Abstract

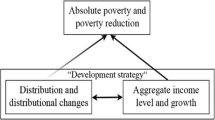

The paper offers a new country classification system defined in relative terms and jointly based on the level and the medium–long term rate of growth of per capita income. The classification system identifies four categories of economies: poor (low income–low growth), emerging (low income–high growth), booming (high income–high growth) and affluent (high income–low growth). After classifying 122 countries in periods 1985–1999 and 2000–2014, the paper focuses on the comparison of poor and emerging economies and, in parallel, of emerging and high-income economies, and characterizes their transitions across categories. In line with the empirical literature on economic growth, the results of multinomial logit analysis suggest that higher growth rates of export and investment are the main factors distinguishing emerging from poor economies. Further, a better institutional setting, measured by various dimensions of economic freedom, plays an important role in driving the transition of low income countries from low to high growth. Moreover, along with a better technological advancement, it also represents the crucial attribute differentiating high-income from emerging economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Vaggi (2017, p. 64–65) notices “the original thresholds were meant to provide a comparative classification of countries and were supposedly considered as being relative thresholds […]. However, the annual adjustment of the thresholds is based only on “international inflation”, which leads to the fact that the thresholds are rather ‘sticky’; they become similar to absolute thresholds and provide a partial view of the changes in the global economic scenario.”

In the World Economic Outlook, the IMF classifies the world into two groups—advanced economies and emerging market and developing economies—according to per capita income level, export diversification and the degree of integration into the global financial system.

The average per capita income of country i (i = 1,…,n) over period T (T = 1,….,t) is calculated as \(\bar{y}_{i,T} = \frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{T = 1}^{t} y_{i,T} }}{t}\), while the average annual rate of growth of country i’s per capita income is given by \(\bar{r}_{i.T} = \left( {\sqrt[{t - 1}]{{\frac{{y_{i,t} }}{{y_{i,1} }}}} - 1} \right) \times 100\).

An alternative way of determining the two thresholds is to weight countries’ per capita income by their share of world population in the computation of \(\bar{y}_{T}\), that corresponds to calculate the individual world average income and its rate of growth. In this case, the benchmark would not be the average economy but rather the average individual at a world level. Even if it is a common approach adopted by many studies about global income inequality and poverty (Deaglio 1994, 2004; Milanovic 2013), it does not match our focus, that is to evaluate each country’s economic conditions against an average condition. Another alternative way would be to select as a benchmark the median economy. However, Nielsen (2011) formally demonstrates that using the mean outcome as the threshold value dividing countries into two categories is the most appropriate choice, since it minimizes the error associated to treating all countries belonging to the same category as alike. Moreover, it is interesting to note that both the median economy and the average individual methods, applied to periods 1985–1999 and 2000–2014, get thresholds of per capita income close to the cut-off level used by the World Bank in order to divide high-income countries from low and middle-income countries, that has been highly criticized for undervaluing the number of low income countries (to this purpose, see Vaggi 2017).

The concept of emerging markets, introduced in 1981 by economists at the International Finance Corporation (WB Group), has been largely defined by global institutions as well as financial companies and is mainly based on countries’ financial structure.

In both periods, the percentage of countries clustered around the averages (with a deviation lower than 10%) was below one-tenth and only one country had a ‘light’ membership in terms of both income and rate of growth (Malaysia in 2000–2014).

Our calculations based on the Total Economy Database, Conference Board.

Estonia, Korea, Malaysia, Slovak Republic, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Unfortunately, we cannot consider booming and affluent economies—i.e. the two high income economies- as two different outcomes because the number of countries in these categories is limited. In particular, in period 1985–1999 our sample counts only ten economies classified as affluent, while for period 2000–2014 booming economies are just 9. We then merge the two categories and consider them as one single group.

In order to identify the model, a reference outcome j must be arbitrarily selected and the respective coefficients \(\beta_{j}\) must be set equal to 0.

