize research on the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing among adolescents and young adults (ages 12–29). Five databases (PsycInfo, PsychArticles, ERIC, Sociological Abstracts, and PubMed) were searched systematically using keyword searches and inclusion/exclusion criteria; 29 eligible studies were included. Results demonstrated that the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship varied by critical consciousness dimension and age. The studies of adolescents most often focused on racial/ethnic marginalization and found critical motivation most strongly associated with better wellbeing. The studies of young adults focused on young adult college students and identified mixed results specifically between activism and mental health. Study methods across age spans were primarily quantitative and cross-sectional. Research on critical consciousness and wellbeing can benefit from studies that consider multiple critical consciousness dimensions, use longitudinal approaches, and include youth experiencing multiple and intersecting systems of privilege and marginalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Critical consciousness has been an increasing focus of research over the past two decades, particularly in relation to youth development (Heberle et al., 2020). Critical consciousness is a process through which individuals develop their analysis of structural oppressions and build agency to enact change to transform oppressive systems (Diemer et al., 2020; Freire, 1973). For youth experiencing societal marginalization, critical consciousness has important implications for multiple developmental domains including education (Seider & Graves, 2020) and career development (Uriostegui et al., 2021). Yet, the effects of critical consciousness for youth’s wellbeing are unclear (Heberle et al., 2020). Wellbeing includes one’s mental, socioemotional, and physical health (Saylor, 2004). Critical consciousness’s relationship to wellbeing may be determined by a complex confluence of factors including context (Hope et al., 2018), experiences across marginalizing systems (Fine et al., 2018), and developmental period (Tyler et al., 2020). Clarifying the links between critical consciousness and wellbeing across contexts, marginalizing systems, and developmental periods will help researchers and practitioners better understand how youth’s wellbeing is affected as they undergo the important work of critical consciousness (Heberle et al., 2020). Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review is to assess if, and under which conditions, critical consciousness relates to wellbeing.

Critical consciousness

Critical consciousness is conceptualized as a liberatory process (Freire, 1973), with much of contemporary critical consciousness research considering three reciprocal dimensions: (1) critical reflection, or analysis of inequality, (2) critical motivation (sometimes termed political efficacy, agency, or empowerment), or, perceptions of one’s ability to enact change, and (3) critical action, or participation in efforts to change inequalities (Rapa et al., 2020). Each dimension is complex. Critical reflection considers whether individuals are aware of oppressions across multiple dimensions, perceive society to be inequitable for groups experiencing historic and ongoing marginalization, and attribute inequities to societal structures (Hope & Bañales, 2019). Critical motivation centers individuals’ desires to create change and perceived capabilities to enact change, both individually and collectively (Godfrey et al., 2019a). Critical action focuses on individuals’ involvement in challenging inequalities through organizations, protests, or participation in the political process. Critical action may also extend beyond political engagement to include actions like service (Tyler et al., 2020) and social media engagement (Wilf et al., under review) aimed at challenging and redressing inequitable systems.

Dimensions of critical consciousness and related processes have been studied through several distinct theoretical perspectives including sociopolitical development theory (Watts et al., 2003), psychological empowerment theory (Rappaport, 1987), and system justification theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994). To understand the relationships between critical consciousness and wellbeing, it is important to synthesize across theories to consider how the critical consciousness dimensions of critical reflection, motivation, and action are conceptualized.

Critical reflection, or analysis of inequality, is a core element of sociopolitical development theory, given that this theory emphasizes developmental processes and interrelations between critical reflection, motivation, and action (Watts et al., 2011). Critical reflection is also captured through psychological empowerment theory’s concept of cognitive empowerment, which assesses awareness of the sociopolitical environment and understanding of how to make change within these systems (Christens et al., 2016). Indeed, sociopolitical development theory and psychological empowerment are more similar than different, and use different terminology to conceptualize individuals’ processes of resisting oppressions (Christens et al., 2016; Watts et al., 2003). Meanwhile, system justification theory suggests that individuals are motivated to support current social systems because they exist (Jost & Banaji, 1994). The theory only speaks directly to the critical reflection dimension of critical consciousness, and argues that people may ignore parts of the system that are not fair or good, even at the expense of their personal or group’s interest. Youth who demonstrate system justification tend to ignore, deny, or justify extant oppressive conditions (Godfrey et al., 2019b), and therefore may be considered low on critical reflection. Including cognitive empowerment and low system justification beliefs into the conceptualization of critical reflection can lead to a more robust investigation of links from critical reflection to wellbeing.

Critical motivation is known by many names, and was originally termed agency and later efficacy in an sociopolitical development framework, with these constructs aimed at understanding competence to challenge inequalities (Watts et al., 2011; Watts & Gusseous, 2006). Critical motivation can also be considered as a component of psychological empowerment theory, which conceives the dimension of emotional empowerment as competence, motivation, and sociopolitical control for changemaking, and also includes a dimension of relational empowerment that captures collective competence and collaborative mobilization for changemaking (Christens et al., 2016). The terminology of critical motivation has been adopted more recently to more broadly encompass individuals’ perceived abilities to advance equity and justice, either individually or collectively, and desires and commitments to make such change (Rapa et al., 2020). This broader conceptualization of critical motivation is advantageous for understanding links to wellbeing, due to its inclusion of various motivations for challenging oppression that go beyond personal competence and include collective agency as well as values, goals, and hopes.

Within an sociopolitical development theory framework, critical action, or behaviors that challenge inequalities and oppressive systems, was originally described as societal involvement to encompass many different ways that youth participate in civic action (Watts et al., 2003), and more recently has been termed sociopolitical action, with scholars recognizing that the conceptualization and measurement of these actions vary (Watts & Hipólito-Delgado, 2015). Psychological empowerment theory conceptualizes action as behavioral empowerment, and casts a net that includes community, organization, and political participation but also other behaviors to cope with the circumstances of marginalization (Christens et al., 2016). In the literature, critical action is most often operationalized in terms of political involvement, which includes activism and other forms of political actions. Youth activism involves a process of seeking influence on public policy and transforming institutions (Kirshner, 2007), thus involving actions to change the status quo in society (Klar & Kassar, 2009). Similarly, other forms of political involvement can include efforts to transform political systems, such as through signing a petition, supporting a political candidate, or using social media to support a political cause (Ballard et al., 2020; Wilf & Wray-Lake, 2021). Not all political involvement may be critical. For instance, voting is often considered to involve working within existing political structures rather than challenging them (Ballard et al., 2020). From a critical consciousness framework, critical actions are most clearly understood as political or other forms of action that aim to challenge or dismantle marginalizing systems.

The relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing

Although critical consciousness is framed as a process of liberation that evokes hope and empowerment (French et al., 2020), the process of confronting structural oppressions may catalyze a series of wellbeing ramifications such as stress or anxiety (Ballard & Ozer, 2016). Engagement in critical consciousness may be supported through interpersonal and institutional mechanisms that reduce potential negative effects of critical consciousness engagement on wellbeing (Heberle et al., 2020). For example, through youth activist programs, youth may be able to form connections with peers and adults that foster a sense of connectedness, promoting wellbeing (Ballard & Ozer, 2016). Further, an institutional culture of youth-led action may be particularly influential on youth’s sense of efficacy (Poteat et al., 2020), which may similarly promote wellbeing. Thus, it is important to consider salient conditions that may influence the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing.

