Abstract

We compare standard (laboratory) and non-standard (field) subject pool behavior in an extensive form public goods game with random punishment. Our experimental investigation is motivated by real-world ‘Activists’ encouraging public goods provision by firms; an activity known as corporate social responsibility. We find that relative to laboratory subjects, activists in Mumbai are more willing to settle at the Nash equilibrium of the game (which entails increased provision of public goods) and are more willing to punish non-cooperative firm behavior even if such punishments hurt their own payoffs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Bayraktar (2019) demonstrates that threshold and/or a volatility effects might explain the low effectiveness of public investment in sub-Saharan Africa: Public investment might only spur economic growth if it is provided in sufficient volume and at stable levels over time. By inducing firms to increase public investment, Activists could increase the overall effectiveness of investment to a level sufficient to spur growth.

Kitzmueller and Shimshack (2012) define CSR as any voluntary social activity that causes observable behavior or output by firms exceeding levels set by legal regulation.

Section 135 of India's Companies Act of 2013 requires firms that exceed specific size/profit thresholds to spend a minimum of 2% of their net profit on CSR (or explain why they are unable to do so). Thus, firms are required to contribute to public goods provision; NGO activists might attempt to increase the firms’ provisioning beyond the mandatory amount.

This organization is a social movement/youth empowerment oriented network; detailed information is available at https://brmworld.org/.

Benabou and Tirole (2010) identify three CSR channels: a long-term perspective on profitability adopted by firms who engage in CSR versus those who do not; that firms engage in CSR due to shareholder concerns; and that firms engage in CSR due to the concerns of corporate insiders and managers.

Zheng (2019) explains non-organized boycott activities and their effects on CSR provision in a war of attrition framework, providing additional motivation for our analyses.

Hayakawa (2017) describes a dynamic game analyzing entry/exit in common pool resource problems.

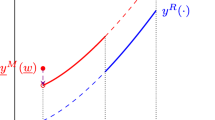

Because endogenous probabilities determine equilibrium in Baron (2001), it is not possible to design an experiment that exactly replicates his model. Additionally, given our focus on standard vs. non-standard subject pool behavior, we chose instead to experimentally test a main tension of CSR behavior.

Both the established laboratory and field subject pools respond as predicted to variation in the MPCR of the VCM game.

A differentiation of activists’ operations exists, but scholars emphasize that activists’ operations may not constitute institutional change (den Hond and de Bakker 2007). We do not expect fundamental changes in the structure of our experiment to result from activists. Instead, we find consequences of the actions of players assigned the Activist role to determine payoffs for all players.

In a VCM, (\(i\)) individuals must decide how to allocate their endowments of points (\(E_{i}\)) between a hypothetical public good and a private good (\(C_{i}\)). The payoff for individual \(i\) is given by \(E_{i} - C_{i} + {\text{MPCR} }\times {\text{Total contributions}}\).

See also Normann and Rau (2015).

All standard subject pool sessions were conducted at the Social Science Experimental Laboratory (SSEL) at New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD).

Subjects do not know that the tasks have been designed to have no variation in endowments; in this part of our design, we are merely looking for subjects to have perfect real effort task scores.

See the Appendix for screenshots of the experimental software.

Subjects had to successfully answer quiz questions about the VCM and stage game prior to commencing the games to ensure they understood how the games functioned.

The CSR analog behind this is that once the Firm rejects the Activist’s demand, the Activist attempts a boycott against the Firm’s products.

Some “computer labs” were no more than converted corrugated tin roof shacks that provided internet and computing access for local communities. Photographs of lab-in-the-field sites available in the Appendix.

Some ‘Activist’ subjects asked why they were asked survey questions at the end of the experiment; the non-responses are likely caused by privacy concerns, despite our assurances that the responses would be treated confidentially.

The code for the laboratory and field experiments and replication data are available upon request.