The same hypothesis can be tested through a Wald test, that however turns out to be less reliable for small samples, as in our case (Agresti 2007).

The two additional observations for period 2000–2014 correspond to Ethiopia and Tajikistan.

For each of the independent variables, the LR test is performed as follows. First, the full model is estimated. Second, a reduced model that excludes the tested variable is estimated. The difference in the LR2 is then computed and used to test the hypothesis that the tested variable does not affect the outcome (Freese and Long 2000).

When the beginning-of-period value is not available, we use the first non-missing value over the first 5 years of the fifteen-year period.

More easily, it may also be a reflection of the sample composition by category.

When a proxy for technological advancement is added to the full model by ignoring the rule of ten observations per regressor (necessary to guarantee the empirical validity in multinomial logit models), predictably some coefficients lose their significance (even if the most part of them maintains the same sign and size) and this is very likely due to the violation of the rule and the subsequent lack of validity, while the coefficient of technological advancement is never significant in the two periods.

We also use a dummy variable indicating whether the country is landlocked, but the coefficient is not significant.

The WVS also provides a series of detailed data on religion and religiousness that, although more refined than the variables here used, can not be exploited in our analysis because of the significant drop in the number of observations.

Guiso et al. (2003) showed that religious denominations are strictly related to trust, whose level increases if a person is Catholic or Protestant.

If we look at the mean level of the variables, in both periods they were characterized by a higher fertility rate, a lower educational attainment of people aged 20–24, a higher Gini index and a lower share of urban population.

The fourth Asian Tiger, South Korea, was a booming economy in the second period but in the first period it was classified as emerging.

This is of course an average relation, that does not capture single cases of huge inequalities like experienced by China and India during their process of emergence.

References

Agresti, A. (2007). An introduction to categorical data analysis (2nd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Arnold, D. J., & Quelch, J. A. (1998). New strategies in emerging markets. Sloan Management Review,40(1), 7–20.

Barba Navaretti, G., & Tarr, D. G. (2000). International knowledge flows and economic performance: An introductory survey. World Bank Economic Review,14(1), 1–15.

Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,106(2), 407–443.

Barro, R. J. (2000). Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. Journal of Economic Growth,5(1), 5–32.

Barro, R. J. (2013). Education and economic growth. Annals of Economics and Finance,14(2), 301–328.

Barro, R. J., & Lee, J. W. (2013). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics,104, 184–198.

Bassanini, A., & Scarpetta, S. (2001). The driving forces of economic growth: panel data evidence for the OECD countries. OECD Economic Studies,33, 9–56.

Birdsall, M., Campos, L., Kim, C., Corden, W. M., MacDonald, L., Pack, H., et al. (1993). The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy. World Bank policy research report. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., Fink, G., & Finlay, J. (2009). Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend. Journal of Economic Growth,14(2), 79–101.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., Hu, L., Liu, Y., Mahal, A., & Yip, W. (2010). The contribution of population health and demographic change to economic growth in China and India. Journal of Comparative Economics,38(1), 17–33.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Sevilla, J. (2003). The demographic dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Bloom, D. E., & Williamson, J. G. (1998). Demographic transitions and economic miracles in emerging Asia. The World Bank Economic Review,12(3), 419–455.

Bulman, D., Eden, M., & Nguyen, H. (2014), Transitioning from low-income growth to high-income growth: Is there a middle-income trap? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 7104.

Byrne, J. (2010). Output collapse, growth and volatility in Sub-Saharan Africa: A regime-switching approach. Economic and Social Review,41(1), 21–41.

Choudhry, M. T., & Elhorst, J. P. (2010). Demographic transition and economic growth in China, India and Pakistan. Economic Systems,34(3), 218–236.

Collier, P. (2007). The Bottom Billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Deaglio, M. (1994), Il mondo tra povertà e sviluppo, Rivista di Politica Economica, febbraio 1994.

