Abstract

Students often complain that the content of their studies is not practice-oriented enough because they do not recognize the importance of theory. This theory–practice problem has long been discussed in teacher education. Explicit research on religious education (RE) is only just beginning. This article tries to evince some connectors between theory and practice at the university level by means of a higher-education didactical model in the field of RE. For this purpose, a didactical course in RE called "learning workshop for religious didactics" in the curriculum of practical theology as a new format for university didactics was introduced. Within the framework of the accompanying research, both the teaching and the reflection on this teaching were recorded on video, and the students’ competences were analysed. This contribution aims to highlight specifically how this didactical model contributes to the increase in students’ theological and didactical skills and promotes their own activity and self-reflection in teaching lessons. Since the students’ teaching topic is "world religions", this model also contributes to their development in addressing religious plurality.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The goal of the didactical form is to combine theological content with preparation for students’ practice as religious education (RE) teachers in the future. Within the framework of this course, the students work on preparing a lesson and then conduct it at school. Through this process, students are challenged to deepen their theological knowledge as well as their knowledge of the didactics of RE and to combine the two.

Implementation of this concept was aided by Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung, a joint program launched in 2015 by the Federal Government and the German states. By 2023 the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) will have awarded a total of up to 500 million euros to support the continuous improvement of German teacher education at universities and schools of applied sciences. “Over 80% of the projects focus on the further development of their teacher training courses and curricula, especially regarding issues of diversity and inclusion. In addition to this, it seems important to note that all measures within the programme are research-oriented and data-based” (Federal Ministry of Education & Research, 2019, p. 2). The financial funds were used to establish a research assistant position (65%) to facilitate organization and scientific research for the project.

In order to understand the social context, this article first outlines how RE in schools and RE teacher training at university are organised in Germany. In teacher education, the relationship between theory and practice has been discussed for decades, and various models of practical relevance have been introduced in Germany. However, since school and university are different systems, the question is to what extent the university can respond to the call for school practice. The university contribution to the professionalisation of teachers lies primarily in the acquisition of reflective competence. Against this backdrop, the concept of the learning workshop at the Institute for Catholic Theology at the University of Koblenz is presented.

To ensure that the students understand the connection between theory and practice, the seminar was designed in such a way that the didactic theory is not only connected to the creation of a lesson plan, but also to its implementation in an RE class. The aim is for the students to recognise the indispensability of theological theories as well as didactical theories for their practice as teachers in reflecting on the draft and the lesson.

The first results of the accompanying research shed light on the students' subjective theories and prove that their understanding of theory changes as a result of the seminar.

2 Teacher training and RE in German schools

2.1 RE in Germany (cf. Kaupp, 2019)

In the German Constitution (Article 7, chapter 3), RE is identified is as an “ordinary school subject” that has to be taught “in accordance with the principles of the religious communities” (http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/gg/art_7.html). RE in German schools is organized through collaboration between the state and the religious communities and is determined according to res mixtae (joint responsibility).

Teachers normally have a university education including state examinations; teachers with an ecclesiastical education (parish worker, pastoral care staff) are also partially employed in the sphere of modern primary and secondary schools in some regions; however, they must also possess a state-issued teaching license. The local religious communities are generally responsible for teaching content. Religion teachers are assigned by the churches (Catholic: Missio; Protestant: Vocatio).

The school subject of RE is taught according to different beliefs and denominations, i.e., Catholic, Protestant, Jewish or Muslim. Increasingly often, this subject considers how interfaith co-operation between Catholics and Protestants may be established as well as how interreligious aspects could be incorporated. In Catholic-run schools Protestant RE is mostly also available. In some federal states (Bundesländer) Islamic RE is offered as well. Jewish and Orthodox Christian RE is also provided based on parental request.

Although RE is compulsory, pupils have the right to opt out of RE on the grounds of their right to freedom of religion. Pupils who do not participate in RE normally have to attend an alternative course on a subject such as Ethics, Practical Philosophy or Philosophy (according to the particular federal states).

2.2 Becoming a teacher of RE

In Germany, teacher training takes place in three basic phases, although the nature of the training differs slightly between federal states:

-

(a)

The focus of a course of studies at university comprises the chosen school subjects (usually two) as well as pedagogy/school pedagogy. While prospective primary school teachers mainly deal with theology in the bachelor phase of their studies, secondary school teachers study theology in the master phase as well. Students study the theology of their own religious denomination—however, the curriculums of both university and school education also address aspects of cooperation between denominations.

