Abstract

Students’ perceptions of teaching quality and teachers’ interaction with their families, along with student self-efficacy and interest in a subject matter to performance. However, little is known about how student perceptions of teaching quality and teacher-family interactions in the subject of English relate to performance in reading comprehension. The current study explores how the teacher-related perceptions of New Zealand senior secondary students relate to their reading attitudes and tested reading comprehension. Partially mediated structural equation modelling revealed that students’ perceptions of teaching quality directly and positively influenced student self-efficacy, interest, and performance and indirectly through self-efficacy. However, perceptions of teacher-family interactions negatively influenced student self-efficacy and performance and were not related to interest. Although the model was statistically invariant across demographic variables, there were large latent mean differences across school decile bands for reading performance. These findings reinforce the importance of student perceptions of good teaching and raise challenges about how teachers interact with families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Not only does good teaching matter to student learning (Basow, 2000; Beishuizen et al., 2001; Labak et al., 2017; van der Lans & Maulana, 2018) but also students have to perceive that the teaching they experience is high-quality (Irving, 2004; Stronge, 2006). However, few studies have examined student perceptions of teaching quality and teacher-family interaction as predictors of performance (Akram, 2019; Wilkerson et al., 2000). Extensive research has shown that student self-efficacy beliefs (Zimmerman, 2000) and student interest in a subject (Hattie, 2008; Marsh et al., 2006) contribute to academic achievement in reading comprehension. While we might expect that students who perceive their teachers as giving high-quality teaching and interact positively with their families would also report better performance, greater interest, and self-efficacy in the subject. Nonetheless, it remains uncertain whether this is a valid assumption. This article contributes to that gap by describing a cross-sectional student self-report survey of senior high school students about their perceptions of English teaching quality, the quality of their teacher-family interactions, their self-efficacy, their interest in reading, and their performance on a reading comprehension test. This study adds to our understanding of student perceptions of teaching quality from the very people expected to benefit from it.

Student Perceptions of Teaching Quality

Student perceptions of teaching quality are an interesting way to evaluate teaching quality. In Stronge’s (2006, p. 135) words, students are ‘the primary consumers of the teachers’ services’ and the ‘direct recipients of the teaching-learning process’. Further, only students have direct classroom experience with teachers on a regular, long-term basis. Therefore, compared to other stakeholders (e.g., peers or headteachers), students can provide the most meaningful judgements of teaching quality. Research has found that students can be a valid source of information concerning how well a teacher teaches. For example in the USA, Kane and Staiger (2012) reported that high school student perceptions of teaching using the Tripod Student Perception Survey focused on “seven constructs: Care, Control, Clarify, Challenge, Captivate, Confer, and Consolidate” (p. 17) produced stable and reliable data compared to classroom observational data. In higher education, there is reasonably strong evidence that students are generally good judges of teaching quality (McKeachie, 1990). The two most well-known of student perceptions of teaching quality inventories are the Students’ Evaluations of Educational Quality (SEEQ), and Course Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) (Richardson, 2005). Across the two instruments common characteristics of teaching practice are foregrounded (i.e., CEQ: good teaching, clear goals and standards, appropriate workload and assessment, emphasis on independence; SEEQ: learning/value, enthusiasm, organization, group interaction, individual rapport, breadth of coverage, examinations/grading, assignments and workload/difficulty). In the compulsory school sector, Irving (2004) showed that American high school students were able to effectively identify from items related to cognitive challenge, challenging material, working together in class, valuing mathematics, and mathematical thinking and reasoning whether their teacher had passed the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards examination. Thus, structured student surveys can be aligned to valued aspects of teaching practice.

Further, there is evidence that teachers whose students give them higher scores on inventories of teaching quality tend to have students with greater academic achievement (Akram, 2019; Sanders & Rivers, 1996; Wilkerson et al., (2000). Thus, it is entirely possible that New Zealand secondary school students could identify the degree to which they experienced high-quality teaching practices when prompted with a student self-report survey and that those responses would be positively associated with performance.

Parental Involvement Effect on Student Performance, Self-efficacy, and Interest

Teacher-family interaction, more often called school-family connection or parental involvement in the literature, refers to the interaction of teachers with the important adults in students’ domestic situation. Theoretically, teacher communication with parents should be a positive experience, if teachers reach out to praise or otherwise compliment student behaviour, academic performance, or social skills. However, in many cases, the communication is more often negative with complaints or concerns about the student’s well-being, behaviour, or academic performance. (Fan, 2001) reported that more frequent teacher-family interaction was related to lower school performance. Thus, the effects of parental involvement on student performance in secondary education are inconsistent (Alton-Lee et al., 2009; Hill & Tyson, 2009). Even for the same type of parental involvement, inconsistent results appear, depending on whether involvement was measured by students’ perceptions (Deslandes & Cloutier, 2002), teachers’ perceptions (Gordon & Louis, 2009), or parents’ perceptions (Affuso et al., 2017; Fan & Williams, 2010). Thomas et al. (2020) found that parents reported a higher level of parental involvement than students.

