Abstract

The famous linguistic-savings hypothesis states that languages that grammatically separate the future from the present (like English) causally induce less future-oriented behavior than languages in which speakers can refer to the future using present tense (like German or Chinese). Chen et al., European Economic Review 120 (2019) experimentally investigate the effect of using future-oriented language on incentivized intertemporal choices and find no support for the hypothesis. We replicate Chen et al., European Economic Review 120 (2019)’s study in the German-speaking context. In our experiment with 332 subjects, we randomly refer to future payments using present or future tense and find no causal effect of language on intertemporal choice. Given the importance of replications for confidence in scientific findings, our results provide corroborating evidence that the linguistic-savings hypothesis is not empirically tenable. Eventually, the results provide a methodological contribution to the conduct of experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material

The data are available upon request.

Code availability

STATA code is available upon request.

Notes

See Chen (2013) for the classification of languages into s-FTR and w-FTR.

The notion that language structure can affect thought and behavior is commonly called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (Whorf 1956). While it has waxed and waned, there is plenty of evidence that language can have an impact on thoughts and behavior. See, e.g., Boroditsky (2001) on the (horizontal or vertical) conceptions of time of Mandarin and English speakers, Winawer et al. (2007) on color discrimination, Danziger and Ward (2010) on associations between ethnic groups, Costa et al. (2014) on moral judgement and behavior and foreign vs. native languages or Bernhofer et al. (2021) on attitudes towards uncertainty and risky behavior.

A related strand of research investigates the ancestral roots of time preferences and language structure. Exploiting a natural experiment associated with the historic expansion of land productivity, Galor and Özak (2016) show that geographical variation in land productivity is associated with long-term orientation today. Closer to our study, Galor et al. (2017) provide supporting empirical evidence that higher pre-industrial crop yields may have led to increased use of periphrastic future tense (similar to w-FTR). Furthermore, they conduct country-level regressions of different measures of today’s societies’ long-term orientation on (i) the share of speakers of languages with periphrastic future tense use, and (ii) pre-industrial crop return. They find positive coefficients on both variables, though the magnitude and significance of the coefficient on periphrastic future tense varies across specifications.

Of course, the policy implications of these two possible explanations are very different: If the former is true, policy-makers could aim to increase patience in individuals through deliberate language use (i.e. using present tense when asking for important decisions whenever possible), and thus rake in the societal benefits of patient behavior which have been well documented in previous research (e.g., Castillo et al., 2011; Golsteyn et al., 2014; Mischel et al., 1989; Moffitt et al., 2011; Sutter et al., 2013). Such strategies are, of course, unwarranted if the latter explanation is true.

See the Online Supplement for the experimental instructions.

Levitt and List (2009) discuss three levels at which replication can operate. The first one concerns reanalyzing the original data, the second one represents the conduction of an experiment with new subjects but using a similar protocol as the original experiment and the third one is characterized by a new research design which tests the same hypothesis as the first study. We argue that in the latter case a successful replication of the original results gives the strongest signal for a robust outcome. See, e.g., Maniadis et al. (2014) and Maniadis and Tufano (2017) for discussions on the importance of replications for the advancement of science.

Note that German serves as a perfect example for an unambiguously w-FTR language according to Chen (2013). Also, German is the most frequently spoken w-FTR language in Western societies and the third most frequently spoken w-FTR language in the world after Mandarin-Chinese and Indonesian (see the 2020 list of the top 200 most spoken languages of The Ethnologue 200, SIL International, 2020).

Inconsistent choice patterns arise if subjects switch more than once along the list. In our sample, only 1 subject chose inconsistently. When excluding this subject from the analysis all the results remain unchanged.

When restricting the sample to those who speak German as the only mother language the importance of thrift to oneself is no longer significant (see Table S4 in the Online Supplement).

One other possible explanation of our null result might be that German speakers are simply used to using both present and future tense when referring to the future, and are, therefore, immune to our treatment variation. Interestingly, using online weather forecasts, Chen (2013) classifies German as a language that mostly uses the present when referring to future events, suggesting that exposure to both forms of future-time reference is not more common in German than in other w-FTR languages. We consider applying our experimental design to languages with varying frequency of present versus future-tense usage an interesting avenue for future research.

References

Alesina, A., & Ferrara, E. L. (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic performance. Journal of Economic Literature, 43(3), 762–800. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205105774431243

Bernhofer, J., Costantini, F., Kovacic, M. (2021). Risk Attitudes Investment Behavior and Linguistic Variation. Journal of Human Resources. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.59.2.0119-9999R2

Boroditsky, L. (2001). Does language shape thought?: Mandarin and English speakers’ conceptions of time. Cognitive Psychology, 43(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.2001.0748

Burks, S. V., Carpenter, J. P., Goette, L., & Rustichini, A. (2009). Cognitive skills affect economic preferences, strategic behavior, and job attachment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(19), 7745–7750. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0812360106

Castillo, M., Ferraro, P. J., Jordan, J. L., & Petrie, R. (2011). The today and tomorrow of kids: Time preferences and educational outcomes of children. Journal of Public Economics, 95(11–12), 1377–1385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.07.009

Chen, J. I., He, T.-S., & Riyanto, Y. E. (2019). The effect of language on economic behavior: Examining the causal link between future tense and time preference in the lab. European Economic Review, 120, 103307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.103307