-

(b)

Within the study program, depending on the federal state, a longer school internship with teaching experience takes place. This is part of the following traineeship (Referendariat) over a period of 15–18 months. These individuals observe and, increasingly over time, take responsibility for the organization of lessons. In addition, they receive special didactic training according to state guidelines. Only after completion of this preparatory phase of practical teaching is it possible for teachers to receive a permanent teaching position.

-

(c)

Further training courses are also available for teachers. For teachers of RE, these are often offered by school departments of the dioceses in cooperation with state agencies.

3 The tension between theory and practical experience in teacher education

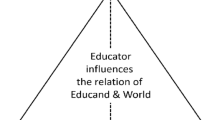

Pedagogy—and likewise RE—is always theory-led in relation to practice, but it is a mistake to believe that there is practice without theory. The question is rather at what level of abstraction theory is recognised as such. For the subjective everyday theories that determine our actions are usually not perceived as a theoretical foundation of practice. If practice is to be changed, the reflection must go beyond a theoretical foundation of everyday life. A practice that wants to do justice to the object or the persons cannot do without dealing with a theoretical background. The more aspects are taken into account, the more differentiated or abstract the theory inevitably becomes.

3.1 The call for a practical approach

Despite the mutual dependency of theory and practice, there is a call for more practical relevance in the teaching profession, in line with the motto: less learning for work and more learning at work, in order to produce less “inert knowledge” (cf. Artmann, 2019).

As a result, some federal states have introduced practical phases of study carried out over several months; other states offer regular seminars during the course of university studies whose goals are the observation of and reflection on teaching in situ.

In Rhineland-Palatina (where the University of Koblenz is located) the situation looks a bit different, because there exists no subject-specific practical training in subsidiary subjects, such as RE, for students in primary school education. This means that students may complete their studies without having acquired teaching or observation experience in RE classes. Students often do not recognise the connection between the contents of their studies and practice or later work as a teacher. This possibly corresponds to a social reality that usually assigns higher dignity to practice than to theory or only considers theory to be meaningful if it is as directly related to practice as possible. This situation makes the call for inclusion of “methods” and “practice” in theological studies all the more urgent.

3.2 Mediation of theory and practice during university studies

In terms of institutional theory, it should be noted that university and school are two different systems that function according to different logics. Therefore, it must be examined on which level a mediation of theory and practice is possible at all in the university. To this end, different forms of knowledge must first be distinguished: "receptive knowledge and routines as decision rules based on one's own experiences that can be applied in practice [and] reflective knowledge as theoretical knowledge used ex-post for the justification and reflection of actions (sense-making)" (Hedtke, 2000, p. 9).

Routines of teaching cannot be practised in studies and receptive knowledge can only be verified in teaching practice. But practical phases are for the most part teaching observations, i.e., the observation of the lessons of a trained teacher and not the students' own teaching practice.

Contrary to the general demand for more practice-oriented studies, recent research indicates that an increase in practical experience alone does not lead to a higher level of teaching professionality (cf. Artmann, 2019). A strong theoretical background is necessary for meaningful reflection on practical teaching experience. This is even more crucial given that didactic knowledge acquired during university studies is rarely put into practice in the RE classroom (cf. Englert, Henneke & Kämmerling, 2014, p. 12; Kohlmeyer & Reis, 2019), and teaching is often based on subjective, commonplace theoretical frameworks for quality teaching (Merkt, 2011, p. 17) that students are already aware of prior to their studies. In the “heat of the moment”, teachers act more intuitively than reflectively and tend to rely on episodic beliefs rather than on their formal knowledge (cf. Trautwein, 2013, p. 84; Wahl, 1991; Pajares, 1992, p. 312). The relation between intuition and action would be interesting. Reflected actions could become intuition that would be the best aim of this, but until now there exists hardly research on this.

This attitude of (prospective) teachers runs the risk that the experiences of their own school days become the benchmark and that they teach on the basis of subjective everyday theories about good teaching (which were already present before studying at university!) and thus consolidates receptive knowledge and routines that are neither always conducive to teaching nor to the students.

