Abstract

Cognitive impairments contribute to difficulty obtaining employment for people with severe mental illness (SMI). We describe an evaluation of a program, Employ Your Mind (EYM), which integrates cognitive remediation with vocational rehabilitation to improve cognitive skills and psychosocial outcomes relevant to employment. Participants with SMI were referred to WISE Employment and completed the six-month EYM program. Assessments of psychosocial functioning, cognition and vocational data were collected at baseline and completion, and additional vocational outcomes were collected at 12-month follow-up. Psychosocial functioning and cognition were compared pre- and post-EYM and vocational outcomes were compared for the year prior to EYM and for the 12-month follow-up for program completers. Thirty-two participants commenced the EYM program and 21 (65.6%) completed it. Completers reported significant improvements in mental wellbeing, quality of life and enhanced overall perceived working ability. Participants also demonstrated significantly enhanced speed of processing. Of the 15 participants who reported vocational outcomes, four (26.6%) were engaged in competitive paid employment in the year prior to EYM commencement and eight (53.3%) in the year following EYM commencement. The results indicate that EYM helps improve cognitive performance, psychosocial outcomes, and work readiness in people with SMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe mental illnesses (SMIs) often lead to psychosocial disability, affecting an individual’s capacity to interact with others, work, and lead ‘a contributing life’ [25]. Cognitive impairments associated with SMIs can include difficulties with memory, concentration, organised thinking, planning, problem-solving, and goal setting [13, 29]. On average, people with psychotic disorders score 1.6 standard deviations below the general population in cognitive ability,this has a significant impact on everyday functioning and ability to undertake everyday activities [23].

The majority of people with SMIs want to work and contribute to society [23]. The mental health benefits of work for this population are well established. A systematic meta-review by Modini et al. [22] found that ‘the role work can play in facilitating recovery from an illness and enhancing mental well-being needs to be highlighted and promoted more widely’ (p. 331). In addition to an income, identified mental health benefits of work for people with SMI include: enhanced structured daily activities, improved self-esteem, feeling a useful member of the community, and provision of social opportunities [9, 22]. Work remains elusive for many, however. Australian data show that only one in four people with a psychosocial disability (25.7%) are employed, compared with 80.3% of those without disability [1]. An important contributing factor to this may be that many modern work roles make complex demands on cognitive and social skills, which are often impaired in individuals with SMIs [23]. Psychosocial rehabilitation programs, particularly those focusing on vocational goals, need to address this issue.

The Cognitive Remediation Experts Working Group [7] define cognitive remediation (CR) as an ‘intervention targeting cognitive deficit (attention, memory, executive function, social cognition or meta-cognition) using scientific principles of learning with the ultimate goal of improving functional outcomes. Its effectiveness is enhanced when provided in a context (formal or informal) that provides support and opportunity for extending to everyday functioning'. CR has been shown to be effective in improving cognitive function in people with SMIs [40]. A review of CR interventions in individuals with SMIs found that computer-based CR exercises are equally as effective when delivered via computer or clinician, with computer-based CR more easily standardised [10]. Vocational rehabilitation can improve everyday living and employment-related skills [3, 14, 19] with the suggestion that the future of CR for individuals with SMI lies in ‘developing effective programs that combine CR and psychosocial and vocational rehabilitation’ [10, p. 4].

The EYM program incorporates core features of CR as identified by Bowie et al. [4]: use of qualified cognitive remediation therapists,cognitive exercise aimed at improving cognitive functioning; procedures to develop problem-solving strategies, and procedures to facilitate transfer to real-world functioning. A recent meta-analysis by Lejeune et al. [17] concluded that programs that incorporate bridging sessions and strategy coaching are ‘more cognitively potent’. The EYM program also incorporates lessons gleaned from the evaluation of the EYM pilot program [21], including use of validated assessments to measure cognitive and psychosocial outcomes, collection of vocational outcomes, implementation by a dedicated multi-disciplinary team of mental health professionals and longer-term follow-up of participant outcomes.