Chen, M. K. (2013). The effect of language on economic behavior: Evidence from savings rates, health behaviors, and retirement assets. American Economic Review, 103(2), 690–731. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.2.690

Chen, S., Cronqvist, H., Ni, S., & Zhang, F. (2017). Languages and corporate savings behavior. Journal of Corporate Finance, 46, 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.07.009

Chi, J. D., Su, X., Tang, Y., & Xu, B. (2020). Is language an economic institution? Evidence from R&D investment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 62, 101578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101578

Costa, A., Foucart, A., Hayakawa, S., Aparici, M., Apesteguia, J., Heafner, J., et al. (2014). Your morals depend on language. PLoS One, 9(4), e94842. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094842

Danziger, S., & Ward, R. (2010). Language changes implicit associations between ethnic groups and evaluation in bilinguals. Psychological Science 21(6), 799–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610371344

Desmet, K., Ortuño-Ortín, I., & Wacziarg, R. (2012). The political economy of linguistic cleavages. Journal of Development Economics, 97(2), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2011.02.003

Desmet, K., Weber, S., & Ortuño-Ortín, I. (2009). Linguistic diversity and redistribution. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(6), 1291–1318. https://doi.org/10.1162/JEEA.2009.7.6.1291

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2010). Are risk aversion and impatience related to cognitive ability? American Economic Review, 100(3), 1238–1260. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.3.1238

Falk, A., Becker, A., Dohmen, T., Enke, B., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2018). Global evidence on economic preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(4), 1645–1692. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy013

Fasan, M., Gotti, G., Kang, T., & Liu, Y. (2016). Language FTR and earnings management: International evidence. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2763922 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2763922

Fearon, J. D. (2003). Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth, 8(2), 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024419522867

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-006-9159-4

Galor, O., Özak, Ö., & Sarid, A. (2017). Geographic origins and economic consequences of language structures. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2820889 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2820889.

Galor, O., & Özak, Ö. (2016). The agricultural origins of time preference. American Economic Review, 106(10), 3064–3103. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150020

Golsteyn, B. H. H., Grönqvist, H., & Lindahl, L. (2014). Adolescent time preferences predict lifetime outcomes. The Economic Journal, 124(580), F739–F761. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12095

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-015-0004-4

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802762024700

Kerschbamer, R. (2015). The geometry of distributional preferences and a non-parametric identification approach: The Equality Equivalence Test. European Economic Review, 76, 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.01.008

Kim, J., Kim, Y., & Zhou, J. (2017). Languages and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 63(2), 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2017.04.001

Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2009). Field experiments in economics: The past, the present, and the future. European Economic Review, 53(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2008.12.001

Liang, H., Marquis, C., Renneboog, L., & Sun, S. L. (2018). Future-time framing: The effect of language on corporate future orientation. Organization Science, 29(6), 1093–1111. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2018.1217

Maniadis, Z., & Tufano, F. (2017). The research reproducibility crisis and economics of science. Economic Journal, 127, F200–F208. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12526

Maniadis, Z., Tufano, F., & List, J. A. (2014). One swallow doesn’t make a summer: New evidence on anchoring effects. American Economic Review, 104(1), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.1.277

Mavisakalyan, A., Tarverdi, Y., & Weber, C. (2018). Talking in the present, caring for the future: Language and environment. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(4), 1370–1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2018.01.003

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2658056

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108

Pérez, E. O., & Tavits, M. (2017). Language shapes people’s time perspective and support for future-oriented policies. American Journal of Political Science, 61(3), 715–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12290

SIL International (2020). What are the top 200 most spoken languages? https://www.ethnologue.com/guides/ethnologue200. Accessed Nov 4, 2020.

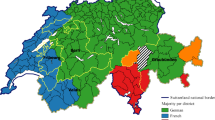

Sutter, M., Angerer, S., Glätzle-Rützler, D., & Lergetporer, P. (2018). Language group differences in time preferences: Evidence from primary school children in a bilingual city. European Economic Review, 106, 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.04.003

Sutter, M., Kocher, M. G., Glätzle-Rüetzler, D., & Trautmann, S. T. (2013). Impatience and uncertainty: Experimental decisions predict adolescents’ field behavior. American Economic Review, 103(1), 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.1.510

Thieroff, R. (2000). On the areal distribution of tense-aspect categories in Europe. In Ö. Dahl (Ed.), Tense and aspect in the languages of Europe (pp. 309–328). Mouton de Gruyter.

Whorf, B. L. (1956). Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Winawer, J., Witthoft, N., Frank, M. C., Wu, L., Wade, A. R., Boroditsky, L. (2007). Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(19), 7780-7785. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Acknowledgements

We thank Dirk Engelmann, Maria Bigoni and two referees for very helpful comments. We are also grateful to Ayse Yilmaz, Esra Gkcee and Fati Öztürk for excellent research assistance. Financial support from the Government of the autonomous province South Tyrol through Grant 315/40.3 is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

This study was funded by Government of the autonomous province South Tyrol Grant 315/40.3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Angerer, S., Glätzle-Rützler, D., Lergetporer, P. et al. The effects of language on patience: an experimental replication study of the linguistic-savings hypothesis in Austria. J Econ Sci Assoc 7, 88–97 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-021-00103-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-021-00103-x