This is where university studies can come in by introducing reflective knowledge and thus promoting students' ability to reflect. Current research analyses the significance of subjective theories for teachers' actions and how these can be changed through reflection. (cf. Caruso & Hartels, 2020). Subjective theories (cf. Groeben & Scheele, 2020) possess an action-guiding or action-controlling function (cf. Dann, 1989). They influence the professional activity of teachers (Baumert et al., 2011) and thus have a significant effect on the planning and implementation of lessons (cf. Hirsch, 2017, p. 2).

In the context of the university studies of RE teachers, this research is still largely lacking. Therefore, the following example of teaching theory and practice is intended as a contribution to further research.

4 The learning workshop concept in the framework of Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung

The situation in Rhineland-Palatina has led to a completely new conception for the construction of a university seminar. This learning workshop is administrated by the Department of Practical Theology of the Institute for Catholic Theology at the University of Koblenz. The workshop curriculum is tied to the didactical and subject-matter specific knowledge seminar during the master’s program, and about 20 to 30 students regularly attend the seminar. The majority of the students are working towards becoming primary school teachers. The workshop is usually led by two lecturers.

The financial support secured through Offensive Lehrerbildung was also used for provision of so-called “learning kits” featuring learning material (items and symbols) relating to the five major world religions.

4.1 The theological content

Students in the primary school teacher programme study theology for only four semesters. Their interest is less in being an expert in theology (or another subject) than in being a teacher at a primary school. Moreover, not all of them grew up in an explicitly Christian environment and they often find the theological content very abstract. Since they do not do an internship in RE at school, they feel insecure. Many believe that the right teaching method is more important for their job than dealing with the subject content. For these reasons, the theological content was chosen in such a way that the significance of the content and subject didactics for their later professional practice is very clear to the students. As “different religions” is part of the subject matter in Catholic RE at all types of schools, this topic was chosen as a focus; it deals directly with religious heterogeneity and is thus theologically and didactically relevant. In order to be able to deal with "different religions" in class, professional knowledge of one's own religion as well as of other religions is necessary.

4.2 The religious-didactical learning workshop teaching concept

The didactic concept enables the interweaving of theory and practice, in that the students deal with subject matter as well as didactic approaches to the subject and have the opportunity to put these into practice in tandem settings during lessons at schools.

The didactic setting of the learning workshop consists of five successive phases:

-

(1)

The first is the theory and input-phase: Students must deepen their knowledge about world religions, for example Islam or Judaism, and deal with religious-didactical concepts of interreligious learning and their accompanying methods.

-

(2)

Independent working phase: During the second phase students work more independently and project oriented. They create theory-based material for the practical application in schools. Lecturers and professors provide the required support and advice along the way.

-

(3)

Presentation Phase: Students present their prepared teaching material and their lesson plan for RE during the seminar or independently in small groups and receive feedback from their fellow students and/or professors/lecturers.

-

(4)

Trial phase of the planned lesson with pupils in RE: Based on the provided feedback, students may make changes to their lesson plan. Prior to conducting the lesson via tandems, students visit the school in order to become acquainted with the class where the lesson will take place. The implemented lessons are then carried out and filmed.

-

(5)

Reflection on the trial phase: The students share their practical experience with fellow students and lecturers. Even more important, using the generated video material they reflect upon it with their professor during the subsequent review of the lesson, i.e., “debriefing” (cf. “Research” section).

4.3 The aims of the workshop

By means of the concrete task of preparing and conducting a lesson, the students should become aware of the allocation of theory and practice.

-

(a)

Combining theory and practice: Students are challenged to combine specialist knowledge and subject-specific didactics to prepare and conduct a lesson, and they must also work in teams. These conditions facilitate an in-depth examination of their role as teachers. In developing learning material, the connections between pedagogical, scientific, and didactic knowledge are strengthened (Wipperfürth & Klippel, 2016, pp. 190–191).

Learning workshops at other universities (for an overview cf. Reis, 2017, pp. 380–382) emphasize the importance of this combination. Mendl and Sitzberger (2016) conclude that an important element for the professionalisation of future teachers of RE can be recognized in the interplay between theoretical penetration and practical testing, as well as through reflection on the latter.

-

(b)

The proper way of dealing with religious plurality: Three reasons led to "world religions" as a topic:

-

The Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung presupposes that diversity is a cross-cutting issue, and in the field of religion this can be demonstrated by different religions.