The current study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of EYM in improving cognitive skills and psychosocial outcomes relevant to employment and community engagement in individuals with SMIs.

Methods

Overview and Design

EYM was delivered by WISE Employment, a not-for-profit employment services provider in Victoria, Australia. The EYM team consists of three masters-qualified occupational therapists, a counsellor, Indigenous mental health worker, and a mental health peer support worker. Evaluation was conducted by St Vincent’s Hospital Mental Health Service. Recruitment took place between March 2019 and October 2020. The study was granted ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, and all procedures were in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Participants were referred to the EYM program by mental health and other community support services. They were eligible to complete the program if they were over the age of 18, had a diagnosis of a SMI (including affective disorders, psychotic disorders, or PTSD), had an employment or other vocational goal, and were able and willing to participate in groups. Exclusion criteria were: (1) unable to attend sessions at the service and (2) lack of basic English literacy.

Program Outline

EYM was originally designed by Fife Employment Access Trust in Scotland. The six-month program involves one to two sessions per week, combining computer-based CR exercises, individual project work, group reflection/ discussion, bridging exercises, and a work experience placement (see Table 1 for program outline). Bridging exercises, as described by Medalia and Bowie [20], are ‘therapist-led verbal discussion and skills-training activities that help cognitive remediation participants apply what is learned on the restorative exercises to cognitive performance in everyday life’ (p. 66). The CR program used was Happy Neuron [12], a computer-based cognitive training module, which includes exercises on spatial memory, verbal memory, visual memory, executive function, visual and auditory attention, and processing speed. COVID-19 restrictions were introduced in Melbourne, Australia, while recruitment was underway, leading to transitioning of the delivery to online,this was readily effected and did not unduly disrupt program delivery.

Outcome Measures

Basic demographic and clinical information were collected. Participants self-reported their primary mental health diagnosis, which were classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [39]. Assessments of psychosocial functioning (Table 2) and cognition (Table 3) were collected at commencement (baseline), completion, and at 12-month follow-up from program commencement. Vocational data were collected at program commencement and at 12-month follow-up from program commencement.

Psychosocial Outcome Measures

Table 2. details the psychosocial outcomes that were collected.

Cognitive Outcome Measures

Cognitive assessments were selected from the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) [27] for which normative data have been established [16]. Eight of the ten MCCB tests were included as sufficient to evaluate five key neurocognitive domains (see Table 3). The excluded tests were the Continuous Performance Test, Identical Pairs (CPT-IP) [8] and the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test, Revised (BVMT-R) [2]. This selection reduced assessment burden on participants and allowed for more extensive assessment of psychosocial outcomes.

Raw scores for each MCCB test and domain were converted to age and gender corrected t-scores using the MCCB scoring program. Testing was conducted by masters-level examiners who received extensive training in administration of the MCCB using video and group training sessions under the guidance of a psychiatrist. Quality assurance included periodic checks on MCCB administration and scoring practices.

Vocational Outcome Measures

Employment and other vocational data for the preceding 12-months were collected to provide an overview of activity over two time periods: the year prior- and the year post-EYM commencement. Participants were asked to provide details of (1) competitive paid employment, (2) informal paid employment (for example, babysitting), (3) voluntary unpaid work, and (4) study and educational engagement over the previous 12-months.

Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM, SPSS Statistics Version 25). Descriptive and frequency analyses were used to explore demographic and clinical characteristics. Data were assessed for normality and paired t-tests were used to compare cognitive and psychosocial parameters between baseline and post-program for the participants who completed the EYM program. Between-group comparisons of vocational outcomes were conducted using Fisher’s exact test. For all analyses, Bonferroni corrections were applied to account for multiple comparisons and significance was set at p < 0.003 for psychosocial outcomes and p < 0.006 for cognitive outcomes. Missing values were excluded on a list-wise basis.

Results

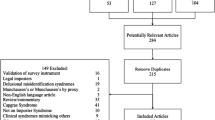

Thirty-two participants commenced the EYM program. Table 4 provides demographic and clinical characteristics of the entire sample at baseline.