Research on parental involvement as a predictor of students’ academic motivation is limited. Broadly speaking, parental involvement is believed to be positively associated with students’ motivation (Gonzalez-DeHass et al., 2005). Parental involvement can indirectly influence academic achievement via parents’ satisfaction with school (Hampden-Thompson & Galindo, 2017) or student self-efficacy and self-determined motivation (Affuso et al., 2017). W. Fan and Williams (2010) found that student self-efficacy and interest in English were strongly and positively associated with teacher-initiated communication with parents about benign school issues but negatively associated with teacher-parent communication about student school problems and that parent-initiated communication regarding benign school issues was not significantly related to student self-efficacy.

However, most research has drawn attention to populations below eighth grade (W. Fan & Williams, 2010). There is a need to examine the relation between parental involvement and student self-efficacy, interest, and performance in the senior secondary school student population, a matter addressed here.

Student Self-Efficacy in Reading

Self-efficacy is one’s belief in his or her ability to manage specific tasks (Bandura, 1977), such as the ability to read a specific novel, rather than more general judgements of being a good reader, which is better understood as self-concept (Hattie, 1992). Many studies have reported that there is a significant positive relation between self-efficacy beliefs and academic performance, including reading achievement (Guthrie et al., 2013; Moulton et al., 1991). In Solheim’s (2011) study, only reading self-efficacy, not reading task value, was statistically significant in predicting performance. Understandably, a strong source of positive self-efficacy is the ability to do well (Chin & Kameoka, 2002; Talsma et al., 2018), so we might expect weaker students to have lower self-efficacy. However, based on a large survey of New Zealand students, ‘Otunuku & Brown (2007) found that self-efficacy had statistically significant positive relations to reading achievement for Asian and Pākehā students, while Māori and Pasifika students’ self-efficacy had correlations to performance not different to zero. Given that the latter two groups had substantially lower reading scores than the former groups, it was suggested that lack of challenging instruction and materials contributed to the zero correlations between self-efficacy and performance for the latter groups.

Student Interest in Reading

Interest is a central feature of intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Wigfield & Cambria, 2010; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Interested students have curiosity about a subject, are attentive to it, and concentrate upon it. Teachers are often exhorted to activate student interest in their subject to support learning. This is situational interest, which involves creating an environment that makes a task or problem exciting and motivating, and is important in early periods of expertise development (Alexander, 2005). In contrast, individual interest is a long-term, more stable disposition toward a specific domain, which ought to exist among senior secondary school students because of their greater competence in the subject. Unfortunately, generally, as students age through the school system, their interest in reading declines (Wigfield et al., 1997). Thus, the importance of reading interest to reading performance is inconsistent. Taboada et al. (2008) found that interest in reading predicted students’ reading achievement progress when students’ previous reading achievement was controlled. Across 41 countries, Chiu and Chow (2010) found that students with higher reading interests had higher reading scores than other students. However, Retelsdorf et al. (2011) reported that interest in reading was not statistically significantly linked to initial reading achievement but was a statistically significant predictor of achievement growth. Nevertheless, an important goal of schooling is that students enjoy and take an interest in the skills and subjects they are being taught (Silvia, 2008).

Context: Reading Comprehension in NZ English Teaching

In NZ, reading and writing are taught together in a course called English. When the data in this study were collected, English teaching and learning in NZ was under the guidance of a national curriculum statement that divided English into three strands—Oral (listening and speaking), Written (reading and writing), and Visual Language (viewing and presenting) (Brown, 1998; Ministry of Education, 1994). The focus and purpose of the English curriculum have been summarised as:

English is not to be primarily a content subject; it is to be about the processes used by an individual to construct a response to a text or to initiate a text. Responses and texts express ideas, emotions, thoughts, personal experiences, aesthetic, moral or philosophic values, and so on. The processes of expression are taught rather than the content of the individual student’s expression. The meaning and power of a text lies in its language. (Brown, 1998, p. 66)

The reading strand consisted of two functions (i.e., personal reading and close reading), with close reading evaluated in end-of-year external examinations as part of the school qualifications system (Crooks, 2002). Close reading involves ‘reading to develop detailed understanding, involving the identification of distinctive language features such as vocabulary, imagery, and structure, and how these contribute to meanings, implications, and effects’ (Ministry of Education, 1994, p. 139). Students are expected to study texts for further and deeper meanings rather than just extract surface level information. In contrast, personal reading speaks to the importance of reading widely for personal pleasure and interest and was generally assessed through coursework and classroom activities.

Although NZ updated the curriculum in 2007 (Ministry of Education, 2007), our reading of the two documents suggests that the revision did not change the substantive core skills, knowledge, or abilities of reading comprehension. Instead, the revision made structural changes to the overarching classification and organisation of the curricular content. This indicates that data linked to the 1994 curriculum at the level of achievement objectives has currency for the current 2007 curriculum. In other words, regardless of the labels, the substance of reading comprehension is not different despite terminological changes. Technological developments since these data were collected might have changed some methods of teacher reporting to parent to include online or electronic reporting, teacher-parent interviews and conversations are still important features of teacher-parent interactions. A continuing important feature of teacher-parent interactions is communication about student achievement (Hill, 2019).

