Abstract

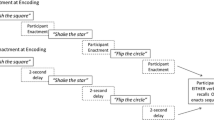

Declarative and procedural knowledge are important behaviors to teach when training staff. This study examined the training of staff declarative and procedural knowledge about a representative staff task—the Assessment of Basic Learning Abilities (ABLA), a behavioral assessment that measures an individual’s ability to learn an imitation and five two-choice discrimination skills. The ABLA was taught to 12 senior tutors of a behavioral intervention program for children with autism. The training intervention involved the senior tutors passing mastery-based unit tests and watching instructional videos related to the ABLA. The two training components were delivered by computer-aided personalized system of instruction (CAPSI). A multiple baseline design across two training sequences (see Martin & Pear, 2019, pp. 46–49), with a reversed order of the two components, was used to monitor the changes of the senior tutors’ performance on declarative and procedural knowledge. The results indicated that all senior tutors gained both types of knowledge substantially. In addition, differential contributions of the components to training effects were observed, i.e., passing unit tests was more effective in developing declarative knowledge while watching videos was more effective in developing procedural knowledge. It is recommended that when training staff efforts be made to teach both types of knowledge—because they represent different behavioral repertoires—as opposed to assuming that it is sufficient to teach only one of these repertoires.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Belisle, J., Rowsey, K. E., & Dixon, M. R. (2016). The use of in situ behavioral skills training to improve staff implementation of the PEAK relational training system. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 36(1), 71–79.

DeWiele, L. A., & Martin, G. L. (1998). The Kerr-Meyerson assessment of basic learning abilities: A self-instructional manual. Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

DeWiele, L. A., Martin, G. L., & Garinger, J. (2000). Field testing a self-instructional manual for the ABLA test. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 7(2), 93–108.

DeWiele, L., Martin, G., Martin, T., Yu, C.T., & Thomson, K. (2010). The Kerr-Meyerson assessment of basic learning abilities revised: A self-instructional manual (2nd ed.). Winnipeg, Canada: St. Amant Research Center. Retrieved July 19, 2019, from http://stamantresearch.ca/abla/

Hu, L. (2017). Training tutors and parents in China to implement preference assessment procedures and discrete trials teaching. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

Hu, L., & Pear, J. J. (2016). Effects of a self-instructional manual, computer-aided personalized system of instruction, and demonstration videos on declarative and procedural knowledge acquisition of the assessment of basic learning abilities. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 22(2), 64–79.

Hu, L., Pear, J. J., & Yu, C. T. (2012). Teaching university students knowledge and implementation of the assessment of basic learning abilities. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 18(1), 12–19.

Keller, F. S. (1968). Good-bye, teacher. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1(1), 79–89.

Kerr, N., Meyerson, L., & Flora, J. A. (1977). The measurement of motor, visual, and auditory discrimination skills. Rehabilitation Psychology, 24(Monograph Issue), 95–112.

Kinsner, W., & Pear, J. J. (1988). Computer-aided personalized system of instruction for the virtual classroom. Canadian Journal of Educational Communication, 17(1), 21–36.

Martin, G. L., & Pear, J. J. (2019). Behavior modification: What it is and how to do it (11th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Martin, G. L., & Yu, C. T. (2000). Overview on research of the assessment of basic learning abilities test. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 7(2), 10–36.

Martin, G. L., Thorsteinsson, J. R., Yu, C. T., Martin, T., & Vause, T. (2008). The assessment of basic learning abilities test for predicting learning of persons with intellectual disabilities: A review. Behavior Modification, 32(2), 228–247.

Martin, G., Martin, T., Yu, D., Thomson, K., & DeWiele, L. (2011). The ABLA-R Tester Evaluation Form. Retrieved July 19, 2019, from https://stamant.ca/research/abla/.

Miltenberger, R. G. (2016). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures (6th ed.). Boston: Cengage Learning.

Moore, J. W., & Fisher, W. W. (2007). The effects of videotape modeling on staff acquisition of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 40(1), 197–202.