Twenty-one participants completed the four phases of the EYM program: 15 (71.4%) completed the program in person at WISE employment and 6 (28.6%) completed the program remotely via video teleconferencing due to COVID-19 restrictions. Of the 32 participants recruited, 11 (34.3%) withdrew prior to completion of the program: one (3.1%) due to mental ill health; one (3.1%) relocated interstate; two (6.25%) discontinued due to COVID-19; three (9.4%) were lost to follow-up, and four (12.5%) commenced employment or study. (Note: the two who discontinued due to COVID-19 rejoined the program when restrictions were relaxed but after completion of the evaluation).

Psychosocial Outcomes

Psychosocial and cognitive outcomes are reported for the 21 participants who completed the EYM program. Comparison of psychosocial outcomes between baseline and post-program are reported in Table 5.

Participants reported significant increases in positive mental wellbeing (WEMWBS), mental health QoL and overall QoL, as well as significantly increased self-awareness, interests and values, and enhanced overall perceived working ability (as assessed by the DWA). Improvements were also seen in additional subscales of the AQoL (independent living, relationships, coping) and DWA (physical ability, organisation and problem solving, communication), increased work and social adjustment, as well as increased self-reported recovery, but these did not remain significant after correction for multiple comparisons.

Cognitive Outcomes

Participants completed an average of 13.05 ± 10.66 computer-based CR hours over the course of the EYM program. Cognitive outcomes are reported below in Table 6 for the participants who completed the EYM program. Participants also engaged in group discussion, reflection, strategy coaching, and bridging exercises. It is important to note that while this additional activity is considered instrumental in facilitation of transfer to real-world functioning, the time spent engaged in these activities was not collected as part of the evaluation.

A significant increase in speed of processing was observed in the Category Fluency Test between baseline and post-EYM. There were also increases in verbal learning (HVLT-R), working memory (LNS), reasoning and problem solving (Mazes) and social cognition (MSCEIT), yet these did not remain significant after correction for multiple comparisons.

Vocational Outcomes

Fifteen participants completed assessment of vocational outcomes for the preceding year at baseline and 12-months following EYM commencement (see Table 7).

There was no significant change in the proportion of participants engaged in vocational activities between the year prior to and year following EYM commencement. The proportion of participants in competitive employment doubled from four (26.6%) to eight (53.3%) in the year following EYM commencement.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the Employ Your Mind (EYM) program in improving cognitive skills and psychosocial outcomes relevant to employment and community engagement in individuals with SMIs. The evaluation incorporated the recommendations made in the pilot EYM evaluation [21] including the utilisation of a selection of tests from the MCCB, the inclusion of validated assessments of mental well-being and quality of life, collection of vocational outcomes and longer term follow up. In addition, the program was delivered by a team directly employed by WISE Employment, which allowed for closer adherence to the core features of CR as identified by Bowie et al. [4] through ongoing training, professional development and supervision. Under these more stringent conditions, our study confirmed the positive results of the pilot program evaluation.

There were significant improvements in category fluency—an assessment of speed of processing—and measures of mental well-being, quality of life, and perceived working ability, despite the small sample size and limited statistical power. Moreover, improvements in these outcomes demonstrated medium to large effect sizes. There were trends towards improvement across all psychosocial measures (mental wellbeing, quality of life, recovery, work and social adjustment, perceived working ability) and several cognitive domains including speed of processing, verbal learning, working memory, reasoning and problem solving, and social cognition. The trend towards more competitive employment—despite the impact of a strict and extended COVID-19 lockdown in Melbourne during 2020—is also encouraging. These results are consistent with increasing evidence that CR has valuable and sustained benefits for people with SMI with vocational goals [31, 36, 42].