In reviewing the research on critical consciousness and wellbeing, it is also important to conceptualize wellbeing as a multidimensional construct to more thoroughly understand any potential benefits and consequences experienced in the context of critical reflection, motivation, and action. In this review, wellbeing encompasses mental health, physical health, and socioemotional health. Mental health captures constructs related to one’s psychological state, including internalizing symptoms of anxiety and depression, and externalizing symptoms such as disruptive conduct (Chan et al., 2008). Physical health can be measured by biological function and the structural integrity of the body, including aspects such as blood pressure or bone density (Saylor, 2004). An element to youth’s physical and mental health is the ways in which youth may engage in health risk behaviors (Rew & Horner, 2003). These health risks include substance use (Miller et al., 2007), which may imperil wellbeing. For example, youth substance use has been correlated with poorer diet, exercise, and sleep (Ames et al., 2020). Socioemotional health considers the development of a youth’s emotional expression, regulation and experience in the context of one’s social and cultural environment (Madigan et al., 2018; Yates et al., 2008). In adolescence and young adulthood, socioemotional development is often operationalized through constructs such as sense of purpose and sense of happiness (Chan et al., 2021). Meanwhile, positive youth development serves as a broad term to promote young people’s wellbeing (Christens & Peterson, 2012), which is often operationalized as the 5 C’s: confidence, caring, character, connection, and competence (Lerner et al., 2005). Within the broad domain of socioemotional development, many strengths-based measures aim to capture young people’s assets and capacities to function adaptively in their social environments and to live a fulfilling life (Benson & Scales, 2009).

Current study

Critical consciousness may have important implications for youth’s wellbeing, yet the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing has yet to be systematically synthesized. The purpose of this systematic review was to comprehensively assess the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing in adolescents and young adults. This study assessed the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing through considering potential developmental differences by age. The study also aimed to examine which critical consciousness dimensions are related to which facets of wellbeing within each developmental period. The study also evaluated the physical and social contexts that support youth’s wellbeing in relation to critical consciousness, including the role of elements like organizations and schools in influencing the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship.

Methods

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Statement (PRISMA, Moher et al., 2009) guidelines, a replicable search process was implemented.

Eligibility

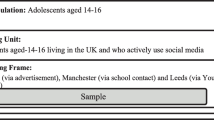

The following inclusion criteria were instituted: (1) empirical studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods approaches; (2) published in a peer-reviewed academic journal; (3) clearly defined critical consciousness or critical consciousness-related construct or phenomena; (4) clearly defined wellbeing construct or phenomena; (5) focused on youth (i.e., adolescents or young adults, ages 12–29).

Information sources and search

Four electronic reference sources were initially used to identify relevant studies on September 29, 2021: APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, ERIC, and Sociological Abstracts. A fifth electronic reference database, PubMed, was reviewed in October 2021 to determine if additional articles were identified; this search produced only duplicate articles. Advanced search options using Boolean operators AND/OR were used to identify a series of keywords included in study abstracts; the limit on abstracts was to ensure a focused review. Search terms included terms associated with critical consciousness (separated by OR): critical consciousness, sociopolitical development, activism, psychological empowerment, political action, critical analysis, critical reflection, critical motivation, political efficacy, critical action, political engagement, political participation, critical agency, systems attribution, system attribution AND search terms associated with wellbeing (separated by OR): wellbeing, well-being, well being, mental health, socioemotional, thriving, positive youth development, health, stress, wellness, risk behavior, substance use, health behaviors AND search terms associated with the study population: youth, adolescent, adolescence, young adult, emerging adult, young adult, college student, teen, early adult.

Study selection

To screen eligible articles, the procedure was as follows: duplicate articles were removed; abstracts were reviewed to assess potential relevance; full texts of articles were reviewed and removed based on inclusion/exclusion criteria, while potential articles were added based on in-text citations. These potential articles were also reviewed and added based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. Ultimately, 29 articles were included in the formal analysis (Fig. 1). Of these 29 studies, there were 26 unique study samples. There were three pairs of studies that draw from the same samples: Ballard et al., 2019b and Wray-Lake et al., 2019; Lardier et al., 2018 and 2020; and Fine et al., 2018 and Frost et al., 2019.

Data extraction process

EMC developed an a priori codebook to systematically review each article. The codebook was piloted with ten articles and reviewed by LWL and one additional advisor to the study. Upon finalizing the codebook, EMC coded the 29 articles, consulting with LWL and AKC when questions arose. The coding process implemented a combination of “multi-choice” options and write-in options to collect relevant information on each study.

Participants. Details about the sample from each study were recorded, including: age, race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic position, sexual orientation, and immigrant-origin status. Also included was the broader context for the study (e.g., students at one school).

Method. Articles were first coded for their methodological approach (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal; qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods). Information was collected on the way the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship was studied (i.e., measures and analytic approach). Finally, resultant findings of the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship(s) for each study were recorded.

Salient conditions. The codebook recorded any salient contexts or sociopolitical factors attributed to influencing the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship. Thus, conditions included certain spaces (e.g., organizations, school programs) and/or broader sociopolitical forces (e.g., heterosexism, racism) within which authors contextualized the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship.

Risk analysis

Inspired by other quality assessments that relied on subjective assessment of study design and analysis approaches, each article’s research question(s) or aim(s), method, sample, and findings was recorded. A study quality score was developed to consider the variety of articles reviewed. Because only longitudinal studies had temporality (i.e., critical consciousness at one time point, wellbeing subsequently), those were distinguished. Quantitative studies were further assessed for whether these articles adjusted for confounders. In sum, quantitative articles were codified into the following categories: longitudinal or not, controlled for confounding or not. For qualitative studies, longitudinal studies were similarly distinguished, and then assessed for whether they used a coding verification process (Kmet et al., 2004), a criterion deemed parallel to assessments of confounders for quantitative studies (see Table 1).

Results

To conceptualize the field studying the relationship between critical consciousness (or related theories and constructs) and wellbeing, the results are divided into five sections. First, eligible studies are described. Most studies (n = 16) conducted quantitative analyses of cross-sectional data, and there was age-based variation in the frequency of critical consciousness-related frameworks (i.e., psychological empowerment framework used exclusively in adolescence; activism studied more often in young adulthood) and wellbeing dimensions (i.e., heavier focus on mental health in young adulthood). The next three sections are divided by adolescent samples, combined adolescent and young adult samples, and young adult samples, respectively. Studies on adolescents focused primarily on youth of color, particularly youth from low-income and urban backgrounds, while the studies of combined adolescent and young adult samples were diverse. The studies on young adults focused primarily on young adult college students. Embedded within the adolescent and young adult results are sections on the salient conditions and factors contributing to critical consciousness’s relationship to wellbeing. For adolescents, six studies found after-school and school-based organizations to play a supportive role in critical consciousness and wellbeing development; for young adults, three studies suggested predominantly White college institutions challenged racially/ethnically marginalized youth’s wellbeing as they engaged in critical consciousness. Table 2 provides the citations for the 29 studies reviewed, as well as each study’s methods, sample, critical consciousness and wellbeing constructs, context, and main findings.

Description of eligible studies

Out of 29 studies to date, researchers have used mainly quantitative (n = 21) and cross-sectional (n = 21) designs. Across ages, longitudinal (n = 8) designs were less common, as were studies using qualitative (n = 6) and mixed methods (n = 6). More than half focused on adolescents (n = 16; 55%); 14 out of these 16 studies focused specifically on adolescents of color. In adolescence, psychological empowerment frameworks were most common (n = 10), followed by critical consciousness frameworks (n = 4), with wellbeing often considered through mental (n = 5) and socioemotional (n = 7) health, as well as risk behaviors (n = 7). Articles on young adulthood (n = 9) centered activism (n = 7) and mental health (n = 7). There were four studies that included adolescents and young adults within their samples; these articles also focused on activism (n = 3) and mental health (n = 3). Focus on political behaviors (n = 2) and physical health (n = 3) were also uncommon. Also uncommon was a focus on youth’s experiences with gender (n = 7), sexual orientation (n = 6), and/or immigrant-origin status (n = 2). The study of critical consciousness and wellbeing has increased over time, particularly since 2018 (see Fig. 2).

The critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship in adolescence

Sample characteristics. Adolescent studies (n = 16) comprised 55% of overall studies in the review. The bulk (87.5%) of these studies focused on majority Black, Latinx, (and sometimes Asian) samples, contextualizing critical consciousness development in relation to racial/ethnic marginalization (e.g., Christens & Peterson 2012; Ozer & Schotland, 2011). Within the group of studies focused on adolescents of color, 56% of studies focused on urban and low-income youth (e.g., Bowers et al., 2020; Lardier et al., 2018). Meanwhile, Tyler et al., (2019) comparatively studied Black and White low and middle income youth. Only Montague and Eiora-Orosa (2018) did not name the race/ethnicity of participants, but suggested they came from a privileged background; this study was also the only study of adolescents outside of the USA, based in the United Kingdom.

While race/ethnicity, socioeconomic position, and urbanicity were often centered, less frequent and consistent consideration was given to other marginalizing forces. In terms of gender, three studies of adolescence focused on Black and Latina girls (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016; Opara et al., 2020) and one on Black boys (Zimmerman et al., 1999). No studies considered transgender and gender diverse youth (e.g., genderqueer and gender nonbinary youth). One study focused on youth of mixed sexual orientations (Russell et al., 2009). One study included youth’s immigrant-origin status (Godfrey et al., 2019b).

Characteristics of the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing. The evidence largely indicated a positive relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing for adolescents, specifically adolescents of color. Studies suggested that critical consciousness (particularly when operationalized as critical reflection and/or critical motivation) was associated with better mental and socioemotional health, positive youth development, and fewer risk behaviors (e.g., Bowers et al., 2020; Godfrey et al., 2019; Zimmerman et al., 1999), (see Fig. 3).

The studies using a critical consciousness framework (Bowers et al., 2020; Clonan-Roy et al., 2016; Godfrey et al., 2019; Tyler et al., 2019) primarily examined the role of critical reflection (i.e., understanding and analysis of structures of oppression) in relation to wellbeing using quantitative methods. For youth of color in an after-school program for high-achieving students, critical reflection was associated with positive youth development (Bowers et al., 2020). For Black and Latina girls, critical reflection was qualitatively found to support their positive youth development (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016). Yet, critical reflection was uncorrelated with positive youth development for Black middle schoolers and negatively correlated with positive youth development for White youth of middle and low-income backgrounds (Tyler et al., 2019). Godfrey et al. (2019) contextualized critical reflection with the other critical consciousness dimensions, finding that critical reflection in the absence of critical motivation was associated with worse socioemotional health for middle school youth of color. The only study using a systems justification framework similarly found a decline in mental and socioemotional health for youth of color who did not develop critical reflection throughout middle school (Godfrey et al., 2019b).

The ten studies (Christens & Peterson, 2012; Lardier et al., 2019; 2020; Lardier, 2019; Opara et al., 2020a; 2020b; Ozer & Schotland 2011; Peterson et al., 2011; Russell et al., 2019; Zimmerman et al., 1999) guided by psychological empowerment theory and mainly using quantitative methods all identified positive relationships between critical motivation (i.e., one’s agency and motivation to enact change) with adolescents’ mental and socioemotional health, and their risk behaviors. First, Zimmerman et al. (1999) found that sociopolitical control (a common measure of critical motivation rooted in psychological empowerment theory) protected Black boys from feeling helpless and supported their self-esteem. Russell et al. (2009) also qualitatively found that LGBQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer/questioning and others) youth were able to build social support through their involvement in Gay-Straight Alliances, fostering their socioemotional wellbeing.

More recent studies, almost entirely with Black, Latinx, and Asian youth of low-income backgrounds in the USA, quantitatively demonstrated psychological empowerment was also positively associated with fewer risk behaviors (Opara et al., 2020; Peterson et al., 2011) and mental and socioemotional health (Ozer & Schotland, 2011). Further, researchers found that sociopolitical control mediated the relationship between ecological supports and mental health and risk behaviors (Christens & Peterson, 2012), and worked in concert with ethnic identity development to reduce risk behaviors (Lardier et al., 2018, 2020; Lardier, 2019). These findings on the interplay of ethnic/racial identity and social support with sociopolitical control extended to reducing risk behaviors for Black girls specifically (Opara et al., 2020a). In sum, among adolescents, the relationship between psychological empowerment and wellbeing was particularly supported in the literature, corroborated by Godfrey et al., (2019a)’s finding that critical motivation is needed in conjunction with critical reflection to support wellbeing.

Salient conditions: The role of supportive organizations. Six studies, five with adolescents (Bowers et al., 2020; Clonon-Roy et al., 2016; Montague & Eiora-Orosa, 2018; Russell et al., 2009) and one with adolescents and young adults (Sulé et al., 2021), focused on critical consciousness and wellbeing within specific organizations (i.e., school-based and after school programs). These studies found that participation in these organizations supported both the development of critical consciousness and socioemotional health (which included positive youth development) and extended across distinct samples and contexts. Black and Latina girls who engaged with both in-school and after-school programming (Clonan-Roy et al., 2016) developed critical consciousness (primarily critical reflection) in tandem with their positive youth development. For Black, Latinx, Asian, multiethnic, and other youth in a school program for high achieving youth, critical reflection was associated with positive youth development (Bowers et al., 2020). White, Latinx, Black, and Asian-American youth with mixed sexual orientations who engaged in critical consciousness through Gay-Straight Alliance participation were able to also build their self esteem through “feeling good about oneself” (Russell et al., 2009). Through activism in human rights organizations, privileged youth built their socioemotional health (e.g., intrinsic motivation and efficacy; Montague & Eiroa-Orosa, 2018). Black youth in an organization for Black youth built socioemotional wellbeing through fostering positive identities, self-love, and agentic power (Sulé et al., 2021). Together, this collection of primarily qualitative studies showed how participation in critical consciousness-related organizations (which included those focused on both reflection and on action) during adolescence promoted specifically socioemotional wellbeing, which includes positive youth development, and emphasized how these spaces help youth to affirm and appreciate themselves.

Critical consciousness and wellbeing in adolescence and young adulthood

Sample characteristics. The four studies using mixed adolescent and young adult samples were mainly different from studies on adolescence in that they focused on activism (n = 3) and mental health (n = 3). They also focused on youth from distinct positions of privilege and marginalization. The youth herein studied included: socioeconomically privileged German youth ages 8–20 (Boehnke & Wong, 2011), mixed ethnic/racial LGBTQ + youth ages 14–24 across the USA (Fine et al., 2018; Frost et al., 2019), and Black youth in one organization whose ages were not provided (Sulé et al., 2021).

Characteristics of the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing. The four studies using mixed adolescent and young adult samples all found positive relationships between critical consciousness dimensions and wellbeing. Three studies (Boehnke & Wong, 2011; Fine et al., 2018; Frost et al., 2019) found that activism was positively associated with mental health. Boehnke and Wong (2011) used a quantitative longitudinal approach to study German youth’s mental health trajectories in relation to activist participation in the German peace movement, revealing better trajectories for those who were more active in the movement. Fine et al. (2018) and Frost et al. (2019) quantitatively found that activism was positively associated with better mental and physical health, and Fine et al. (2018) was able to corroborate these findings with qualitative data. Interestingly, Frost et al. (2019) highlighted that activism had a stronger effect on mental and physical health for youth of color than White youth, and for transgender and gender diverse youth than cisgender youth. Thus, this study suggested explicitly what other studies may assume, that critical consciousness development may be most beneficial for youth experiencing one or more forms of societal marginalization, a finding potentially corroborated by Tyler et al. (2019)’s evidence that critical consciousness was negatively associated with positive youth development for White youth. Lastly, a methodologically and theoretically distinct study (Sulé et al., 2021) qualitatively examined Black critical consciousness (defined as a critical consciousness evolving specifically from the Black experience in the USA and rooted in Afro-centric values), concluding that participation in an organization intended to foster mainly critical reflection and critical motivation supported Black youth’s socioemotional wellbeing.

The critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship in young adulthood

Sample characteristics. The study of critical consciousness and wellbeing in young adulthood is characterized by a focus on college students. Six of the nine studies worked with USA college student samples (Ballard et al., 2020; Fernández et al., 2018; Hope et al., 2018; Klar & Kassar, 2009; Vaccaro & Mena 2011; Maker Castro et al., 2022). Ballard et al. (2019) and Wray-Lake et al. (2019) used USA national, non-college based samples from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) Study and Chan et al. (2021) studied young adults in Hong Kong, with college attendance not specified. Four studies drew from ethnically/racially diverse national samples (Ballard et al., 2019b, 2020; Maker Castro et al., 2022; Wray-Lake et al., 2019). Three studies focused on college students facing ethnic/racial marginalization with intersecting marginalizing forces: women of color (Fernández et al., 2018), Black and Latinx mainly first-generation college students (Hope et al., 2018,), and LGBTQ + youth of color (Vaccaro & Mena, 2011). The final two studies focused on racially/ethnically dominant groups: predominantly White college students (Klar & Kassar, 2009) and ethnically Han Chinese youth, youth of the dominant ethnicity in China (Chan et al., 2021). One study considered youth’s immigrant-origin status (Maker Castro et al., 2022).

Characteristics of the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing. Across studies, research on critical consciousness and wellbeing in young adulthood primarily focused on activism, with only one study using a critical consciousness framework (Maker Castro et al., 2022) and one study framed as political behaviors, which included questions related to activism (Wray-Lake et al., 2019). Mental health was the primary way in which wellbeing was measured in young adulthood. Together, the studies in young adulthood suggested mixed, and sometimes conflicting, effects on wellbeing, particularly across ethnic/racial groups (see Fig. 3).

Both Ballard et al., (2019b)’s examination of activism and Wray-Lake et al., (2019)’s study of political behaviors find negative associations with mental health within national samples undifferentiated by youth’s identities or social locations using the same Add Health sample. Hope et al. (2018) found activism protective of mental health for Latinx youth, but not Black youth, at predominantly White institutions. Yet, using a broader national sample, Ballard et al. (2020) found opposite results, in that both activism and expressive action (defined as expressing one’s political opinion, including through clothing, art, and/or social media) had negative associations with wellbeing for Latinx youth, as well as White, Asian, and Hawaiian/other race youth, but no significant effect for Black youth. Maker Castro et al. (2021) also found that critical action was negatively associated with socioemotional health (i.e., hopefulness) for Asian youth, but not for other ethnic/racial groups (or groups based on gender, sexual orientation, or immigrant-origin status). The mixed results presented across these three studies together suggested that there may exist complex relationships between one’s ethnic/racial background, critical consciousness, and wellbeing.

Qualitative studies helped to illustrate why the findings may be mixed for young adults in college. Vaccaro and Mena (2011) and Fernández et al. (2018) illuminated the stressors associated with activism for youth experiencing multiple marginalizing systems. Queer youth of color shared that leadership in activism organizations on behalf of the LGBQ + campus community caused burn out, compassion fatigue, and even suicidal ideation (Vaccaro & Mena, 2011), whereas college women of color reflected that while activism against racism on campus helped them to heal from their experiences as a student, it also caused stress and a need for a break (Fernández et al., 2018). These two studies suggested first that actions may evoke different reactions among young adults than adolescents, and second that the campus context may play a role in influencing wellbeing in relation to their critical consciousness.

Two studies suggested that sociopolitical moments may influence young adult critical consciousness. Chan et al. (2021) used a longitudinal design to find that youth activists’ mental health declined over time, and hypothesized that the sociopolitical context, one in which change at the governmental level did not occur, may have influenced the relationship between individuals’ critical consciousness and their mental health. Maker Castro et al. (2022)’s study of USA college students must also be interpreted within a particular time— that of the COVID-19 pandemic. Across their full sample of youth, each critical consciousness dimension was associated with anxiety. Yet, they did not find any significant interactions by sociodemographic groups; perhaps this universally heightened anxiety can be attributed to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Salient conditions: The centrality of structural barriers in college campuses. A subset of young adult studies specifically consider activism in the context of predominantly White institutions (Fernández et al., 2018; Hope et al., 2018; Vaccaro & Mena, 2011). These three studies collectively suggested that, in contrast to the studies focusing on youth organizations, activism for young adults experiencing one or more forms of societal marginalization may lead to negative repercussions for wellbeing. Hope et al. (2018) found that activism exacerbates the negative effect of discrimination on mental health for Black youth. Vaccaro and Mena (2011) found that activism among queer youth of color within the university context was related to poorer mental health due to factors including a lack of safe spaces on campus for youth with multiple marginalized identities. Similarly, Fernández et al. (2018) found activist women of color suffering from mental health challenges due to institutional racism on the university campus in conjunction with a lack of change and a sense that no one else will do the activist work necessary.

Discussion

Critical consciousness appears to shape adolescents’ and young adults’ wellbeing in complex ways. This systematic review of 29 studies across adolescence and young adulthood demonstrated that critical consciousness can be beneficial for youth’s wellbeing, particularly their socioemotional and mental health, and especially if it is developed in a supportive setting. Yet, research suggests systems of privilege and marginalization may still at times obstruct and impair wellbeing as youth engage in critical consciousness. The results further indicate priorities for future research on critical consciousness and wellbeing, including research across dimensions of critical consciousness and wellbeing, youth populations, and methodologies.

Understanding critical consciousness and wellbeing within and across critical consciousness dimensions

There were notable differences in how the critical consciousness dimensions related to different wellbeing measures, as well as differences in which dimensions were studied in each age group. First, critical motivation, most commonly studied in adolescence, demonstrated the most consistent support of wellbeing, extending to mental and socioemotional health and risk behaviors. This finding makes sense given critical motivation’s main objective to empower individuals to move from reflection and action, processes which are closely linked with psychological fortitude (Chan et al., 2021). The studies on critical motivation primarily stemmed from the psychological empowerment literature, and were limited to mainly quantitative, cross-sectional methods with specific populations. Further investigation of critical motivation and wellbeing should use qualitative approaches following the lead of authors herein reviewed (Russell et al., 2011), as well as longitudinal approaches. Moreover, further investigation of critical motivation’s interaction with other critical consciousness dimensions, including how motivation during adolescence may feed action during young adulthood, can further clarify how critical motivation supports action and reflection (Godfrey et al., 2019a).

Critical action, most commonly studied in young adulthood, demonstrated the most mixed relationship with wellbeing. Critical action was mainly studied in relation to mental health, though mixed results extended to other wellbeing domains. For example, activism was associated with positive (Hope et al., 2018) and negative (Ballard et al., 2020) mental health for Latinx college students. These mixed results may reflect ways in which action brings both a sense of solidarity, a “we”, as youth find spaces to heal together from experiences with marginalization (Ginwright, 2010; Diemer et al., 2021), while simultaneously reflecting ways in which action against marginalization can tax one’s capacities (Gorski, 2019). Researchers should consider how acting as part of a collective may facilitate access to supportive spaces that promote healing in the face of enduring oppression. For instance, youth may foment their action in collective “counter spaces”, or safe spaces theorized to provide youth with resources to support their psychological wellbeing as they act against marginalization (Case & Hunter, 2012).