Deaglio, M. (2004). Convergenza e divergenza mondiale nella speranza di vita alla nascita—1960–99. Andamenti di lungo periodo alla luce della globalizzazione. In B. Jossa (Ed.), Il futuro del capitalismo (pp. 159–170). Bologna: Il Mulino, Collana della Società degli Economisti.

Delgado, M. S., Henderson, D. J., & Parmeter, C. F. (2014). Does education matter for economic growth? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics,76(3), 334–359.

Easterly, W. (2006). Reliving the 1950s: The big push, poverty traps, and takeoffs in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth,11(4), 289–318.

Fantom, N., & Serajuddin, U. (2016). The world bank classification of countries by income. Policy Research Working Paper, No. 7528, The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Freese, J., & Long, J. S. (2000). Tests for the multinomial logit model. Stata Technical Bulletin,58, 19–25.

Gill, I., & Kharas, H. (2007). An East asian renaissance: Ideas for economic growth. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2003). People's opium? Religion and economic attitudes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 225–282.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2006). Does culture affect economic outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives,20, 23–48.

Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics,114(1), 83–116.

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. The Academy of Management Journal,43(3), 249–267.

Hosmer, D., Lemeshow, S., & Sturdivant, R. (2013). Applied logistic regression (3rd ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Inglehart, R. C., Haerpfer, A., Moreno, C., Welzel, K., Kizilova, J., Diez-Medrano, M., Lagos, P., Norris, E., et al. (eds.) (2018). World values survey: all rounds—Country-pooled datafile version. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWVL.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

Jain, C. S. (2006). Emerging economies and the transformation of international business. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Jerzmanowski, M. (2006). Empirics of Hills, plateaus, mountains and plains: A Markov-switching approach to growth. Journal of Development Economics,81(2), 357–385.

Jones, C. I. (2016). The facts of economic growth. In J. B. Taylor & H. Uhlig (Eds.), Handbook of macroeconomics (Vol. 2, pp. 3–69). Amsterdam: North Holland.

Jones, B. F., & Olken, B. A. (2008). The anatomy of start-stop growth. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 582–587.

Kerekes, M. (2012). Growth miracles and failures in a Markov switching classification model of growth. Journal of Development Economics,98(2), 167–177.

Khan, M. M., Mahmood, A., But, I., & Akram, S. (2015). Cultural values and economic development: A review and assessment of recent studies. Journal of Culture, Society and Development,9, 60–70.

Kraay, A., & McKenzie, D. (2014). Do poverty traps exist? Assessing the evidence. Journal of Economic Perspectives,28(3), 127–148.

Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. The American Economic Review,45(1), 1–28.

Lamperti, F., & Mattei, C. E. (2018). Going up and down: rethinking the empirics of growth in the developing and newly industrialized world. Journal of Evolutionary Economics,28(4), 749–784.

Larson, G., Loayza, N., & Woolcock, M. (2016). The middle-income trap: Myth or reality? Research Policy Brief, The World Bank Malaysia Hub, No. 1, March.

Long, J. S., & Freese, J. (2014). Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata (3rd ed.). College Station: Stata Press.

Milanovic, B. (2013). Global income inequality by the numbers: in history and now. Global Policy,4(2), 198–208.

Nielsen, L. (2011). Classifications of countries based on their level of development: How it is done and how it could be done. IMF Working Paper, WP/11/31.

Pritchett, L. (2000). Understanding patterns of economic growth: Searching for hills among plateaus, mountains, and plains. The World Bank Economic Review,14(2), 221–250.

Saccone, D. (2017). Economic growth in emerging economies: What, who and why. Applied Economics Letters,24(11), 800–803.

Schwab, J. A. (2002). Multinomial logistic regression: basic relationships and complete problems. http://www.utexas.edu/courses/schwab/sw388r7/SolvingProblems/.

Tezanos Vàzquez, S., & Sumner, A. (2013). Revisiting the meaning of development: A multidimensional taxonomy of developing countries. The Journal of Development Studies,49(12), 1728–1745.