It is noteworthy that the evaluation results were obtained with an average time of 13.05 ± 10.66 h engaged in computer-based CR (using the Happy Neuron program) over the course of the EYM intervention. This amount of time is significantly less than the recommended hours (20–40 h) previously reported in the literature [4]. The Expert Working Group on Cognitive Remediation advised that 'intensive training is ideal to produce meaningful effects' whilst acknowledging there are as yet no published comparative 'dosing' studies of CR [4, p. 51]. Dosage captured by the Happy Neuron program does not include the valuable time spent engaged in group and individual strategy coaching, bridging, and reflection/ discussion, all of which are key components of CR used in the EYM program. In subsequent evaluations, it will be important to document this time in more detail so that dosage can be more accurately reported. The length of intervention, however, is consistent with other CR programs. A meta-analysis by Wykes et al. [41] found the average length of treatment to be 32.2 h provided across 16.7 weeks. More recently, in their meta-analysis of CR for negative symptoms of schizophrenia, Cella et al. [6] identified effective programs provided 24 to 100 h of therapy time across periods ranging from 12 weeks to two years. EYM provides 63 h of individual and group intervention and up to 20 h of volunteer work experience over the course of six months. These results are consistent with other research that demonstrates improvement in cognitive and psychosocial functioning, when provided in the context of rehabilitation [19, 41]. Further investigation would establish if positive outcomes might be obtained with fewer hours of computer based CR activities integrated into vocational rehabilitation.

Limitations

A particular challenge was the facilitation of EYM during the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions in 2020, which were strict and long-lasting in Melbourne. With recruitment affected for six months and no face-to-face contact, program delivery and the ability of participants to gain employment were all impacted. This was mitigated by adaptation of the program to telepractice (using computer-based CR and videoconferencing). Despite the effect of workplace restrictions, it is notable that a number of participants were nevertheless able to find employment. Future evaluation of the program should include a larger sample size, controlled design, and investigation of the effect of dosage, particularly in the context of a vocational rehabilitation setting.

Conclusion

The results of this evaluation strengthen confidence in the value of the EYM program to improve cognitive and psychosocial outcomes related to vocational and community engagement. A larger trial to improve understanding and effectiveness of the program, especially relating to the CR dose–effect relationship, is warranted.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Psychosocial disability. 2020. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/psychosocial-disability. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Benedict RHB. Brief visuospatial memory test—revised: professional manual. Odessa, Fla: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1997.

Bowie CR, McGurk SR, Mausbach B, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. Combined cognitive remediation and functional skills training for schizophrenia: effects on cognition, functional competence, and real-world behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:710–8.

Bowie CR, Bell MD, Fiszdon JM, Johannesen JK, Lindenmayer JP, McGurk SR, Medalia AA, Penadés R, Saperstein AM, Twamley EW, Ueland T, Wykess T. Cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: an expert working group white paper on core techniques. Schizophr Res. 2020;215:4.

Brandt J, Benedict RHB. The hopkins verbal learning test—revised: professional manual. Odessa, Fla: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2001.

Cella M, Preti A, Edwards C, Dow T, Wykes T. Cognitive remediation for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;52:43–51.

Cognitive Remediation Experts Working Group (CREW), April 2010. Florence.

Cornblatt BA, Risch NJ, Faris G, Friedman D, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. The continuous performance test: identical pairs version (CPT-IP): I: new findings about sustained attention in normal families. Psychiatry Res. 1988;26(2):223–38.

Fossey EM, Harvey CA. Finding and sustaining employment: a qualitative meta-synthesis of mental health consumer views. Can J Occup Ther. 2010;77:311–22. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2010.77.5.7.

Galletly C, Rigby A. An overview of cognitive remediation therapy for people with severe mental illness. ISRN Rehabil. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/984932.

Gold JM, Carpenter C, Randolph C, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Auditory working memory and wisconsin card sorting test performance in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(2):159–65.

Happy Neuron. HappyNeuron Pro. 2018. www.happyneuronpro.com. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Heinrichs R, Zakzanis K. Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology. 1998;12:426–45.

Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, Carter M, Greenwald D, Pogue-Geile M, Garrett A. Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):866–76.

Keefe RS. Brief assessment of cognition in Schizophrenia BACS. Durham: Duke University Medical Center; 1999.