-

Students have little knowledge about world religions. Especially knowledge about Judaism, which is a foundation of Christianity, is particularly necessary. Also, about Islam, since the number of Muslim children in Germany has increased significantly in recent decades.

-

The students are interested in this topic and see it as important, as it is also located in the RE curriculum at school.

-

The students grapple with the concepts of interreligious learning (cf. Leimgruber, 2007; Meyer, 2019; Sajak, 2018; Schambeck, 2013) and work according to the didactical approach “A Gift to the Child”, developed by Hull and Grimmitt at the University of Birmingham (Grimmitt, Grove, J., Hull et. al. 1991). This model attempts to address religious plurality through work with testimony and artefacts of foreign religions (Hull, 2000; Meyer, 2012, 2019; Sajak, 2005, 2010). The main goal is to accommodate younger pupils’ scope of experience and to enable “deepened and detailed encounter with an aspect or object of religious faith” (Hull, 2000, p. 155). Here the focus is on the examination of religious items, testimonies or numen of foreign religions, those which are characteristic of the life and faith of such a religion. Examples are the tone of the muezzin’s call to prayer, or a testimony such as the prayer rugs of Muslims, which serve as a special location for prayer (cf. Sajak, 2005, 2010).

Four stages are particularly important for the “A Gift to the Child” approach. These are (1) The Engagement Stage, (2) The Exploration Stage, (3) The Contextualization Stage, and (4) The Reflection Stage (Hull, 2000).

Based on this, pupils can, on the one hand, personally connect with the testimony, and on the other hand distance themselves from it after examining it thoroughly (Sajak, 2010; p. 48).

-

(b)

-

(c)

The correlation between concept and recipients: When preparing lessons, it is the task of the students to reflect on their design according to the model of elementarisation (cf. Schweitzer, 2011). This model serves to form a multilayered frame for the purposes of both planning and analysing RE processes. The model requires an intertwining analysis of the following aspects: (1) Elementary structures of the content; (2) Elementary experiences, as involved in the worlds of the tradition and the present; (3) Elementary accesses to attach to the pupils’ developmental and biographical experiences; (4) Elementary truths resulting from religious traditions and from the part of the children; and finally, (5) Elementary learning activities, which may support meaningful religious learning.

It is not only the theological content itself, but also this content’s relevance for one’s own faith that is important in this context. Furthermore, teachers must take this content’s anthropological significance as well as the developmental psychological and life-world conditions of the children into account. This model ensures that students acquire the necessary professional competence to present the subject matter appropriately with regard to its specific content.

-

(d)

Facilitation of reflective competence: Since reflective competence is a characteristic of the professionalism of teachers (cf. Roters, 2016, p. 46; cf. Roters, 2012; Helsper, 2001; Reis, 2009), it is important that students already practise their own abilities of professional and personal reflection during their studies (as opposed to first entering the teaching practice). The learning workshop offers numerous opportunities for reflection: while planning lessons, based on feedback from the seminar leader, the students, and teaching staff, and by reflecting on the overall process.

In order to explore the degree to which subject-specific, subject-didactic, and personal competences are reflected upon, special emphasis is placed on reflection about one’s own teaching. This focus is intended to foster student reflection on their own professional role and their behaviour in their interactions with pupils.

5 Research

In the following, approaches of the accompanying research are presented. Even though the research has not yet been completed, initial results can be shown from various perspectives.

5.1 Design research with a focus on learning processes

The various concepts of design research or design-based research cannot be described within the scope of this article (cf. an overview Prediger, Gravemeijer & Confrey, 2015, pp. 2–7). Prediger, Gravemeijer & Confrey discern two archetypes: “one that primarily aims at direct practical use, and one that primarily aims at generating theory on teaching learning processes” (2015, p. 7). Our model can be assigned to the first type. The aim is to correlate the content with the students' situation and to support their process of professionalisation as future RE teachers. The evaluations and the research results lead to a revision of the teaching concept and to change in teaching in the next cycle.

5.2 Methodology of research

The research is based on the one hand on the method of stimulated recall interviews (Messmer, 2014; cf. Calderhead, 1981) and on the other hand on the qualitative analysis of film material and interviews (cf. Mayring, 2000; 2019).