Research Goal

This study aimed to understand how senior secondary students evaluated the teaching quality and teacher-family interaction they perceived and relate them to their interest in, self-efficacy for, and performance in reading comprehension. We hypothesised that students with positive evaluations of teaching quality and teacher-family interaction would have greater interest, self-efficacy, and performance. One question is explicitly addressed:

How do student perceptions of teaching quality and teacher-family interaction affect students’ reading self-efficacy, interest, and performance in secondary school?

Method

The Data

The study uses normative data collected for the Assessment Tools for Teaching and Learning Version 4 (asTTle V4) test system (Hattie et al., 2004). asTTle is a computer-assisted assessment system for use in mathematics, reading, and writing curricular areas with norms for students in Years 4 to 12 against the objectives of Curriculum Levels 2 to 6 both in English and Māori. The asTTle system is provided free to all NZ primary and secondary schools. The asTTle V4 database contains performance and attitudinal data (i.e., self-efficacy and interest) of approximately 30,000 Year 4–12 students in reading comprehension or close reading (Hattie, 2008). As part of the norming process, research questions about various aspects of teaching and learning were included in the test forms, which students completed after they had taken a 40-minute asTTle test. All test forms included questions about self-efficacy and interest in the subject being tested. The survey items about teaching quality were included only in some of the Year 11 and 12 tests of reading comprehension, which were randomly assigned to schools. Note that Level 6 of the curriculum is aligned to the expected performance of students in Year 11 and is aligned to the first level of the New Zealand school qualifications system (Crooks, 2011).

The asTTle project data were collected with permission from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (HPEC Reference 2000/296). All participants gave consent by completing the anonymous 40-minute close reading comprehension test and attached research questions and submitting them to the asTTle team. This meant that reading performance could be connected to student evaluation of teaching, their self-efficacy, and interest in the tested subject. Access to an anonymised version of the data for secondary analysis was given by the second author, who had been a senior manager on the asTTle project.

Participants

The reading comprehension testing of Levels 4 to 6 were administered in 63 secondary schools (19% of 340 schools) and involved 13,606 students from Year 9 to 12 (Hattie et al., 2004). Of the 4,680 students tested in Years 11 and 12 (nominally aged 16–17) for reading comprehension, 684 (15%) students were assigned to tests with the survey of teaching quality items. Since there is no reliable method to impute missing demographic information, those participants were removed from the sample (n = 2). According to Bennett (2001), statistical analysis is likely to be biased if the percentage of missing data is more than 10%. Therefore the student survey items were deleted from the sample (n = 47, 7%), resulting in 635 valid cases (93% response rate) (Table 1). Given that the target was Curriculum Level 6, the proportion of Year 11 students was higher than Year 12 students, by approximately three to two. The participants were almost equally divided by gender, with a slight advantage to boys.

All students self-reported their ethnicities. Standard New Zealand Statistics rules were utilised to assign students to a single group if multiple groups were chosen (‘Otunuku & Brown, 2007). Students who reported Māori and any other ethnicity were classified as Māori. Students who indicated Pacific Islander and any other ethnicity were classified as Pacific Islander. Students who chose Asian and any other ethnicity were grouped into Asian. Students who only chose Pākehā / NZ European were assigned to that group. While there are other classification systems (Yao et al., 2022), the raw data of possible multiple ethnicity identification is not available in the anonymised data set. Nevertheless, the sample corresponded to the proportion of ethnicities in the population for the 2006 Census data and the latest 2023 Census data (Stats NZ, 2020, 2024). Although the data are 20 years old, the demographic consistency over time suggests that the findings remain relevant.

The socio-economic status of participants is inferred from the school decile rating, which represents the proportion of the population in the lowest (1) to highest (10) social-economic communities (Ministry of Education, n.d.). Schools were classified as low decile if they were in deciles 1–3, medium in deciles 4–7, and high in deciles 8–10. Students were from 31 schools. Schools were almost equally divided across the deciles (Low = 10; Medium = 13; High = 8). The proportion of participants from medium and high decile schools was similar and nearly twice as large as those from low decile schools. It is worth noting that school decile rating is an aggregate measure and may not reflect the socio-economic status of individual students. However, despite this limitation, school decile rating provides useful insights into the broader socio-economic context in which the student is situated.

Instruments

This study uses three instruments to measure student perceptions of teaching, their attitudes toward reading, and their performance in close reading.

Perceptions of English Teaching

This inventory was adapted from Irving’s (2004) instrument for student evaluation of highly accomplished teaching of mathematics classes. Irving’s study found that student survey items could classify with 65% accuracy whether the evaluated teachers had won the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards Highly Accomplished Teacher status. Ten items that most strongly predicted high-quality teaching in mathematics were adapted to teaching English (Appendix A). A small set of items was adopted to reduce potential fatigue at the end of a 40-minute test. Eight items related to teaching quality (e.g., my teacher challenges me to think through and resolve issues) and two items for teacher-family interaction (e.g., my teacher seeks information from my family about my strengths, interest, habits, and home life).