Tezanos Vàzquez, S., & Sumner, A. (2016). Is the ‘developing world’ changing? A dynamic and multidimensional taxonomy of developing countries. The European Journal of Development Research,28(5), 847–874.

The Boao Forum for Asia. (2009). The development of emerging economies. Beijing: University of International Business and Economics Press.

UNCTAD. (1996). Trade and development report. Geneva: United Nations.

Vaggi, G. (2017). The rich and the poor: A note on countries’ classification. PSL Quarterly Review,70(279), 59–82.

Vercueil, J. (2012). Les pays émergents. Brésil–Russie–Inde–Chine. Mutations économiques et nouveaux défis. Paris: Bréal.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Turin Centre on Emerging Economies (OEET) and, in particular, Professor Vittorio Valli for their stimulating discussions and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix I: List of indicators and sources

Age dependency ratio, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Agricultural raw materials exports (% of merchandise exports), World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Conflicts, Polity IV Project, Center for Systemic Peace.

Educational attainment (15 + and 20–24), Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Data, Barro and Lee (2013).

Export and import growth rates, our calculations on World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Exports and imports as a percentage of GDP, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

FDI as a percentage of GDP, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

FDI growth rates, our calculations on World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Fertility rate, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Fiscal balance, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Geographical variables, GeoDist, CEPII.

Gini index, Global Income Dataset, Global Consumption and Income Project (GCIP).

Illiteracy rate, Barro-Lee Educational Attainment Data, Barro and Lee (2013).

Income share of top 1 %, Global Income Dataset, Global Consumption and Income Project (GCIP).

Index of economic freedom, Economic Freedom of the World, Fraser Institute.

Inflation, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Investment as a percentage of GDP, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Investment growth rates, our calculations on World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Percentage of urban population, World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Political regime, Polity IV Project, Center for Systemic Peace.

Real GDP per capita with EKS PPP, Total Economy Database, Conference Board.

Religious diversity index and dominant religions, Pew Research Center.

Researchers in R&D (per million people), World Development Indicators, World Bank.

R&D expenditure (% GDP), World Development Indicators, World Bank.

Appendix II: Country membership by period and transition matrix

2.1 Country membership by period

Country | 1985–1999 | Level of membership stability | 2000–2014 | Level of membership stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Albania | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Algeria | Poor | Stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Angola | Poor | Unstable | Emerging | Stable |

Argentina | Emerging | Unstable | Poor | Stable |

Armenia | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Australia | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Austria | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Azerbaijan | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Bahrain | Affluent | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Bangladesh | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Barbados | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Stable |

Belarus | Poor | Unstable | Emerging | Stable |

Belgium | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Bolivia | Emerging | Unstable | Poor | Unstable |

Bosnia and Herzegovina | n.a. | Unstable | Poor | Unstable |

Brazil | Poor | Nearly stable | Poor | Stable |

Bulgaria | Poor | Stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Burkina Faso | Emerging | Stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Cambodia | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Cameroon | Poor | Stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Canada | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Chile | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

China | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Colombia | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Congo, Dem. Rep. | Poor | Stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Costa Rica | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Unstable |

Cote d’Ivoire | Poor | Nearly stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Croatia | Affluent | Unstable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Cyprus | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Czech Republic | Booming | Unstable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

Denmark | Booming | Unstable | Affluent | Stable |

Dominican Republic | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Ecuador | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Egypt, Arab Rep. | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Estonia | Emerging | Unstable | Booming | Nearly stable |

Ethiopia | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Finland | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

France | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Georgia | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Germany | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Ghana | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Greece | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

Guatemala | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Stable |

Hong Kong SAR, China | Booming | Nearly stable | Booming | Nearly stable |

Hungary | Affluent | Unstable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

Iceland | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

India | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Indonesia | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Iran, Islamic Rep. | Poor | Unstable | Poor | Unstable |

Iraq | Poor | Unstable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Ireland | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