In order to investigate the students' learning process, students were filmed as they test their previously prepared lessons in the practice of teaching. Lessons were videotaped and interviews with the students were conducted. (On the significance of videography in teaching cf. Riegel, 2018). Due to the low number of participants, instruments of qualitative research were chosen.

Stimulated recall is an approach of reconstructive social research and is regarded as a suitable method to empirically record teachers’ invisible thought patterns. The research follows a two-step procedure. Interviews with the methodology of stimulated recall proved to be a particularly intensive form of reflection (Messmer, 2014; cf. Calderhead, 1981; Miotk 2020). For this purpose, the students are presented with their own videographed lesson. It serves as a stimulus to comment on their own behaviour. To do this, students independently press the pause button while watching the videos and explain their teaching actions. The explanations are recorded and form the basis for analysing the students' thought and action structures. It is thus possible to access the students' different moments of reflection and classify them into different dimensions of reflection. Moments of reflection are understood as a sensory unit from a cognitive process that attempts to structure or restructure an experience or problem (Aeppli & Lötscher, 2016).

The analysis of interviews and videographed lessons was processed with the methodological instruments of qualitative content analysis (Mayring, 2000). Qualitative content analysis defines itself “as an approach of empirical, methodological controlled analysis of texts within their context of communication, following content analytical rules and step by step models, without rash quantification” (Mayring, 2000, [5]). The central procedures of qualitative is the deductive and inductive development of categories step by step and die application of these categories on the interviews in order to work out different typologies of teacher’s acting. “The assignment of categories to text passages always remains an act of interpretation” (Mayring, 2019).

5.3 Research results of three master's theses

The first results are available in the context of master's theses, which were processed with the methodological instruments of Qualitative Content Analysis (Mayring, 2000).

The students’ theses are a testimony of how the approach of "research-based learning" (cf. Reis, 2017; Neuber, Paravicini & Stein, 2018) can be implemented into university didactics on the basis of final theses.

The interviews with students were analysed under different aspects:

-

(a)

Student perspectives on the relationship between theory and practice: On the basis of group interviews Lehmann (2018) analysed subjective theories on the relationship between theory and practice and their change through the seminar. She used four interviews to investigate the students' understanding of theory and practice. The analysis categories were "practice", "theory", and "theory–practice-interlocking". She was able to work out different forms of student understanding of theory and practice. Action- and process-oriented elements of the seminar are perceived as particularly practical (for example, learning with religious artefacts). Students understand "theory" as knowledge orientation (for example, the acquisition and production of texts), not the examination of didactic models. Although answers specifically distinguish between theory and practice, there are overlaps that mark the moment of overlap. Theory elements are only evaluated positively if they have practical relevance. The practical relevance is perceived as particularly positive ("theory that occurs like practice"). For the interrelationship to take place, a reflective approach to teaching practice is indispensable.

It is not only interesting for university didactics that a change has taken place among students. Due to experiences in the learning workshop and teaching, "theory" was evaluated more positively. It is possible that this university didactic setting supports a change in the subjective theories of the students through concrete implementation, which cannot be achieved through a theoretical examination of subject content and subject didactics.

-

(b)

Student assessments of themselves in terms of knowledge and competence: Also Trispel (2018) examined group interviews and examined the students' self-assessments of knowledge and competence with regard to the implementation of teaching. Above all, the students cited an increase in knowledge as relating to inter-religious questions and the design of a lesson. The students experienced their own competences in dealing with the pupils in an appropriate way in terms of content and didactics. As a dimension of self-critical reflection, the students identified weaknesses and problems in their time management and in the formulation of their work instructions to the students. Here it becomes clear that the seminar event alone only leads to a rudimentary acquisition of competence and that the students only make these a limited topic of discussion in the interviews.

-

(c)

The importance of starting the lesson in the "Gift to the child" concept: Theis (2018) analysed student behaviour in the role of teacher with the help of video recordings and their transcription. She examined "Lesson opening as a sensitive phase". The guiding question was how students succeed in implementing the first two phases of the Hull model (1. The Engagement Stage; 2. The Exploration Stage) and whether emotional involvement is actually achieved. Four lesson lead-ins, two in primary school classes (4th grade) and two in secondary school (9th grade), were examined. The result was that the didactic concept (as conceived by Hull) is suitable for primary school pupils in terms of developmental psychology but reaches its limits in older pupils. A redesign of the engagement and exploration stages is necessary. Woppowa (2016) has presented his thoughts on this issue: he precedes Hull's first phase with another phase in order to first establish a relationship between the students' living environment and the artefact to be worked on afterwards. A reflection on the effect of this approach would be possible after a further implementation.