All items had positively framed verbs, so degree of agreement could be evaluated using a 6-point, positively packed (Lam & Klockars, 1982) rating scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = mostly disagree, 3 = slightly agree, 4 = moderately agree, 5 = mostly agree, 6 = strongly agree). Positive packing works well when there is likely to be strong social desirability toward a phenomenon, which might be the case for students rating their own teacher. Packing the response options in the expected positive direction gives more options in the positive space, resulting in superior statistical characteristics to equally spaced or balanced response scales, resulting in more variation in responses (Klockars & Yamagishi, 1988).

Attitudes Toward the Reading Subject

The questionnaire on attitudes to the reading subject contained six items retrieved from the National Education Monitoring Project (NEMP) (Hattie et al., 2004). Two inter-correlated scales each had three items: self-efficacy and interest in reading subject. Students indicated their responses by choosing one of four faces (1 = very sad face, 2 = sad face, 3 = happy face, 4 = very happy face).

Reading Performance

Students’ reading performance were derived from a single-parameter item response theory (IRT) scoring system such that students who answered more difficult questions correctly got higher scores (Hattie et al., 2004). The IRT scoring method means students can be compared across schools, year groups, and time. Items were classified as either surface or deep according to the Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes (SOLO) cognitive processing taxonomy (Hattie & Brown, 2004). While the system provides a single value score, we used the two SOLO sub-scores to model total reading as a latent construct predicting these two comprehension features.

Data Analysis Procedure

Because the ten teaching quality items were designed to be in two scales, a two correlated factor model was tested with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Jamovi Version 1.6.3 (The jamovi project, 2020) to evaluate the fit between the observed data and the hypothesised measurement models. Maximum likelihood estimation was used because six-point ordinal rating scales behave as if they are continuous variables (Finney & DiStefano, 2006). The small amounts of missing data were estimated with the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) protocol.

Although the data are cross-sectional, we examined the possibility that causal paths among constructs might better fit the data than a simple inter-correlated model. Because multiple models can fit data (Revelle & Rocklin, 2010), we evaluated seven different models as to how the five constructs (i.e., student self-efficacy, student interest, student perceptions of teaching quality and teacher-family interactions, and test performance) were related to each other. The seven alternative path models were:

-

M0: There is no causality; all factors inter-correlated.

-

M1: Student perceptions of teaching quality and teacher-family interaction are predictors of self-efficacy, interest in, and performance in the subject, with self-efficacy and interest positioned as mediators between student perceptions of teaching and performance.

-

M2: Test performance predicts all psychological constructs.

-

M3: Perceptions of teaching quality are the source of all other constructs.

-

M4: Perceptions of teacher-family interaction are the source of all other constructs.

-

M5: Self-efficacy is the source of all other constructs.

-

M6: Interest is the source of all other constructs.

These seven SEM models were evaluated with the lavaan package version 0.6-7 (Rosseel, 2012) in R version 4.0.3 (R Core Team, 2020). The difference in Akaike information criterion (AIC) (∆i) between the lowest scoring model and all other comparison models was used, with values ∆i > 10 suggesting substantial evidence for the lowest value model as the best model (Burnham & Anderson, 2004). All models with AIC index weight (wi > 0.95) can be considered equivalent.

Once the best model was determined, nested multigroup invariance was used to test if different demographic groups were equivalent groups (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Changes in comparative fit indices (∆CFI) and changes in root mean square error of approximation (∆RMSEA) were selected as the primary criterion, with ∆CFI < 0.01 and ∆RMSEA < 0.015 indicating invariance achieved across groups (Chen, 2007). Since the number of students in the different ethnic groups varied considerably (i.e., Pākehā / NZ European n > 300, whereas all other ethnic groups had n < 100; Table 1), all the minority ethnic groups were aggregated into one group for comparison against the Pākehā / NZ European group.

Assuming a model was invariant for regression loadings (metric) and regression intercepts (scalar) across different groups, then, latent means could be compared across different groups. Otherwise, separate models for each group would have to be reported. In testing for latent mean differences, one group functions as the reference group against which other groups are compared. In the reference group, factor means are converted to a z-score (M = 0, SD = 1) (Byrne, 2001), so the estimated mean for comparison groups is a standard deviation difference relative to zero. Cohen’s d (1992) was used as the effect size index, with values < 0.20 treated as trivial, between 0.20 and 0.50 as small, between 0.50 and 0.80 medium, and > 0.80 as large.

Results

The baseline inter-correlated model (M0) had statistically significant inter-correlations (Table 2), except for teacher-family interaction to interest. Most correlations were small (0.10 < r <.30), and a few were modest (0.30 < r <.55). The relations of teacher-family interaction to self-efficacy and performance were negative, meaning greater teacher-family interaction was associated with less student self-efficacy and performance.