Oliveira, M., Goyos, C., & Pear, J. J. (2013). A pilot investigation comparing instructional packages for MTS training: “Manual alone” vs. “manual-plus-computer-aided personalized system of instruction.”. Behavior Analyst Today, 13(3), 20–26.

Parsons, M. B., Rollyson, J. H., & Reid, D. H. (2012). Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5(2), 2–11.

Pear, J. J. (2003). Enhanced feedback using computer-aided personalized system of instruction. In W. Buskist, V. Hevern, B. K. Saville, & T. Zinn (Eds.), Essays from e-xcellence in teaching (vol. 3, ch. 11). Washington, DC: APA Division 2, Society for the Teaching of Psychology.

Pear, J. J., & Crone-Todd, D. E. (1999). Personalized system of instruction in cyberspace. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 32(2), 205–209.

Pear, J. J., & Crone-Todd, D. E. (2002). A social constructivist approach to computer-mediated instruction. Computers & Education, 38(1–3), 221–231.

Pear, J. J., & Kinsner, W. (1988). Computer-aided personalized system of instruction: An effective economical method for short- and long-distance education. Machine-Mediated Learning, 2(3), 213–237.

Pear, J. J., & Martin, T. L. (2004). Making the most of PSI with computer technology. In D. J. Moran & R. W. Malott (Eds.), Evidence-based educational methods (pp. 223–243). San Diego, CA: Elsevier & Academic Press.

Pear, J. J., & Novak, M. (1996). Computer-aided personalized system of instruction: A program evaluation. Teaching of Psychology, 23(2), 119–123.

Pear, J. J., Schnerch, G. J., Silva, K. M., Svenningsen, L., & Lambert, J. (2011). Web-based computer-aided personalized system of instruction. In W. Buskist & J. E. Groccia (Eds.), New directions for teaching and learning, Evidence-based teaching (Vol. 128, pp. 85–94). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Perry, E. H., & Pilati, M. L. (2011). Online Learning. In W. Buskist & J. E. Groccia (Eds.), New directions for teaching and learning, Evidence-based teaching (Vol. 128, pp. 95–104). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rosales, R., Stones, K., & Rehfeldt, R. A. (2009). The effects of behavioral skills training on implementation of the picture exchange communication system. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 42(3), 541–549.

Roscoe, E., Fisher, W. W., Glover, A. C., & Volkert, V. M. (2006). Evaluating the relative effects and contingent money for staff training of stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39(1), 63–77.

Sarokoff, R. A., & Sturmey, P. (2004). The effects of behavioral skills training on staff implementation of discrete-trial teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37(4), 535–538.

Sternberg, R. J. (1998). Abilities are forms of developing expertise. Educational Researcher, 27(3), 11–20.

Svenningsen, L., Bottomley, S., & Pear, J. J. (2018). Personalized learning and online instruction. In R. Zheng (Ed.), Digital technologies and instructional design for personalized learning (pp. 164–190). Hershey: IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-3940-7.

Ward-Horner, J., & Sturmey, P. (2012). Component analysis of behavior skills training in functional analysis. Behavioral Interventions, 27(2), 75–92.

Zaragoza Scherman, A., Thomson, K., Boris, A., Dodson, L., Pear, J. J., & Martin, G. (2015). Online training of discrete-trials teaching for educating children with autism spectrum disorders: A preliminary study. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 21(1), 22–34.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants involved in this study and St.Amant for their support. This research was supported in part by grant KAL 114098 from the Knowledge Translation Branch of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Parts of this manuscript were previously presented at the 40th annual conference of the Association for Behavior Analysis International in Chicago, IL, May 2014.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the University of Manitoba’s Research Ethics Board (#P2013:024) and St.Amant’s Research Access Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

The participation in the study was completely voluntary and an informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

The Description of the Contents of Six ABLA-R Videos

Video 1 (File name: ABLA L1.wmv; Length: 7 min 50 s; Level 1: Imitation): A female tester demonstrates the materials required for level 1 (i.e., imitation), viz. a yellow can, a red box, and a beige piece of foam. Then, she administrates this level to a confederate (i.e., simulated client) who plays the role of a “client,” In particular, the tester presents procedures for conducting an initial (or a three-step) prompting sequence (consisting of a demonstration, a guided trial, and a choice for an independent response), models two examples (independent trials) in which the confederate makes correct responses (i.e., drop the beige piece of foam in the box), then models several examples in which the confederate makes incorrect responses followed by an error correction procedure, instructs how to record data in response to the two correct responses, and finally demonstrates some common errors.