We chose to create the VCMRATE variable since there was slightly more variation in RET scores amongst field subjects. Thus, the VCMRATE variable “deflates” contributions by earned endowments.

References

Bagnoli, M., & Watts, S. G. (2003). Selling to socially responsible consumers: Competition and the private provision of public goods. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 12(3), 419–445.

Bansal, P., Jiang, G., & Jung, J. (2015). Managing responsibly in tough economic times: Strategic and tactical CSR During the 2008–2009 global recession. Long Range Planning, 48(2), 69–79.

Baron, D. (2001). Private politics, corporate social responsibility, and integrated strategy. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 16(3), 7–45.

Bartling, B., Weber, R. A., & Yao, L. (2015). Do markets erode social responsibility? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218.

Bayraktar, N. (2019). Effectiveness of public investment on growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Eurasian Economic Review, 9, 421–457.

Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2010). Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica, 77(305), 1–19.

Blanco, E., Haller, T., & Walker, J. M. (2018). Provision of environmental public goods: Unconditional and conditional donations from outsiders. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 92, 815–831.

Bland, J., & Nikiforakis, N. (2015). Coordination with third-party externalities. European Economic Review, 80, 1–15.

Bolle, F., Breitmoser, Y., & Schlächter, S. (2011). Extortion in the laboratory. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 78(3), 207–218.

Briscoe, F., Gupta, A., & Anner, M. (2015). Social Activism and practice diffusion: How activist tactics affect non-targeted organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(2), 300–332.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 817–869.

Charness, G., -Reyes, R., & Sanchez, A. (2016). The effect of charitable giving on workers’ performance: Experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 131, 61–74.

Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., & Wickens, C. (2016). oTree-an open source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 9, 88–97.

Cox, C. A., & Stoddard, B. (2018). Strategic thinking in public goods games with teams. Journal of Public Economics, 161, 31–43.

den Hond, F., & de Bakker, F. (2007). Ideologically motivated activism: How activist groups influence corporate social change activities. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 901–924.

Fischbacher, U., & Gachter, S. (2010). Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public goods experiments. American Economic Review, 100(1), 541–556.

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S., & Fehr, E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Economics Letters, 71(3), 397–404.

Gächter, S., Nosenzo, D., Renner, E., & Sefton, M. (2010). Sequential vs. simultaneous contributions to public goods: Experimental evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 94(7–8), 515–522.

Groza, M., Pronschinske, M., & Walker, M. (2011). Perceived organizational motives and consumer responses to proactive and reactive CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(4), 639–652.

Hayakawa, H. (2017). The tragedy of the commons: The logic of entry and the dynamic process under two scenarios. Eurasian Economic Review, 7, 311–328.

Houser, D., Xiao, E., McCabe, K., & Smith, V. (2008). When punishment fails: Research on sanctions, intentions and non-cooperation. Games and Economic Behavior, 62(2), 509–532.

Kitzmueller, M., & Shimshack, J. (2012). Economic perspectives on corporate social responsibility. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(1), 51–84.

Koppel, H., & Regner, T. (2014). Corporate social responsibility in the work place: Experimental evidence from a gift-exchange game. Experimental Economics, 17(3), 347–370.

Nikiforakis, N., Oechssler, J., & Shah, A. (2014). Hierarchy, coercion, and exploitation: An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 97, 155–168.

Normann, H.-T., & Rau, H. (2015). Sequential contributions to step-level public goods: one versus two provision levels. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 59(7), 1273–1300.

Walker, J., & Halloran, M. (2004). Rewards and sanctions and the provision of public goods in one-shot settings. Experimental Economics, 7(3), 235–247.

Zheng, Y. (2019). Non-organized boycott: alliance advantage and free riding incentives in uneven wars of attrition. Eurasian Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-019-00138-w.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dave, C., Hamre, S., Kephart, C. et al. Subjects in the lab, activists in the field: public goods and punishment. Eurasian Econ Rev 10, 533–553 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-020-00144-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-020-00144-3