All models (Supplementary Table S1), except M2 (inadmissible), had acceptable (M5, M3, M6, and M4) to good (M1 and M0) fit. Although Model M0 had good fit indices, Model M1 had considerably lower AIC values indicating it had the best correspondence to the data (wi = 1.00), supporting the causal hypothesis that students’ overall perceptions of teaching quality and family interaction with their English teacher influence their self-efficacy, interest, and performance on a test of reading comprehension. Supplementary Table S2 provides standardised beta factor loadings and items of Model M1. Given the strong loading of items on their latent scales, measures of scale reliability (Coefficient H, McDonald’s ω) were strong.

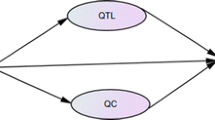

Within causal path Model M1 (Fig. 1), perceptions of teaching quality and teacher-family interactions were positively correlated. However, they had different relations to subsequent constructs. Perceptions of teaching quality positively regressed onto interest, self-efficacy, and performance. This supports the claim that the more students perceived that their teachers had done these quality activities, the more interest and self-efficacy they reported, and the greater their academic achievement. In contrast, perceptions of teacher-family interaction had negative relations to self-efficacy, interest (albeit not statistically different to zero), and performance. This suggests that increased endorsement that teachers interacted with home, the more negative effect it had on performance and attitudes to the subject. Perhaps those interactions were predominantly about teacher concerns, rather than compliments.

Schematic mediated path diagram of student perceptions of teaching English, interest, self-efficacy, and performance in reading (M1). Note. All values are standardised. Solid lines denote statistically significant paths, while dotted lines denote non-statistically significant paths. All residual errors removed for simplicity. ET = English teaching; r_att = Reading attitude; readdeep = SOLO Deep Processes in Reading; readsurf = SOLO Deep Processes in Reading

Self-efficacy and interest had different relations to academic performance, despite having a positive inter-correlation. Specifically, interest in reading had a zero relationship with reading performance, while greater self-efficacy had positive relations with performance. As expected, given the greater difficulty of deep items, the overall test performance loaded more strongly on the deep features than surface ones. In total, this model combining student perceptions of teaching quality and teacher-family interaction and subject attitudes accounted for 24% of the variance in the performance score, a substantial result.

The results of nested multigroup invariance testing (Supplementary Table S3) demonstrated that M1 was strongly invariant for all demographic group comparisons. In comparing the latent mean across groups (Supplementary Table S4), there were only trivial differences (d < 0.20) between different year groups, except for interest which had a small advantage to Year 12, indicative of greater individual interest among students who would have already completed the first level of qualifications. Similarly, differences were trivial (d < 0.20) between males and females except for interest which had a small effect in favour of young women, again consistent with the research literature (Schwabe et al., 2015).

In terms of ethnic groups, the minority group had a small increase in teacher-family interactions and interest in reading, but had a small drop in self-efficacy and a medium drop in reading performance. School decile differences between medium and high decile were all small (0.20 < d < 0.50). However, there was a large difference in academic performance in reading against the low decile schools, and a small increase in teacher-family interaction compared to high decile schools.

Across these comparisons, there were no meaningful differences for teaching quality, trivial to small differences for teacher-family interaction by year, ethnicity and school decile, small differences for interest by year, sex, and ethnicity, small differences for self-efficacy by ethnicity, and consistently large differences against low decile schools in performance by school decile.

Discussion

As expected (Akram, 2019; Wilkerson et al., 2000), student beliefs about the teaching quality they experienced positively contributed to self-efficacy, interest, and performance on a reading comprehension test. This shows that it matters that students perceive their teacher challenging and interacting with them within the subject being taught. This perception engenders greater interest in and self-efficacy for reading comprehension, all desirable outcomes for all stakeholders. Nevertheless, we cannot tell that teachers rated highly by their students were actually better teachers, only that the students perceived it with positive consequences.

Like some previous studies (W. Fan & Williams, 2010), teacher interactions with families had a negative relationship to performance and self-efficacy. Given that this negative effect was most visible in the contrast between low and high decile schools which also had a large difference in academic performance, perhaps the teacher-parent interactions in those schools were more likely focused on academic or motivational problems. Such interactions may result in subsequent punitive and discouraging conversations between parents and students. Hence, it would be relatively easy for students in struggling academic contexts to resent frequent parent-teacher interactions that draw attention to academic performance or motivational attitudes. However, it is clear that the measurement of parent-teacher interaction is limited by consisting of only two items, giving a very narrow perspective on that construct. Future research needs to expand the pool of items to include the positive and negative ways teachers can interact with families. Triangulating the data from students with that from parents may also help as there is likely to be a reciprocal reinforcing relationship between students and their parents/guardians (Brown & Eklöf, 2018). Research with students across the childhood lifespan would also establish whether teacher-family interaction becomes more negative as students age through the school system.

While being interested in a phenomenon leads to greater motivation and effort (Hattie, 2008; Marsh et al., 2006; Taboada et al., 2008), in this case, interest in reading was irrelevant to reading performance. This result is consistent with previous studies that found that the effects of subject interest declined through school years (Rothman & McMillan, 2003; Wigfield et al., 1997) and had little relationship to performance (Retelsdorf et al., 2011). The fundamentally zero path from teacher-family interaction to interest may suggest that parents expect teenagers to choose their own interests, resulting in diversity of interests catered for by secondary school curriculum.