In the future, it will also be important to more closely examine the target of youth’s activism and advance critical action measures that reflect action specifically against marginalization systems. Currently, many quantitative studies are limited by the fact that information regarding why, or with whom, youth engage in activism is not shared (e.g., Ballard et al., 2019b; 2020; Maker Castro et al., 2021). Thus, it is not clear whether activism specifically against marginalizing forces promotes or harms wellbeing. Researchers should also study critical action and wellbeing in adolescent populations. Adolescents are integral members, and often leaders, of contemporary movements like March for Our Lives, #Black Lives Matter, and Fridays for Future (Stone et al., 2021). Adolescents are also adopting social media tools to participate in collective action (Anyiwo et al., 2020; Wilf & Wray-Lake, 2021). The rapidly growing field of social media and wellbeing (Nesi, 2020) can extend to youth’s critical action online. More broadly, how adolescents’ actions on and offline impact their wellbeing should be of interest to researchers seeking to further discover the conditions under which critical action supports wellbeing.

Critical reflection, also mainly studied in adolescence, was often examined in isolation from other dimensions. Overall, critical reflection was the least studied dimension of critical consciousness in relation to wellbeing, contrasting a broader argument that the study of critical reflection has been overly prioritized (Diemer et al., 2021). Critical reflection was also the only dimension to be studied specifically in relation to positive youth development. Studies of critical reflection and socioemotional health among youth experiencing marginalization highlight how reflection can potentially reduce internalized negative feelings of difference based on observed group dynamics and replace those feelings with an understanding that systems are to blame (and to be resisted) for creating these differences (Heberle et al., 2020). Critical reflection may then occur in tandem with hopefulness in one’s ability to make change, though researchers also note that it may be a challenge to at once critically reflect on inequities and feel hopeful about changing them (Christens et al., 2013). The two studies identifying negative relationships included more privileged youth, whose potentially distinct processes of reflection are discussed below. Critical reflection’s relationship to wellbeing merits further attention, especially in relation to mental health, where current evidence is scant, and especially as it interacts with other critical consciousness dimensions. Following a call to extend critical consciousness studies across ages, critical reflection and motivation in relation to wellbeing should both be further studied in young adulthood (Rapa & Geldhof, 2020).

In considering usage of wellbeing measures, physical health most clearly merits additional investigation. Only Fine et al. (2018) and Frost et al. (2019), whose analyses are from the same dataset, find associations with physical health, findings that are corroborated across the broader literature on youth’s civic participation (Ballard et al., 2019a). But these measures use self-reports, and thus measures that can directly account for critical consciousness’s impact on the physical body (e.g., Ballard et al., 2019b) are needed. Conversely, mental health is most commonly studied. Considering mental health’s mixed relationship with critical action, more study in this particular relationship across groups and contexts is needed. Further, a combination of quantitative socioemotional measures and qualitative positive youth development studies can help balance the extant literature and support more robust conclusions. Notably, the term socioemotional wellbeing was interpreted inconsistently. For example, while Godfrey et al. (2019) categorized depressive symptoms as socioemotional wellbeing, this systematic review categorized depressive symptoms as mental health, which is in line with how others use the same indicator (e.g., Hope et al., 2018). Greater consistency in definitions and indicators of wellbeing will help to clarify the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship. Finally, emergent scholarship examines the role of anger in relation to critical action against racism (Bañales et al., 2019). While emotions like anger may catalyze action (Ballard & Ozer, 2016), unregulated emotions can also come at the cost of socioemotional and mental health (Saxena et al., 2011). It may be useful to more closely examine emotions as motivators and consequences of critical consciousness, and how the emotional labor of critical consciousness impacts wellbeing.

Addressing differences by developmental period

The results clearly distinguish between the critical consciousness and wellbeing of adolescents and young adults. For adolescents facing marginalization by race/ethnicity, and often also by socioeconomic position and urbanicity, critical consciousness indeed may be an important supportive factor of their wellbeing. These findings align with the broader literature on the powerful, liberatory effect of critical consciousness for youth facing marginalization (Jemal, 2017). For young adults, the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship appears more complex, mainly because of the mixed results linking activism and mental health, and also because the results extend to both more youth of more privileged and more marginalized positions. Notably, most studies do not span both adolescence and young adulthood, leaving much to question about youth’s longer term critical consciousness development and the ways in which the transition between phases could explain the shift in youth’s wellbeing. Moreover, given that six of the nine studies on young adulthood focused on college-going youth, there are limitations to which experiences in young adulthood are addressed.

For young adults in college, perhaps academic opportunities to further analyze structural oppressions (Fernández et al., 2018) and for leadership and agency to drive critical action (Renn & Ozaki, 2010) expose them to the specific oppressive circumstances of colleges and to systemic barriers when they act (Linder et al., 2019). Together, sensitivity and exposure to oppressive systems may cause mental health challenges like stress and anxiety (Fernández et al., 2018; Hope et al., 2018). Young adults are also more developmentally independent and may navigate adult responsibilities that might be detrimental to their wellbeing, which may subsequently influence their critical consciousness (Vaccaro & Mena, 2011). Yet more, mental health challenges are on the rise in young adult college student populations, and have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (American College Health Association, 2015; Hoyt et al., 2021). Thus, critical consciousness’s association with challenges to wellbeing may in part be because college student populations are prone to the onset and/or diagnosis of various mental illnesses (Pedrelli et al., 2015); critical consciousness development during this period may catalyze mental health challenges, or conversely protect against them (Hope et al., 2018), but research is needed to explain this relationship.

Finally, college campuses themselves may negatively impact the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing, although further research is needed to disentangle the particular influence of systemic oppression on campus from broader oppressions perpetuated by a heteropatriarchal, capitalist, white supremaist society (Smith, 2016). For youth experiencing marginalization on campus, activism may become a necessity, not a choice, and this need to protect one’s humanity through activism is often met with a lack of administrative support and empathy (Linder et al., 2019). Indeed, studies herein reviewed all highlighted ways in which young adult college students experiencing one or more forms of marginalization reported discrimination on campus (Hope et al., 2018) and structural barriers to their activism (Fernández et al., 2018; Vaccaro & Mena 2011). While it is possible that some college and university contexts are providing their student activists with institutional support, no such studies were unearthed in this review. Given that the college campuses are often epicenters of youth activism (Wheatle & Commodore, 2019), and the wellbeing challenges related to activism illuminated in this review, more attention to the wellbeing of college student activists is merited. Also, for researchers of college-enrolled young adults, greater use of a critical consciousness framework should supplement the current focus on activism. Indeed, critical consciousness is studied in college populations (e.g., Bañales et al., 2020; 2021; Pinedo et al., 2021), but has not yet extended to wellbeing relationships, with the exception of Maker Castro et al. (2022).

At the same time, much more attention is needed for young adults not in college, a gap identified in the broader civic engagement literature as well (Fitzgerald et al., 2021). Currently, two studies examined the same national sample not based in college to find a negative relationship between activism/political action and mental health (Ballard et al., 2019b; Wray-Lake et al., 2019). Yet, in these studies, youth experiencing both societal privilege and marginalization are grouped together, potentially hiding important nuances by population. Explicit examination of young adults differentiated by social positions who are fully employed and or pursuing non-academic endeavors is needed to better understand if the challenges to wellbeing in relation to critical consciousness are in fact specific to the college setting, or if it is reflective of this developmental phase. Moreover, for those youth not in college, there is much left to be explored on how young adults navigating contexts like work and family develop their critical consciousness and how their wellbeing evolves.