5.4 Data structure analysis

Miotk, who worked as a lecturer for the project, is currently investigating which modes of action and thought structures can be reconstructed in the context of interreligious learning among students through the learning workshop in his PhD thesis. The research seeks to address the following questions:

-

Which didactic and scientific thought structures can be reconstructed in the students (are there any interactions)?

-

Which levels of reflection can be reconstructed in the students by working in the learning workshop?

-

What contribution can the learning workshop make to university religion teacher-in-training in order to do justice to the goal of a religion class characterized by religious plurality?

The results of the study are expected in 2023.

6 Conclusion

It can be stated that the seminar is an asset both in terms of combining theory and practice and in terms of exploratory learning. The commitment of the students, which is significantly higher than in other seminars, can be rated positively. The reason for this lies in the combination of theory and practice as well as the opportunity to test oneself professionally. However, the results of the reflection so far also show that insufficient content knowledge and didactic knowledge cannot be concluded in the context of a seminar event. It is to be hoped that the self-reflection of the students will lead them to recognize knowledge gaps and try to close them (cf. similar Davis, 2006).

Even in the context of the project described, it remains open whether and how practice ultimately affects professional self-understanding. Whether and how subjective theory interacts with practice cannot be researched within the framework of one semester. For this, long-term studies over the course of students’ university studies and ideally into their work as a teacher are necessary. Many aspects are still unexplored in empirical school research.

One possibility is to involve students themselves in research on school practice (cf. Reis, 2017, 282–285), as the present master’s theses have shown. This can help to acquire a reflective distance that sees teaching not only in action, but also enables it to be reflected upon from a "bird's eye view". In this way, the acquisition of reflective competence can be promoted, and the necessity of theory experienced, as practice is analysed against the background of subject-specific and subject-didactic knowledge. Overall, it is hoped that the format of a "learning workshop" will help students to combine theory and practice.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

References

Aeppli, J., & Lötscher, H. (2016). EDAMA—Ein Rahmenmodell für Reflexion. Beiträge Zur Lehrerinnen-Und Lehrerbildung, 34(1), 78–97.

Artmann, M. (2019). Es ist mir wichtig, dass die Studierenden sehen, dass Reflexion ohne Theorie ja gar nicht funktioniert. Epistemologische Zugänge von Hochschullehrenden zum Theorie-Praxis-Problem in der Lehrer*innenbildung. In Forum Qualitative Social Research 20. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/document/65016/1/ssoar-fqs-2019-3-artmann-Es_ist_mir_wichtig_dass.pdf

Baumert, J., Blum, W., & Kunter, M. (2011). Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Ergebnisse des Forschungsprogramms COACTIV. Waxmann.

Calderhead, J. (1981). Stimulated recall: A method for research on teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 51, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1981.tb02474.x

Caruso, C., & Harteis, C. (2020). Inwiefern können Praxisphasen im Studium zu einer Theorie-Praxis-Relationierung beitragen? Implikationen für die professionelle Entwicklung angehender Lehrkräfte. In K. Rheinländer & D. Scholl (Eds.), Verlängerte Praxisphasen in der Lehrer*innenbildung. Konzeptionelle und empirische Aspekte der Relationierung von Theorie und Praxis (pp. 58–73). Klinkhardt.

Dann, H. D. (1989). Subjektive Theorien als Basis erfolgreichen Handelns von Lehrkräften. Beiträge Zur Lehrerinnen- Und Lehrerbildung, 7(2), 247–254.

Davis, E. A. (2006). Characterizing productive reflection among preservice elementary teachers: Seeing what matters. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.11.005

Englert, R., Hennecke, E., & Kämmerling, M. (2014). Innenansichten des Religionsunterrichts. Fallbeispiele – Analysen – Konsequenzen. Kösel.

Federal Ministry of Education and Research. (2019). Interim results of the “Qualitätsoffensive Lehrerbildung”. Initial findings from research and practice. BMBF.