Israel | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Italy | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Jamaica | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Stable |

Japan | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Jordan | Poor | Nearly stable | Poor | Unstable |

Kazakhstan | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Kenya | Poor | Nearly stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Korea, Rep. | Emerging | Nearly stable | Booming | Stable |

Kuwait | Affluent | Unstable | Affluent | Unstable |

Kyrgyz Republic | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Latvia | Poor | Unstable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Lithuania | Poor | Unstable | Emerging | Unstable |

Luxembourg | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Macedonia, FYR | Poor | Stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Madagascar | Poor | Stable | Poor | Stable |

Malawi | Poor | Unstable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Malaysia | Emerging | Nearly stable | Booming | Unstable |

Mali | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Malta | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

Mexico | Emerging | Unstable | Poor | Stable |

Moldova | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Morocco | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Mozambique | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Myanmar | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Netherlands | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

New Zealand | Booming | Unstable | Affluent | Stable |

Niger | Poor | Stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Nigeria | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Norway | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Oman | Booming | Unstable | Affluent | Unstable |

Pakistan | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Peru | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Philippines | Emerging | Unstable | Emerging | Unstable |

Poland | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Unstable |

Portugal | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Qatar | Affluent | Unstable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

Romania | Poor | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Russian Federation | Affluent | Nearly stable | Booming | Nearly stable |

Saudi Arabia | Affluent | Nearly stable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

Senegal | Poor | Nearly stable | Poor | Stable |

Serbia and Montenegro | Poor | Stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Singapore | Booming | Nearly stable | Booming | Unstable |

Slovak Republic | Emerging | Nearly stable | Booming | Unstable |

Slovenia | Affluent | Nearly stable | Affluent | Nearly stable |

South Africa | Poor | Stable | Poor | Stable |

Spain | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Sri Lanka | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

St. Lucia | Emerging | Stable | Poor | Stable |

Sudan | Emerging | Unstable | Poor | Unstable |

Sweden | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Switzerland | Booming | Nearly stable | Affluent | Stable |

Taiwan, China | Booming | Nearly stable | Booming | Unstable |

Tajikistan | Poor | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Tanzania | Poor | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Thailand | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Trinidad and Tobago | Emerging | Nearly stable | Booming | Nearly stable |

Tunisia | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Unstable |

Turkey | Emerging | Nearly stable | Poor | Unstable |

Turkmenistan | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Stable |

Uganda | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Ukraine | Poor | Nearly stable | Emerging | Unstable |

United Arab Emirates | Affluent | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

United Kingdom | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

United States | Booming | Stable | Affluent | Stable |

Uruguay | Emerging | Nearly stable | Emerging | Nearly stable |

Uzbekistan | Poor | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Venezuela, RB | Affluent | Unstable | Poor | Nearly stable |

Vietnam | Emerging | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Yemen, Rep. | Emerging | Unstable | Poor | Stable |

Zambia | Poor | Stable | Emerging | Stable |

Zimbabwe | Poor | Nearly stable | Poor | Nearly stable |

2.2 Transition matrix

2000–2014 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Poverty | Emergence | Boom | Affluence | Total | |

1985–1999 | |||||

Poverty | 15 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 38 |

Probability | 39.5 | 60.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 |

Emergence | 16 | 22 | 5 | 0 | 43 |

Probability | 37.2 | 51.2 | 11.6 | 0.0 | 100 |

Boom | 0 | 0 | 3 | 28 | 31 |

Probability | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.7 | 90.3 | 100 |

Affluence | 2 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 10 |

Probability | 20.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 70.0 | 100 |

Total | 33 | 45 | 9 | 35 | 122 |

Appendix III: Classification of economies by region

1985–1999 | 2000–2014 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

n | % | n | % | |

Poor economies | ||||

East Asia and Pacific | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Europe and Central Asia | 17 | 44.7 | 4 | 12.1 |