Consistent with previous research (Shell et al., 1989; Solheim, 2011), self-efficacy was the most potent predictor of reading performance of all constructs measured. The positive effect of self-efficacy upon performance means that higher levels of self-efficacy constitute a justified self-belief; that is, students have stronger self-efficacy perceptions and who actually perform better are justified in their self-perception (Michaelides et al., 2019). Most importantly, the study highlights a route by which student self-efficacy in reading could be enhanced—high quality classroom teaching practices. To improve student self-efficacy and performance, teachers can challenge students to think through and resolve issues, cater for the issues students commonly encounter, make English satisfying and stimulating, put high value on the subject, and help students develop critical thinking.

Interestingly, the pairs of positively correlated constructs (i.e., interest with self-efficacy and teaching quality with teacher-family interaction) had non-transitive effects on performance. When correlations between constructs are relatively far from 1.00, as is the case here, it is possible for positively correlated constructs to have inverse effects on a third variable (Kim & Mueller, 1978). SEM is ideally situated to disentangle this situation (Kim & Mueller, 1978); hence we can be confident in the strength and valence of path results in this study.

Implication

Based on this study of senior secondary school English students in NZ, it seems teachers would do well to ensure students experience the qualities described in the teaching quality scale and focus more on students developing the competencies they need for successful reading. The study suggests students need not become as interested in the subject as teachers might hope. Instead, the study suggests that an emphasis on helping students to competence in the subject is more valuable than interest. By this students gain a justified self-efficacy rather than an inflated sense of self-concept.

In terms of teacher-family interaction, albeit challenging to implement, teachers need to develop patterns of communication with families long before problems arise so that such communication is not presumed to be ‘bad news’. Perhaps greater use of technology to deliver constructive, formative feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007) to students and families, rather than waiting until things have gone wrong, would engender a culture of positive teacher-family interaction.

A concern many readers might have is the dated nature of the data. Our argument is that despite formal changes in the curriculum statements, the survey items capture relatively universal and perpetual instructional goals of and strategies for senior secondary school English teaching. Although technology has developed in the past 20 years, what and how English lessons are taught and what teachers communicate with families have not changed fundamentally. Therefore, we suggest that English teaching would benefit from consideration of these results.

A clear challenge to the interpretation given here of the statistical model is that it depends on cross-sectional data. Causal interpretations, as we have offered here, require experimental proof in which the quality of teaching can be manipulated. The characteristics of teaching quality identified in Appendix A seem to be laudable and defensibly appropriate good ways to teach English. Perhaps a serious consideration of the teaching methods identified in the science of instruction would further help students improve competencies (Kirschner et al., 2006; Rosenshine, 2012).

It is important to bear in mind that the results here reflect students’ perceptions of their teacher’s quality; they are not an objective or independent evaluation of teacher quality. While the student evaluation of teaching research is robust, in this case, We do not know if students see teacher practices in the same way as experts in teaching would. Future research could include an expert observational component that determines the degree to which student perceptions are valid. Nonetheless, the current results align well with other research.

Conclusion

This study adapted Irving’s (2004) research in mathematics to the field of English language arts. The results point to important insights into how teachers can contribute to student learning outcomes. Students who perceive they have been given high-quality teaching have greater self-efficacy and performance. The causal model strongly suggests that this is the correct direction of influence. As such, this suggests productive ways for teachers to develop their instructional practices and goals.

Appendix A. Student Perceptions of Teaching Quality Items

Quality of Teaching

ET1: Gets me to think about the nature and quality of my work.

ET2: Helps me to understand that English relates to the real world.

ET3: Makes learning English satisfying and stimulating.

ET4: Challenges me to think through and resolve issues.

ET5: Knows and caters for the issues that we commonly encounter in learning new literature, language, or ideas.

ET6: Encourages me to place a high value on English literature and language.

ET8: Develops my ability to think and reason critically.

ET10: Teaches me the basic processes of English – for example, understanding texts, making inferences, communicating effectively, and appreciating the art of writing.

Teacher-Parent Interactions

ET7: Seeks information from my family about my strengths, interests, habits, and home life.

ET9: Keeps my family informed on regular basis about my progress in English.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.17608/k6.auckland.19310834.

References

Affuso, G., Bacchini, D., & Miranda, M. C. (2017). The contribution of school-related parental monitoring, self-determination, and self-efficacy to academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 110(5), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2016.1149795

Akram, M. (2019). Relationship between students’ perceptions of teacher effectiveness and student achievement at secondary school level. Bulletin of Education and Research, 41(2), 93–108.

Alexander, P. A. (2005). The path to competence: A lifespan developmental perspective on reading. Journal of Literacy Research, 37(4), 413–436. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3704_1

Alton-Lee, A., Robinson, V., Hohepa, M., & Lloyd, C. (2009). Creating educationally powerful connections with family, whānau, and communities. In V. Robinson, M. K. Hohepa, C. Lloyd, & New Zealand Ministry of Education, School leadership and student outcomes: Identifying what works and why: Best evidence synthesis iteration (BES) (pp. 142–170). Ministry of Education.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Basow, S. A. (2000). Best and worst professors: Gender patterns in students’ choices. Sex Roles, 43, 407–417.