Grimmitt, Mi. H., Grove, J., Hull, J., & Spencer, L. (1991). A Gift to the Child. Religious Education in the Primary School. Teachers’ Source Book. Simon & Schuster.

Groeben, N., & Scheele, B. (2020). Forschungsprogramm Subjektive Theorien. In G. Mey & K. Mruck (Eds.), Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie. Springer.

Hedtke R. (2000). Das unstillbare Verlangen nach Praxisbezug - Zum Theorie-Praxis-Problem der Lehrerbildung am Exempel Schulpraktischer Studien. Retrieved February 20, 2022, from https://www.sowi-online.de/journal/2000_0/hedtke_unstillbare_verlangen_nach_praxisbezug_zum_theorie_praxis_problem_lehrerbildung_exempel.html

Helsper, W. (2001). Praxis und Reflexion—die Notwendigkeit einer „doppelten Professionalisierung“ des Lehrers. Journal Für LehrerInnenbildung, 1(3), 7–15.

Hirsch, J. (2017). Subjektive Theorien zum Lehren und Lernen von Lehramtsstudierenden vor und nach der ersten Fachdidaktik-Lehrveranstaltung. In die hochschullehre. Interdisziplinäre Zeitschrift für Studium und Lehre (p. 3). Retrieved October 10, 2022, from http://www.hochschullehre.org/wp-content/files/diehochschullehre_2017_hirsch.pdf

Hull, J. (2000). Die Gabe an das Kind. Ein neuer pädagogischer Ansatz. In J. Hull (Ed.), Glaube und Bildung. Ausgewählte Schriften (pp. 141–164). Kik.

Kaupp, A. (2019). Catholic Religious Education in Germany and the Challenges of Religious Plurality. In M. T. Buchanan & A. Gellel (Eds.), Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools, Volume II: Learning and Leading in a Pluralist World Singapore (pp. 575–587). Springer.

Kohlmeyer, T., & Reis, O. (2019). Vorsehung–Zufall–Schicksal? Die fachdidaktische Lehrstelle als Problem der unterrichtlichen Handlungssteuerung. In Religionspädagogische Beiträge (81) (pp. 99–110).

Leimgruber, S. (2007). Interreligiöses Lernen. Kösel.

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

Mayring, P. (2019). Qualitative content analysis: Demarcation, varieties, developments. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. https://doi.org/10.17619/fqs-20.3.3343

Mendl, H., & Sitzberger, R. (2016). Lernwerkstatt Religionsunterricht. Theorie-Praxis-Verschränkung konkret. Paradigma—Beiträge aus Forschung und Lehre aus dem Zentrum für Lehrerbildung und Fachdidaktik, 8. Retrieved from https://ojs3.uni-passau.de/index.php/paradigma/article/view/65/70

Merkt, M. (2011). Schlussbericht ProfiLe Hamburg. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://docplayer.org/9468973-Schlussbericht-zu-projekt-profile-nr-01ph08025-projektleitung-und-koordination.html

Messmer, R. (2014). Stimulated recall as a focused approach to action and thought processes of teachers. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.1.2051

Meyer, K. (2012). Zeugnisse fremder Religionen im Unterricht. Weltreligionen im englischen und deutschen Religionsunterricht. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Meyer, K. (2019). Grundlagen interreligiösen Lernens. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Miotk, J. (2020). Dimensions of reflection—Stimulated recall as a method for teaching training. In C. Juchem-Grundmann & S. Wunderlich (Eds.), The interplay of theory and practice in teacher education. Peter Lang.

Neuber, N., Paravicini, W. D., & Stein, M. (Eds.) (2018). Forschendes Lernen—The wider view. Eine Tagung des Zentrums für Lehrerbildung der Westfälischen Wilhelms-Universität Münster vom 25. bis 27.09.2017. (Schriften zur allgemeinen Hochschuldidaktik, 3). Münster: WTM.

Pajares, F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62, 307–332.

Prediger, S., Gravemeijer, K., & Confrey, J. (2015). Design research with a focus on learning processes: an overview on achievements and challenges. ZDM Mathematics Education, 47, 877–891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-015-0722-3

Reis, O. (2017). Forschendes Lernen in der Theologie. In H. A. Mieg & J. Lehmann (Eds.), Forschendes Lernen. Wie die Lehre in Universität und Fachhochschule erneuert werden kann (pp. 377–386). Campus.