LAC | 3 | 7.9 | 9 | 27.3 |

MENA | 4 | 10.5 | 6 | 18.2 |

North America | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

South Asia | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.0 |

Sub Saharan Africa | 14 | 36.8 | 13 | 39.4 |

Total | 38 | 100.0 | 33 | 100.0 |

Emerging economies | ||||

East Asia and Pacific | 9 | 20.9 | 7 | 15.6 |

Europe and Central Asia | 6 | 14.0 | 18 | 40.0 |

LAC | 13 | 30.2 | 7 | 15.6 |

MENA | 4 | 9.3 | 2 | 4.4 |

North America | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

South Asia | 4 | 9.3 | 3 | 6.7 |

Sub Saharan Africa | 7 | 16.3 | 8 | 17.8 |

Total | 43 | 100.0 | 45 | 100.0 |

Booming economies | ||||

East Asia and Pacific | 6 | 19.4 | 5 | 55.6 |

Europe and Central Asia | 20 | 64.5 | 3 | 33.3 |

LAC | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 11.1 |

MENA | 3 | 9.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

North America | 2 | 6.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

South Asia | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Sub Saharan Africa | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Total | 31 | 100.0 | 9 | 100.0 |

Affluent economies | ||||

East Asia and Pacific | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 8.6 |

Europe and Central Asia | 4 | 40.0 | 22 | 62.9 |

LAC | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

MENA | 5 | 50.0 | 8 | 22.9 |

North America | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 5.7 |

South Asia | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Sub Saharan Africa | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Total | 10 | 100.0 | 35 | 100.0 |

Appendix IV: Likelihood-ratio tests on independent variables

4.1 Period 1985–1999

Chi2 | P > Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|

Age dependency ratio | 4.494 | 0.106 |

Export growth | 4.930 | 0.085 |

Investment growth | 3.247 | 0.197 |

Urban population % | 9.409 | 0.009 |

Inflation | 0.731 | 0.694 |

Gini | 1.383 | 0.501 |

Illiteracy rate | 0.405 | 0.817 |

Economic freedom index | 6.236 | 0.044 |

4.2 Period 2000–2014

Chi2 | P > Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|

Age dependency ratio | 23.004 | 0.000 |

Export growth | 19.980 | 0.000 |

Investment growth | 15.823 | 0.000 |

Urban population % | 14.483 | 0.001 |

Inflation | 3.440 | 0.179 |

Gini | 16.429 | 0.000 |

Illiteracy rate | 4.496 | 0.106 |

Economic freedom index | 9.146 | 0.010 |

Appendix V: Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values

5.1 Period 1985–1999

Full model (column 3) | Reduced model (column 4) | |

|---|---|---|

AIC | 1.536 | 1.528 |

BIC | − 210.528 | − 235.834 |

BIC′ | − 16.520 | − 41.826 |

5.2 Period 2000–2014

Full model (column 3) | Reduced model (column 4) | |

|---|---|---|

AIC | 0.959 | 0.968 |

BIC | − 260.724 | − 269.786 |

BIC′ | − 69.014 | − 78.076 |

Appendix VI: Sensitivity analysis

6.1 Period 1985–1999

(1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Poor economies | |||||||||

Demography | 1.0289*** | 0.0325* | |||||||

Economic openness | − 0.1386* | − 0.1632* | − 0.2267** | − 0.1757** | − 0.1585* | − 0.3222** | − 0.1411* | − 0.0129 | − 0.1169 |

Physical capital accum. | |||||||||

Structural change | 0.0048 | 0.0311 | 0.0103 | − 0.0762 | 0.0211 | 0.0168 | 0.0032 | 0.0427 | 0.0151 |

Macroeconomic policy | − 0.0603 | ||||||||

Inequality | 0.1052* | ||||||||

Human capital | − 0.0395 | ||||||||

Institutional quality | − 0.2854 | − 0.3851 | − 0.1556 | − 0.2898 | − 0.6086 | − 0.2670 | − 0.3416 | 0.0613 | |