Beishuizen, J., Hof, E., van Putten, C., Bouwmeester, S., & Asscher, J. (2001). Students’ and teachers’ cognitions about good teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(2), 185. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158451

Bennett, D. A. (2001). How can I deal with missing data in my study? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25(5), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x

Brown, G. T. L. (1998). The New Zealand english curriculum. English in Aotearoa, 35, 64–70

Brown, G. T. L., & Eklöf, H. (2018). Swedish student perceptions of achievement practices: The role of intelligence. Intelligence, 69, 94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2018.05.006

Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R. (2004). Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods & Research, 33(2), 261–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Chin, D., & Kameoka, V. A. (2002). Psychosocial and contextual predictors of educational and occupational self-efficacy among hispanic inner-city adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 24(4), 448–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986302238214

Chiu, M. M., & Chow, B. W. Y. (2010). Culture, motivation, and reading achievement: High school students in 41 countries. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(6), 579–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.03.007

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Crooks, T. J. (2002). Educational assessment in New Zealand schools. Assessment in Education: Principles Policy & Practice, 9(2), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594022000001959

Crooks, T. (2011). Assessment for learning in the accountability era: New Zealand. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.002

Deslandes, R., & Cloutier, R. (2002). Adolescents’ perception of parental involvement in schooling. School Psychology International, 23(2), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034302023002919

Fan, X. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A growth modeling analysis. The Journal of Experimental Education, 70(1), 27–61.

Fan, W., & Williams, C. M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903353302

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock, & R. D. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 269–314). Information Age Publishing.

Gonzalez-DeHass, A. R., Willems, P. P., & Doan Holbein, M. F. (2005). Examining the relationship between parental involvement and student motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-3949-7

Gordon, M. F., & Louis, K. S. (2009). Linking parent and community involvement with student achievement: Comparing principal and teacher perceptions of stakeholder influence. American Journal of Education, 116(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/605098

Guthrie, J. T., Klauda, S. L., & Ho, A. N. (2013). Modeling the relationships among reading instruction, motivation, engagement, and achievement for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(1), 9–26.

Hampden-Thompson, G., & Galindo, C. (2017). School–family relationships, school satisfaction and the academic achievement of young people. Educational Review, 69(2), 248–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1207613

Hattie, J. (1992). Self-concept. L. Earlbaum Associates.

Hattie, J. (2008). Some correlates of academic performance in New Zealand schools: The asTTle database. In C. M. Rubie-Davies, & C. Rawlinson (Eds.), Challenging thinking about teaching and learning (pp. 75–96). Nova Science.

Hattie, J., & Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Cognitive processes in asTTle: The SOLO taxonomy [asTTle Technical Report 43]. https://e-asttle.tki.org.nz/content/download/1499/6030/version/1/file/43.+The+SOLO+taxonomy+2004.pdf

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hattie, J., Brown, G. T. L., Keegan, P. J., MacKay, A. J., Irving, S. E., Cutforth, S., Campbell, A. R. T., Patel, P., Sussex, K., Sutherland, T., McCall, S., Mooyman, D., & Yu, J. (2004). Assessment Tools for Teaching and Learning (asTTle) manual (version 4, 2005). University of Auckland/ Ministry of Education/ Learning Media. https://doi.org/10.17608/k6.auckland.14977503.v1

Hill, M. F. (2019). Using classroom assessment for effective learning and teaching. In M. Hill & M. Thrupp (Eds.), The professional practice of teaching in New Zealand (6th edition, pp. 110–132). Cengage Learning.

Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology, 45(3), 740–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015362

Irving, S. E. (2004). The development and validation of a student evaluation instrument to identify highly accomplished mathematics teachers [Thesis, The University of Auckland]. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/326

Kane, T. J., & Staiger, D. O. (2012). Gathering feedback for teaching: Combining high-quality observations with student surveys and achievement gains [Research Paper. MET Project]. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED540960

Kim, J., & Mueller, C. (1978). Factor analysis: Statistical methods and practical issues (Vol. 14). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984256

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Klockars, A. J., & Yamagishi, M. (1988). The influence of labels and positions in rating scales. Journal of Educational Measurement, 25(2), 85–96.

Labak, I., Čikeš, A. B., & Pale, P. (2017). Students perception: How does a favorite teacher behave. Schülerwahrnehmung: Wie Verhält Sich Der Lieblingslehrer, 63(2), 35–48.