Expanding across populations

Results reiterate recent calls to consider ethnic/racial identity development in relation to critical consciousness (Anyiwo et al., 2018; Mathews et al., 2019). For example, positive ethnic/racial identity development may be a protective factor for youth’s critical consciousness and wellbeing as they face racial marginalization transitioning from adolescence to young adulthood, particularly in the college context (Hope et al., 2015). At the same time, the study of critical consciousness and wellbeing in relation to ethnic/racial identity should be expanded to consider multiple marginalizing forces (Heberle et al., 2020; Godfrey & Burson, 2018). There was an absence of consideration for youth’s identities in intersecting systems, with exceptions (e.g., Clonan-Roy et al., 2016; Fine et al., 2017), where two or more identities, usually race/ethnicity and gender or race/ethnicity and sexual orientation, were considered. Research on critical consciousness and wellbeing should become increasingly sensitive to how youth resist marginalization across the many dimensions of their lives.

Moreover, the study of critical consciousness and wellbeing should include groups who have historically not been, or rarely been, centered in the current literature, including Indigenous, Middle Eastern and North African, transgender and gender diverse, immigrant-origin, LGBQ+, and disabled youth. This lack of attention may in part be related to original conceptualizations of critical consciousness as work to liberate those experiencing racial and socioeconomic marginalization (Freire, 1973). A focus on the axes of marginalization that work to oppress the aforementioned groups of youth may be able to discover new ways in which critical consciousness supports wellbeing, vitally important given the wellbeing challenges they all face in the USA. For example, immigrant-origin youth may uniquely draw upon transnational contexts (Wilf et al., under review) or draw from their generational position as either first or second generation youth (Karras et al., under review) to inform their critical reflection. These tools for reflection may influence their wellbeing as they resist the xenophobia harmful to their wellbeing (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018).

To that end, all but three of the twenty-nine studies use USA-based samples. Thus, research provides a window into the ways in which critical consciousness and wellbeing relate in the particular context of a country founded in colonial power with a racist, heteropatriarchal, capitalist government (Smith, 2016). The ways in which people resist and work to transform the legacy and perpetuation of oppression in the USA may be distinct from other areas of the world. Indeed, the question of national context is particularly salient when considering that critical consciousness emerged from Brazil, a country part of the Global South, a region characterized by a history of resistance to colonization.

The question of privileged youth’s critical consciousness (e.g., White youth, youth from upper socioeconomic backgrounds) in relation to wellbeing remains relatively obscure, which reflects how the broader literature continues to grapple with what critical consciousness looks like in privileged youth (Heberle et al., 2020). One study suggested that critical reflection among middle and low income White youth may provoke feelings of racial guilt (Tyler et al., 2019), which is proposed to explain the negative association between critical consciousness and positive youth development. Critical consciousness, which is also important for White youth, may have less of a beneficial function for them as they grapple with their role as oppressors. No comparable studies on White youth were identified in the current review, yet it is possible that the negative associations between critical consciousness and wellbeing for privileged youth is also captured in young adult samples where privileged youth were included but not isolated (Ballard et al., 2019b; Wray-Lake et al., 2019). A broader literature suggests that White guilt can catalyze civic action among college young adults (Dull et al., 2021). How this civic action relates to these youth’s wellbeing is a question that can be further explored.

Finally, there were studies of racially and/or economically privileged youth where activism was not explicitly related to youth’s identities (e.g., Boehnke & Wong 2011; Montague & Eiroa-Orosa, 2018). Using distinct methods and samples, these studies found youth activism supportive of wellbeing, suggesting that for those experiencing societal privilege, activism, like other forms of civic participation like voting and service, may benefit wellbeing (Ballard et al., 2019b), particularly when one does not feel under personal attack for their personal identities. It would be useful to further explore this concept, and also see if such an idea extends to those experiencing forms of societal marginalization while advocating for issues unrelated to their identities (e.g., a Latinx youth advocating for human rights in a non-Latinx region of the world).

Methodological advancements

First, methodological expansion should include greater quantitative study of youth program participation and a simultaneous move toward qualitative work more broadly. The former suggestion would help to fortify the positive results about current program participation, while a broader use of qualitative studies could shed further light on explanations for the nuances within the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing. It will also be important to continue examining contextual variables. Variables could be assessed as moderators quantitatively, or they could be central to qualitative investigations into specific physical sites for critical consciousness. Critical consciousness and wellbeing research can also benefit from greater use of longitudinal work, especially that which transcends the adolescent to young adult transition. Indeed, longitudinal work is especially important to better uncovering the developmental components to the intersections of critical consciousness (Heberle et al., 2020) and wellbeing, especially considering how critical consciousness and wellbeing may evolve either in tandem, or perhaps in opposition, and this question can be explored bidirectionally. Meanwhile, a longitudinal study that begins in adolescence and follows youth in divergent young adult tracks of college and work could help to illuminate whether the seemingly worsening effect of critical consciousness on wellbeing is indeed related to context, or to developmental period. Alternatively, researchers could also look at the effect of wellbeing on critical consciousness development (e.g., Costabile et al., 2021, Hope et al., 2020) over time, reversing the way in which the current study conceived critical consciousness to affect wellbeing. Indeed, wellbeing may itself be a necessary precursor for critical consciousness. Critical consciousness demands mental and physical energy and abilities to question and resist structures that are intended to marginalize (Ballard & Ozer, 2016). Future studies should also further consider how the sociohistorical moment influences the critical consciousness and wellbeing relationship (Chan et al., 2021).

Limitations

The current systematic review provides useful insights into the extant research on critical consciousness and wellbeing. Nonetheless, limitations exist. Most clearly, the review is limited to the studies resultant from the search terms. There may be other studies in other search engines that were not identified and may further elaborate on the question of critical consciousness and wellbeing. To help overcome this limitation, the reference list for identified articles was searched and relevant articles were further reviewed. Further, books were excluded from the current study and future research can consider books that may dive more deeply into critical consciousness and wellbeing (e.g., Ginwright 2015; Wray-Lake & Abrams, 2020). Moreover, the current review limited the key search terms to only the abstract. Finally, the review is limited by the search terms themselves; other constructs may be related to both critical consciousness and wellbeing that add additional nuance to the findings. For example, the broader term civic engagement was not included in relation to critical consciousness, nor were wellbeing outcomes that include specific substance use, like alcohol. Despite these limitations, clear trends and themes were evident from the current search, suggesting that studies identified through different mechanisms may align with existing findings.