Video 2 (File name: ABLA L2.wmv; Length: 6 min 22 s; Level 2: Position Discrimination): The tester demonstrates procedures for conducting the initial prompting sequence using two examples of trials in which she uses different levels of prompts in guiding the confederate to engage in a correct response (i.e., dropping a foam into a yellow can on the left side of the tester). Because the confederate makes a correct response without prompting, the tester demonstrates how to implement independent trials, how to record correct and incorrect responses for the trials on a data sheet, and how to apply different prompting methods during error correction procedures followed by the incorrect responses. Finally, the tester demonstrates some common errors (e.g., accidentally providing a prompt for a correct response and forgetting to provide a reinforcer to the confederate).

Video 3 (File name: ABLA L3.wmv; Length: 3 min 26 s; Level 3: Visual discrimination): The tester illustrates the difference between Levels 2 and 3. They are similar; however, the positions of the containers are fixed in level 2 whereas they are alternated in level 3. Then, the tester demonstrates how to conduct a trial at level 3 and points out the most common errors (e.g., forgetting to switch the containers at the beginning of a trial). Finally, the tester demonstrates conducting five independent trials and recording the results on a data sheet.

Video 4 (File name: ABLA L4.wmv; Length: 5 min 24 s; Level 4: Visual matching-to-sample discrimination): The tester demonstrates the materials required for this level, viz. a yellow can, a yellow cylinder, a red box with black stripes, a red cube with black stripes, and a beige piece of foam. Then, she presents procedures for conducting the initial prompting sequence using two demonstration trials (one with the box and one with the can) in which the confederate makes correct responses (i.e., the cylinder is placed into the can and a cube is placed into the box). After that, the tester demonstrates two independent trials consisting of an example of a correct response and an example of an incorrect response followed by an error correction procedure. She then describes some common errors. Finally, she implements five trials at level 4 and instructs how to record the responses on a data sheet.

Video 5 (File name: ABLA L5.wmv; Length: 5 min 18 s; Level 5: Visual nonidentity match-to-sample discrimination): The tester demonstrates the materials required for this level, viz. a yellow can, a purple piece of wood that spells “Can,” a red box with black stripes, and a silver piece of wood that spells “BOX.” Then she presents procedures for conducting the initial prompting sequence using two demonstration trials (one with the piece of wood that spells “Can” and one with the one that spells “BOX”) in which the confederate is responded correctly by placing “Can” into the can and “BOX” into a box. After that, the tester demonstrates two independent trials consisting of an example of a correct response and an example of an incorrect response followed by an error correction procedure. Finally, she describes some common errors.

Video 6 (File name: ABLA L6.wmv; length: 6 min 26 s; Level 6: Auditory-visual combined discrimination): The tester demonstrates procedures for conducting the initial prompting sequence using two trials (one with the box and one with the can). Then, she demonstrates an example of a correct response in which the confederate followed the verbal instruction (i.e., “REDBOX” in a rapid and high tone vs. “yellow can” in a slow and low tone) to drop a beige piece of foam into a red box with black stripes. In addition, she also demonstrates an example of an incorrect response followed with an error correction procedure. Next, she describes common errors. Finally, she implements five independent trials at level 6 and instructs how to record the responses on a data sheet.

Appendix 2

Training Evaluation Survey

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, L., Wirth, K.M., Harris, R. et al. The Evaluation of Declarative and Procedural Training Components to Teach the Assessment of Basic Learning Abilities to Senior Tutors. Psychol Rec 70, 163–173 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-019-00359-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-019-00359-0