Kern RS, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, Marder SR. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 2: co-norming and standardization. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):214–20.

Lejeune JA, Northrop A, Kurtz MM. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: efficacy and the role of participant and treatment factors. Schizophr Bull. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbab022.

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. Mayer-Salovey-Caruso emotional intelligence test (MSCEIT) user’s manual. Toronto: MHS Publishers; 2002.

McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–802.

Medalia A, Bowie CR. Cognitive remediation to improve functional outcomes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Miles A, Crosse C, Jenkins Z, Moore G, Fossey E, Harvey C, Castle D. “Employ Your Mind”: a pilot evaluation of a programme to help people with serious mental illness obtain and retain employment. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;29(1):57–62.

Modini M, Joyce S, Mykletun A, Christensen H, Bryant RA, Mitchell PB, Harvey SB. The mental health benefits of employment: results of a systematic meta-review. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;4(4):331–3.

Morgan VA, Waterreus A, Jablensky A, Mackinnon A, McGrath JJ, Carr V, Bush R, Castle D, Cohen M, Harvey C, Galletly C. People living with psychotic illness 2010. Report on the second Australian national survey. 2011.

Mundt J, Marks I, Shear K, Greist J. The work and social adjustment scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–4.

National Mental Health Commission. A contributing life: the 2013 national report card on mental health and suicide prevention. Sydney: National Mental Health Commission; 2013.

Neil ST, Kilbride M, Pitt L, Nothard S, Welford M, Sellwood W, Morrison AP. The questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR): A measurement tool developed in collaboration with service users. Psychosis. 2009;1(2):145–55.

Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, Gold JM. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):203–13.

Norrby E, Linddahl I. Reliability of the instrument DOA: dialogue about ability related to work. Works. 2006;26(2):131–9.

Reichenberg A, Harvey P. Neuropsychological impairments in schizophrenia: Integration of performance-based and brain imaging findings. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:833–58.

Richardson JR, Peacock SJ, Hawthorne G, Iezzi A, Elsworth G, Day NA. Construction of the descriptive system for the assessment of quality of life AQoL-6D utility instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10(1):38.

Rodríguez Pulido F, Caballero Estebaranz N, González Dávila E, Melián Cartaya MJ. Cognitive remediation to improve the vocational outcomes of people with severe mental illness. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2019;31(3):1–23.

Spreen O, Strauss E. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press ; 1991.

White T, Stern RA. Neuropsychological assessment battery: psychometric and technical manual. Lutz, Fla: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 2003.

Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, Stewart-Brown S. The Warwick–Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):63.

US Army. Army individual test battery: manual of directions and scoring. Virginia: US War Department; 1944.

Van Duin D, De Winter L, Oud M, Kroon H, Veling W, Van Weeghel J. The effect of rehabilitation combined with cognitive remediation on functioning in persons with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(9):1414–25.

VIA. The VIA survey. 2018. https://www.viacharacter.org/www/Character-Strengths-Survey. Accessed 26 Mar 2021.

Wechsler D. Wechsler memory scale (WMS-III), vol. 14. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1997.

World Health Organisation. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J, Bray P, Reeder C, Williams C, Corner J. Effects on the brain of a psychological treatment: cognitive remediation therapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:144–52.

Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobor P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):472–85.

Yamaguchi S, Sato S, Horio N, Yoshida K, Shimodaira M, Taneda A, Ikebuchi E, Nisho M, Ito J. Cost-effectiveness of cognitive remediation and supported employment for people with mental illness: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2017;47(1):53–65.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Fife Employment Access Trust for their ongoing partnership and collaboration.

Funding

This work was funded by The Ian Potter Foundation, Gandel Philanthropy, Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation, Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, National Disability Insurance Agency and the WISE Employment Community Investment Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miles, A., Crosse, C., Jenkins, Z. et al. Improving Cognitive Skills for People with Mental Illness to Increase Vocational and Psychosocial Outcomes: The Employ Your Mind Program. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 8, 287–297 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-021-00225-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40737-021-00225-9