Reis, O. (2009). Durch Reflexion zur Kompetenz—Eine Studie zum Verhältnis von Kompetenzentwicklung und reflexivem Lernen an der Hochschule. In R. Schneider, B. Szczyrba, U. Welbers, & J. Wildt (Eds.), Wandel der Lehr-und Lernkultur: 40 Jahre Blickpunkt Hochschuldidaktik (pp. 100–120). Bertelsmann.

Riegel, U. (2018). Video analysis. Opening the black box of teaching religious education. In F. Schweitzer & R. Boschki (Eds.), Researching religious education. Classroom processes and outcomes (pp. 117–129). Waxmann.

Roters, B. (2012). Professionalisierung durch Reflexion in der Lehrerbildung. Eine empirische Studie an einer deutschen und einer US-amerikanischen Universität. Waxmann.

Roters, B. (2016). Reflexionskompetenz als Merkmal der Professionalität von Lehrkräften. In Bundesarbeitskreis der Seminar- und Fachleiter (Ed.). Zeitschrift Seminar, 1, 46–57.

Sajak, C. P. (2005). Das Fremde als Gabe begreifen. Auf dem Weg zu einer Didaktik der Religionen aus katholischer Perspektive. Lit Verlag.

Sajak, C. P. (2010). Kippa, Kelch, Koran. Interreligiöses Lernen mit Zeugnissen der Weltreligionen. Ein Praxisbuch. Kösel.

Sajak, C. P. (2018). Interreligiöses Lernen. (Theologie kompakt). Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Schambeck, M. (2013). Interreligiöse Kompetenz. Basiswissen für Schule, Ausbildung und Beruf. UTB.

Schweitzer, F. (2011). Elementarisierung im Religionsunterricht. Erfahrungen, Perspektiven, Beispiele, mit weiteren Beiträgen von Karl Ernst Nipkow u.a., 3. Vandenhoek & Ruprecht.

Trautwein, C. (2013). Struktur und Entwicklung akademischer Lehrkompetenz. In J. Wildt & M. Heiner (Eds.), Professionalisierung der Lehre Perspektiven formeller und informeller Entwicklung von Lehrkompetenz im Kontext der Hochschulbildung (pp. 83–131). Bertelsmann.

Wahl, D. (1991). Handeln unter Druck. Der weite Weg vom Wissen zum Handeln bei Lehrern, Hochschullehrern und Erwachsenenbildnern. Deutscher Studien-Verlag.

Wipperfürth, M., & Klippel, F. (2016). Brennpunkt Lernmaterial: Praxisnahe fachdidaktische Lehre in der Lernwerkstatt. In S. Anselm & M. Janka (Eds.), Vernetzung statt Praxisschock. Konzepte, Ergebnisse, Perspektiven einer innovativen Lehrerbildung durch das Projekt Brücksteine (pp. 185–196). Edition Ruprecht.

Woppowa, J. (2016). Inter- und intrareligiöses Lernen. Eine fundamentaldidaktische und lernortbezogene Weiterentwicklung des Lernens an Zeugnissen der Religionen. In C. Gärtner & N. Bettin (Eds.), Interreligiöses Lernen an außerschulischen Lernorten. Empirische Erkundungen zu didaktisch inszenierten Begegnungen mit dem Judentum (pp. 27–44). Lit Verlag.

Master thesis

Lehmann, S. (2018). Studienwerkstatt Religionsdidaktik – Auswertung des Konzeptes der Studienwerkstatt am Beispiel interreligiösen Lernen im Religionsunterricht der Grundschule in Hinblick auf die Verknüpfung von Theorie und Praxis. (unpublished)

Theis, T. (2018). Der Unterrichtseinstieg als sensible Phase. Eine qualitative Studie zum Lernen an fremden Religionen im katholischen Religionsunterricht. (unpublished)

Trispel, L. (2018). Wissen und Kompetenzen von Lehramtsstudierenden der Katholischen Theologie. Eine qualitative Inhaltsanalyse der Lernwerkstatt Religionsdidaktik zum Thema Weltreligionen. (unpublished)

Funding

The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest:

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest. The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaupp, A. Theory and practical experience as two sides of a coin. j. relig. educ. 71, 77–89 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-022-00193-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-022-00193-7