Lam, T. C. M., & Klockars, A. J. (1982). Anchor point effects on the equivalence of questionnaire items. Journal of Educational Measurement, 19(4), 317–322.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., Artelt, C., Baumert, J., & Peschar, J. L. (2006). OECD’s brief self-report measure of educational psychology’s most useful affective constructs: Cross-cultural, psychometric comparisons across 25 countries. International Journal of Testing, 6(4), 311–360. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327574ijt0604_1

McKeachie, W. J. (1990). Research on college teaching: The historical background. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(2), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.2.189

Michaelides, M., Brown, G. T. L., Eklöf, H., & Papanastasiou, E. (2019). Motivational profiles in TIMSS mathematics: Exploring student clusters across countries and time (Vol. 7). Springer Open & IEA. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030261825

Ministry of Education (n.d.). School deciles. Ministry of Education. https://www.education.govt.nz/school/funding-and-financials/resourcing/operational-funding/school-decile-ratings/

Ministry of Education. (1994). English in the New Zealand curriculum. Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Learning Media.

Moulton, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 38, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.38.1.30

‘Otunuku, M., & Brown, G. T. L. (2007). Tongan students’ attitudes towards their subjects in New Zealand relative to their academic achievement. Asia Pacific Education Review, 8(1), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03025838

R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (4.0.3) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Retelsdorf, J., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2011). On the effects of motivation on reading performance growth in secondary school. Learning and Instruction, 21(4), 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.11.001

Revelle, W., & Rocklin, T. (2010). Very simple structure: An alternative procedure for estimating the optimal number of interpretable factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr1404_2

Richardson, J. T. E. (2005). Instruments for obtaining student feedback: A review of the literature. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 387–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500099193

Rosenshine, B. (2012). Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator, 36(1), 12–21.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rothman, S., & McMillan, J. (2003). Influences on achievement in literacy and numeracy. (Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY) Research Report 36). Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). https://research.acer.edu.au/lsay_research/40

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sanders, W. L., & Rivers, J. C. (1996). Cumulative and residual effects of teachers on future academic achievement [Research progress report]. University of Tennessee Value-Added Research and Assessment Center.

Schwabe, F., McElvany, N., & Trendtel, M. (2015). The school age gender gap in reading achievement: Examining the influences of item format and intrinsic reading motivation. Reading Research Quarterly, 50(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.92

Shell, D. F., Murphy, C. C., & Bruning, R. H. (1989). Self-efficacy and outcome expectancy mechanisms in reading and writing achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(1), 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.81.1.91

Silvia, P. J. (2008). Interest—the curious emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(1), 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00548.x

Solheim, O. J. (2011). The impact of reading self-efficacy and task value on reading comprehension scores in different item formats. Reading Psychology, 32(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710903256601

Stats, N. Z. (2024, May 29). 2023 Census population counts (by ethnic group, age, and Māori descent) and dwelling counts. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/2023-census-population-counts-by-ethnic-group-age-and-maori-descent-and-dwelling-counts/

Stats, N. Z. (2020, September 3). Ethnic group summaries reveal New Zealand’s multicultural make-up. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/ethnic-group-summaries-reveal-new-zealands-multicultural-make-up

Stronge, J. H. (2006). Evaluating teaching: A guide to current thinking and best practice (2nd ed.). Corwin.

Taboada, A., Tonks, S. M., Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (2008). Effects of motivational and cognitive variables on reading comprehension. Reading and Writing, 22(1), 85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-008-9133-y

Talsma, K., Schüz, B., Schwarzer, R., & Norris, K. (2018). I believe, therefore I achieve (and vice versa): A meta-analytic cross-lagged panel analysis of self-efficacy and academic performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.015

The jamovi project (2020). Jamovi (1.6.3) [Computer software]. https://www.jamovi.org

Thomas, V., Muls, J., Backer, F. D., & Lombaerts, K. (2020). Middle school student and parent perceptions of parental involvement: Unravelling the associations with school achievement and wellbeing. Educational Studies, 46(4), 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2019.1590182

van der Lans, R. M., & Maulana, R. (2018). The use of secondary school student ratings of their teacher’s skillfulness for low-stake assessment and high-stake evaluation. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 58, 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.06.003

Wigfield, A., & Cambria, J. (2010). Students’ achievement values, goal orientations, and interest: Definitions, development, and relations to achievement outcomes. Developmental Review, 30(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2009.12.001

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Yoon, K. S., Harold, R. D., Arbreton, A. J. A., Freedman-Doan, C., & Blumenfeld, P. C. (1997). Change in children’s competence beliefs and subjective task values across the elementary school years: A 3-year study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.451

Wilkerson, D. J., Manatt, R. P., Rogers, M. A., & Maughan, R. (2000). Validation of student, principal, and self-ratings in 360° feedback® for teacher evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 14(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008158904681

Yao, E. S., Meissel, K., Bullen, P., Clark, T. C., Carr, A., Tiatia-Seath, P., Peiris-John, J., R., & Morton, S. M. B. (2022). Demographic discrepancies between administrative-prioritisation and self-prioritisation of multiple ethnic identifications. Social Science Research, 103, 102648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102648

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1016

Acknowledgements

This paper is a study extracted from the first author’s unpublished master’s degree thesis supervised by the second author. Data were obtained with permission from the Assessment Tools for Teaching and Learning (asTTle) project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, M., Brown, G.T.L. Secondary Students’ Perceptions of Teaching Quality and Teacher-Family Interaction: A Structural Equation Model. NZ J Educ Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-024-00342-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-024-00342-6