Latitude | 0.1893 | ||||||||

Technological advancement | 0.2021 | 0.0001 | |||||||

Booming and affluent economies | |||||||||

Demography | − 2.6895*** | − 0.1264*** | |||||||

Economic openness | 0.0178 | 0.0671 | − 0.1024 | − 0.0364 | 0.0370 | − 0.0282 | − 0.0003 | 0.0164 | − 0.0467 |

Physical capital accumulation | |||||||||

Structural change | 0.0898*** | 0.1011*** | 0.0885*** | − 0.1745* | 0.0844*** | 0.0905*** | 0.0695*** | 0.0623* | 0.0438 |

Macroeconomic policy | − 0.3817* | ||||||||

Inequality | − 0.2419* | ||||||||

Human capital | 0.0788 | ||||||||

Institutional quality | 1.1050*** | 1.0320*** | 1.4613*** | 1.2061*** | 1.5032** | 1.1004** | 0.7732 | 1.1085** | |

Latitude | 5.4802* | ||||||||

Technological advancement | 2.1338** | 0.0013*** | |||||||

Obs. | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 70 | 87 | 60 | 55 |

6.2 Period 2000–2014

(1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Poor economies | ||||||||

Demography | 0.1498*** | 2.0025*** | 0.1239*** | 0.1422*** | 0.1974** | 0.1917* | 0.2236** | 0.2395** |

Economic openness | − 0.2517 | − 0.2441 | − 0.0377 | − 0.0050 | − 0.4175* | − 0.3281 | − 0.0108 | − 0.3579° |

Physical capital accumulation | − 0.4806*** | − 0.6974*** | − 0.4807*** | − 0.4517*** | − 0.7892*** | − 0.5035** | − 1.2080*** | − 0.4311** |

Structural change | 0.0593* | 0.0721** | 0.0535* | 0.0475* | 0.1004** | 0.0627* | 0.0991* | 0.1111* |

Inequality | 0.0960 | 0.0993 | 0.1199 | − 0.0366 | 0.0139 | 13.6398 | 9.6998 | |

Human capital | 0.1141 | |||||||

Institutional quality | − 1.3047° | − 1.4680* | − 1.2194 | − 1.0345° | − 0.7775 | − 1.4534° | − 1.7985° | − 1.3649* |

Latitude | 6.0869 | |||||||

Technological advancement | 1.8248 | 0.0021 | ||||||

Booming and affluent economies | ||||||||

Demography | − 0.3157* | − 1.3439 | − 0.2509* | − 0.2399 | − 1.1965* | − 0.5526* | − 0.3397 | 4.8682 |

Economic openness | − 1.1959** | − 0.8520*** | − 0.4778*** | 0.1534* | − 3.1321* | − 1.3200* | − 1.6038** | − 22.5280 |

Physical capital accumulation | 0.1046 | − 0.0531 | − 0.0824 | 0.6036** | − 0.3900 | 0.2104 | − 0.2632 | − 6.2078 |

Structural change | 0.0699* | 0.0597* | 0.0656* | 0.1109** | 0.1917* | 0.1478* | 0.0471 | 2.7244 |

Inequality | − 0.2908* | − 0.2346* | − 0.1216 | − 0.0292* | − 0.0486* | − 33.6174° | − 426.6601 | |

Human capital | 1.1999** | |||||||

Institutional quality | 3.2408** | 2.2720** | 2.3375** | 2.4083** | 8.1259* | 3.3499* | 4.1343** | 38.3601 |

Latitude | − 12.5449 | |||||||

Technological advancement | 2.8668 | 0.0847 | ||||||

Obs. | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 87 | 79 | 79 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saccone, D., Deaglio, M. Poverty, emergence, boom and affluence: a new classification of economies. Econ Polit 37, 267–306 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-019-00166-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-019-00166-4

Keywords

- Country classification systems

- Per capita income

- Economic growth

- Emerging economies

- Comparative economics