Conclusion

Adolescents and young adults who face marginalizing systems may respond through developing their critical consciousness. Critical consciousness may then have important implications for youth’s wellbeing (i.e., their mental, socioemotional, and physical health). This study addressed a gap in literature regarding the relationship between critical consciousness and wellbeing across developmental periods, dimensions of critical consciousness and wellbeing, and contexts. As reinforced in this study, critical consciousness may indeed provide support for wellbeing for youth experiencing marginalization, especially for adolescents of color in the context of supportive organizations. But key questions remain as to whether critical consciousness’s benefits for wellbeing extend specifically to youth engaged in critical action, especially young adults. Given that critical consciousness is meant to protect youth who are unfairly and unduly tasked with combating marginalization, it is imperative that the systems perpetuating their marginalization are dismantled and transformed. In the interim, educators and those working with youth must remain vigilant to ensure their support of youth’s critical consciousness does not come at the cost of their wellbeing. It is also important that future research expand the study of critical consciousness and wellbeing to consider how different (and often understudied) dimensions of critical consciousness (e.g., critical action in adolescence, critical reflection in young adulthood) and wellbeing (e.g., physical health) interact over time and across youth populations.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ames, M. E., Leadbeater, B. J., Merrin, G. J., & Thompson, K. (2020). Patterns of marijuana use and physical health indicators among Canadian youth. International journal of psychology, 55(1), 1–12

American College Health Association (2015). American college health association-national college health assessment II: Reference group executive summary spring 2015.Hanover, MD: American College Health Association,132

Anyiwo, N., Bañales, J., Rowley, S. J., Watkins, D. C., & Richards-Schuster, K. (2018). Sociocultural influences on the sociopolitical development of African American youth. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 165–170

Anyiwo, N., Palmer, G. J., Garrett, J. M., Starck, J. G., & Hope, E. C. (2020). Racial and political resistance: An examination of the sociopolitical action of racially marginalized youth. Current opinion in psychology, 35, 86–91

Ballard, P. J., Cohen, A. K., & dPDuarte, C. (2019a). Can a school-based civic empowerment intervention support adolescent health?.Preventive medicine reports,16,100968

Ballard, P. J., Hoyt, L. T., & Pachucki, M. C. (2019b). Impacts of adolescent and young adult civic engagement on health and socioeconomic status in adulthood. Child development, 90(4), 1138–1154

Ballard, P. J., Ni, X., & Brocato, N. (2020). Political engagement and wellbeing among college students. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 71, 101209

Ballard, P. J., & Ozer, E. J. (2016). Theimplicationsofyouthactivismforhealthandwell-being.Contemporaryyouthactivism:AdvancingsocialjusticeintheUnitedStates,223–244

Bañales, J., Aldana, A., Richards-Schuster, K., Flanagan, C. A., Diemer, M. A., & Rowley, S. J. (2019). Youth anti‐racism action: Contributions of youth perceptions of school racial messages and critical consciousness. Journal of community psychology

Bañales, J., Mathews, C., Hayat, N., Anyiwo, N., & Diemer, M. A. (2020). Latinx and Black young adults’ pathways to civic/political engagement. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology,26(2),176

Bañales, J., Pech, A., Pinetta, B. J., Pinedo, A., Whiteside, M., Diemer, M. A., & Romero, A. J. (2021). Critiquing Inequality in Society and on Campus: Peers and Faculty Facilitate Civic and Academic Outcomes of College Students.Research in Higher Education,1–21

Benson, P. L., & Scales, C.,P (2009). The definition and preliminary measurement of thriving in adolescence. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 85–104

Boehnke, K., & Wong, B. (2011). Adolescent political activism and long-term happiness: A 21-year longitudinal study on the development of micro-and macrosocial worries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(3), 435–447

Bowers, E. P., Winburn, E. N., Sandoval, A. M., & Clanton, T. (2020). Culturally relevant strengths and positive development in high achieving youth of color. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 70, 101182

Case, A. D., & Hunter, C. D. (2012). Counterspaces: A unit of analysis for understanding the role of settings in marginalized individuals’ adaptive responses to oppression.American journal of community psychology,50(1–2),257–270

Chan, Y. F., Dennis, M. L., & Funk, R. R. (2008). Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 34(1), 14–24

Chan, R. C., Mak, W. W., Chan, W. Y., & Lin, W. Y. (2021). Effects of Social Movement Participation on Political Efficacy and Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study of Civically Engaged Youth. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(5), 1981–2001

Christens, B. D., Collura, J. J., & Tahir, F. (2013). Critical hopefulness: A person-centered analysis of the intersection of cognitive and emotional empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52(1–2), 170–184

Christens, B. D., & Peterson, N. A. (2012). The role of empowerment in youth development: A study of sociopolitical control as mediator of ecological systems’ influence on developmental outcomes. Journal of youth and adolescence, 41(5), 623–635

Christens, B. D., Winn, L. T., & Duke, A. M. (2016). Empowerment and critical consciousness: A conceptual cross-fertilization. Adolescent Research Review, 1(1), 15–27

Clonan-Roy, K., Jacobs, C. E., & Nakkula, M. J. (2016). Towards a model of positive youth development specific to girls of color: Perspectives on development, resilience, and empowerment. Gender Issues, 33(2), 96–121

Costabile, A., Musso, P., Iannello, N. M., Servidio, R., Bartolo, M. G., Palermiti, A. L., & Scardigno, R. (2021). Adolescent Psychological Well-being, Radicalism, and Activism: The Mediating Role of Social Disconnectedness and the Illegitimacy of the Authorities. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(1), 25–33

Diemer, M. A., Frisby, M. B., Pinedo, A., Bardelli, E., Elliot, E., Harris, E. … Voight, A. M. (2020). Development of the short critical consciousness scale (Shocritical consciousnessS).Applied Developmental Science,1–17

Diemer, M. A., Pinedo, A., Bañales, J., Mathews, C. J., Frisby, M. B., Harris, E. M., & McAlister, S. (2021). Recentering Action in Critical Consciousness.Child Development Perspectives,15(1),12–17

Dull, B. D., Hoyt, L. T., Grzanka, P. R., & Zeiders, K. H. (2021). Can White Guilt Motivate Action? The Role of Civic Beliefs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(6), 1081–1097

Fernández, J. S., Gaston, J. Y., Nguyen, M., Rovaris, J., Robinson, R. L., & Aguilar, D. N. (2018). Documenting sociopolitical development via participatory action research (PAR) with women of color student activists in the neoliberal university. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 6(2), 591–607

Fine, M., Torre, M. E., Frost, D. M., & Cabana, A. L. (2018). Queer solidarities: New activisms erupting at the intersection of structural precarity and radical misrecognition. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 6(2), 608–630

Fitzgerald, J. C., Cohen, A. K., Castro, M.,E.,&, & Pope, A. (2021). A systematic review of the last decade of civic education research in the United States.Peabody Journal of Education,96(3),235–246

Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. New York, NY: Continuum

Frost, D. M., Fine, M., Torre, M. E., & Cabana, A. (2019). Minority stress, activism, and health in the context of economic precarity: Results from a national participatory action survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and gender non-conforming youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(3–4), 511–526

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness.British journal of social psychology,33(1),1–27

Ginwright, S. A. (2010). Peace out to revolution! Activism among African American youth: An argument for radical healing.Young,18(1),77–96

Ginwright, S. (2015). Hope and healing in urban education: How urban activists and teachers are reclaiming matters of the heart.Routledge

Godfrey, E. B., & Burson, E. (2018). Interrogatingtheintersections:Howintersectionalperspectivescaninformdevelopmentalscholarshiponcriticalconsciousness.Newdirectionsforchildandadolescentdevelopment,2018(161),17–38

Godfrey, E. B., Burson, E. L., Yanisch, T. M., Hughes, D., & Way, N. (2019). A bitter pill to swallow? Patterns of critical consciousness and socioemotional and academic well-being in early adolescence. Developmental psychology, 55(3), 525

Godfrey, E. B., Santos, C. E., & Burson, E. (2019). For better or worse? System-justifying beliefs in sixth‐grade predict trajectories of self‐esteem and behavior across early adolescence. Child development, 90(1), 180–195

Gorski, P. C. (2019). Racial battle fatigue and activist burnout in racial justice activists of color at predominately white colleges and universities.Race ethnicity and education,22(1),1–20

Heberle, A. E., Rapa, L. J., & Farago, F. (2020). Critical consciousness in children and adolescents: A systematic review, critical assessment, and recommendations for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 146(6), 525

Hope, E. C., & Bañales, J. (2019). Black early adolescent critical reflection of inequitable sociopolitical conditions: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Adolescent Research, 34(2), 167–200

Hope, E. C., Cryer-Coupet, Q. R., & Stokes, M. N. (2020). Race-related stress, racial identity, and activism among young Black men: A person-centered approach. Developmental Psychology, 56(8), 1484

Hope, E. C., Hoggard, L. S., & Thomas, A. (2015). Emerging into adulthood in the face of racial discrimination: Physiological, psychological, and sociopolitical consequences for african american youth. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 1(4), 342

Hope, E. C., Velez, G., Offidani-Bertrand, C., Keels, M., & Durkee, M. I. (2018). Political activism and mental health among Black and Latinx college students. Cultural diversity and ethnic minority. Psychology, 24(1), 26–39

Hoyt, L. T., Cohen, A. K., Dull, B., Castro, E. M., & Yazdani, N. (2021). “Constant stress has become the new normal”: Stress and anxiety inequalities among US College students in the time of covid-19. Journal of Adolescent Health,68(2),270–276

Jemal, A. (2017). Critical consciousness: A critique and critical analysis of the literature. The Urban Review, 49(4), 602–626

Karras, J., Maker Castro, E., & Emuka, C. O. (Under Review).Phenomenologically Examining the Sociopolitical Development of Immigrant-Origin Youth During a Season of Social Unrest

Kirshner, B. (2007). Youth activism as a context for learning and development. American Behavioral Scientist, 51(3), 367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764207306065

Klar, M., & Kasser, T. (2009). Some benefits of being an activist: Measuring activism and its role in psychological well-being. Political Psychology, 30(5), 755–777

Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004). Standardqualityassessmentcriteriaforevaluatingprimaryresearchpapersfromavarietyoffields

Lardier, D. T. Jr. (2019). Substance use among urban youth of color: Exploring the role of community-based predictors, ethnic identity, and intrapersonal psychological empowerment. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 91

Lardier, D. T. Jr., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2018). The interacting effects of psychological empowerment and ethnic identity on indicators of well‐being among youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(4), 489–501

Lardier, D. T., Opara, I., Reid, R. J., & Garcia-Reid, P. (2020). The role of empowerment-based protective factors on substance use among youth of color.Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal,1–15

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Gestsdóttir, S. … von Eye, A. (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17–71

Linder, C. (2019). Strategies for supporting student activistsas leaders. New directions for student leadership, 2019(161),89–96

Linder, C., Quaye, S. J., Stewart, T. J., Okello, W. K., & Roberts, R. E. (2019). " The Whole Weight of the World on My Shoulders”: Power, Identity, and Student Activism. Journal of College Student Development, 60(5), 527–542

Madigan, S., Oatley, H., Racine, N., Fearon, R. P., Schumacher, L., Akbari, E. … Tarabulsy, G. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of maternal prenatal depression and anxiety on child socioemotional development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(9), 645–657

Maker Castro, E., Dull, B., Hoyt, L. T., & Cohen, A. K. (2022). Associations between critical consciousness and well-being in a national sample of college students during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(2), 760–777

Miller, J. W., Naimi, T. S., Brewer, R. D., & Jones, S. E. (2007). Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics, 119(1), 76–85

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Altman, D., & Antes, G.,etal (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Montague, A. C., & Eiroa-Orosa, F. J. (2018). In it together: Exploring how belonging to a youth activist group enhances well‐being. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1), 23–43

Nesi, J. (2020). The impact of social media on youth mental health: challenges and opportunities.North Carolina medical journal,81(2),116–121

Opara, I., Rodas, E. I. R., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2020). Ethnic identity, empowerment, social support and sexual risk behaviors among black adolescent girls: examining drug use as a mediator.Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal,1–16

Opara, I., Rodas, E. I. R., Lardier, D. T., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2020). Validation of the abbreviated socio-political control scale for youth (SPCS-Y) among urban girls of color. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(1), 83–95

Ozer, E. J., & Schotland, M. (2011). Psychological empowerment among urban youth: Measure development and relationship to psychosocial functioning. Health Education & Behavior, 38(4), 348–356

Pedrelli, P., Nyer, M., Yeung, A., Zulauf, C., & Wilens, T. (2015). College students: mental health problems and treatment considerations. Academic Psychiatry, 39(5), 503–511

Peterson, N. A., Peterson, C. H., Agre, L., Christens, B. D., & Morton, C. M. (2011). Measuring youth empowerment: Validation of a sociopolitical control scale for youth in an urban community context. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(5), 592–605

Pinedo, A., Durkee, M. I., Diemer, M. A., & Hope, E. C. (2021). DisentanglinglongitudinaltrajectoriesofracialdiscriminationandcriticalactionamongBlackandLatinxcollegestudents:Whatroledopeersplay?.Cultural diversity and ethnic minority psychology

Poteat, V. P., Godfrey, E. B., Brion-Meisels, G., & Calzo, J. P. (2020). Development of youth advocacy and sociopolitical efficacy as dimensions of critical consciousness within gender-sexuality alliances. Developmental psychology, 56(6), 1207

Rapa, L. J., Bolding, C. W., & Jamil, F. M. (2020). Development and initial validation of the short critical consciousness scale (critical consciousnessS-S).Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,70,101164

Rapa, L. J., & Geldhof, G. J. (2020). Critical consciousness: New directions for understanding its development during adolescence.Journal of applied developmental psychology,70,101187

Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology.American journal of community psychology,15(2),121–148

Renn, K. A., & Ozaki, C. C. (2010). Psychosocial and leadership identities among leaders of identity-based campus organizations. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 3(1), 14

Rew, L., & Horner, S. D. (2003). Youth resilience framework for reducing health-risk behaviors in adolescents. Journal of pediatric nursing, 18(6), 379–388

Russell, S. T., Muraco, A., Subramaniam, A., & Laub, C. (2009). Youth empowerment and high school gay-straight alliances. Journal of youth and adolescence, 38(7), 891–903

Saxena, P., Dubey, A., & Pandey, R. (2011). Role of Emotion Regulation Difficulties in Predicting Mental Health and Well-being.SIS Journal of Projective Psychology & Mental Health,18(2)

Saylor, C. (2004). The circle of health: a health definition model. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 22(2), 97–115

Seider, S., & Graves, D. (2020). Schooling for Critical Consciousness: Engaging Black and Latinx Youth in Analyzing, Navigating, and Challenging Racial Injustice.Harvard Education Press

Smith, A. (2016). 6 Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy.InColor of Violence(pp.66–73).Duke University Press

Stone, L. (2021). Youth power—youth movements: myth, activism, and democracy.Ethics and Education,16(2),249–261

Sulé, V. T., Nelson, M., & Williams, T. (2021). They# Woke: How Black Students in an After-School Community-Based Program Manifest Critical Consciousness. Teachers College Record, 123(1), 1–38

Suárez-Orozco, C., Motti-Stefanidi, F., Marks, A., & Katsiaficas, D. (2018). An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth.American Psychologist,73(6),781

Tyler, C. P., Geldhof, G. J., Black, K. L., & Bowers, E. P. (2019). Critical reflection and positive youth development among white and Black adolescents: Is understanding inequality connected to thriving?.Journal of youth and adolescence,1–15

Tyler, C. P., Olsen, S. G., Geldhof, G. J., & Bowers, E. P. (2020). Critical consciousness in late adolescence: Understanding if, how, and why youth act.Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,70,101165

Uriostegui, M., Roy, A. L., & Li-Grining, C. P. (2021). What Drives You? Black and Latinx Youth’s Critical Consciousness, Motivations, and Academic and Career Activities. Journal of youth and adolescence, 50(1), 58–74

Vaccaro, A., & Mena, J. A. (2011). It’snotburnout,it’smore:Queercollegeactivistsofcolorandmentalhealth.JournalofGay&LesbianMentalHealth,15(4),339–367.Chicago